It was late Tuesday evening, Aug. 6, 1991. The place: Moscow. Change was sweeping over the Soviet Union at a dizzying pace. The old guard Communists’ failed coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, a final attempt to turn back the clock and save the USSR, was still a few weeks off, and while the empire’s demise was in sight, there was no way of telling how it would all end.

Four rabbis—Yosef Aharonov, Shlomo Cunin, Yitzchak Kogan and Sholom Ber Levine—had been sent to Moscow by the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, to bring the library of his predecessor, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, unlawfully being held by the Soviet government, back to its rightful place: the Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad-Lubavitch in Brooklyn, N.Y.

In the course of the rabbis’ work they had made a contact within the Ukrainian arm of the KGB, the Soviet secret police, who had just informed them that the KGB desired to present Lubavitch with the 1939 Stalin-era arrest files of the Rebbe’s father, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson. Hearing this, Levine and the Russian-speaking Kogan immediately boarded an overnight train to Kiev, arriving in the capital of what was still the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic at 11 a.m. on Aug. 7 and headed straight to KGB headquarters in Kiev.

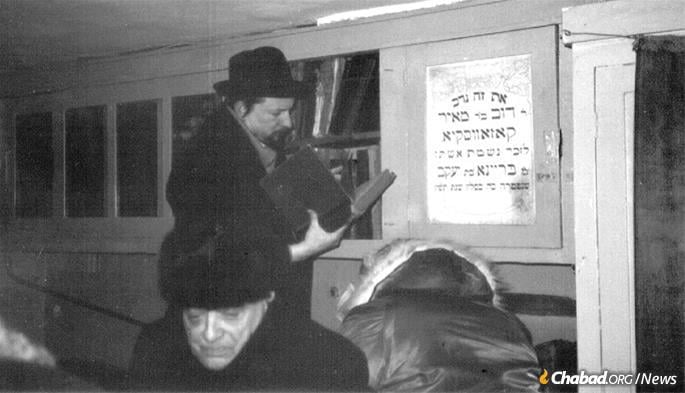

“They greeted us nicely,” Levine, chief librarian of the central Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad, records in his diary, “but were surprised that we did not want to wait for publicity.” The KGB, on the other hand, did, and asked for time to properly record the historic event. They had held the files for half a century; what was another week? Kogan, a former Refusenik who had finally been given permission to emigrate in 1986 only to be sent back as an emissary a few years later by the Rebbe, pushed back. That August day corresponded to the 27th of the Hebrew month of Av, and Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s yahrtzeit, or anniversary of death, is on the 20th of Av. “We want to receive the files within the week of the anniversary of passing of the subject of these files,” Kogan told them. The KGB asked the rabbis to return at 3 p.m., when they would have their reply.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak had been the high-profile chief rabbi of Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine, from before the 1917 October Revolution, when the city was still known as Yekaterinoslav and, after the Sixth Rebbe’s exile from Russia in 1927, the leading rabbinical figure in the Soviet Union, right up to that evening in March of 1939 when he was arrested by the NKVD, the KGB’s Stalin-era predecessor. After 10 months of brutal interrogations in secret police prisons he was sentenced to five years of exile in the remote, mosquito- and disease-infested village of Chi’ili, Kazakhstan, where it was cold and damp in the winter and stiflingly hot in the summer, and where the mud was always wet and never dried up. Silencing his fearless leadership was an important step for the Soviets in crushing religious resistance, and they went about it brutally. Yet as eyewitnesses recalled and the files attested to, despite the excruciating toll on his body from which he never recovered, his spirit never broke.

When Levine and Kogan returned, their meeting was joined by a vice chairman of Ukraine’s KGB—and a journalist with the official Tass news agency.

The senior KGB man told the rabbis that Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s arrest and subsequent treatment was wrong and should have never happened, and emphasized that it had been the sin of their predecessors, and not their own. To somehow rectify these misdeeds and offer some measure of closure and exculpation for the Jewish people, the KGB considered it appropriate to return the arrest files of this historic figure.

There were 65 pages in that initial file, the vast majority originals. It included a photograph of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak; letters of appeal written by his wife, the Rebbe’s mother, Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson; and the signed and sealed decision to exile the rabbi without trial. Levine and Kogan accepted the files on behalf of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement and caught the first plane back to Moscow.

Tass issued a detailed report—and word traveled around the world.

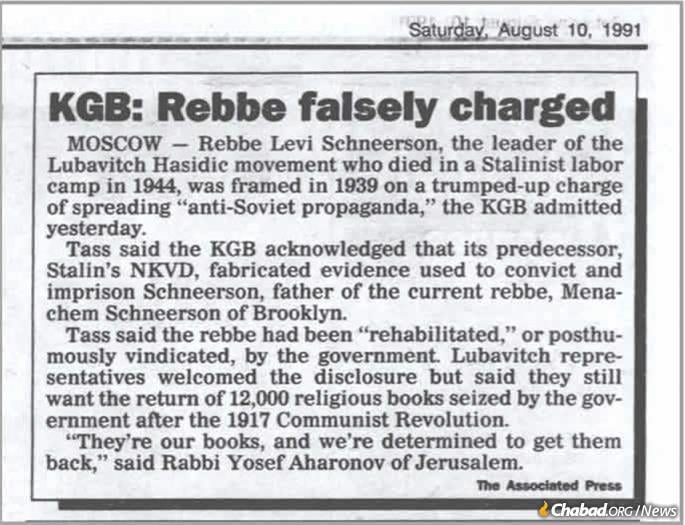

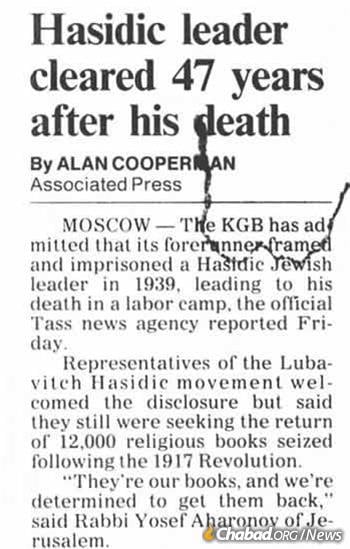

“The KGB has admitted that its forerunner framed and imprisoned a Hasidic Jewish leader in 1939, leading to his death … ,” reported the Associated Press from Moscow on Aug. 9.

“Tass said the Ukrainian branch of the security police handed over documents this week to the Lubavitch movement about the persecution of Rebbe Levi Y. Schneerson … [The rabbi] had been ‘rehabilitated,’ or posthumously vindicated by the government. The documents, including minutes of the interrogation, show that Schneerson was ‘framed up … by Stalin’s secret police,’ the state news agency said.”

Alan Cooperman, today director of religion research at the Pew Research Center, was a journalist stationed in Moscow during the fast-moving times of 1990-96 and authored the AP story. “Dramatic change was taking place in the Soviet Union at the time on a monthly, weekly and daily basis,” Cooperman explains. “There was this narrow window when this could take place; it couldn’t have happened a few years earlier, and it couldn’t have happened a few years later.”

What precisely drove the Soviet decision—whether it was an olive branch towards religion, an overture to Jews at large, an honest reckoning with its dark past or some mixture of them all—is impossible to know. What is certain, says Cooperman, is that “this was not a decision made by an archivist or a junior culture minister. This kind of a decision had to have been made at the highest levels of government, or right up next to it … ”

A few days later, on a Tuesday morning, Aharonov and Cunin flew to New York to bring the files to the subject’s son, the Rebbe.

The Rav

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson was born in White Russia on April 21, 1878 (18 Nissan, 5638) to Rabbi Baruch Schneur and Rebbetzin Zelda Rachel Schneerson. A direct descendent of the third Chabad Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch, known as the Tzemach Tzedek (1789-1866), in 1900, he married Chana, the daughter of the rabbi of Nikolayev, Ukraine, Rabbi Meir Shlomo and Rebbetzin Rachel Yanovsky. The young couple settled in Nikolayev, where their three sons—Menachem Mendel, Dovber and Yisrael Aryeh Leib—were born.

An extraordinary scholar of Talmud, Jewish law and Kabbalah who was widely consulted for his halachic opinion, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak received rabbinic ordination from Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk, Rabbi Eliyahu Chaim Meisel of Lodz, and others. In 1908 he was appointed rabbi in the city of Yekaterinoslav. According to Jewish Educational Media’s (JEM) meticulously researched 2016 biography of the Rebbe’s Early Years, there had initially been some powerful local opposition to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s appointment. Over time, however, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was able to build bridges with those who had opposed him, becoming a universally beloved figure for the entire community, upon whose lives he left a lasting imprint.

“I would spend hours in [Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s] home and I was enthralled … ,” recalled Yekaterinoslav native Avraham Shlonsky. “This was my ‘childhood study’; the world of my early years.” Shlonsky, who later became a renowned Israeli poet, never lost that childhood bond. “It still expresses itself to this day, in my inner struggle, in my soul’s unease.”

During the First World War, as thousands of Jewish refugees streaming from the Russian Empire’s borderlands reached Yekaterinoslav, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak mobilized his entire community.

“The home of the Yekaterinoslaver Rav, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, was the point of respite for the suffering Jews of Poland, Lithuania and the Baltic States … ” wrote one eyewitness, the journalist Aharon Friedenthal. “During those stormy days, the rabbi’s residence gave off the impression of a beehive. Jews were continuously streaming in and out. Some were searching for help and support, for bread and clothing for their families, while others came looking for medicine and help for sick and exhausted refugees. Still others sought legal assistance for arrested family members—fathers, brothers, uncles … The rabbi and rebbetzin, during those horrible days, knew nothing of their own lives. Everything was committed, dedicated to the rescue effort.”

Following the Bolshevik seizure of power, the 1920s saw the decimation of organized Jewish life throughout the Soviet Union. Especially ruthless and effective in this battle against religion was the Yevsektzia, the Jewish sections of the Communist Party, which wielded immense power, using it to confiscate synagogues and other communal property; force Jewish parents to send their children to new Soviet schools; and harass and intimidate rabbis and Jewish communal leaders into submission.

But Rabbi Levi Yitzchak never did get intimidated. Against all odds—and long after the rabbis of most large Soviet cities had either left their positions or curtailed their activities—he pressed on. Following the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s 1927 arrest and subsequent exile from the Soviet Union, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak became the leading rabbinical figure in the Soviet Union. He urged colleagues across the country to remain steadfast. In the early 1930s he led the Ukrainian rabbis’ refusal to sign pro-Soviet statements. From the pulpit, he called on his community members to keep their dedication to the Torah and its mitzvot. He collected funds to support the families of Jewish prisoners, ran a network of underground Jewish schools and oversaw the distribution of matzah he received from abroad. In 1936, he was involved with the construction of an “illegal” mikvah, and in the run-up to his own arrest, having refused to rubber stamp his kosher certification on matzah baked by the government, forced them to follow his stringent kosher standards.

In all this, he was undaunted and even brazen. Before one Passover holiday he gained a meeting with Mikhail Kalinin, the chairman of the presidium of the Supreme Soviet, who granted the rabbi permission to bake matzah how he saw fit for Passover use.

Authorities did not take kindly to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s insubordination. On March 28, 1939, just days before Passover, the NKVD arrested the venerable rabbi. Over the next 10 months, the 61-year-old rabbi was shuttled between secret police prisons in Dnepropetrovsk, Kiev, back to Dnepropetrovsk, then to Kharkov and on to Alma-Ata, Soviet Kazakhstan—five prisons in all. He was beaten and deprived of sleep. Some of his interrogations lasted 15 or 16 hours, followed by a break of two or three hours before starting again. He was charged with being an imperialist spy, funneling money from abroad and conducting anti-Soviet provocations at home.

Early on the morning of Hoshana Rabbah, Oct. 4, 1939, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was sentenced to five years of internal exile in the remote village of Chi’ili, Kazakhstan, where he and Rebbetzin Chana would spend the next four years.

Even after his arrest and exile his stature cast a long shadow. When the Kremlin, wishing to appease its World War II allies, sought to appoint a chief rabbi of Moscow, they briefly considered Rabbi Levi Yitzchak precisely because he was a man who would be recognized and respected abroad and at home. As Emmanuel Mikhlin, the son-in-law of the man who ultimately received the job, records in his memoirs, the government couldn’t get itself to do it: “They could not give it to a Schneerson.”

‘People Were Afraid’

Luba Liberov, 92, was born in Kharkov in 1927. As the Nazis approached the city in the fall of 1941, her family was evacuated east, making their way finally to the city of Alma-Ata (today Almaty), Kazakhstan. There her father, Betzalel Shailzon, became known for his kindness and generosity towards fellow Jewish wartime refugees.

“My father was a very good man and very religious,” she recalls at her home in Brooklyn. “But he was a misnagid. It was my uncle, Hirsh Rabinovitch, who was the Chabadnik. I remember them arguing, ‘Ay, you Chassid!’ ‘Ay, you misnagid!’ ”

As Rebbetzin Chana describes in her memoirs, Hirsh Rabinovitch and his brother, Mendel, were constant sources of help throughout her and her husband’s difficult years in Chi’ili. Mendel, upon release from the Red Army, traveled first to Chi’ili to check on Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and Rebbetzin Chana, and only afterwards did he go home to see his wife and newborn baby. Among other things, the brothers were instrumental in arranging the bribes needed to convince the authorities to allow Rabbi Levi Yitzchak to finally relocate from Chi’ili to Alma-Ata.

The year of imprisonment, interrogations and beatings, followed by the years in Chi’ili, had taken a terrible toll on Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s health. He was physically broken, the illness that would take his life in a few months already ravaging his body. Years later, when the Rebbe saw a picture of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak from this period, he could hardly recognize him. “My father, of blessed memory?” he wrote on the back of the photo. Despite it all, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak remained a towering and undaunted spiritual figure.

Just after Passover of 1944, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and Rebbetzin Chana quietly left Chi’ili and traveled to Alma-Ata. The welcome event was held in Betzalel Shailzon’s home.

“This was a big thing, because you don’t understand, people were afraid of welcoming a Schneerson,” Liberov says. “My father had a wife, three children; it could have been straight to Siberia, but he wasn’t afraid to go and greet the Rebbe, and bring him to his home.”

Liberov says her memory of the events is clouded in part because of the aura of secrecy that surrounded everything in those days.

“There was a saying in Yiddish that my parents would repeat, men tor nit (‘you shouldn’t’),” she says. “That means on the street you don’t repeat anything from the house. It was ‘beaten’ into our heads, so anything like this, it was ‘men tor nit.’ ”

But Rabbi Levi Yitzchak left an impression. “He was a different type of person.”

Liberov vividly recalls a tumult in her home when Rabbi Levi Yitzchak became particularly ill, her father, uncle and brother rushing about to bring a doctor, and her mother knitting something for the great rabbi. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak passed away on the 20th of Av, 5704, or Aug. 9, 1944. He was 66 years old. As a token of her appreciation for what they had done for her and her husband, Rebbetzin Chana gifted Liberov’s brother with Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s kiddush cup, and his gartel, a silk belt used by Chassidim during prayer.

‘Redeeming a Captive’

File in hand, Aharonov and Cunin arrived in New York the same day they left Moscow, Aug. 13, 1991, and headed straight to the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn. That night after evening prayers, the two rabbis positioned themselves in the foyer outside the Rebbe’s office at 770 Eastern Parkway, hoping to hand the files directly to the Rebbe. Instead, the Rebbe swiftly entered his office, and a minute later his secretary asked the two to come in. This was highly unusual because the Rebbe had stopped granting private audiences nearly 10 years earlier.

The Rebbe was standing in the middle of his study when they presented the file to him. Then the Rebbe spent a few minutes silently leafing through the contents.

The last time the Rebbe had seen his father was 1927, shortly before the Rebbe left the Soviet Union for the last time, but his attachment and love for his father never waned. The Rebbe often spoke publicly of his father’s self-sacrifice in the Soviet Union and the role the NKVD’s treatment of him had played in ending his life early.

“We could see the Rebbe looking at his father’s photo, turning through a few pages, then going back to the photo,” recalls Aharonov, the chairman of Tzeirei Agudat Chabad, the umbrella organization for Chabad outreach activity in Israel. “Throughout the audience, the Rebbe kept glancing through the file.”

The Rebbe thanked them and spoke about the mitzvah of pidyon shvuyim, or “redeeming a captive,” a commandment which the Rebbe applied also to holy Jewish books and items of historic value to the Jewish people. The discussion turned to the matter of the Lubavitch library held by the Soviet government and lasted for about 10 minutes. The next morning, the pair flew back to Moscow.

In terms of archival material relating to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, this would only be the beginning. Just as this initial file was being handed over from Kiev, Rabbi Zeev Vagner, editor of the Encyclopedia of Russian Jewry, was sifting through KGB archives in Dnepropetrovsk. In the spring of 1992, two representatives of the Dnepropetrovsk SBU—as the Ukrainian KGB was renamed in newly independent Ukraine—flew to Israel and presented the Chabad-affiliated Shamir Organization with three more thick files containing interrogations and other records. They also sent a formal apology to the Rebbe in New York.

One undoubtable vindication of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak is the current state of Jewish life in the city he led for 30 years. Today, after yet more political change, Dnepropetrovsk is called Dnipro, and is home to a vibrant Jewish life, including the Menorah Center, the largest Jewish center in the world.

Standing on Menorah Center’s 18th-floor viewing deck during a visit to the city a few years ago, Rabbi Shmuel Kaminezki, Dnipro’s Chabad emissary and chief rabbi since 1990, pointed out the clearly visible KGB building where Rabbi Levi Yitzchak had been imprisoned and where so many of his interrogations had taken place. One building was gray and morbid, the other gleaming and ascendant—a glass flame of Jewish life and learning casting a glow onto the city below.

Join the Discussion