It was a moonless night: April 11, 1956, Rosh Chodesh, the beginning of the new month of Iyar on the Jewish lunar calendar. Seventeen-year-old Leibel Alevsky, a Russian-born yeshivah student living in Jerusalem, clung to the bed of a small truck as it rumbled down the road leading to Kfar Chabad, also known at the time as Shafrir. Hearing a snippet of a radio report of fedayeen sightings in nearby Beit Dagan, he unscrewed a little light bulb illuminating his rear perch, hoping to make himself less visible. Orchards lined both sides of the dark road, their orange-filled branches making it nearly impossible to see approaching threats.

Entering the village, the old truck passed Beit Sefer Lemelacha, Kfar Chabad’s vocational school geared mostly towards new immigrants, sitting on the right. School had restarted that evening following the Passover break, and the wooden structure’s windows blazed with light as those inside began evening services. The school’s staff had managed to recruit even more students over the vacation period; some were there for the first time.

Around 8 p.m., Alevsky’s ride pulled up at the village center. Climbing off the truck, he heard a sudden outburst of automatic gunfire. It came from the direction of the vocational school.

Reunion in Brooklyn

Sixty-one years later, 12 men in their 80s sat together on a dais in Brooklyn, N.Y. One has been an educator in Casablanca, Morocco, since 1958. Another served as a member of the Rebbe’s secretariat, while a third is the founding Chabad emissary in the state of Florida, today home to nearly 150 centers. Each of the dozen rabbis has accomplished much in their lives.

What brought them together for the first time in more than six decades was recalling the mission they were collectively sent on by the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—to lift the spirits of a broken Chassidic village and a fledgling Israel under daily terror attack.

On that Wednesday night in April 1956, Arab fedayeen (terrorists armed and trained mostly by the Egyptian government) entered and attacked the village, leaving five children and one teacher dead at Beit Sefer Lemelacha, murdered in cold blood while they prayed.

Speaking at a farbrengen one month later, the Rebbe stated that he would be sending a group of yeshivah students to Israel, whose mission would be to strengthen the traumatized community. The Rebbe chose the students, personally overseeing an itinerary that would take them through five European countries and then throughout Israel, their time filled with meetings, classes, speeches and farbrengens (Chassidic gatherings meant to educate and inspire), a schedule stretching from 15 to 18 hours a day.

It was to mark this groundbreaking mission that all 12 men gathered together as a group for the first time since 1956, on Oct. 15 in the main study hall of Educational Institute Oholei Torah in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., at an event organized by Vaad Talmidei Hatemimim and A Chassidisher Derher magazine. Some 1,500 people filled the hall—mostly yeshivah students—where silence reigned for two hours as the elderly men reminisced, with each other and the crowd, recalling the great mission they were entrusted with by the Rebbe when they were just boys, not much older than the audience members.

“The Rebbe made it clear that we were representing the Rebbe himself,” said one of the 12, Rabbi Faivel Rimler. “And that’s how we were greeted [wherever we went]. It was amazing.”

The Rebbe’s response of not attempting to explain the tragedy, but instead striving for the future—healing through growth and in this way, conquering death and evil itself—both saved a village and raised up a country.

Murder in the Village

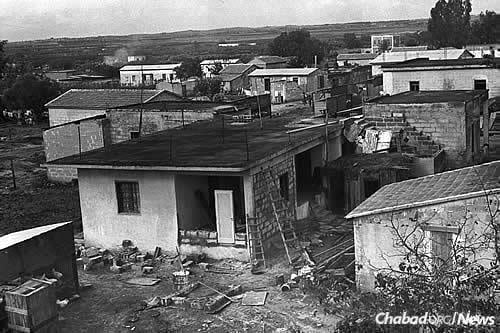

Now a sizeable community in the heart of Israel, Kfar Chabad began as a tiny settlement. It was founded in 1949 on the ruins of an abandoned Arab village and populated, incongruously, by Russian Lubavitcher Chassidim, survivors of both the Holocaust and the Soviet Union’s decades-long assault on Jewish life and practice.

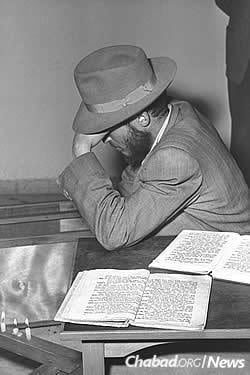

There, bearded men rose early to study and pray before heading out to work the fields, while their wives and children raised chickens and turkeys.

Life in this new place wasn’t easy. Nevertheless, at the Rebbe’s behest, the Chassidic villagers focused not merely on rebuilding their own community (almost all lost loved ones in the war, and most still had family members locked away behind the Iron Curtain), but had thrown themselves into Jewish communal work in their adopted homeland, with one of the results being Beit Sefer Lemelacha, a vocational school teaching carpentry and agriculture. The school drew teenage boys from across Israel, mostly from disadvantaged Sephardic immigrant families.

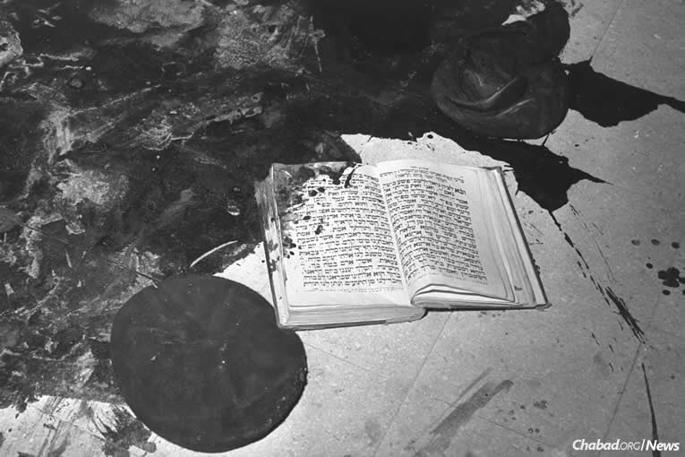

Then came the attack. That night the school’s three teachers and 50 students had been quietly reciting the words of the Amidah, the silent prayer. Suddenly, the lights went out—the fedayeen cut the electricity—and gunshots exploded through the synagogue doors. Everything happened quickly after that. One teacher, a young yeshivah student named Simcha Zilbershtrom, yelled for the children to hit the floor.

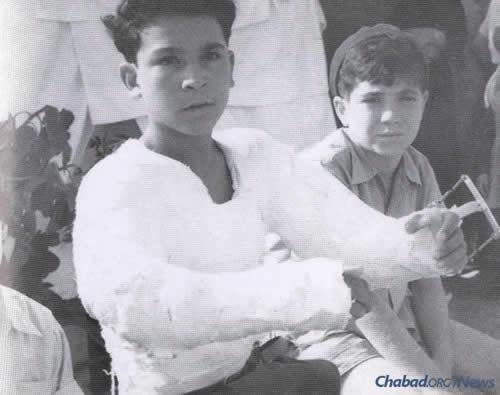

“When the door was breached, the bullets flew straight into the center of the room,” student Asher Kadosh would later remember. He and his younger brother, Meir, had emigrated from Morocco just six months earlier and arrived that day to the school for the first time. “I hid to the left, behind the room’s entrance door, and suddenly, I felt someone fall on me. It was a heavy darkness, but a few seconds later I moved aside, and I recognized our teacher, Simcha, lying on the floor. He was bleeding very badly.

“That moment I began to realize what was going on, and I started calling out my younger brother Meir’s name, but I heard no response. I crawled over to the place where he had stood before, and the teacher, Reb Meir Friedman, struck a bunch of matches, and that’s when I saw that Meir wasn’t hurt. The school’s director, Reb Yeshayahu Gopin, was throwing children out the window so they could get out until the storm passed. As soon as he saw me, he lifted me up in his hands and threw me out through the first-floor window, and from there I ran to our dorm rooms. We had no idea if the terrorists left or not.”

“Within a minute [of hearing gunshots], someone sped down the road on a bicycle, and said people were shot and that the Arab infiltrators were still there,” recalls Alevsky, today the head Chabad emissary in Cleveland. A group of men near a car in the village center grabbed the few odd firearms kept in a small defense locker nearby and rushed towards the school.

“We got there not five minutes after the shots; blood was everywhere,” he remembers. “No one knew what to do because no one knew where those guys were. The orchard was very close to the school’s structure; they could have been hiding there.”

School director Yeshayahu Gopin’s daughter, Raizel, was 14 at the time. She was at a Torah class for girls that evening when the shots rang out. Alarm swept through the village as the girls ran home through the pitch-black streets. “I got home, and my mother was in a panic,” she recalls. “She heard that there was a shooting, but she didn’t know what was going on and had no way to find out. It was a very primitive place then. No phones, hardly any electricity.”

Shortly after the attack, her father ran into the house with a few of the boys—scared 13-year-olds with wide eyes and blood stains on their clothes.

“My father’s hands and clothes were covered with blood,” she remembers. “After he checked that we were alright, he ran back to the school,” leaving the boys to be cared for by his family.

Kfar Chabad had one telephone, which they used to call the police, and two vehicles: the yeshivah’s truck (the one Alevsky had ridden in that night) and another driven by Velvel Zalmanov, who had it through his job with the Dubek cigarette company. Zalmanov’s house was right next door to Beit Sefer Lemelacha, and he was one of the first on the scene. The men grabbed the available vehicles, and drove the injured and dying to the hospital in nearby Tzrifin, guys holding old rifles hanging off the sides of the cars to try to prevent further attack.

Simcha Zilbershtrom, 24, and students Nisim Assis, 13; Moshe Peretz, 14; Shlomo Mizrahi, 16; and Albert Edery, 14, were declared dead at the hospital. Amos Uzan, 15, died two weeks later. Many more children were badly injured.

After the Shock, Build for the Future

Morning in Jerusalem came like any other. Simcha’s older brother, Aharon Mordechai, rose early and went to pray. On his way back home, he noticed a newspaper on the stoop, its front page screaming of murder in Shafrir-Kfar Chabad. There, black on white, read the names of the dead, his younger brother Simcha leading the list.

“That’s how we found out that it happened,” remembers Rabbi Eli Zilbershtrom, Aharon Mordechai and Simcha’s younger brother. (Eli Zilbershtrom later married Raizel Gopin.) “There were no phones to call; we read it in the paper.”

Most of the Zilbershtrom children, Simcha included, were born in Germany. The family survived World War II hiding in a village in southern France and arrived in British Mandate Palestine in 1945. Within a few months the family’s father, Binyomin Nachum, passed away, leaving behind his wife, Fradel, and their children. Both Zilbershtrom parents had lost relatives in the Holocaust; Fradel’s sister and mother had perished in Nazi concentration camps. Despite having survived the horrors of the Old World and making it to Israel, her son was now dead.

Simcha had devoted himself to the children of Beit Sefer Lemelecha, becoming a surrogate father to many. His knowledge of French, gained during the war years, proved valuable in befriending and relating to the school’s Moroccan-born students, and they were shattered by his murder. “ ‘Simcha Was Like Our Father’ ” read a headline in Maariv the day after the funeral.

Arabs were launching attacks on Israelis on a regular basis; that decade, 347 Jews were killed by fedayeen. In 1953 in the village of Yehud, a Jewish mother and her two young children were killed after a grenade was thrown into their home while they slept. A year later, the Ma’ale Akrabim massacre left 11 Jews dead, killed on an Egged bus heading from Eilat to Tel Aviv. The Beit Hanan attack in 1955 left four Jews dead, shot and stabbed as they worked the fields. Now, the attacks were becoming more and more frequent; between April 7-15, 1956, 15 Israelis were killed and 49 injured.

Shocked and horrified by this particularly brutal attack, Israeli society had reached its tipping point. Newspapers spent days capturing the country’s despondent mood. “Entering the school’s modest synagogue,” reported Yediot Achronot’s Hertzl Rosenblum shortly after the attack, “was like visiting Kishinev after the pogrom of 50 years ago.”

Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett sent an urgent message to U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld, informing him of the latest fatal raids by Egyptian terror commandos into Israel and highlighting the one on Kfar Chabad the night before. Ambassador to the United Nations Abba Eban met with the representatives of the Western “Big Three” on the Security Council—the United States, Great Britain and France—indicting Egypt “for the murder of Israeli children and their instructor in the sacred moment of prayer,” and calling the attack a “particularly revolting example” of Egyptian President’s Gamal Abdel Nasser’s increasing belligerence.

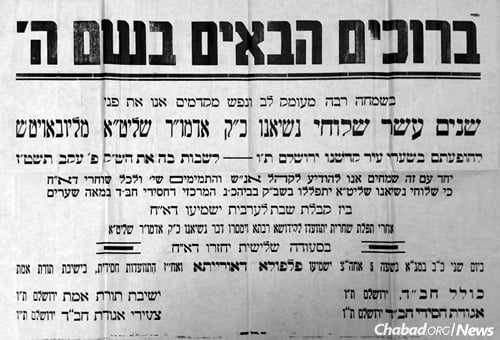

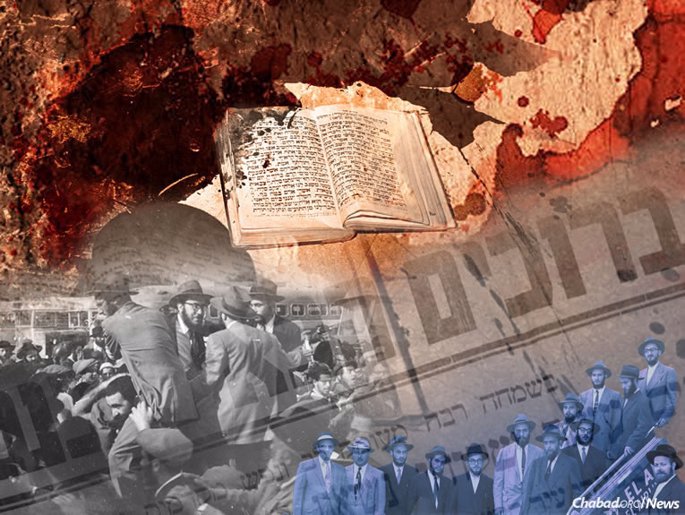

One jarring photo told the story: It showed a blood-stained prayer book splayed open on a white-washed floor caked in thick blood.

With the country turned towards them, the residents of Kfar Chabad were themselves unsure how to proceed. Just a year earlier, a yeshivah student disappeared while walking through the orchards to Kfar Chabad, his desecrated body discovered a few days later.

Now, the stunned Chassidic villagers—faithfully religious pioneers of the land, whose pale Eastern European complexions had bronzed with time under the sun—stood at a crossroads.

Maybe it was time to leave the village, many thought; wouldn’t it be safer in the bigger cities of Tel Aviv, Jerusalem or Bnei Brak?

“What can be said, what can be spoken?” wrote key Kfar Chabad activist Rabbi Ephraim Wolff at the time. “We do not know what to do.”

There was only one place for them to turn. “We now await direction from the Rebbe . . . ”

Within days of the tragedy direction came in the form of letters and telegrams sent by the Rebbe in New York, giving blessings and instructions to the villagers of Kfar Chabad and the broader Chassidic community in Israel. His message? To remain strong, to rededicate themselves to the study of Torah and doing mitzvot, and most importantly, to build. Expansion projects that had begun earlier should be redoubled, new buildings should be erected and new schools opened. Not only were the people not to abandon Kfar Chabad, they were to grow, sink their roots deeper into the soil and continue to serve as inspirations for the entire country. At the same time, this message was reiterated to communal leaders across Israel.

At the end of the shiva mourning period, the Rebbe addressed a letter to “all of the Chassidim in the Land of Israel, to residents of Kfar Chabad, to Chabad’s institutions in the Holy Land, and in particular, to all those affiliated with Beit Sefer Lemelacha” (free translation):

It is my strong hope that with the help of G‑d, Who guards with an open eye and oversees with Divine Providence, that you will overpower every obstacle, strengthen both personal and communal affairs, [and] expand all of the organizations in both quantity and quality. With peace of mind may the study of our Torah, “the living Torah and the words of the living G‑d,” be strengthened and greatened, as well as the fulfillment of its mitzvos with joy, in a manner of v’chai bahem—“living with them.” From Kfar Chabad will spread out the wellsprings of Chassidus, and the Torah and works of our holy rebbeim, until they reach the “outside” . . .

Another telegram came later that day addressed to the directors of Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim in Israel, under whose auspices Beit Sefer Lemelacha fell, this one explicitly laying out what had been implied earlier. “[You] should begin with vigor the construction of the new building of the yeshivah and other buildings in the village . . . ”

At the shloshim—the period marking the end of 30 days after the passing—thousands of men and women from across Israel gathered in Kfar Chabad for the laying of the cornerstone of a new building for Beit Sefer Lemelacha, which would house its new printing school, to be named Yad Hachamishah (“Hand of the Five”) in memory of the slain students and their teacher. Among the dignitaries was Talmudic scholar Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin, who chaired the event; and the country’s two chief rabbis, Yitzhak Halevi Herzog and Yitzhak Nissim. A “who’s who” of the young country’s founding fathers was there as well. Speaker of the Knesset and Histadrut founder Yosef Sprinzak attended, as did Israeli declaration of independence signatory Moshe Kol (Moshe Shapiro, at the time minister of religion and welfare, who was also there, was also a signer). They were joined by National Religious Party founder Yosef Burg; Avraham Herzfeld (also a founder of Histadrut); judicial figure Gad Frumkin; minister of agriculture and Mapai stalwart Kadish Luz; Jewish Agency leader (and future president) Zalman Shazar; Poalei Agudat Israel’s deputy Knesset speaker Binyamin Mintz; future prime minister Menachem Begin; and then-Mapai secretary Yona Kesse, among other rabbis and political figures.

Fradel Zilbershtrom was also there.

“I was pleased to receive news of today’s groundbreaking for the Beit Sefer in Kfar Chabad, especially as you were there and participated in it,” the Rebbe wrote in Hebrew to Mrs. Zilbershtrom. “For all of Israel are ‘believers, the sons of believers’ that the most important part of man is his soul, which is ‘literally a part of G‑d above.’ Since the soul is everlasting, and the purpose of man’s creation and his being placed on earth is to have an effect on the world, including this world [below], therefore when the soul is connected with concrete action in this world—specifically an action that will continue and experience compounding growth, bearing more and more fruit—this is the greatest victory over death and the greatest satisfaction that can be experienced by the soul, especially when these things are being accomplished at the very place where the ‘event’ [i.e., murder] took place.”

His Personal Representatives

Even as the Rebbe wrote letters of consolation and encouragement, he at first refrained from discussing it publicly. The first time he addressed the events, about a month later on the holiday of Shavuot, he explained (in Yiddish) that while “we should not allow ourselves to be negatively affected by trials,” there were some who had attempted to explain the murders by quoting Moses’ words of comfort to his brother, Aaron the High Priest, in Leviticus, following the death of Aaron’s two sons: “Bikrovai ehkadesh—‘I will be sanctified through those near to Me.’ ” The Rebbe rejected this reasoning, alluding to the passage’s ending, Vayidom Aharon—“And Aaron was silent,” stating there could be no logical explanation for the horrific events in Kfar Chabad.

At that Shavuot gathering, the Rebbe went on to announce that he would be sending a group of yeshivah students as his personal representatives to the land of Israel, their mission to lift the spirits of the people there and imbue them with a new energy. Additionally, since the entire Jewish people had an obligation to assist their brethren in Israel, they would also travel on behalf of everyone who could not go themselves.

The next day, a sign was posted in the hallway of 770 Eastern Parkway—Lubavitch World Headquarters in Brooklyn, where the central Lubavitch yeshivah is located—allowing students to volunteer their names for this special mission. In order to be considered for the journey, they would need to have their passports in order and the permission of their parents.

Yosef Rosenfeld was a student at the time and had not planned on putting his name on the list. Summer was approaching, and he wished to remain in the yeshivah, studying Torah throughout. Rosenfeld’s birthday took place a few days after the Rebbe’s announcement, and as was the custom, he sought a private audience with the Rebbe to mark the day.

“The Rebbe asked me if I had submitted my name to his secretariat, to which I replied that I hadn’t,” Rosenfeld said in an interview with A Chassidisher Derher, a story he also recounted at the reunion. “To my surprise, the Rebbe then instructed me to join the list of bochurim who registered for the shlichus. Naturally, I made sure to do so immediately following the audience.”

The final group numbered 12. There were nine representatives from the United States: Rabbi Avraham Korf, today regional director of Chabad in the state of Florida; Rabbi Dovid Schochet, since a prominent rabbinic authority and rabbi of the Lubavitch community in Toronto; Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, who became a longtime member of the Rebbe’s secretariat, and chairman of both Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch (the educational arm of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement) and Machne Israel (its social-services arm); Rabbi Yosef Rosenfeld, now executive director of Educational Institute Oholei Torah; Rabbi Faivel Rimler, today a board member of the National Council for the Furtherance of Jewish Education; Rabbi Sholom Dovber Shemtov, now regional director of Chabad in the state of Michigan; Rabbi Sholom Dovber Butman; Rabbi Shlomo Kirsh; and Rabbi Shmuel Fogelman, later the principal of United Lubavitcher Yeshiva.

Additionally, one representative came from Canada, Rabbi Zushe Posner; another from Europe, Rabbi Sholom Eidelman, the educator in Casablanca; and one from Australia, Rabbi Shraga Herzog.

After being chosen, the nine students in Brooklyn were called in to the Rebbe’s office, where he outlined the nature of the trip they would be undertaking. They would visit Jewish communities in England, Belgium, France, Switzerland and Italy on their way to Israel. The Rebbe gave them detailed instructions, including, for example, that from that day forward until their return, the group must organize a daily study schedule in which all of the shluchim would participate. In Israel, they would visit leaders and Jewish communities throughout the country, holding pre-arranged meetings throughout. Their base would be Kfar Chabad, and any extra time was to be spent studying Torah in the main synagogue, where locals would know they could always reach them. When encountering a speaking opportunity in any of the places they were visiting, they should not turn it down, and make sure to be prepared to share thoughts on both revealed Torah and chassidus.

The group took off on June 27, 1956, landing in London, where they were welcomed by the general Jewish community and held a press conference. In the U.K. they visited Jewish communities in Manchester, Sunderland and Gateshead, before continuing on to mainland Europe.

“My sincerest apologies on the lack of updates, because writing is very time-consuming and the time is very limited,” Krinsky, the group’s secretary, wrote to Rabbi Chaim Mordechai Aizik Hodakov, chief of the Rebbe’s secretariat, in a letter dated July 10 from Zurich. “Especially because of the many journeys in the last two weeks; almost each day we travel to a new city . . . ”

Days later they arrived in Israel, where throngs of men, women and children awaited them at the airport in Lod (now Ben Gurion International Airport). It was 7 a.m., a Friday morning, yet they had come by bus from Kfar Chabad, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Lod, Haifa, Petach Tikva, Bnei Brak, Rishon Letzion . . . The feeling in the crowd was electric. They strained to see the emissaries disembark. When the young men finally stepped off the tarmac, they were spontaneously lifted on shoulders, whisked into the air atop a whirl of dancing feet.

“He who was not at the airport in Lod on that bright morning has never see a great sight in his life,” reads one contemporary report.

“Even the airport personnel and other passengers were swept into the joy,” remembers Butman.

Israel of the 1950s was a very different place. Frequent travel between the country and the United States was unheard of at the time; few Chabad Chassidim there had ever seen the Rebbe (who had succeeded his father-in-law, the sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, the founder of Kfar Chabad—just six years earlier); most had never even heard his voice. Many of the Chassidim had come from the Soviet Union, where the sixth Rebbe had escaped from in 1927, meaning that many had not seen their Rebbe, whether previous or current, in close to three decades, if at all.

The 12 representatives were thus a direct link to the Rebbe’s court, a sign of the Rebbe’s closeness to them and vice versa. At the airport that morning, an unexpected telegram arrived from the Rebbe:

To the shluchim of Chabad-Lubavitch: Welcome upon your safe arrival in the Holy Land. May your visit be with great success in fulfilling its mission, specifically in its main objective of spreading the wellsprings to the outside, and thus hasten the redemption. With many regards to Anash [a Hebrew acronym for anshei shlomenu, a term used to denote the wider family of Chassidim].

Inspiring a Country

The group spent that first Shabbat in Kfar Chabad, a weekend that set the tone for the 28 days they would spend in the country.

“When they came, we traveled to the airport to greet them. I’m not able to describe for you the joy at the airport, and then afterwards on Shabbat,” said Yosef Uminer, a young Israeli yeshivah student at the time, speaking at the Brooklyn reunion. “After they arrived, the atmosphere changed over completely, ‘the city of Shushan shouted and rejoiced . . . ’ I’ll never forget the farbrengen that took place in Kfar Chabad that week. The whole village was there . . . The newspapers, the whole country was speaking about it—this wasn’t just a Chabad thing, this was a country-wide tragedy . . . I just remember the joy. I was young, but it was ingrained in my mind, and I remember it until today . . . ”

The young emissaries, a quarter of the age of some of those who had come to see and hear them, brought with them the excitement and energy of the Rebbe’s environs in New York. They taught the assembled new Chassidic songs, reviewed recently-heard discourses, and spoke about the mission they had been given by the Rebbe. The farbrengen in Kfar Chabad lasted until the early hours of Sunday morning.

That week the group met with children at a summer camp in the village, the students and staff of Beit Sefer Lemelacha, the farmers working the fields surrounding Kfar Chabad, and the leaderships of each and every school and communal organization there. This schedule was replicated in dozens of other Israeli cities and settlements through the length and breadth of the country, from ancient Tiberias to dusty Beersheva, as they met with new immigrants in absorption centers, Torah scholars in yeshivot, and political figures and statesmen.

Even in Jerusalem, where the normally strait-laced Jerusalemites are punctilious about what time they begin and end prayers, and particularly about starting their Shabbat meals on time, a crush of people filled the Chabad synagogue in Mea Shearim, spending hours listening with rapt attention to the American yeshivah students. The gathering lasted until the long summer Shabbat was over.

That evening’s melaveh malkah, the meal that traditionally takes place after the conclusion of Shabbat, was broadcast live over Kol Yisrael radio, an evening hosted by Yediot Achronot’s Shmuel Avidor. (A few weeks later, the group appeared on Kol Zion LaGolah, the country’s national radio-station broadcast outside of Israel—which had a particular impact on Jews living in the Communist bloc—addressing listeners in Yiddish, French and English).

Over the duration of the trip, the Rebbe’s representatives met with more than 20 major rabbinical figures, including the country’s chief rabbis, with whom they discussed Judaism’s views on Israeli-owned shipping lines operating on Shabbat, a contentious subject at the time.

They met with the Belzer Rebbe, Rabbi Aharon Rokeach, a blind, famously ethereal man, who shook hands with each of them (bypassing the hand towel he usually used), and listening closely to the purpose of the shluchim’s mission. The Gerrer Rebbe, Rabbi Yisroel Alter—called the Beis Yisroel—was known as a particularly sharp man, yet stood for the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s young messengers during the entirety of their meeting. As the group left, the Gerrer Rebbe turned to his own followers, demanding “You are Chassidim?” before waving his hand towards the departing emissaries and exclaiming “ . . . these are Chassidim!”

Throughout their travels, Israeli newspapers ran item after item detailing yet another groundbreaking, gathering of children or high-level meeting attended and presided over by the shluchim. The articles paid close attention to the men, especially the Americans, noting that they all spoke Hebrew, even with an Israeli pronunciation. Each piece spoke of the underlying mission the group was there to accomplish.

The same crowds that had greeted them a month earlier were at Lod’s airport once again on Aug. 8 to see them off. They had grown close in the previous month; something now felt different. It was not the emissaries themselves, as individuals, but the spirit they had brought with them that had enlivened the people. Now nine of the 12 emissaries were returning to New York, and it was only with much difficulty that they were able to squeeze through the masses and into customs. “The commotion grows from moment to moment,” wrote one observer in Bitaon Chabad, “everyone feels they still have something to say to them, something to give over.”

The long farewell lasted until the El Al flight was well in the air, followed briskly by the feeling that comes with the end of a holiday. “And now begin the weekdays,” the observer recalled.

“We have a detailed program given to us by the Rebbe,” Sholom Ber Shemtov told a writer from Sha’arim on that first, memorable Shabbat in Kfar Chabad. “And you should know that we come with the Rebbe’s strength, and without that our mission would have no value . . . ” At this, the reporter enumerates the visits and stops the shluchim had on their itinerary before continuing to quote Shemtov, who told him: “But this is not all. There are some ‘items’ on the agenda that we cannot publicize, and other ‘items’ which we, the emissaries, do not even know ourselves . . . The main point is that we are messengers of the Rebbe, and we come here with his strength and his strength only . . . ”

Sixty-one years later, Kfar Chabad not only exists, but thrives, as does the Chabad movement throughout Israel. Whether putting on tefillin with visitors at the Western Wall, distributing mishloach manot for Purim at remote military installations or teaching Torah in Tel Aviv, Chabad bridges the gaps in what can sometimes be a polarized Israeli society.

Israeli society’s response to terror, too, is worlds away from what it was. Sadness transforms into determination and growth—a direct line from the Rebbe’s response to the devastated villagers of Kfar Chabad and the seeds planted by his 12 representatives.

At the end of his Sha’arim article, Naftali Kraus, the writer, having spent Shabbat in Kfar Chabad, tries to sum up the experience:

I did not see everything, and can describe but a part of it here. Shabbat was . . . an unforgettable experience which cannot easily be put into words. However, Sholom Ber [Shemtov] has already said that there are certain “items” whose very existence depends on their remaining indescribeable. Maybe this was just one of those things?

Join the Discussion