PARKLAND, Fla.—There is a certain silence that hangs over funerals, quieter still when those being buried are the young, the innocent. Life moves on: traffic lights change, palm trees shed their giant leaves, but it all seems unreal, or rather surreal. On a typically warm and seemingly pleasant South Florida winter’s day, this silence envelopes Parkland and neighboring Coral Springs, Fla.—the two towns from which Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School drew its students, and its martyrs.

On Feb. 14, a disturbed former student entered the high school and killed 17 people, five of them members of this area’s tight-knit Jewish community. There is nobody here who hasn’t been affected in some way; thus, these communities grieve, two idyllic towns thrust into an area-wide shiva, the seven-day mourning period for the deceased.

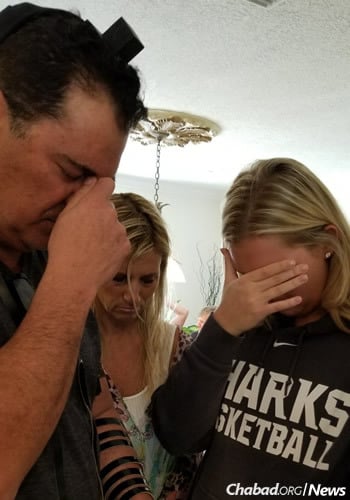

On Sunday afternoon at 1 p.m., the last of the Jewish students, Jaime Taylor (Rivkah Nechamah) Guttenberg, was laid to rest. The scene at her memorial service, held at the Marriott Heron Bay on the border of Coral Springs and Parkland—the very same place where law enforcement had set up a command center, and where parents, family and rabbis had gathered to hear news of loved ones last Wednesday—was one of emotional solidarity. Cars inching their way into the jammed parking area, waved along by the men and women of the Coral Springs police department. A long, quiet, unceasingly polite and understanding line of friends and family waiting to enter the service. Whispers, hugs, sighs, tears. On a sunny Sunday afternoon, they should have been anywhere else, enjoying themselves as people do in Florida, but they were here, at Jamie’s funeral. There were 2,000 people in the room, possibly more—people lining the walls because there were no more seats left; 2,000 people dabbing their eyes with tissues; 2,000 people with a bone in their throat.

Cousins, a teacher, a friend, the parents all shared their memories of Jaime. She loved to dance; her smile lit up a room. Every week she volunteered with children with special needs. She was boisterous; the funeral atmosphere would not have appealed to her. “Why don’t people play poker in the jungle?” she asked her teacher the last time he saw her. “Too many cheetahs.”

But whatever anyone said, on the dais or in the crowd, came back to the wrongness of the scene: A parent should never have to bury a child. That’s just not how it’s supposed to work.

With the service over, as tearfully and politely as they came in, everyone filed back out. Outside, Rabbi Shuey Biston blinked in the bright sunlight. This was the fourth funeral he’s been to since Friday and the second of the day. But the numbers don’t numb the pain; they multiply it. Community members, Jews and non-Jews approached him to exchange some words.

“Thank you for all you’ve done,” said one woman dressed in black.

“We’re one community. This is what we have to do,” the rabbi replied.

Biston is director of outreach at Chabad-Lubavitch of Parkland, and was one of the first on the scene at Douglas. After the Marriott command center opened up, he and Rabbi Mendy Gutnick, the youth and teen director at Chabad of Parkland, made their way there, where they stayed for the rest of the day. Parkland is a small community and approximately 30 percent Jewish, so they knew hundreds of teens who attend Douglas. They sat with parents and comforted children. But as the hours ticked by, the parents who had not yet heard from their kids started to realize what they knew in their gut: Their children had been killed.

Since that day, each following one has been filled with arrangements and technicalities of burial and mourning. On Thursday morning, the first batch of teens came to Chabad of Parkland and Chabad of Coral Springs to say the hagomel prayer, thanking G‑d for being spared. That evening, the Chabad rabbis arranged a memorial to be held at the Parkland Amphitheater. After the planning began, the effort was joined by the city of Parkland; 11,000 people came.

And then the funerals began.

Biston officiated at Alyssa Alhadeff’s, Rabbi Avraham Friedman of Chabad of Coral Springs at Meadow Pollack’s. The sheriff, the medical examiners, the governor’s office, the rabbis say, have all been understanding and cooperative, working to respect Jewish law and tradition with regards to the deceased. Jewish practice is to bury the body as soon as possible, and with the help of South Florida’s Chessed Shel Emes organization, the rabbis worked to see that it happened.

“Every day has been like this,” Biston says as he looks out at the sad, dispersing crowd. “This is a wound that has cut very deep.”

Silence and Building

Rabbi Avraham Friedman remembers where he was and what he was doing when his friend, Andy Pollack, texted him that he feared that his daughter, Meadow, was among the dead.

“It was one of those moments that you’ll never forget, like 9/11,” says Friedman. “I stopped everything, called him and went straight to his house.”

Like Biston and Gutnick, Friedman had also rushed towards Douglas when he heard of the shooting, meeting Rabbi Hershy Bronstein of Chai Center Chabad of Coral Springs NW, the center closest to the school, at the scene. Friedman has been executive director of Chabad of Coral Springs since he moved here in 1991 with his wife, Chanie, and is a fixture in the community. From the school, he went to the Marriott and then prepared to leave for the Pollack home.

What do you say to someone upon whom has dawned the horrible reality that his 18-year-old daughter—a bright, strong-willed girl—is gone?

“The Torah teaches ‘Vayidom Aharon—And Aaron was silent,’ ” says Friedman. “We didn’t talk much. I was there to just to listen, to be there with a friend.”

Friedman has spent each day of shiva at Pollack’s home, a constant presence as the throngs of friends and strangers come in and out of the shiva house. On a quiet side street of Coral Springs, just a few blocks away from the Chabad center, lines of parked cars sidle up on the lush, grassy lawns. Inside, pictures of a smiling Meadow—her Jewish name was Rachel—line a side table in the dining room, as Pollack plays the gracious host to the hundreds who stream through the doors, into the living and dining room, and out onto the back terrace and pool area. Florida Gov. Rick Scott, who has been paying shiva calls in the community, was an unobtrusive presence in the house earlier in the day, spending 30 minutes there doing more listening than talking. Pollack made him feel at home like the other visitors, pulling him out on the terrace and handing him a beer.

He has also made it a point to visit the parents of the other deceased students, people going through the same thing he is. Earlier in the day, he had gone to the home of the parents of Alyssa Alhadeff, and in the days ahead will visit others, including Max Schachter, the father of Alex Schachter, 14, another one of the children killed at the school.

Bronstein, the rabbi at the Chabad center closest to the school, recalls making eye contact with Schachter at the Marriott, a human connection amid the horrors of the day. Schachter lives across the street from Bronstein’s center, and casually attended programs and classes. When Bronstein walked into the shiva house on Sunday afternoon, he knew he had to be there, to organize the mincha afternoon prayer and kaddish, to facilitate the traditional words of bereavement, “Hamakom yenachem etchem b’toch she’ar aveilei tzion v’Yerushalayim—May G‑d comfort you, together with all mourners of Zion and Jerusalem.”

“This is a time of oneness within our community,” says Bronstein. “I couldn’t not be there.”

Back at the Pollack shiva house, Friedman talks with a young enlisted sailor in the U.S. Navy, thanking him for his service. The sailor, a friend of Meadow’s, offers that he would have gladly given himself up to take her place.

“But we can’t change the past,” Friedman tells him. “We can only redouble our own positivity and good works to fill the void left by Meadow’s absence.”

There is a resoluteness in the Pollack house, a sense that something will change as a result of this shattering tragedy, that things can’t go on as they were before. Friedman sees Andy Pollack and the other parents’ passion, and knows they can be a catalyst for good—positive and effective voices of leadership in the current polarized political climate. While there was a time to be silent, the time is coming to harness the goodwill and energy into lasting change.

“The first point is that, as the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] said so many times, there can be differences of opinion, but not ‘the separation of hearts,’ ” says Friedman. “We cannot allow the evil to tear us apart. We need to allow the greater good that is within each and every one of us to come out. The second point is to build. We will find consolation through building, through practical expression.”

Led by Chabad of Parkland, the area Chabad centers have already launched a joint campaign to provide mezuzahs, tefillin and Shabbat candles to every Jewish student at Douglas. That is only the beginning.

“At the funeral, I told the kids: ‘Pay attention to the friend who is troubled, reach out to someone, take a moment to do something as simple as lending a hand. Don’t let this evil define you,’ ” says Friedman. “I was on the dais at the memorial in Parkland. You look out at the crying faces of these thousands of pure, innocent children, who have just seen the face of the most horrific evil; they are open to a message. We have to give that to them.”

Join the Discussion