The year 1983 was a turning point of sorts for Rabbi Menachem Schmidt. That was the year that the Chabad-Lubavitch emissary almost cancelled Passover Seders at Lubavitch House at the University of Pennsylvania.

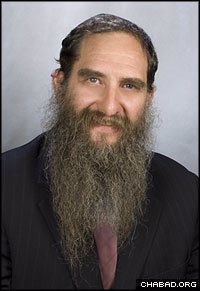

“Things were very, very hard for us financially,” says Schmidt, 53, who last week was awarded a first-ever fellowship by the Avi Chai Foundation for his work in Jewish outreach. “And that’s an understatement.”

Just before Passover, the young rabbi called up his father to ask for some advice. To run Seders for the Jewish students at the Ivy League school would cost $5,000, and Schmidt didn’t have it.

“What do you think if we just cancelled Passover this year?” he asked. “It’s the end of the year. You can have 800 kids dancing for Purim, and that’s less expensive than 120 kids having Seder.”

His father, who wasn’t religious, threw his son – who had embraced Chasidism in college, and earned his rabbinic ordination four years after graduating from Syracuse University in New York – a curveball.

“If you close for Passover,” he said, “just close altogether.”

“That was G‑d giving me a message, alright,” says Schmidt.

With time running short, Schmidt needed to raise the money fast. A friend of his had a wacky idea: Ask mogul financier Michael Steinhardt, a Penn alumnus, to contribute.

“There was a profile in the Wall Street Journal about how Mr. Steinhardt was philanthropic and, despite being an atheist, was interested in Jewish students,” relates Schmidt. “My friend and I wrote to him. Our letter was short, and signed in green ink. We sent it by Federal Express to indicate the urgency, and said that there would be 120 kids at Penn who wouldn’t have a Passover Seder if he didn’t give us the money.”

The next day, Steinhardt’s secretary called the pair. Her boss said that they wrote funny letters, but wanted to know where to send the check.

For the Seder that year, Schmidt prepared all the food with the help of a hired prep cook. Because of the sheer number of people – more than 150 people showed up – he spread out tables in four different rooms.

Since then, Schmidt has dizzyingly added program after program to an outreach repertoire aimed locally and nationally at every single Jew, no matter who, no matter where. All told, tens of thousands of people continue to participate in activities either started or managed by the rabbi, including the Jewish Business Network, Jewish Relief Agency, Jewish Heritage Programs, Lubavitch House and the Old City Jewish Art Center. With each passing year, he helps bring out new emissaries to campuses all over the United States, while at home he fuels a Jewish revival in Philadelphia’s downtown.

Sealing the Deal

Born in northern New Jersey, Schmidt was an accomplished guitar and piano player when he got to Syracuse. He studied communications and was set for a career in the advertising industry or television, when he went to a meeting of Jewish young adults at Lubavitch World Headquarters in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn.

Soon after, he immersed himself in the study of Chasidic thought at the Lubavitch-run Rabbinical College of America in Morristown, N.J.

His classmates paint a picture of a tireless individual, whose methods were a bit off the wall. When it came to the weekly campaigns into neighboring communities to provide Jews with Jewish outlets – a practice known as mivtzoim in Hebrew – Schmidt was known as the idea-guy. He once wanted to drop leaflets of 10 verses from the Bible and rabbinic literature over Atlantic City, but demurred when he figured out the cost.

“For Menachem, you had two options when you went out to do mivtzoim,” says Rabbi Tzvi Freeman, a Toronto-based scholar and author, and member of Chabad.org’s Ask the Rabbi team. “If one was normal and the other was crazy, you did the crazy one.”

One example that sticks out in Freeman’s mind is what Schmidt did one Tisha B’Av, the summer day of mourning for the Romans’ 1st century destruction of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem.

“What do normal people do on Tisha B’Av?” begins Freeman. “You’re fasting, so you’re hungry. And given that the Romans managed to make a mess of things right in the middle of the summer, you want to cool off and take it easy.

“Not Menachem,” he states. “Schmidt’s idea was to see how many students could fit into this tiny little Volkswagen, drive up to some camp in upstate New York, and put on a play for the campers. And when you do that at one camp, you drive to another camp.

“We got to watch all of these kids sitting in the shade, drinking their Kool-Aid,” laughs Freeman. “It was perhaps the hottest day of the year.”

Campus Life

A couple of years later, Rabbi Avraham Shemtov, head emissary in Philadelphia, appointed Schmidt and his wife Chava to head up outreach activities at Penn, then only the eighth college campus to have a full-time Chabad House.

Schmidt started out by rallying Jewish students together. He learned with them, invited them over for Shabbat meals, and even played guitar in the Baal Shem Tov Band that he helped form as a rabbinical student.

The emergency Steinhardt donation came three years later, followed quickly by further investments from the businessman. With help from Rabbi Ephraim Levin, Schmidt formed the Steinhardt/Cayne Jewish Heritage Programs, a national pioneer in peer-to-peer programming that, since 1993, has engaged more than 150,000 Jewish college students and alumni in mentoring and networking events.

In 2000, local Jewish community member Marc Erlbaum co-founded the Jewish Relief Agency with Schmidt. The organization brings thousands of people together once a month to distribute food to Northeast Philadelphia’s poor Jewish residents. Last year, the Schmidts, together with their daughter Chani and son-in-law Rabbi Zev Baram, opened the Old City Jewish Art Center, an exhibition gallery that hosts a Shabbat dinner once a week for more than a thousand people.

It was the art center that initially attracted the Avi Chai Foundation.

“It just really bothered me that there were thousands of people walking down the art corridor of 3rd Street the first Friday of every month, and there was nothing Jewish for them,” says Schmidt. “I was convinced that there had to be a place around there that was empty and available.”

The Bork family ended up providing the space, and have been immensely helpful with the project ever since. For its first Shabbat, the center displayed photographs taken by Philadelphia native Steve Belkowitz, as well as spiritual quotes gleaned from the teachings of the Rebbe by Tzvi Freeman and other writers.

“We opened the door, and 1,000 people came in three hours,” says Schmidt. “We made Kiddush every half hour, and I gave over some words of Torah.

“We were blown away by the response,” he adds. “We want to take the idea a few steps further, to explore the connections between the arts and Jewish spirituality from a Chasidic perspective.”

Some might see a religiously-themed art gallery as somewhat of a non-starter, says Yudi Bork, but it was wacky enough to work.

“This was an opportunity to show people in Philadelphia about Shabbat and art at the same time,” he explains. “It grew unbelievably.”

To many people, the number of programs that Schmidt manages is staggering. From a cluttered and cramped office in the Italian Market area of South Philadelphia – he moved there in 1990 – he serves as rabbi of the city’s historic Vilna Congregation, retains his position as executive director of the Lubavitch House, and helps give guidance to a network of more than 130 campus-based Chabad Houses worldwide as president of the Chabad on Campus International Federation, which was born in 1992. In October, he saw through the groundbreaking of a new home for the Lubavitch House, the Perelman Center for Jewish Life at Penn.

“We are very proud of Menachem and Chava, and their activities,” says Shemtov. “So is the community at large. He is a source of pride to us and source of inspiration to others.”

In addition to JHP, the relief agency and the art center, Schmidt leads students and young adults on free tours of Israel through Taglit-birthright israel and Mayanot.

“He’s a serial creator of good works,” states David P. Stone, chair of the selection committee that conferred the Avi Chai Fellowship, an annual $75,000 grant for three years, on Schmidt.

Schmidt plans on using the award to beef up programs at the art center and expand JHP’s mentoring initiatives at Chabad Houses nationwide.

“Everyday is a new opportunity,” says Schmidt. “This mentoring program, for instance, is very important. There are a lot of students, both in and out of school, who are looking for both Jewish involvement and professional training. Through its network of leaders in business, medicine, science and the arts, JHP can provide both.”

Different Strokes

Schmidt looks at the rough patch of 1983 as a lesson in never being satisfied. It’s a lesson that he says was reinforced again and again by the example of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, and drilled in him by his spiritual advisers, or mashpiim, and fellow emissaries.

“Some of the clearest answers I’ve gotten from the Rebbe are for taking the bull by the horns and running with it,” he says. “For the Rebbe, innovation was always important, new ideas are important. If you’re living in the past, you can never move forward.”

It didn’t take long for people like Steinhardt, and a whole swath of local supporters – both influential and not – to endorse that revolutionary vision. Effectively Jewish universalism with a twist, the outlook demands that every person, no matter his or her age or station in life, reveal a core of Divine goodness. The trick is providing a wealth of options for Jewish involvement by doing away with barriers to people’s entry into Jewish life.

For some, that means giving them the opportunity to help the poor by going door-to-door with boxes of food. For others, that means taking them to Israel. For others still, it means sending them to yeshiva, giving them a bowl of cholent on a Shabbat afternoon, or bringing out a Chasidic-themed rock band to entertain a crowd.

“Menachem cares about every Jew,” says developer Gary Erlbaum, vice chairman of the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia, who has known Schmidt for 20 years. “He never seeks the limelight, and affects people in an extremely positive way.”

Erlbaum, himself, was a bit of a tough sell early on.

From the time they first met, Schmidt “had been quietly, and self-effacingly, asking me every few months to support his projects,” relates Erlbaum. “I liked his style, in that he was always quiet and, while persistent, was not aggressive.”

It wasn’t until Erlbaum effectively put his children’s Jewish educations into Schmidt’s hands that he became a full supporter.

“I brought him home to meet and learn with my family,” he says. “My family instantly took to him. We met every week, and today my sons are not only frum, but they are all extremely active in the Jewish community.”

Patricia Cayne, a financial backer and co-founder of JHP, calls Schmidt “the Pied Piper.”

“As a black hatter, he just has an appeal to young people. It’s very unusual,” she explains. “It appealed to me. I never doubted his authenticity at all.”

“I remember exactly the first time, in 1982, that I met Menachem,” says Yitzchak Rosenbaum, an Israel-based business attorney. “I was in law school and on the second day of Rosh Hashanah, I came out to the Lubavitch House with my wife. We had just become vegetarians, and he asked us to sit down for chicken dinner.”

Rosenbaum soon volunteered to help with Guideline Services, a suicide hotline that Schmidt formed at Penn after a rash of student suicides.

“We just kept volunteering,” he says.

It was Rosenbaum who helped Schmidt write the letter to Steinhardt.

Says the attorney: “With Menachem, with just a little bit of money, he’ll conquer the world.”

For his part, Steinhardt credits Schmidt and the JHP with revolutionizing programming for Jewish young adults.

“I think this program with its emphasis on peers teaching peers has been both innovative and [influential],” writes in a letter to fellow supporters. “Some important Hillel innovations are in large part [due to] Rabbi Schmidt’s ideas.”

He doesn’t remember his first $5,000 donation to the rabbi, but Steinhardt says that he cherishes a relationship with the rabbi that has spanned decades.

“I’ve been a supporter of JHP primarily because of Menachem, who I think is a wonderful, giving and thoughtful person,” says the financier. “He has a vision that he has been able to translate into reality.”

In a moment of self-reflection, Schmidt admits that, just as in 1983, winning the Avi Chai award can be another defining moment.

“I’m scared out of my mind,” he reveals. “It’s a big opportunity. We’re put here on this earth for a reason, and you can’t walk around thinking you’re a big shot because you got an award.

“Working with others, especially other emissaries – an incomparably selfless, resourceful and dedicated scholarly force – is the most important thing,” he continues. “The blessing for success that we get comes specifically through that.”

Join the Discussion