This article covers the life and rabbinic leadership of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson in Yekaterinoslav-Dnipropetrovsk during the first decade of the Bolshevik regime. On his early life and leadership during the Czarist era, see The Life and Writings of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson—Part One.

An Era of Darkness Unfolds

As the second decade of the twentieth century came to a close, World War I had finally come to an end, and Europe seemed to be heading into a new era of peace and rejuvenation. Russia, however, was spiraling deeper into humanitarian and economic crisis. Having signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers in 1918, the forces of the Red Army were gradually consolidating power. Despite bitter opposition from the White Army and other anti-communist forces, they gradually drew the suffocating folds of Bolshevism across the former Czarist empire.

Ukraine and Southern Russia saw some of the heaviest and most prolonged fighting between the Whites, the Reds and other military factions. Throughout this difficult period of strife, danger and uncertainty, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson continued to lead the Jewish community of Yekaterinoslav. At the end of 1919, Bolshevik forces finally gained permanent control of the city. Rostov on the Don, where Rabbi Shalom DovBer Schneersohn of Lubavitch had been living since the winter of 1915, was conquered a few months later.1

Most Jews were not initially alarmed by the Bolshevik victories. While the Whites were notoriously anti-Semitic, the Reds preached equality for all peoples. But it soon became clear that they were fiercely anti-religious. They ridiculed traditional Jewish learning and life as backward relics of the Middle Ages, and it was their firm intention to utterly uproot it.2

While the czars had never been great friends of the Jewish people, they had never pursued systematic policies to destroy the central institutions of Jewish life. If anything, things had slowly been moving in a positive direction, with R. Shalom DovBer and his allies building ever-closer ties with governmental officials.3 But the designated “Jewish branch” of the Communist Party, the Yevsektsiya, was determined to destroy the religious heart of Jewish society.

As this new threat was looming over the Jewish people, R. Shalom DovBer’s health rapidly deteriorated. On 2 Nissan (21 March) 1920 he passed away, leaving the community to confront an existential threat without his clearheaded foresight and fearless leadership.4

Thirty years later, Rebbetzin Chana, R. Levi Yitzchak’s wife, recalled that dark day in her memoir:

I remember when the news arrived. At the time, contact by mail and railway was very poor. Yet we came to know of it that same day.

I have no words to describe the impression that this news made. It felt as if our whole life had stopped. That’s how it was in our home, and among those who were close to us, particularly among those who were Chabad chassidim. My husband, of blessed memory, wept aloud, something he almost never did.

As soon as those I mentioned found out, I don’t remember how, they came directly to us in our home. More than twenty people came to our home and sat shivah, our spirit utterly crushed. We cried so very much.5

Reorganization and Resilience

The next few years were particularly desperate. Large swaths of Russia were gripped by famine and disease, and Chabad chassidim were scattered and disoriented. But R. Shalom DovBer’s son and successor, R. Yosef Yitzchak, had the fortitude to rise above his personal tragedy, raising funds and rallying the chassidim to reorganize and rebuild.

In a letter penned the following summer, R. Yosef Yitzchak wrote:

No one person can take on such a project without the help of beloved friends, each in their place . . . rallying the chassidim, and drawing people closer to service of G‑d. . . . It occurred to me to divide the country into sections. . . . I settled one of our students in Moscow . . . another in Chernigov . . . my friend (the addressee) is in Kharkov . . . and my relative Reb Leivik is in Yekaterinoslav. All of us together will work to make Torah study groups. . . . People will study and be inspired to actual service of G‑d . . . not sitting with folded arms . . .6

By this time the Communist crackdown on religion had began in earnest, and in addition to his work on a local level, R. Levi Yitzchak was called upon to help orchestrate a general protest. After the Yevsektsiya threatened to close the Tomchei Temimim yeshivah, whose main center was then located in Rostov, R. Yosef Yitzchak’s son-in-law, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gourary, wrote to R. Levi Yitzchak:

As they plotted, so they acted. They planted a sword in the study hall and said, “Anyone who enters will be run through!” Although they have not yet been able to actually expel the students and send them for hard labor . . . if we sit idle, with folded arms, only G‑d knows how it will end . . .

The first action advised . . . is to organize a protest of all craftsmen independently and all workers independently, who will sign a protest. . . . The protest should read something like this: Since we heard that the Yevsektsiya in Rostov wants to shut down the yeshivah, we craftsmen and workers who need the services of rabbis, shochatim (kosher slaughterers), mohalim (ritual circumcisers), etc. etc., object to this with all our might, and request that the yeshivah be maintained as it has been until now . . .

Two notarized copies should be sent, one here (to Rostov) . . . one to Moscow through our emissary . . .7

If R. Levi Yitzchak successfully organized such a protest, it made little impact on the authorities. A sham trial was held, R. Shmaryahu was jailed for several days, all of R. Yosef Yitzchak’s possessions were confiscated, and the yeshivah was closed.8 From this point on, the students of Yeshivah Tomchei Temimim Lubavitch were forced to study underground, dispersing and opening clandestine branches of the yeshivah in towns and cities across the Soviet Union. When one branch would be discovered and shut down, the students and staff who managed to evade arrest would move to another location, either joining an existing branch or establishing a new one. With time Yekaterinoslav (or Dnipropetrovsk, as the city was renamed in 1926) would also host groups of yeshivah students, with a large contingent relocating there following the closure of the yeshivah in Nevel at the end of 1928.9

Famine and Relief

Led by an authoritative rabbinate and a philanthropic lay leadership, Yekaterinoslav’s Jewish community had previously run a wide range of religious and social institutions, including a hospital, orphanage and soup kitchen. But now the rabbis were relentlessly persecuted, the wealthy patrons had been robbed of their assets or forced to flee abroad, and the communal institutions were seized and shut down. Under these circumstances, only the synagogues and the burial society continued to function; mikvaot (ritual baths for the observance of family sanctity laws) and chadarim (traditional Jewish schools) were forced to operate secretly.10

In the summer of 1921, R. Levi Yitzchak’s colleague in the Yekaterinoslav rabbinate, Rabbi Pinchos Gelman, was struck down by cancer and passed away. All the weight of the struggling community, numbering nearly a hundred thousand souls, now fell on R. Levi Yitzchak’s shoulders.11

The summer of 1921 also saw the beginnings of a famine that devastated the entire region. According to figures compiled by the Jewish Burial Society in Yekaterinoslav, more than two thousand Jews died of starvation, typhus, cholera, consumption, spotted fever and other famine-related diseases during the course of the year. Another 3,137 deaths were recorded for the first half of 1922 alone.12

In mid-1922 several humanitarian organizations, led by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (known as “the Joint”), began pouring aid into the region, setting up medical clinics, orphanages and soup kitchens, and supplying farmers with agricultural equipment and resources.13 They managed to gain the trust of the Soviet authorities, and often provided relief to non-Jews alongside Jews.14

In the wake of these efforts the situation quickly improved, and in July 1923 the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) reported that “the mortality of Jews in Ekaterynoslav, Ukrainse (sic), has been reduced to less than one twentieth of the 1922 rate. Figures for March 1922 showed 786 deaths in Ekaterinoslav, while for March this year, only 36 deaths occurred in the Jewish population. Of the 786 deaths in March of last year, 283 were due to starvation while during the same period this year only one died there of hunger.”15

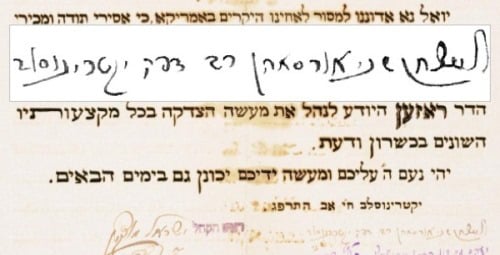

As leader of the Jewish community, R. Levi Yitzchak was deeply involved in the relief effort, and appears as the first signatory on an official certificate of thanks issued by the Yekaterinoslav Jewish community to Dr. Joseph A. Rosen of the Joint:

The Jewish community in our city . . . considers it a pleasant obligation to communicate our thanks and blessing for all your tremendous achievements for the good of wretched people; for every trouble that should not come on our poor brethren . . . the aforementioned honorable committee comes like a saving angel to rescue them; to sustain the hungry, clothe the naked, heal the sick, to provide fuel to stoke the fires on cold winter days . . .

Please make known to our precious brothers in America that we are indebted with gratitude, and recognize the good of their philanthropic spirit and their righteousness. For eternity we shall never forget their salvation and help. . . . May G‑d’s grace be upon you, and may He strengthen the work of your hands . . .16

An Invitation to Jerusalem

In the spring of 1924, R. Yosef Yitzchak received a letter from the Chabad community in Jerusalem making known their intention to appoint R. Levi Yitzchak as their rabbi, and enclosing an invitation to be forwarded to him. In response, R. Yosef Yitzchak wrote:

Your letter, together with the letter for my relative the famed rabbi and gaon R. Levi Yitzchak, arrived in order. I’m inclined to the idea, and agree that if only the honored rabbi and gaon will agree to your suggestion, you should make every possible effort to achieve this. I have fulfilled your request and sent your letter to the honored rabbi and gaon, my relative.17

This was the first of several opportunities, over the course of more than a decade, that would have given R. Levi Yitzchak a way to escape the increasing weight of Soviet oppression. Ten years later he was invited to become chief rabbi of Tel Aviv–Jaffa, and he was also asked to head a congregation in the United States, but none of these proposals came to fruition. Rebbetzin Chana later recalled that “when the topic of possibly emigrating from the Soviet Union came up, my husband always declared that he had no right to do so”:

If he would leave, he argued, there would be no more kosher meat in his region, no observance of family sanctity laws or Jewish religious practice in general. Since he couldn’t see anyone else taking responsibility for all this, how could he possibly forsake it all? Regarding immigration to the Land of Israel, his opinion was that he wasn’t at a lofty enough spiritual level to live there. “A Jew shouldn’t immigrate to the land of Israel only for the sake of his livelihood,” he would say.18

In 1939, under interrogation by the Soviet secret police, R. Levi Yitzchak gave an account of some of these episodes, acknowledging that later in life he himself initiated a request for a visa to the Holy Land, “but I never applied to receive an exit pass for any one of those visas.” When asked why he requested a visa but never applied to leave the USSR, he explained his general position regarding immigration and the specific circumstances under which he did seek to travel to the Land of Israel:

I don’t wish to travel to Palestine for arbitrary purposes; therefore I refused to travel there in 1925, 1924. Later, when I grew older, I wanted to travel there only because I am a believing Jew, and I wanted to live out the rest of my life there and be buried in the Holy Land. However the illness of my son, Berel, prevented me from traveling.19

Invitations from such prestigious communities are a sign of how well regarded R. Levi Yitzchak was even beyond the borders of Soviet Russia. But instead of exchanging his struggle for a position where he would be treated with due honor and respect, he chose to remain in increasingly dire circumstances, in order to ensure that the spark of Judaism would not be extinguished, and to remain close to his ailing son. His interrogators asked him how the Jerusalem community knew of his status and expertise though he lived so far away, and the government transcript records his simple response, “I don’t know.”20

A Powerful Persona

In the face of increasing anti-religious antagonism from the authorities, and subject to exorbitant “clerical” taxation, many rabbis felt compelled to lower their profile or even to abandon their posts.21 But R. Levi Yitzchak refused to be intimidated. He maintained the city’s religious institutions and openly encouraged his constituents to strengthen their commitment to Jewish life and learning, both personally and financially. At a time when mikvaot were being shut down, he was building new ones. He was widely known and respected throughout the city, commanding great influence even among card-carrying communists.22

Zvi Harkavy, editor of the Yekaterinoslav-Dnepropetrovsk memorial book and a grandson of Moshe Karpas (the leading opponent of R. Levi Yitzchak’s initial candidacy23 ), came of age during the early Communist period, and recalled the “powerful charisma” of R. Levi Yitzchak’s persona:

In truth, he was worthy of being a chassidic rebbe. . . . I remember him standing on the platform in the synagogue on Kazatzia Street, before the Musaf prayer on the festival of Shavuot, orating with flaming passion on the image of the Messiah.24

To openly espouse so vigorous a vision of Jewish perpetuation and triumph was dangerous enough; to raise funds on behalf of Chabad’s underground yeshivah network was even more audacious. Rabbi Meir Gurkov was a graduate of the original Tomchei Temimim yeshivah in Lubavitch, and acted as a traveling fundraiser for the network between 1925 and 1927. When he came to a town, he would discreetly make himself known to those who could be trusted, and most would not run the risk of allowing him to make a public appeal in their synagogues. When he came to Yekaterinoslav-Dnipropetrovsk, however, he received a much warmer reception:

I spent one Shabbat as a guest in the home of the Rebbe’s father, the scholarly genius, rabbi and chassid, R. Levi Yitzchak Schneerson. I prayed in his synagogue, and he greatly honored me, inviting me to speak following the reading of the Torah from up on the platform and explain the purpose of my arrival. That Shabbat I derived tremendous pleasure from his holy talk, and also from the chassidic teachings that he spoke with such fiery devotion, deep concepts explained according to Kabbalistic teachings . . .

One day he took me to tour his holy work constructing the new mikvah, which he enhanced with many new improvements, with great wisdom as befits someone as intelligent as he. It took particular intelligence to raise the requisite funds for this mikvah, which cost a hefty sum.

I remember too that after the third Shabbat meal he took me into a large hall, and there too he spoke words of Torah. The Rebbe (R. Levi Yitzchak’s son, R. Menachem Mendel, who later became the seventh rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch) was also there, and the conversation revolved around the idea that the infinite capacity of G‑d is clearly revealed even in the finite. They had an involved and intricate discussion on this topic, but I don’t remember the details.25

Rebbetzin Chana recalled that the mikvah built by R. Levi Yitzchak in the courtyard of the New Piyorovi Street synagogue continued to be used after the synagogue and mikvah were officially closed by the authorities, and even after R. Levi Yitzchak himself was arrested and exiled.26 Under interrogation following his arrest in 1939, R. Levi Yitzchak admitted that he was “guilty” of building another mikvah in the courtyard of the Kotsuvinskiya Street synagogue.

Q. “Tell the investigators about your part in building an illegal mikvah in the city of Dnipropetrovsk.”

A. “With the closure of the mikvah in 1929, several religious Jews began asking me to build an illegal mikvah. Therefore, when the administration of the Kotsuvinskiya Street synagogue agreed to have a mikvah built in the synagogue courtyard, I took part in the building without permission from the government.”

Q. “Who funded the building of the mikvah?”

A. “The synagogue administration and I collected donations from religious Jews.”

Q. “Why did you take part in the building of the mikvah without authorization from the local authorities?”

A. “I thought that mikvahs are essentially not forbidden by the Soviet government, and that this is not an anti-Soviet activity. In Moscow, for example, the mikvah was authorized by the Soviet government, and in the city of Kharkov it was never shut down. . . . With regard to building permits for the mikvah, as is required for building in general, the synagogue administration would be responsible to obtain it, not I.”

Q. “From which year to which year did the illegal mikvah function?”

A. “The mikvah building was begun approximately in August 1936, and it began to be used in February or March 1937, functioning for about four months.”27

A Secret Meeting

With the government doing everything possible to subdue the religious character of Jewish life, any amount of publicity for those actively promoting Torah study and mitzvah observance was downright dangerous. The individual who stood to lose the most was R. Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, who was then leading the struggle for survival from his base in Leningrad, the Communist capital.28 His operations were generally conducted in secrecy, but towards the end of 1926 the struggle to preserve Torah-true Judaism again became an issue of national prominence.29

In R. Yosef Yitzchak’s view, it was crucial that the Jewish lay populence look to G‑d-fearing and scholarly rabbis for communal leadership and religious inspiration. Under wavering and unlearned leaders the bar would be set ever lower, and as governmental persecution increased, general religious commitment would dissolve all the faster. R. Yosef Yitzchak was therefore doubly concerned when lay leaders of the Leningrad Jewish community sought to convene a national meeting. Aside from the unwanted attention such a meeting would draw, R. Yosef Yitzchak argued that a meeting convened by lay leaders, many of whom did not themselves live religious lives, could easily play into the hands of the Yevsektsiya. Any suggestion that Jewish law and learning was not of utmost concern would be translated into an admission that Jewish religious life was an outmoded relic better replaced by communism.30

At the same time a group of traditional rabbis, led by Rabbi Shmuel Kipnis, sought to convene a rabbinic assembly in Korosten, Ukraine, in an effort to gain governmental recognition of the religious Jewish communities and their rabbinic leadership. Before acting upon his plan, R. Kipnis traveled to Leningrad to consult with R. Yosef Yitzchak. As the de facto leader of Russian Jewry, no such meeting could legitimately take place without his consent.31

Following his arrest in 1939, R. Levi Yitzchak’s interrogators cross-examined him about his role in the deliberations surrounding these proposed meetings:

Q. “We know through our investigations that you attended and took an active part in a secret meeting of rabbis in the city of Leningrad, which occurred in 1927. Do you confirm this?”

A. “Yes, at the end of 1926 or 1927, I don’t remember precisely, I received a letter from Rabbi [Yosef Yitzchak] Schneersohn, saying that I must come to Leningrad. When I arrived in Leningrad, I stayed in Rabbi Schneersohn’s apartment. He told me that the religious community in Leningrad was considering calling a congress of Jewish communities and synagogues in order to discuss religious issues. Therefore, according to what Rabbi Schneersohn told me, he called a meeting of several reliable rabbis for a preliminary discussion as to whether this congress was necessary . . .

“At these meetings we discussed the issue of getting official recognition for the religious communities, because the Soviet government at that time forbade the official existence of a Jewish religious community in many places.”32

According to R. Levi Yitzchak’s testimony the meetings were attended by a select group of influential rabbis and lay leaders, and took place both in R. Yosef Yitzchak’s apartment and in the home of Rabbi David Tevel Katzenelenbogen, the chief rabbi of Leningrad. It is noteworthy that he was careful only to mention the names of individuals who were either no longer alive or who had safely left the country. As to the outcome of these meetings, R. Levi Yitzchak testified, “I formed the opinion that the congress should take place.” R. Yosef Yitzchak, however, “was opposed to the organization of a congress to discuss these issues.”

While some might suppose that R. Levi Yitzchak was attempting to disassociate himself from R. Yosef Yitzchak’s stance, such a reading coheres neither with his forthright character nor with the record of his interrogations. In the very first session, without even being asked, he openly admits to the “crime” of being a lifelong adherent of Chabad chassidism, and on several occasions he freely discusses his strong family ties with R. Yosef Yitzchak, whose daughter would marry his oldest son in 1928. R. Levi Yitzchak’s testimony seems to reflect a genuine difference of opinion; R. Yosef Yitzchak did not call on R. Levi Yitzchak to act as a “yes man,” but because he could be relied upon to offer independent opinion and perspective.

This also reflects R. Levi Yitzchak’s general stance vis-à-vis the Soviet authorities. He refused to run and hide, and openly confronted the authorities with his Judaism. On another occasion he publicly exhorted his constituency to declare their personal religious faith on official documentation,33 and in this case he advocated a similar stance on a communal level. R. Yosef Yitzchak’s reservations stemmed from the potential fallout of the proposed conferences. While he agreed that the effort to convince the Soviet government to officially recognize the religious communities and their leadership was a worthy cause, he correctly assumed that it would not be successful. His apprehension that these efforts would elicit even greater persecution also came to unfortunate realization.

The conference proposed by the Leningrad lay leaders never took place, but the one organized by Rabbi Kipnis was convened in October 1926. R. Levi Yitzchak and R. Yosef Yitzchak did not attend, but it never would have taken place without the latter’s consent and financial support. Many of the participants were Chabad chassidim, and R. Yosef Yitzchak was declared the honorary president in absentia. This raised the ire of the authorities, and was one of the factors that led to R. Yosef Yitzchak’s arrest in June 1927.34

A Long-Distance Celebration

Following his arrest, R. Yosef Yitzchak was initially imprisoned, then exiled, and ultimately released on condition that he leave the Soviet Union.35 Select members of his family and household were also allowed to leave alongside him, among them R. Levi Yitzchak’s oldest son, R. Menachem Mendel, who was by then the intended husband of R. Yosef Yitzchak’s second daughter, Chaya Mushka.36 It was hoped that R. Levi Yitzchak and Rebbetzin Chana would be permitted to travel to Warsaw to participate in the wedding celebration, but the authorities refused to accommodate their request.37

The enforced separation did not prevent R. Levi Yitzchak and Rebbetzin Chana from participating wholeheartedly in the celebration. “Our hearts were deeply distressed,” Rebbetzin Chana later recalled, “but we banished the anguish by rejoicing.”38

In one of several letters written to his son in the week before the wedding, which took place at the end of 1928, R. Levi Yitzchak wrote:

Do not be anxious that we, your father and your mother, are not together with you for your wedding. . . . We are with you in our hearts and souls, and no spatial distance can separate us in this regard at all. We are absolutely together, literally united.39

These were not mere words. The deep-felt joy exuded by R. Menachem Mendel’s parents swept up all their acquaintances, and the entire Jewish community of Dnipropetrovsk joined them in the exuberant wedding celebrations.

R. Levi Yitzchak’s brother, R. Shmuel, traveled to the city to participate, and vividly described the rejoicing in a letter to the newlywed couple. “The measure of the preparations and the rejoicing,” he wrote, “was truly as if you were literally here, not only in spirit but also in body.” Invitations were sent out for a wedding feast in R. Levi Yitzchak’s home, and the festivities began several days earlier, on the Shabbat preceding the special day. Many people gathered in R. Levi Yitzchak’s synagogue, and after the morning prayers a celebratory kiddush was held. With true chassidic exuberance the assembled danced, not only the floor but on the tables too. For several days an unending stream of congratulatory telegrams poured in from across Russia and beyond.40

The wedding itself was all-night affair. It began with formal speeches on the part of R. Levi Yitzchak, his brother, and several community notables. All the synagogues in the city were represented, and the Jewish community council presented two official scrolls of blessing, one addressed to R. Levi Yitzchak and the other to R. Menachem Mendel. Hundreds of Jews from all sectors of the community converged on the Schneerson home, many of them standing packed together to participate in the celebration. Following the speeches, local musicians began to play, and the exuberant dancing lasted till the morning.

For Rebbetzin Chana, the highlight of the evening was when her husband danced together with his brother R. Shmuel, and with her father, R. Meir Shlomo Yanovski. “The rabbis continued to dance for a long while,” she later wrote. “Everyone present remained standing, and couldn’t hold back their tears; this was the bittersweet sort of celebration it was.”41 R. Levi Yitzchak requested, then insisted, that R. Meir Shlomo dance with his daughter, Rebbetzin Chana, so that she too could give full expression to the pride, joy and hope with which her soul overflowed.42

The exalted atmosphere was tinged by a faint cloud of apprehension. But for a brief moment, the small space in R. Levi Yitzchak’s home had been lifted into a realm where the stifling grip of Soviet repression no longer mattered. “In the morning,” Rebbetzin Chana recalled, “everyone left to their daytime jobs. My husband’s inspiration had somehow transported them into a different world. No one wanted to consider what price they might pay for showing us such friendship and participating in the celebration. As they were about to leave, Dr. Baruch Motzkin and a lawyer who was a grandson of Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan told me that in their entire lives they had never experienced such a remarkable night, nor will they ever forget this unique celebration and my husband’s powerful spiritual energy.”43

Over the course of the next decade R. Menachem Mendel and his father carried on an extensive correspondence, delving deeply into the most esoteric aspects of Torah thought. At the same time, R. Levi Yitzchak maintained the struggle for Judaism in the face of ever-increasing constraints. But with R. Levi Yitzchak’s arrest in 1939, and the outbreak of World War II, the lines of communication between them were cut.44 Tragically, his often expressed hope that he would soon be reunited with his beloved son and daughter-in-law was not to be fulfilled. In 1947, after twenty years of separation, Rebbetzin Chana was reunited with her son in Paris.45

Join the Discussion