Eight young students sat around the table celebrating the anniversary of the passing of the first Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi. In between singing stirring melodies, they ate bread, herring and hot potatoes, in the "Tailors' Synagogue" in Berdichev, Ukraine.

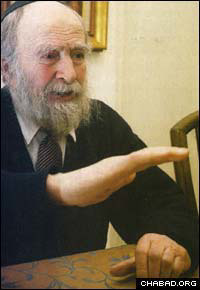

Velvel Averbuch, 84, a resident of the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, N.Y., remembers the evening well.

A sign of the times, the doors were barred shut from the inside with heavy planks of wood. The youngsters had pushed some heavy benches in front of them, planning for the worst. Their two teachers' voices echoed from the walls of the relatively empty synagogue, inspiring them to keep learning Torah and be meticulous in their daily studies.

Most of the group on that 1938 night came from cities across the Soviet Union. Constant harassment by Communist authorities forced them from their homes, lest their parents continue to be hounded for not sending the children to government schools. The students came to Berdichev of their own accord in order to study in the Tomchei Tmimim Lubavitch underground Jewish school system. Some had traveled from city to city, spending a brief amount of time in each underground school in order to elude the watchful eyes of the Soviets.

Berdichev, with a dozen active synagogues, was relatively better than other locales. Still, before meetings such as this, the students regularly practiced their excuses should they ever be discovered. Chasidic gatherings were strictly illegal, and its attendees were sure to be found out as foreigners.

A Late Night Discovery

As the evening moved on and a spirit of camaraderie filled the room, the sound of heavy hands on the door outside sent the students scrambling. As planned, the two teachers jumped from their seats and hid in a side room containing piles of firewood. After a few pushes from the outside, the door gave way. In walked the local police.

"We are partying here," exclaimed the students.

The investigators weren't buying it. After a search, they found the elders.

"One-by-one they called us to the side," says Averbuch, one of only two living today who took part in that gathering. They "interrogated each one of us separately."

A policeman lifted up Averbuch's kasket, revealing his yarmulke.

"What is this?" asked the official.

"It is for the cold."

Next, the man lifted up Averbuch's shirt and tugged at his four-cornered garment bearing tzitzit, the fringes commanded by the Torah.

"My father, prior to his passing, asked me to wear this everyday," explained the child.

None of the excuses worked. When they completed their interrogations, the police marched the children to the local station, the teachers in tow. One officer guided the group in the front, while another guarded it from behind.

Picture in the Cold

The next morning, the students were hauled away on truck to the local headquarters of the KGB. Workers there confiscated their tefillin and sheared away their tzitzit. A smirking officer explained that they didn't allow any strings in jail because they were worried about the prisoners committing suicide.

In the freezing cold, the students were ordered to line up for a group picture.

For the following months, the students endured twice daily interrogations designed to extract information proving the existence of organized Jewish learning in Soviet realms. According to Averbuch, the KGB knew everything about each one of the students, but wanted to have documented confessions.

It was a tortuous month. No one would eat the soup, fearing that it was made with non-kosher meat. The hard piece of bread rationed out to each of them was difficult to consume.

But even under the worst conditions, they adhered to Jewish law as best they could. They washed their hands when they woke in the morning, and again before eating bread, despite the fact that they only received a meager daily allotment of water.

The worst came when the authorities brought out one of the teachers.

"At one point, they brought our beloved teacher, Rabbi Moshe Rubinson, into the interrogation room together with me," relates Averbuch.

"Who taught you Torah," asked the officer.

"I was not connected to any learning of Torah," responded the child. "Therefore, I have no teacher."

The officer then turned to Rubinson.

"Who taught Torah to the young lads," he asked again.

At that point, the rabbi admitted to the crime of teaching Jewish students about their heritage and took full responsibility for the underground school.

Averbuch, who loved his teacher so much that he had resolved to stay in prison, come what may, blurted out: "You are a liar."

Rubinson's confession was all the KGB needed. A recent discovery of his file by Rabbi Shlomo Wilhelm, a Chabad-Lubavitch emissary in Zhitomer, Ukraine, confirms that the educator took all the blame. Even more, his testimony only implicated others who had already died by that point.

Rubinson and the other teacher were imprisoned for a year. He escaped from the Soviet Union in the late 1940s.

The "Orphanage" and the Escape

For Averbuch and the other students, the journey was more circuitous.

After their month in prison was over, the six youngest were sent to the Home for Education for Orphans, despite the fact that their parents were alive. Similar institutions dotted Eastern Europe back then, fulfilling the Soviet policy of attempting through education what torture and starvation could not: the ultimate rejection of their Jewish identities.

But the children proved resistant. After a couple of months, they held a Shabbat prayer service, infusing their prayers with fervor and the chanting of Chasidic melodies. Upon discovering the service, the home's administrators threatened to transfer them.

"You act as if you are still in Jewish religious school," remarked one of the staff.

Still, the students persisted, eventually befriending some of the home's workers so that they could leave the grounds under the pretext of play. One day, two of the students received permission to play in the snow, but took the opportunity to go into the city and get a pair of tefillin. One after the other, each child secretly donned tefillin.

Over the next three weeks, they obtained Jewish holy books and learned from them in secrecy. On one trip to the city, two students met Rabbi Michoel Teitelbaum, who worked in the underground system, who told them of a plan to smuggle them out of the school and from there to other cities.

The plan called for them to meet Teitelbaum the following Shabbat. As discussed, they asked for permission to go play. Leaving in groups of two, the boys kept walking and regrouped at a planned meeting place. Teitelbaum later gave them train tickets.

The escape – its anniversary occurs this week – was successful, and most of the students eventually arrived in Georgia, where it was relatively easier to live an open Jewish life. Years later, some made it out of the Soviet Union all together.

"When I relay the events that happened 70 years ago," says Averbuch, who just married off three of his grandchildren in Israel, "I think to myself, what would have been with us had the Chasidim forgotten about us once we were arrested?

"I thank G‑d for [the] kindness that He did for me and my friends."

Join the Discussion