The commandments of the Torah are called the Torah’s body. That body is vested in garments, which are stories of this world. Fools look at the garments and know nothing more. Those who know better do not look at the garment but at the body. Wise servants of the supernal King look only at the soul, which is literally the core of the entire Torah. There is a garment, and a body, and a soul, and the soul of the soul, and all are united one with the other.

- Zohar, Volume 3, 152a1

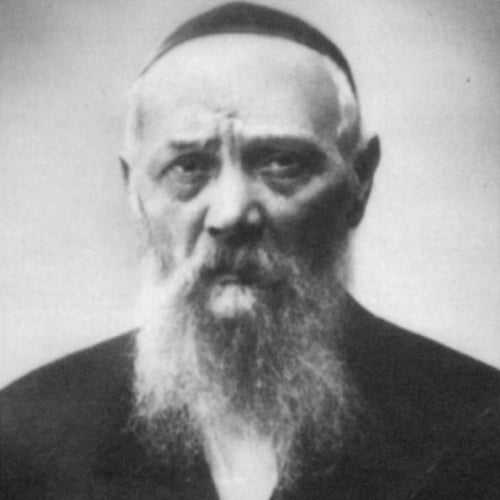

To study the writings of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, father of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, is to realize that his entire life was an extended meditation on the mysterious entanglement of body and soul. As a communal leader he was acutely sensitive to life’s daily practicalities and to the shifting political moods that would forever change the face of Judaism in Russia. As a student of the Kabbalah he would describe all of life’s events as external refractions of the cosmic soul.

His son was the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson of righteous memory, who famously built Chabad into an international presence. Through him, R. Levi Yitzchak’s ideas and actions continue to reverberate across the globe.

From Dobryanka to Nikolayev

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson was born on the 18th of Nissan, 1878 in the town of Dobryanka (also called Padobryanka), midway between the cities of Gomel in Belarus and Chernigov in Ukraine. His father was Rabbi Baruch Schneur Zalman Schneerson, a great grandson of Rabbi Menachem Mendel, the Tzemach Tzedek of Lubavitch, and his mother was Zelda Rachel Chaikin. The Chaikins were an illustrious family of Chabad chassidim. Zelda Rachel’s uncle, Rabbi Yoel Chaikin, was the Chabad rabbi of Dobryanka and the primary teacher of R. Levi Yitzchak’s youth.2

When the fifth Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch, Rabbi Shalom DovBer Schneersohn (Rashab), opened the Tomchei Temimim Yeshiva in 1897, R. Levi Yitzchak was nineteen years old.3 The Yeshiva’s establishment heralded a new golden age for the town of Lubavitch and for the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, with R. Shalom DovBer becoming one of the most influential Jewish leaders in the Russian Empire.4

Though it remains unclear whether or not R. Levi Yitzchak was enrolled as a student in the Yeshiva,5 we know from R. Shalom DovBer’s correspondence that the young man’s scholarship and ability had come to his attention, and that he personally encouraged R. Levi Yitzchak’s marriage to Rebbetzin Chana, the daughter of Rabbi Meir Shlomo Yanovski of Nikolayev, in the year 1900.6 Many years later, in a letter anticipating the wedding of his own son, the Rebbe, R. Levi Yitzchak wrote, “when you stand beneath the canopy, meditate in awe of G‑d; so the Rebbe (i.e. R. Shalom DovBer) said to me before my own marriage.”7

The young couple spent their first years together in Nikolayev. As was generally the custom in rabbinic circles at the time, R. Levi Yitzchak’s father-in-law supported him for several years so that he could continue his studies without becoming overly involved in worldly affairs. R. Meir Shlomo was an experienced communal leader and rabbinic judge, as well as a chassid of deep piety. He was a living example of the balance of erudition, dignity, human sympathy and political sensitivity that the rabbi of a large city needs to strike. R. Levi Yitzchak was free to immerse himself in scholarship, but this was also an excellent opportunity to discover the daily practicalities of rabbinic leadership.

Shortly after R. Levi Yitzchak’s marriage, R. Meir Shlomo’s fifteen year old son, Yisroel Leib, contracted typhoid fever and tragically succumbed to the disease. A 1901 letter addressed by R. Shalom DovBer offers sympathetic support and advice to R. Meir Shlomo, and tangentially reveals another aspect of his regard for R. Levi Yitzchak. To ward off the threat of depression he suggested that R. Meir Shlomo fortify his faith with a program of Torah study. Specifically, he advised him first to learn the section of R. Schneur Zalman of Liadi’s Tanya dealing with happiness and depression, and then to learn the long series of Chassidic discourses by his father, Rabbi Shmuel Schneersohn of Lubavitch (the Rebbe Maharash), known as Vekacha Hagadol. “You should learn it each day for several hours, do not leave it in the middle, but finish it with G‑d’s help. And if you will learn it with your son-in-law, my relative, the rabbi (i.e. R. Levi Yitzchak), it will be all the better.”8

These were texts that R. Meir Shlomo was already familiar with. R. Shalom DovBer was not prescribing this regime of study to fill a gap in his knowledge, but for the therapeutic value of engaging with the conflicts of heart and mind in the company of an understanding companion. R. Shalom DovBer was apparently confident that R. Levi Yitzchak possessed the understanding and strength of character to provide moral support in the face of tragedy.

The Schneerson Home

In the spring of 1902 R. Levi Yitzchak and Rebbetzin Chana welcomed their firstborn son into the world. His brit (circumcision ceremony) coincided with R. Levi Yitzchak’s 24th birthday, and he was named Menachem Mendel, after his ancestor the Tzemach Tzedek. With time he would follow in the footsteps of his namesake, becoming the seventh rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch. A second son was born in 1904, and a third in 1909. Respectively, they were named DovBer (Berel) and Yisroel Aryeh Leib (Leibel).

Shortly after Leibel’s birth the family moved to Yekaterinoslav (later renamed Dnipropetrovsk), where R. Levi Yitzchak was appointed to the rabbinate.9 There they lived next door to their relatives, the Shlonsky family. Two of the Shlonsky children, Avraham and Verdina, became well known literary figures in Israel, and their memories provide a glimpse into the atmosphere in the Schneerson home, and into R. Levi Yitzchak’s way with children.10

The two families had much in common, but there were also many differences between them. Avraham described his own father as “a man of Jewish and general culture, and at the same time a man of deep religious sentiment.” He was conversant in Chabad texts, Russian and Hebrew literature, and had a taste for classical music. His library included a wide range of holy and secular books in a variety of languages. His mother was apparently of a less religious inclination, and wanted him to attend the local high school rather than the Yeshivah in Lubavitch. She also had strong Socialist and Zionist persuasions.

These ideological differences did not inspire any personal tension. The children played freely together, mischievously climbing through the open windows of their respective homes, and as they got older they developed shared interests in chassidism, politics and the sciences. The mothers shopped together. And come the Sukkot festival, both families would pile into the Schneerson Sukkah, where they would sing both Chassidic and popular songs. The doors and windows of the Schneerson home were wide open to the world, yet it remained a bastion of chasidic piety.

In the Schneerson home, Avraham recalled, “I inhaled the existential spirit of the Chabad world... and its mark is upon me till today.”11 In her mind, Verdina said, the members of the Schneerson family carried a special aura. The Rabbi and his wife, Rebbetzin Chana were “like a king and queen—so beautiful, esthetic, musical and pure...” She was “beautiful, elegant and sociable,” he “majestic and handsome,” and their children “all beautiful and pure.”

Verdina’s childhood awe of R. Levi Yitzchak even enabled her to overcome her fear of fire. A candle is customarily lit before the havdalah ceremony at the conclusion of Shabbat. “I remember that Reb Leivik called me before the havdalah ceremony, he held me and then gave me matches, and said I should light the candle. I was afraid, but fortified by my regard for him I lit the candle successfully.”

Verdina also described Rabbi Levi Yitzchak’s study; a large room with a long table covered in a green cloth. Its walls were lined with overflowing bookcases, and many of the books were bound in leather.

Under Rabbi Shalom DovBer’s Wing

When still in his mid-twenties, several years before his appointment to a rabbinical position, R. Levi Yitzchak was already included in discussions of national importance. R. Shalom DovBer’s son and successor, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, wrote that “Beginning in 1902, R. Levi Yitzchak took part in all the meetings regarding communal matters convened by the Lubavitcher Rebbe (R. Shalom DovBer),”12 and that he “played a major role in the matzah campaign on behalf of the soldiers during the Russo-Japanese war of 1905.”13

Extant correspondence attests to his role in other initiatives led by R. Shalom DovBer, including a renewed drive to strengthen the Chabad community in the Land of Israel. In the first generation of Chabad, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi had insisted that his followers regularly contribute funds to be sent to the Holy Land.14 Ever since, strong institutional and family ties were maintained between successive Chabad rebbes and the Land of Israel, and a profound regard for its spiritual sanctity was deeply embedded in Chabad’s collective consciousness.15

By the first decade of the twentieth century R. Shalom DovBer was increasingly concerned about the rise of secular Zionism, which threatened to replace Chabad’s spiritual vision of the Holy Land with a culture of irreligious nationalism. In 1905 he formed a committee that would raise funds and implement resolutions designed to strengthen the Chabad community in Hebron as a bastion of piety and Torah study that would withstand the inroads of secularization.16 R. Shalom DovBer valued R. Levi Yitzchak’s judgment and organizational ability, appointing him to the committee and relying on him to communicate his intentions and directives to its other members.17

During R. Levi Yitzchak’s frequent trips to Lubavitch, he would not only consult with R. Shalom DovBer on communal matters, but also listened to the Chassidic discourses that the latter delivered each Friday night in the great hall of the Tomchei Temimim Yeshiva. These discourses drew heavily on Talmudic, Midrashic, Kabbalistic and philosophical sources, as well as earlier Chabad texts, and are known for their clear and systematic development of complex theosophical ideas. Several discourses from this period are cited in R. Levi Yitzchak’s writings, though all his surviving manuscripts date from several decades later. As a family member and close confidant he would likely join R. Shalom DovBer for Shabbat meals and otherwise spend time in his home.

Although few details have reached us of the early development of their relationship, we do know that R. Levi Yitzchak looked to R. Shalom DovBer not only for communal leadership and advice, but also for spiritual guidance and edification. R. Levi Yitzchak’s scholarly writings differ methodologically and stylistically from the discourses of R. Shalom DovBer, but their underlying messages are deeply resonant. R. Levi Yitzchak is often thought of as a Kabbalist, and his writings are indeed heavy with Kabbalisitic terminology, but ideologically they are imbued with the spirit of Chabad thought as preserved and taught by R. Shalom DovBer and his forefathers.18

R. Levi Yitzchak recognized R. Shalom DovBer as a master of the Jewish literary canon and as a spiritual giant, and regarded him with the special brand of allegiance and devotion that a chassid has for his rebbe. R. Shalom DovBer likewise took special pride in R. Levi Yitzchak’s rabbinic prowess, worldly competence, spiritual piety and scholarly depth. He was one of three individuals singled out by R. Shalom DovBer for special praise. “These,” he said, “are my rabbis. I will take pride in them in this world and in the next. When one of them asks a question, you must carefully consider your answer.”19

A Visit to Brisk

From 1905 and on R. Shalom DovBer actively sought a suitable rabbinic position on R. Levi Yitzchak’s behalf.20 In a 1906 letter he wrote, “I hereby request that your honor make efforts that my relative and beloved friend, the famed rabbi and chassid, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneersohn, be accepted as rabbi in your community. I truly find this to be for the good of your prestige, that you should have a rabbi such as this whom the rabbinic crown so befits, due to his great worth in Torah and awe of G‑d. He also knows and understands worldly matters, and I strongly anticipate that you will derive satisfaction from him in every respect…”21

One of the communities considering his appointment demanded that he receive a certificate of ordination from Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk, a famous Talmudic scholar and communal leader. When R. Levi Yitzchak asked R. Shalom DovBer for a letter of introduction, the latter replied that no introduction would be necessary, encouraging him to travel to Brisk in person, and expressing confidence that R. Chaim would independently approve of him. “Certainly he will draw you close, for he truly fears G‑d… if he generally bestows ordination, I trust that he will extend it to you…”22

The meeting between R. Levi Yitzchak and R. Chaim served not only to cement the former’s status as a Talmudic scholar and legal decisor, but also to underscore R. Levi Yitzchak’s intellectual immersion in Chassidic and Kabbilistic texts. R. Levi Yitzchak’s son, the Rebbe, later related that, half in jest and half in exasperation, R. Chaim exclaimed, “Gevald Reb Leivik! You have such a good head, in what have you placed it?!” As a non-chassid, R. Chaim apparently thought that R. Levi Yitzchak’s scholarly ability should have been reserved for Talmud and Jewish law alone.23

The Rebbe also related that R. Chaim presented his father with a practical legal question, which had been brought to his attention, involving both the laws of Shabbat and Sukkot. On Shabbat one cannot carry from a private home into a public courtyard unless an eruv is set up. Loosely defined, an eruv is a legal mechanism that changes the status of the public courtyard, making it an extension of your private space. On Sukkot you are required to eat in a sukkah-hut built under the open sky. Several private householders had built a shared sukkah in a public courtyard, and had forgotten to put an eruv in place to allow them to carry their food to the sukkah on Shabbat. What were they to do?

Without skipping a beat, R. Levi Yitzchak asserted that the sukkah itself was an eruv. Since the private householders intended to eat their meals there, it automatically transformed the public courtyard into an extension of their private domains. The laws of eruv are notoriously complex, and R. Chaim was impressed and gratified by R. Levi Yitzchak’s conceptual clarity, agility and innovation.24

Waves of Change

When Rabbi Dov Zev (Bere Volf) Kozevnikov, the Chabad rabbi of Yekaterinoslav, passed away at the beginning of 1908, R. Shalom DovBer resolved that R. Levi Yitzchak should succeed him.25 That same year two more of the city’s rabbis passed away, leaving an even wider leadership deficit.26

Situated on the river Dnieper, some 350 kilometers south-east of Kiev and 250 kilometers west of Donetsk, Yekaterinoslav was a thriving industrial city whose Jewish community was tens of thousands strong. Like all large Jewish communities of the time, Yekaterinoslav was a hotbed of tension, with deep fault lines drawn between the advocates of acculturation and secular Zionism, and those who wanted to preserve the traditional ways of Jewish life and learning. R. Shalom DovBer was well known as a staunch critic of Zionism, and of all other forms of secularization, whose chief goal was to advance the authority of the Torah and the practice of the mitzvot. As a chassid who himself bore the Schneersohn name, many in the city were vehemently opposed to R. Levi Yitzchak’s candidacy.27

One of Yekaterinoslav’s most prominent figures was Sergei Paley, a wealthy engineer and industrialist. Sergei’s father, Feitel, was a pious chassid who had named his son Shmarya and given him a solid Jewish education. But the developments of the industrial age had swept Shmarya up on the waves of intellectual and social change. He went to Petersburg to study engineering and returned Sergei Pavalovitch Paley. He raised his own children as acculturated Russians, who could hardly speak a word of Yiddish. “The grandfather could only understand his grandchildren with difficulty, and the grandchildren could not understand their grandmother even with difficulty.”28

Paley’s son-in-law was Menachem Ussishkin, a pioneering Zionist leader who was secretary of the First Zionist Congress in 1897, and went on to head the Jewish National Fund. Between 1891 and 1906 Ussishkin had himself lived in Yekaterinoslav, and under his influence Paley became a powerful backer of the Zionist cause.29

Despite all this, R. Shalom DovBer apparently knew that Paley still harbored some loyalty to his chassidic roots. In a letter addressed to both to “my honored friend the philanthropist, the G‑d fearing and venerable chassid, R. Feitel Paley” and to “his honored son,” R. Shalom DovBer argued R. Levi Yitzchak’s case:

With you now is my relative, the famed gaon (genius) and rabbi, R. Levi Yitzchak Schneersohn, a man who has spirit within him. And as I know him well, the crown of the rabbinate befits him in all requisite aspects. He is a great scholar and utterly in awe of G‑d, possessing intellectual clarity and an easy temperament. He possesses very good and noble characteristics, and knows a thing or two about wise and understanding leadership. You have none better than him… If you desire the good of the city, you should choose the above mentioned rabbi and gaon… with G‑d’s help you will derive satisfaction from him in every regard.30

Paley’s Zionist associates had stated their firm opposition to R. Levi Yitzchak’s appointment, but he decided to reserve judgment until he had met the candidate in person and sounded him out. In her memoir, Rebbetzin Chana recalled that in a one on one meeting lasting from 9pm to 4am, Paley probed her husband on questions of faith and assimilation generally, and on the purpose and import of Kabbalah and Chassidism specifically.31

The combined weight of R. Shalom DovBer’s recommendation and R. Levi Yitzchak’s personal stature convinced Paley to break ranks with the Zionist establishment. He gave R. Levi Yitzchak’s candidacy his full backing. “Such greatness,” he said, “we must not allow to slip away.”32

The Battle for the Rabbinate

Rabbi Yehudah Leib Levine, who served as chief-rabbi of Moscow from 1957 to 1971, grew up in Yekaterinoslav, and recalled the battle that ensued:

The peace in the city was breached, it became like a maelstrom, divided between chassidim, those who opposed chassidism (mitnagdim), and the advocates of acculturation (maskilim). The chassidim wanted Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson. The mitnagdim, the maskilim and the wealthy wanted Rabbi Pinchas Gellman… The debate mounted to the very heavens, coming to blows and desecration of G‑d’s name in every synagogue in the city, and continuing for several months.33

Though the Jewish community’s central committee had a majority of acculturated and wealthy Jews, Paley managed to garner support for R. Levi Yitzchak even in these more secular circles.

Though he did not aspire to conduct his personal affairs in full accord with Jewish law, he strongly believed that Jewish culture could not be artificially reconstructed. The survival of strong Jewish community and identity, he argued, could only be assured through the passionate authenticity and deep Torah knowledge that R. Levi Yitzchak lived and breathed.34

Other members of the Jewish intelligentsia were surprised at how R. Levi Yitzchak combined such breadth of mind with such exacting observance of Jewish law, and with such precise knowledge of Jewish texts. “Schneerson,” one doctor remarked in bemusement, “is a very interesting person, and yet a pedantic.”35 Apparently he was referring both to R. Levi Yitzchak’s scrupulous mitzvah observance and to the pedantic analysis that is one of the notable features of his Torah teachings.36 Previously the doctor had associated both with narrow-mindedness, and he was fascinated that a person of such sweeping ideological breadth found them to be such fitting modes of expression.

Ever larger audiences gathering to listen to R. Levi Yitzchak’s oratory and his fervent depth drew an increasing groundswell of support at the grassroots level. At thirty years of age he was still a young man, and the younger members of the community were particularly drawn to him.37

R. Levi Yitzchak’s opponents, led by another philanthropic industrialist by the name of Moshe Karpas,38 came up with various political schemes to undermine his status and give their preferred candidate more prominence and authority. But Paley was as politically savvy as anyone and always managed to keep one step ahead.39 Eventually a compromise was reached, R. Levi Yitzchak and R. Pinchas, his competing candidate, each took up positions overseeing different sections of the city.40

Once some of the dust had settled R. Shalom DovBer addressed a letter to Paley expressing his deep appreciation for all he had done:

After the trouble that your honor encountered regarding the rabbinate in your community, and with your mighty spirit you stood fast against all the waves, and did not relax until you brought the matter to fruition, seating my uncle’s grandson, the famed rabbi and chassid, R. Levi Yitzchak, on the rabbinic seat in your community, I am very thankful to your honor… In return for this good accomplishment may G‑d help you and give you the merit to always do good things among our brethren, and the Benevolent One should be good to you with all manner of goodness, spiritual and material, and make you successful in all your concerns and endeavors.

I know that it was only your honor who, with forthright heart, deep understanding and courageous spirit, brought this this great thing to fruition. And as I wrote before, so I believe now, that more than what your honor did for the good of my uncle’s grandson, the Rabbi, you have achieved for the good of the community and the city…41

Turning the Tide of Opposition

One local journalist initially penned sharp articles decrying R. Levi Yitzchak as a narrow minded opponent of cultured civilization, and pointing out that he was a descendent of the Tzemach Tzedek who had famously countered Max Lilienthal’s reforms in the 1840s. But after coming to know R. Levi Yitzchak personally he wrote a retraction and apology, expressing his high regard for the new rabbi, and attacking R. Levi Yitzchak’s detractors as ignoramuses who were incapable of comprehending even his casual conversations.42

At one point R. Levi Yitzchak found a veteran shochet (kosher slaughterer) to be overly hasty, not taking sufficient care to ensure that his knife was sharp and smooth. When R. Levi Yitzchak temporarily removed the shochet from his post, other members of the rabbinate took offense at his interference. Apparently with the consent of some his colleagues and superiors, one of the kosher supervisors went so far as to disguise his appearance and present himself as an independent witness to refute R. Levi Yitzchak’s claims. Though R. Levi Yitzchak was able to unmask the witness and vindicate himself, the treachery of his anti-chassidic colleagues caused him great anguish and physically undermined his health.43

The shochet whose laxity had triggered this affair was by no means an ignoramus, but he was a self-declared opponent of Chabad Chassidism. Once the political tension had dissipated he nevertheless began attending R. Levi Yitzchak’s synagogue to hear his weekly discourses on Kabbalah and Chassidism each Shabbat afternoon. Over time he mellowed and began studying Chassidic texts on his own, becoming a close ally of the chassidic rabbi. Despite R. Levi Yitzchak’s relative youth, and chassidic background, the establishment increasingly acknowledged his competence and authority.44

National Concerns

The need to defend Chassidism from its detractors was not simply a question of local politics. Between 1911 and 1913 the highest echelons of the Tsarist government backed a national campaign to defame Chassidim as the barbaric practitioners of a medieval murder ritual. Thirteen year old Andrei Yushchinsky was murdered in Kiev by a local gang of thieves, but local anti-semitic groups conspired with the minister of justice in Petersburg to implicate a Jew in the murder. As the case developed, prosecutors argued that Mendel Beilis, their chosen scapegoat, was a chassidic “priest” or “Tzadik” affiliated with the Schneersohns of Lubavitch. Rabbi Mendel Chein, the Chabad Rabbi of Nezhin whose sister was married to R. Levi Yitzchak’s brother, worked closely with some of Russia’s most prestigious lawyers to coordinate the defense, and R. Levi Yitzchak too was called upon to contribute.45

The blatant anti-semitism embodied by the Beilis case was in many ways a symptom of broader socio-political tensions pitting the supporters of autocratic nationalism against liberal agitators and revolutionaries. These tensions came to a crescendo with the outbreak of World War One in 1914, the Russian Revolution in 1917, and the Russian Civil War in 1918. As the first Passover of World War One loomed, rabbinic leaders formed a committee to arrange the provision of matzah to Jewish soldiers at the front. In one of the few surviving letters concerning this endeavor, R. Shalom DovBer writes that he has been informed from Yekaterinoslav (i.e. by R. Levi Yitzchak) that the community there would send either the sum of four thousand silver rubles or a shipment of matzah.46

In the summer of 1915 many Jews were expelled by government decree from areas adjacent to the front, and Yekaterinoslav saw a large influx of refugees. R. Levi Yitzchak and Rebbetzin Chana played leading roles in the communal effort to provide aid to these unfortunate individuals, who often arrived in the city with no means to support themselves, and even took a young orphaned boy into their own home.47

Among the refugees were several prominent rabbis, including Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski of Vilna.48 When the provisional government came to power in March 1917 R. Chaim Ozer and R. Levi Yitzchak worked with other leading rabbis to establish a united rabbinic congress to represent the Jewish people, and both traveled to Moscow in the summer of that year for deliberations.49 R. Levi Yitzchak also served as a liaison between R. Shalom DovBer and R. Chaim Ozer during the years the latter spent in Yekaterinoslav, and they must have come to know each other quite well. Referring to R. Levi Yitzchak, R. Chaim Ozer once commented, “The world does not know what a scholarly genius stands in Chabad’s ranks.”50

At the Court in Lubavitch

Until the end of 1915, when R. Shalom DovBer left Lubavitch for the greater security of Rostov on the river Don, R. Levi Yitzchak was a frequent visitor to Chabad’s historic capital. Lubavitch was a small market town, nearly a thousand miles north of Yekaterinoslav, which did not even boast its own railway station. But for nearly a century it had been the seat of successive Chabad rebbes, to which chassidim traveled for spiritual edification and material guidance. Many of the students who studied in Yeshiva Tomchei Temimim Lubavitch during this period remembered R. Levi Yitzchak’s visits well.

Rabbi Nachum Shmaryahu Sussonkin, who arrived in Lubavitch in 1906 and went on to serve as the Chabad rabbi of Jerusalem, recalled that in Lubavitch R. Levi Yitzchak was affectionately known as “Leivik.” Honorifics and titles, he explained, were simply unnecessary:

His name preceded him. Everyone knew that “Leivik” was an individual of wondrous depth, a wise scholar both of the Talmud and of Chassidic teachings. As the sages said, “greater than a rabbinic title is one’s name…” When one said “Leivik” it was already known that this name stands for deep wisdom, wondrous knowledge in everything, in Talmud, Chabad Chassidism and Kabbalah.51

Despite his stature and dignity R. Levi Yitzchak associated freely with the students and with other chassidic visitors. In Yekaterinoslav too, he entered fully into the spirit of Chassidic celebrations. On one occasion his detractors denounced him to local authorities for acting in a way that did not befit a member of the clergy. They reported that he had been seen dancing arm in arm with a cobbler, without his rabbinic coat, and clearly under the influence of alcohol. This accusation was not without foundation; the occasion was a chassidic festival, and the cobbler was a fervent chassid.52

Rabbi Yehudah Chitrik recalled that during R. Levi Yitzchak’s visits to Lubavitch he was constantly surrounded by the foremost students and by chassidim who would hang on to his every word. Since he was R. Shalom DovBer’s guest for the festive meals, the students would ask him to repeat their table talk. On one occasion during the mid 1910s he reported that they had discussed Kabbalistic sources for the concept of revolution.53 On another occasion their discussion centered around the discourse that R. Shalom DovBer had delivered earlier that evening. R. Shalom DovBer began the discourse with three questions, and R. Levi Yitzchak presented him with a kabbalistic explanation of the order in which they were presented.54

Hearing a new chassidic discourse directly from the mouth of the rebbe was the highlight of any visit to Lubavitch. To hear such a discourse was to experience a fresh discovery of divine wisdom. And for someone as steeped in Jewish mystical texts as R. Levi Yitzchak was, such an experience was an opportunity to bring the full range of his analytical and exegetical ability to bear, delving far beyond R. Shalom DovBer’s conscious intention.55

During this period R. Levi Yitzchak’s father, R. Baruch Schneur, was also a frequent visitor to Lubavitch, and he made note of his many conversations with R. Shalom DovBer in a personal journal. There are frequent mentions of R. Levi Yitzchak and his family, and the paternal pride is self evident. On the 7th of Adar, 1915 he reported a discussion “about my son Leivik, and his son Mendel, who will begin laying tefillin this coming Thursday… He is a good boy, tremendously excelling in his studies. Generally, all three are good boys… and Leivik guides them on the path of Torah and service of G‑d, and they go in the right and good way.”56 On another occasion he recorded R. Shalom DovBer’s comment that “Leivik has a good head,” noting that “I know, and everyone knows, that the Rebbe (R. Shalom DovBer) holds very highly of Leivik…”57

Democracy, Revolution and Civil War

At the Moscow rabbinical congress in the summer of 1917, R. Levi Yitzchak lodged at the same home as R. Shalom DovBer.58 Under the Tsars, life had never been easy for the Jews, and now that the Provisional Government had come to power there was hope that the future would be brighter. At the same time the leading rabbis of the generation were vying for influence with more acculturated elements within the Jewish community who often sought to undermine the traditional institutions of Jewish life. As the festival month of Tishrei approached the rabbinic leaders who had gathered in Moscow returned home to their communities, agreeing to reconvene within a few months.59 R. Levi Yitzchak accompanied R. Shalom DovBer on the journey south from Moscow.60

The Provisional Government had its own problems to contend with. Russia was still embroiled in the First World War, and was quickly spiraling into economic and social crisis. Workers were striking across the country, and forming communist councils that resentfully agitated against the Petersburg based government. The increasingly uncertain political situation, and ever less reliable lines of travel and communication, magnified the confusion and disagreement among the rabbinic delegates and it became very difficult to coordinate a mutually agreeable time and place to continue the deliberations.61

In the last days of October, 1917 R. Shalom DovBer was traveling from Rostov to Petersburg for meetings with representatives of the ministry of religious affairs. On the way, news reached him that the Provisional Government had been overthrown by the Bolsheviks. Unable to return directly to Rostov he spent a few days in Moscow, where a fierce battle was raging for control of the city.62

Although the Bolsheviks quickly made peace with Germany, Russia was plunged into civil war. Over the course of the next few years Yekaterinoslav changed hands several times, and Jews were often violently targeted by troops on both sides.63 The aforementioned R. Menachem Mendel Chein of nearby Nezhin, was murdered by cossacks under the command of the White general Anton Denikin. R. Levi Yitzchak’s cousin, R. Menachem Mendel Schneersohn of Bobruisk, was murdered in Yekaterinoslav by Nestor Makhno’s anarcho-communist troops (known as “Makhnovshchina” or “the Black Army”).64

Despite all this danger and turmoil, R. Levi Yitzchak continued to fulfill his regular rabbinic duties to the best of his ability. A cache of documents from the summer of 1919, when the city was in the hands of White troops, shows how he handled a complex financial case. Two partners who had brought merchandise to the city and lost a large part of it on the way. R. Levi Yitzchak convened a court of three rabbinic judges to hear the claims, and issued clear cut rulings covering most of the claims. Some aspects of the case required more data before a ruling could be reached, and R. Levi Yitzchak set up an arrangement that would compel the partners to bring the matter before a rabbinic court, though not necessarily before him personally, once the missing data had been recovered. These documents provide a rare glimpse of a rabbi whose authority, impartiality and practicality could be relied on even in a time of civil unrest and general anarchy.65

* * *

R. Levi Yitzchak would continue with his rabbinic duties despite the turmoil all around him, but the outcome of the civil war would drastically change the environment in which he operated. For decades R. Shalom DovBer had been building a network of rabbinic activists, and developing ever closer ties with governmental authorities. In the face of Jewish inter-communal debate and national crisis, he had yet managed to form a unified religious front, which achieved a majority of the vote for the Russian Jewish congress. But the congress was never to meet. The rise of the Bolsheviks would undo many of R. Shalom DovBer’s achievements, Torah judaism would be driven underground, but R. Levi Yitzchak would continue to persevere.

R. Levi Yitzchak’s life in the shadow of communism, his enforced exile to Kazakhstan, and the several volumes of manuscripts that survive from that period are described in the sequel to the present article: Strength in the Soviet Shadow: The Life and Writings of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson - Part Two.

Start a Discussion