The Torah teachings of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, span over 70,000 published pages. A 2011 index of his talks compiled by the scholar Rabbi Michoel Seligson runs to 1,600 pages. Over a period of nearly half a century, the Rebbe delivered 1,558 oral Chassidic discourses; conducted approximately 1,900 farbrengens, each spanning hours; and spoke words of Torah publicly on an additional 1,286 occasions—an estimated 11,000 hours spent teaching publicly.

The Rebbe authored a number of books, and also edited the hundreds of authorized essays published in the 39 volumes of Likkutei Sichot. He also penned many thousands of letters, corresponding with rabbis, political figures, communal leaders, and regular individuals all over the world. Rabbi DovBer Levine, the chief librarian and archivist of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement’s central library, has been laboring since the late 1980s to collect and publish these letters in a series that recently released its 33rd volume.

Nevertheless, the Rebbe’s preferred mode of teaching was the farbrengen, during which specialized teams of scholars would join lay people in remembering and transcribing these talks, which the Rebbe would then painstakingly edit. These talks contained nuanced and novel approaches to the study of everything from Rashi’s Torah commentary to the Talmud, Maimonides, the Zohar, and the entire library of Chabad’s intellectual tradition. The Rebbe also addressed timely contemporary issues, from American foreign aid to the security of the Land of Israel, the moon landing to Soviet Jewry, always through the lens of the eternal Torah.

Counterintuitively, as the Rebbe grew older the frequency of his farbrengens increased, to the extent that Chabad-Lubavitch’s publishing house is still catching up. Thirty years after the Rebbe’s passing, new volumes of his teachings and writings still roll off the printing presses, and in some ways scholars have only begun to plumb the depths of his insight.

The story of how the Rebbe’s teachings reached the published page requires a dive into the nuts and bolts of how the most prolific Torah teacher of the modern age inspired a generation. It is a story that continues to unfold.

‘He is a Gaon’

Rabbi Yosef Ber Soloveitchik, the preeminent head of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, entered Chabad’s central synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway on a Thursday night. It was the 10th of Shevat, 1980, the 30th anniversary of the passing of the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, of righteous memory, and the Rebbe was leading a farbrengen for a crowd of thousands in the synagogue’s main sanctuary. Rabbi Soloveitchik planned to stay for half an hour, but captivated by the Rebbe’s talks, he remained late—until nearly 11:30 pm. Outside in the waiting car, Rabbi Soloveitchik was asked for his impression of the Rebbe. For a moment he was silent, as if unable to find the words to express all that he was feeling. Then he responded: “He’s a gaon, he is a gadol, he is a leader of Jews.”1

Rabbi Soleveitchik, who was acquainted with the Rebbe since their days in Berlin in the 1930s, was no stranger to brilliant Torah scholarship. Still, he had expected anyone delivering addresses freely quoted from the whole of rabbinic literature to arrive with notes, an index card—something. “Beim Rebben iz nisht geven kein zachen—by the Rebbe there was nothing,” he reflected the next day.2

The Rebbe had quoted freely from the spectrum of rabbinic literature for hours, citing Tanach, Talmud, Halacha, Midrash, Kabbalah, and Chassidus to develop a powerful philosophical theory with a decisive call to action—without as much as a glance at a piece of paper. Yet this farbrengen was no different from any other.

For scholars, each farbrengen with the Rebbe was a dazzling display. Rabbi Pinchas Hirschprung, the longtime chief rabbi of Montreal, was a frequent presence. “If you want to enjoy the brilliance of the Rebbe’s Torah, you’ll find it at farbrengens,” he told an interviewee in the mid-1980s. “Watching him pass from one mesechta [Talmud tractate] to the next, breezing through the entire Talmud with genius, mastery, and deep understanding, it’s a spiritual pleasure of a quality that’s hard to describe.”3

For all the breathtaking scholarship of the Rebbe’s talks, the countless everyday people who came found much to be dazzled by, too. Each talk relentlessly revolved around clarifying a single point; all the questions asked and answered along the way reinforced a simple, digestible message. And for some, the sheer poetry of the event—thousands packed together, singing, then listening silently as the Rebbe spoke—was inspiration enough.

When Velvl Greene, a scientist running an exobiology lab for NASA, joined a farbrengen in 1962, he was amazed. “I understood the words but didn’t have enough Jewish knowledge to comprehend most of it,” he recalled. “There was the Rebbe—educated in math and science himself—who spoke of the ‘soul’ as something real, not just an idea. And listening to his every word were a thousand Chassidim, working guys, just like me.” As the Rebbe spoke, Greene recalled a line of poetry that described “standing on the threshold of existence, looking into the depth of the Jewish soul,” and thought, “[This] is my epiphany.”4

The First Farbrengens

Perhaps the first biographical sketch of the Rebbe, published in Hayom Yom in 1957, sums up his youth simply: “He studied with immense dedication and succeeded.”5 Indeed, every first-hand account of his early years mentions his preoccupation with Torah study.6 But, growing up in Yekaterinoslav (today Dnipro, Ukraine), far from the Chabad-Lubavitch movement’s White Russian center, word of his brilliance reached few ears. At least, until his 1928 marriage to Chaya Mushka Schneersohn, daughter of the Sixth Rebbe.

Within months of his marriage, while at his father-in-law’s court in Riga, Latvia, the young scholar was pressed into leading a farbrengen. “He spoke Chassidus for several hours,” wrote Rabbi Eliyahu Chaim Althaus, a senior member of the Sixth Rebbe’s inner circle. He eagerly reported that the young man’s “words were spiced with the midrashim of our sages and Kabbalah; sweet were his words on the ears of the listeners, and all those gathered were amazed.” One Mr. Vekslir present, “a great thinker,” Althaus noted, stayed until 2 a.m. and exclaimed, “I’ve never heard anything like this!”7

But, the occasional pre-war glimpse of the Rebbe-to-be’s genius aside, it would be in the next stage of his life that a wide range of people would be fully exposed to his unique brand of Torah talks. In 1941, days after a near-miraculous escape from Nazi-occupied Europe brought him and his wife to Chabad’s new headquarters in Brooklyn, just over 20 Chassidim, rabbis, and yeshivah students gathered to celebrate his arrival with a seudat hoda’ah, a feast of thanksgiving. The event, which doubled as a farbrengen, began at 9 p.m.

The Rebbe asked participants to pose scholarly questions, requested their names, and spoke until 3 a.m. By then, he had analyzed the Talmud’s discussion of “the four who are required to thank G‑d upon escaping escape from danger”8 through a Talmudic, Kabbalistic, and Chassidic lens—developing the insight that, in classifying all life’s dangers into four categories, the Talmud reflects four sorts of spiritual peril a soul encounters in entering this embodied world. He then put the talk’s central insight to work, applying it to answer participants’ questions and cast light on the meaning of each individual’s name.9

Although reluctant to step into the limelight, the Rebbe soon acceded, at the Sixth Rebbe’s wish, to the request of several local Jews that he speak at 770 Eastern Parkway’s informal kiddush after prayers on Shabbat mevorchim—the Shabbat before Rosh Chodesh.10 The Rebbe would farbreng in 770 on Shabbat mevorchim—the Shabbat preceding the new Jewish month—every week for the next 50 years.11 Unlike in later years, no formal record of his spoken teachings during this period was kept.

The Oral Torah

In 1950, a brilliant 20-year-old yeshivah student named Yoel Kahn arrived in New York from Israel. Having departed for the United States with the intention of studying at the Sixth Rebbe’s yeshivah, upon arrival he learned that Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak had passed away on the 10th of Shevat, while he was enroute.

In the months that followed, Chabad Chassidim quickly coalesced, and began cajoling the Sixth Rebbe’s middle son-in-law, known then as Ramash (an acronym for “Rabbi Mendel Schneerson”) to formally accept the mantle of leadership. The young Kahn began attending Ramash’s monthly gatherings, memorizing the teachings shared and, after Shabbat, writing notes of these farbrengens.

“I wanted to remember what the Rebbe said,” Kahn, who came to be known affectionately as “Reb Yoel,” later recalled. “I wrote points for myself. I never dreamt the Rebbe would edit them.”12 But events overtook him. With the worldwide Chabad movement clamoring for word from 770, one of Reb Yoel’s transcripts was submitted to the Rebbe for his review. To their surprise, the Rebbe edited it. For Reb Yoel, the Rebbe’s willingness to edit transcripts—known as hanachos in Chabad parlance—signaled approval for his nascent effort to record these talks for posterity.13 Reb Yoel quickly recruited a volunteer staff to mail stencil copies of the edited text to Israel, Australia, and Europe.14

On the 10th of Shevat, 1951—the first anniversary of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s passing—with hundreds of people squeezed into the small synagogue in 770 straining to hear, Rabbi Menachem M. Scheerson delivered his inaugural maamer, formally accepting his role as Chabad’s seventh Rebbe.

For five generations, Chabad Rebbes had written their maamarim for publication. But in a private audience weeks later, the Rebbe asked Reb Yoel, “Vos hert zich mit di hanachos—what’s happening with the transcripts?”15 The new Rebbe’s schedule already overflowed with communal commitments. He had no time to personally write his own maamorim. Instead, Chabad’s seventh Rebbe would record his Torah teachings by the same method of the first, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, who, 139 years earlier, had entrusted chozerim (oral scribes) to memorize and put his teachings to paper.

With the publication of the first maamer, Basi L’Gani, a new system took shape: The Rebbe delivered his Torah teachings—both formal Chassidic discourses as well as more general talks—at public farbrengens, after which he received a hanacha (transcript) from Reb Yoel or his team of chozerim. The Rebbe would then edit it, sometimes going through multiple rounds of edits, before it was published and copies were distributed worldwide. This took less of the Rebbe’s time, but, it soon became clear, too much time still. Having shouldered responsibility for a growing global organization—and indeed the concerns of world Jewry alongside the worries of countless public and private individuals who awaited his blessing, advice, and attention—the Rebbe would not edit or publish his teachings for eight years.16

“What can I do?” the Rebbe wrote, “I have no time on my hands.” When the famed Chassidic mentor Rabbi Nissan Nemenov asked the Rebbe to resume editing and publishing maamarim, the Rebbe replied, “I have an unfinished index to Likkutei Torah lying here. When complete, it will illuminate the whole work, but I don’t have the hour and a half it will take.” In a letter to another follower who requested published teachings, he expressed hope that some method could be found to allow “even a small bit of time to contain this great undertaking.”17

Publication may have been on pause, but many thousands of Torah words were spoken at each of the Rebbe’s regularly held farbrengens. There, sitting at a long table, flanked by senior Chassidim and visiting dignitaries, the Rebbe delivered intellectually demanding Torah talks in Yiddish on personal, social, and theological matters. Talks often lasted a half hour or longer, and the Rebbe frequently spoke for four or five hours at a single farbrengen, with pauses for l’chaim and the singing of Chassidic melodies. After each gathering, Reb Yoel and a revolving cast of yeshivah students would convene to spend hours painstakingly recalling each point of the addresses delivered. This was no mean feat.

When put into writing, a single farbrengen often ran to 80 or 100 pages—and it often had to be written without reference to an audio recording. In 1953, Reb Yoel obtained permission to employ a tape recorder to capture farbrengens not held on Shabbat or Jewish holidays.18 But most farbrengens were held on Shabbat—when recording as well as note-taking is forbidden—leaving the chozerim no recourse but their sheer recall.

Despite the difficulty, a trove of unpublished, typewritten Torah material dutifully piled up in Reb Yoel’s archives—with virtually none of it slated for publication, or even the Rebbe’s review. As Rabbi Leibel Altein, later a senior editor of the Rebbe’s talks, recalled, “It’s hard to describe how difficult it was to obtain a copy of a sicha in those days. You had to find someone who owned a hanacha and copy it yourself by typewriter or stencil.”19

Through the 1950s, Chabad’s outreach organization grew ever larger. And as it did, so did demand for published teachings from the Rebbe.

The First Published Pages

Just before Passover 1958, Rabbi Leibel Raskin, a 25-year-old Russian-born yeshivah student, had obtained a copy of every extant hanacha. Active in outreach efforts, he co-founded a committee to share messages from the Rebbe’s talks at synagogues across New York City.

Every week before Shabbat, he’d comb his archive for an appropriate talk, print 60 copies of the hanacha, and equip yeshivah students to share their content in synagogues across New York. Every week after Shabbat, he’d submit a report to the Rebbe’s office, alongside a copy of the hanacha. One week, just before Shavout, the Rebbe returned the hanacha—with his final edits. Ecstatic, Raskin stenciled 500 copies.20 For the first time in years, publication of the Rebbe’s talks became a possibility.

Reb Yoel’s team swung into action, selecting transcripts from the archive, writing weekly drafts in the style of the Rebbe’s original talks, which the Viennese-born Israeli writer Uriel Zimmer then copyedited; then, they arrived on the Rebbe’s desk for final editing.21 For one year, the Rebbe found time to edit a weekly sicha, drawn from the past nine years of his addresses. In 1962, the Lubavitch Youth Organization published the resulting Torah discourses in two volumes that came to bear the title Likutei Sichot—Collected Talks.22

On and off, for the next 30 years, the Rebbe carved out time to edit, re-edit, and footnote hundreds of sichot for publication. While Likutei Sichot’s first four volumes brought foundational Chassidic ideas to a lay audience in an accessible Yiddish, subsequent volumes (alternating between Yiddish and Hebrew) presented scholarly dissertations in a tightly structured format. In 1967, as work began on the series’ fifth volume, a formal organization emerged, Vaad L’Hafatzat Sichot, headed by Reb Yoel and staffed by a team of yeshiva students and scholars. Likutei Sichot’s 39th volume was published in 2001.

No Mere Collection, No Mere Talks

Likutei Sichot’s humble name belies its dazzling contents. As Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin, a leading Torah scholar and editor of the massive Encyclopedia Talmudis, observed: “This is no mere collection, and no mere talks. They contain deep ideas. Here one sees the Rebbe’s mastery of all areas of Torah and his unique way of assimilating the Torah’s revealed meaning and its spiritual aspect.”23

The sichot typically open with a Biblical verse or Talmudic passage which are then subjected to a battery of questions and counter-questions before introducing an idea that both clarifies the talk’s immediate topic, and offers original spiritual guidance, a halachic perspective, or a profound insight into Chassidic philosophy.

The result was a distinctive style. “A passage relating to the fruit of trees in their fifth year takes us through the levels of spiritual reality, an examination of the Baal Shem Tov’s life, and a reversal of our normal understanding of holiness and sanctity—each talk moves from the specific to the general, the finite to the infinite, and back again,” explained Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, chief rabbi of the United Kingdom, in the introduction to his English rendition of a selection of the Rebbe’s talks titled Torah Studies.24

In a given sicha, the Rebbe began by selecting a passage, subjecting it to a rigorous analysis and comparing it with other sources, often crossing disciplinary lines, bringing a literal, legal reading into conversation with a mystical or philosophical principle. In this process, the questions piled up. Then, a foundational new principle would answer them all. As Yosef Bronstein, author of Engaging the Essence, a recent book on the Rebbe’s Torah philosophy, notes, “Even the typical sicha weaves dozens of sources together to develop its key concept and drive home a powerful lesson.”

In commemoration of his mother, Rebbetzin Chana, who passed away in the fall of 1964, the Rebbe devoted a series of his public talks—published in Likutei Sichot—to developing a unique reading of Rashi, the classic commentary to the Torah. Attending to the fine points of wording, grammar, and sequence, the Rebbe identified and extracted deep reservoirs of original insight from a commentary traditionally studied by schoolchildren and scholars alike.25 In 1984, the Rebbe encouraged the daily study of Maimonides’ classic, 14-volume code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah, and began devoting numerous talks to analyzing its text. Another major series of talks commemorated his father, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Schneerson, by explicating his terse commentary on the Zohar and Tanya.

Yet, nowhere was the Rebbe’s exceptional mastery of rabbinic sources and stunningly original analysis more on display than in the talks delivered upon concluding a tractate of the Talmud, traditionally the primary focus of rabbinic scholarship.26 In one famous case, the Rebbe identified a common thread running through Beit Hillel and Beit Shamai’s hundreds of disparate debates across the entire Talmud.

Still, in the quest for truth, not all questions demand earth-shattering answers. Occasionally, the Rebbe even found a simple errant manuscript behind a puzzling text. Rabbi Isser Zalman Weisberg, who drafted sichot for publication in prestigious Yeshivah journals as a student in the late 1970s, recalls detecting a distinguishing trait in the Rebbe’s method—humility.

“Some use the Talmud to express their genius,” he reflected. “The Rebbe simply asked, ‘What does the Talmud, or Rashi, mean to say?”27

Capturing an Ocean

After the passing of the Rebbe’s mother, the pace, length, and substance of his public addresses intensified.28 For a time, farbrengens became a weekly occurrence in 770. The Rebbe began delivering his lectures on Rashi alongside passionate talks on a broad range of Jewish and contemporary issues. But with Vaad L’Hafotzas Sichos—and Reb Yoel—focusing their energy on producing Likutei Sichot, and Reb Yoel now working on a massive encyclopedia of Chassidic philosophy while also teaching in Chabad’s central yeshiva, the infrastructure of transcription struggled to keep pace.29 Yet Jews around the world were clamoring for transcripts of the Rebbe’s latest talks.

At the urging of his family and friends in Montreal, a 17-year-old yeshivah student named Avrohom Gerlitzky began staying up at his typewriter late after Shabbat to detail the content of the Rebbe’s talks in his letters home. Word reached prominent Chabad Chassid Rabbi Bentzion Shemtov, who promptly assembled a team of writers, purchased a Gestetner duplicating machine, and launched an organization, Vaad Hanachos Hatmimim to distribute copies worldwide.30

The team would eventually grow to include 70 chozerim, writers, editors, and managers. In time, under Reb Yoel’s tutelage, this organization would go on to produce a rendering of every talk the Rebbe delivered from 1981 to 1992. Finally, a system sufficient to the challenge of recording the Rebbe’s words had been found.

But in 1985, when two yeshiva students, Gershon Eichorn and Yosef Yitzchak Greenberg, embarked on an ambitious project to print every unedited farbrengen between 1951 and 1981, they found that over 430 farbrengens were missing in their entirety.31 A deep search through Reb Yoel’s archives and several private collections of notes yielded most—but not all—of the missing material, enabling them to publish a nearly comprehensive 50-volume, typewritten Yiddish set—Sichot Kodesh.

But, a language barrier remained. The weekly hanachos appeared in Yiddish, a language not everyone was familiar with. In late 1981, Israeli-born Rabbi Dovid Feldman, who had previously headed Vaad Hanachos Hatmimim,32 was recruited33 to head the newly formed Vaad Hanachos b’Lahak (known by its abbreviation, Lahak) and, alongside Rabbi Yisroel Shimon Kalmenson, and eventually Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook, produce Hebrew-language renditions of the Rebbe’s talks just days after they were delivered.

With the Rebbe’s acquiescence, Lahak’s weekly transcripts would become the first unedited hanachos to appear in a formal print—rather than typewritten—layout. Within the year, they published a book that would come to bear the title34 Toras Menachem—Hisvadiyos, Volume 1. Volume 43, recording the Rebbe’s public talks of 1992, was published in 1994.

In the 1980s and early `90s, even as Chabad’s global network continued to expand and tens of thousands of people beat a path to his door seeking advice and blessing, the Rebbe devoted tremendous time and energy to editing both Yiddish and Hebrew transcripts of his talks.35 Many of the talks edited during these years were subsequently published in the 11-volume Sefer HaSichot series. Beginning in 1987, the Rebbe began editing numerous maamarim—typically drafted for editing by Rabbis Yoel Kahn, Tzvi Hirsh Notik, and, later, Chaim Shaul Brook. These were eventually published in a six-volume series, Sefer Hamaamarim Melukat.

Gathering Notes

On March 2, 1992, the Rebbe suffered a stroke. The flow of his Torah teachings, which had grown steadily greater in his later years, suddenly stopped. During this difficult time, the machinery that had for so long focused on recording the Rebbe’s Torah, now pivoted to re-examining the vast body of Torah material that had never been prepared for print: the many sichot, maamarim, and informal talks of 1951 through 1982.

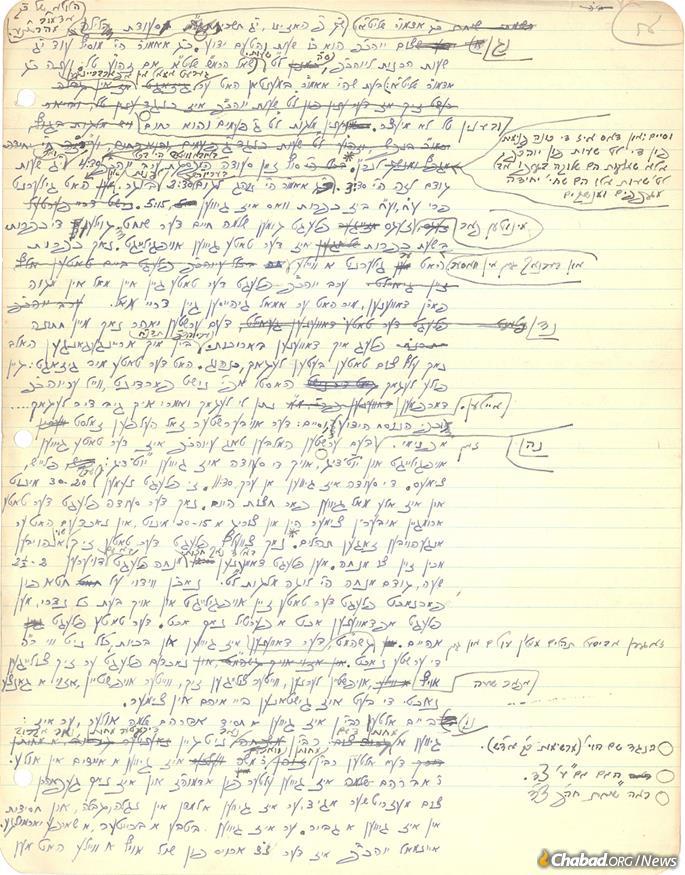

They faced a daunting task. Even after the publication of Sichot Kodesh, the content of entire farbrengens remained unknown, along with hundreds of maamarim and sichot.36 Undaunted, Lahak’s team began the long, difficult task of gathering private notes, audio and video recordings, and piecing together notes in Chabad’s central library—perhaps a simple sketch in the Rebbe’s pen outlining the sources employed in a particular maamar—to painstakingly piece together the complete record of the Rebbe’s teachings, one talk at a time.

For instance, the Rebbe delivered a total of 21 sichot on Sukkot 1952, of which only nine were extant. Employing a combination of Reb Yoel’s notes, private notes provided by Rabbi Moshe Levertov, and an incomplete audio recording, Rabbis Brook, Feldman, and Kalmenson were able to reconstruct and publish all 21 sichot in full. As of 2010, Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook reports, only 34 farbrengens entirely lack transcripts. In the case of about 70, only brief notes have yet been found, and Lahak’s record of around 90 further talks remains incomplete.37 Still, thanks to decades of work, the vast bulk of the Rebbe’s 1,907 farbrengens are now recorded in full. “The material is in our archives,” Rabbi Brook remarked in a 2010 interview, “and our work is in full swing.”

Last month, Lahak published the 83nd volume of Toras Menachem, the finalized, comprehensive record of the Rebbe’s Torah teachings. The latest volume includes talks delivered in roughly the second third of 5736 (1975-76). The number of remaining volumes in the comprehensive record of the Rebbe’s Torah teachings, is, as of yet, unknown.

A World of Torah Still Unfolding

The Chabad movement inherited its passion for publishing from the Rebbe. In 1941, when the Rebbe took the helm of the newly-founded Kehot Publication Society—Chabad’s publication arm—only a handful of classic Chassidic texts were available in print. He encouraged, and often personally participated in, the publication of hundreds of volumes of the six previous Chabad Rebbes’ Chassidic thought, prepared from the Chabad movement’s long-treasured library of original manuscripts. Today, the Rebbe’s own teachings, in all their great beauty, intricacy, and depth, steadily roll off the presses and into libraries, living rooms, and study halls worldwide.

With so much of the Rebbe’s teachings now readily available, scholars, researchers, and academics have begun to journey into this vast reservoir of wisdom in search of common themes, broad principles, advice for life, and practical direction on a host of issues, from emotional wellbeing to Israeli national security and American social issues.

Recent explorations include Prof. Philip Wexler and Rabbi Eli Rubin’s 2019 Social Vision: The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Transformative Paradigm for the World, which outlines the Rebbe’s sometimes-radical, always-insightful visions on social issues. That year also saw Spiritual Education: The Educational Theory and Practice of the Lubavitcher Rebbe go to print. To write the book, Aryeh Solomon, a campus educator and researcher at the University of Sydney’s Department of Hebrew, Biblical and Jewish Studies, spent twenty years pouring over the vastness of the Rebbe’s prodigious output, identifying a cohesive theory of education running throughout it all.

Secondary books rely on primary sources. In the case of the Rebbe’s teachings—those primary sources have sometimes only recently been published. In researching his ambitious overview of the Rebbe’s teachings, Engaging the Essence: The Torah Philosophy of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Yosef Bronstein relied heavily on Toras Menachem’s Hebrew rendition of the Rebbe’s talks and discourses throughout his years of research.38 “Sometimes I’d have to revisit an already-written chapter,” he says, “because a newly published volume contained relevant material.”

This past year saw publication of Levi Shmotkin’s Letters for Life: Guidance for Emotional Wellness from the Lubavitcher Rebbe and Elisha Pearl’s Make Peace: A Strategic Guide for Achieving Lasting Peace in Israel, each book numbering in the hundreds of pages to explore just one relevant area of the Rebbe’s vast body of work.

As the doors to the Rebbe’s teachings open ever wider, it seems the story of the Rebbe’s intellectual contribution to the Jewish people has only begun to be written.

Join the Discussion