Batya Berg never had children of her own, but her days are filled with caring for the needs of her young charges. Some of them have no mothers, others are orphaned from their fathers; all of them are bewildered, wounded, and intimately familiar with poverty, illness and despair.

When enough of these children were receiving a warm meal, when they were all engaged in an afternoon activity of their choice, when sad eyes began to twinkle with joy, Batya was able to take the time to talk to me about the events that led her to tend to these children.

A Glimpse Into Another World

That day, she begins her story, she didn’t even have a cough, just a bit of fever. Were it not for her traveling plans the following week, she would’ve rested and allowed herself to ride it out. But the doctor, concerned—Batya was no longer a young woman—ordered tests.

The X-ray revealed an inflammation in the lung. Antibiotics promised hope of a speedy recovery. At the end of the week, however, her breathing had become labored, strained in a strangulated way, and the doctor had ordered her to the hospital. Intravenous, an oxygen mask and more antibiotics were administered. By the time it was discovered that the inflammation was not due to pneumonia but to a childhood illness in the past, Batya had taken a definite turn for the worse.

“Master of the Universe, when You took away my six sons and a daughter . . . when my husband disappeared . . . I never questioned why. But please don’t take my one and only daughter from the world.”Batya lay in the hospital bed under a thin blanket, feeling hot one minute and chilled the next minute. It seemed to her that a huge weight was wedged on her chest; she just couldn’t fill her lungs with enough breath. Limp and weak, she barely had the energy to smile at Avraham, her husband, standing at her side, his forehead creased with worry, and she kept slipping in and out of wakefulness. She was suffering from an allergic reaction to the medicine.

Then it all began to happen at once. The jarring bleeping of a machine, the urgent voice shrieking through an intercom, the sound of running footsteps, and then suddenly the image of her husband faded into a blurry haze, and the pain subsided. I’m not ready to die, was Batya’s only thought.

She lifted her gaze and saw her mother running toward her—her mother, who had long since passed on. She jerked forward, wanting to sink into her mother’s embrace, but she felt as though she was walking in slow motion through a thick, impassable marsh. She wanted to cry out, but she couldn’t find her tongue.

“What is going on?” her mother asked.

“She’s being judged by the heavenly court,” came the reply.

A shock wave passed through Batya. It’s all over, then? she shuddered. But I didn’t yet accomplish anything. I left no legacy behind. This cannot be.

Her mother’s voice sounded again.

“Master of the Universe,” she said. “When you took away my children, six sons and a daughter, in Babi Yar, I never asked why . . . The two years when my husband disappeared inside a Russian prison because of his sacrifices for Torah, and I didn’t know whether I was a widow or not, I never questioned why.

“I lived 91 years and never even became a grandmother, but I never protested or cried, ‘Why do I deserve this?’

“It cannot be that now you should take my one and only daughter from the world. Please, give her another chance.”

A New Lease on Life

Batya trembled violently; she coughed and sputtered, and then a sudden spasm went through her body. She opened her eyes. There was a face hunched over her—probably a doctor. He seemed to be doing something, checking her pulse, maybe. He was talking to someone who was standing by her side—her husband? Yes, it was her husband.

Her eyes closed again. She felt spent, sapped of her natural vigor. Her breathing came in ragged gasps; her forehead was drenched with sweat. She didn’t have the strength to speak. But the thoughts and emotions crowded her brain, heaving and swelling like a tidal wave.

Her seven siblings had been among the tens of thousands of innocent Jews that were herded to the suburban ravine of Babi Yar Mama, dear, dear Mama. How much Mama had suffered. She herself had been a little girl on that horrific eve, when the Nazis invaded their city of Kiev and burst through the door of their home. Hiding under a bed, cowering in fear, she’d managed to evade them. Her parents, too, had escaped their clutches. But her seven siblings had been among the tens of thousands of innocent Jews who were dragged out of the ghetto and herded to the suburban ravine of Babi Yar, where the Einsatzgruppen kept up a steady volley of gunfire for two frightful days.

With a start, Batya realized that today was the day of Mama’s yahrtzeit—the anniversary of her passing. The indelible vision of Mama had transported her to a different world, a different time; a life of hardships and hunger and fear, and the excruciating pain of losing children.

Childhood Behind the Iron Curtain

When the war ended, their poverty didn’t. They lived in a basement, seventeen steps below ground level. Each time Batya raised her eyes, she would be greeted by the sight of feet: feet walking, running, moving past her vision. “It’s so sad,” she said to her father one day. “From all my youthful days, I’ll remember only people stepping on me with their feet.”

Father’s eyes had crinkled into a smile. “You think so?” he asked. “Isn’t that a pity? When you lift your eyes you see feet and it makes you sad, and I when I lift my eyes I see the stars twinkling in the sky and it makes me happy.”

Mama. Tatte. A wave of longing engulfed her. What joy they had exuded. Hunger? Fear? Tragedy? Nothing prevented their ability to see the good within the bare walls of their homes; their happiness at being able to fulfill G‑d’s commands, though each mitzvah required sheer willpower and tremendous courage. And when evening fell, the family would sit and count the angels that were created that day from the mitzvahs they’d fulfilled.

Someone shuffled into the room. Batya half-opened one eye. An orderly was placing a tray of food on her bed stand. The smell of chicken nauseated her now. But the soup reminded her of Mama’s soup . . .

Mama would take the kilo of bread they received once a day, and cut it into four portions. Three portions she crumbled into a bowl and poured warm water over it. After a while, when the water had absorbed the flavor of the bread, Mama would serve the meal; first the water, “soup” to warm their frozen innards, then the slush of sodden crumbs.

Batya pictured Mama carefully wrapping the fourth scrap of bread. “It’s for your breakfast,” she would say. “We must eat to live, to hang onto our souls. You must eat to grow.” But still, she was always hungry. And now, lying in her hospital bed, she recalled Mama’s gentle hands as she placed them on her rumbling stomach. “Murgen, murgen” (tomorrow, tomorrow), Mama would beg her stomach to understand. “Rudehr nisht, boich. Ich hub den broit un ich gib dir nisht?” (Don’t rumble, stomach. Do I have then the bread and I’m not giving it to you?)

A Two-Year Nightmare

Even when Father disappeared, Mama clung to her joie de vivre. It was during the period of the infamous Doctors’ Plot, in which Jewish doctors were accused of planning to poison government officials. As a result of the accusations, many doctors and Jews were imprisoned and executed—scapegoats for all of their nation’s woes. The rest of the Jews lived in terror. Father had left the house one day and didn’t return. Hoping for the best, Mama had combed all the hospitals, but in vain. When she arrived to the police station, she was told, “Stop searching. You will never find him.”

The neighbors, acquaintances, people who had attended the prayer services in their home, all withdrew, afraid to have “May G‑d help that we should never learn how strong we are.” contact with them once Father was imprisoned. In the synagogue courtyard that Rosh Hashanah, the congregants had moved quickly past them, avoiding eye contact. Isolated, alone, as though struck with a contagious condition, no one had extended to them the age-old greeting of leshanah tovah. “Don’t cry,” Mama had said when she sensed the tremor in her daughter’s hand. “Better not to start the new year with tears; we want to have a sweet new year.”

Suddenly, in the hushed stillness of the night, a voice rang out. “Leshanah tovah tikaseiv veseichaseim . . .” It was Pinchas Grenitz, singing to the stars, leaping and twirling and dancing, as he appeared to be greeting the stars, showering them with his New Year blessings that they be inscribed for a good new year.

“See here, Batya. He’s talking to us,” Mama whispered to Batya. “Stars don’t need his greetings, he’s talking to us. He’s afraid of the KGB, but he means us.”

A nurse appeared and checked the oxygen tube that was hooked into Batya’s nose. “She’ll be all right,” Batya heard her telling her husband. She wanted to reach out to him, to calm him, but she lay listless, suspended between Mama, there, and her husband, here.

What were those words Mama had said? “For two years, when my husband disappeared inside a Russian prison and I didn’t know whether I was a widow or not, I never questioned why.”

One day Father had appeared. Just like that. It had been on Purim of 1953, two years after he vanished. G‑d had sent them the best mishloach manot in the world. But he looked terrible. Mama ran to call a doctor who hurried back with her. “How did you get here?” the doctor asked.

Father had shrugged as if to ask, what do you mean? “I walked,” he said.

“You what? Your shoulder’s broken, do you know?” A shadow of concern crossed his face. “Don’t you feel any pain?”

“I don’t know,” Father answered plaintively. “It seems that a person has more strength than he’s aware of. Der eibishter zul helfen mir zulen keinmuhl nisht vissen vi shtark mir zenen” (May G‑d help that we should never learn how strong we are).

Father related how, two years earlier, a car had pulled up beside him and the driver had asked for directions. “Come closer,” the driver had said, “I can’t hear you.” Suddenly the door had opened and a KGB officer pulled him inside. They sped to the prison, shoved him into a cell the size of a square meter, where he could either sit or lie with his feet up—for seven hundred days he was unable to straighten his legs.

“This morning,” Father told us, “I was taken out for interrogation. ‘Who comes to pray at your services? Who are your friends?’”

Father kept his lips sealed throughout the torture. “You will die,” they shrieked. “You will never leave here alive.”

Suddenly the officer pressed a lever and the floor panel beneath his feet dropped. Father plunged into a dark vacuum. From the fall and the shock, he lost consciousness. He didn’t know how long he remained that way.

“And then I was aware of the sun—the sun that I hadn’t seen for 700 days—warming me with its brilliant rays. I was outside of the prison walls. I began to walk. To my amazement, no one was stopping me. I got to the prison gate. The guard nodded his head to me. ‘When we’ll need you,’ he said, ‘we’ll call you.’”

Later Batya discovered that the night before Father was released, Stalin, who had prepared to launch a post-Holocaust holocaust of his own, had met with Soviet leaders to reveal his plans. In the early hours of March 1 (Purim), as Stalin’s rage reached a crescendo, he collapsed on the floor, suffering a massive stroke.

The Ache in Batya’s Heart

The day went by in the placid gloom that spreads its wings in hospital rooms. Even though Batya was out of danger, she was still under careful observation, the bleeping of the monitors keeping up its steady pace. Dusk began to settle, lights were switched on, dispelling the obscurity of the twilight. The overpowering weakness that had gripped Batya was beginning to dissipate.

I lived 91 years and never even became a grandmother, Mama’s words suddenly came to her. A sudden twinge of pain flashed through her chest. All her life, she’d dreamt of being a mother, of raising her children with love. Her arms yearned to cradle new life; her heart ached with the emptiness of a silent home. Almost on their own, her lips began to move, as she mouthed the words of old Jewish lullabies.

Her husband leaned slightly forward. “It’s okay, Batya. The danger has passed. Just relax, don’t exert yourself.” Batya felt like screaming at the top of her lungs, “I was given another chance,” but even whispering those words was too much for her. She allowed herself to sink back into her thoughts once again.

Father’s Last Request

Before Father’s passing, he’d invited her out for a walk near the river. “I have no sons, no one who will say kaddish for me. I ask of you, my dear daughter, you be my kaddish’l.” She could still see the water’s waves, the pigeons strutting around, pecking at crumbs. “Batya,” Father had said. “You know that I had sons. I taught them Torah. And now, I have no sons, no one who will say kaddish for me. I ask of you, my dear daughter, you be my kaddish’l. Follow the path of Torah and good deeds that I have laid out for you, and you will be my kaddish’l.”

“Why are you talking about death, Father?” Batya had protested. “You always said to serve G‑d with joy, always to see the glass half-full. Let’s enjoy what we have—the birds singing, the verdant grass, the crystal blue water, the flowers’ delicate scent. When you talk about death, it’s hard for me to be happy.”

“Batya’le, a person should not put things off for tomorrow,” he said. “No one is assured that he’ll have a tomorrow.”

Father passed away in his sleep that night, and she—she had greeted the morning as an orphan.

Batya sighed. The ethereal gossamer thread of life . . . how swiftly one can lose the grip on this precious gift called life. A tear fell out of her eye. Father, she remembered, had asked her to be his kaddish’l, to continue in his footsteps of Torah and good deeds. But who will be my kaddish’l? Who will continue the legacy of Father, of Mama, after I am gone? G‑d didn’t grant me any children. But now I was given a second chance. My visa to life has been extended. What mission did G‑d entrust me with?

Some time elapsed. Batya recuperated, “We weren’t blessed with children, but that doesn’t mean that we’re exempt from caring for children . . .” but the question followed her everywhere. What mission was she meant to fulfill? She turned to her husband for advice. “We weren’t blessed with children,” he said to her. “But that doesn’t mean that we’re exempt from caring for children . . . the burden of raising children belongs to everyone, whether you have children or not.”

Children? At her age? She was soon reaching retirement; life’s hectic pace would slow down. A leisurely cup of coffee in the morning in the coziness of her kitchen, without deadlines and meetings looming before her—a life of leisure beckoned to her. Where did children come in to that picture? What was her husband talking about? She didn’t even have grandchildren.

Retirement Indefinitely Postponed

The answer wasn’t long in coming. Three weeks later, Batya received a frantic phone call from her friend Esther. Esther, who had been a longtime principal in a school, had just been transferred to a different school. School was starting tomorrow.

“The board of education has decided to get rid of me,” her friend was talking in a choked voice. “This school is the last stop, everyone knows that. These children are disobedient and unruly, no one can handle them. Batya, I have a two-week-old baby, eleven mouths to feed . . . why are they doing this to me?”

“Calm down, Esther. Things will work out, you’ll see. I’ll be there for you. Esther, these children are troubled. We’ll help them; we’ll get to their hearts before we get to their minds.”

Having scaled the hills of suffering and privation, Batya stood at the summit of life—and enjoyed the panorama from a wise and experienced lookout point. Conventional wisdom dictated that it was time to indulge her weary bones with a cup of coffee every morning, to relax into the arms of old age. Instead, she inclined her ear and listened to the sounds of troubled hearts calling to her from the ravine below.

Batya paid a visit to the school were Esther was now employed. An experienced lecturer, Batya captivated students with her description of life in Russia. On that day, the children were ushered into the auditorium; a smiling Batya was stepping up to the podium, when suddenly, a little girl sidled up to her. “Before you start talking, can you put a sandwich in my pocket?”

Batya’s eyes opened wide. She looked at the girl—from the creased and stained uniform blouse to her shabby shoes, open laces snaking around them; a toe peeked out from the corner of her shoes. Batya’s eyes traveled up to the youngster’s pale face. Her cheeks were hollow, her eyes so filled with sadness, it tore at Batya’s heart. Here was a hungry child. And suddenly Batya’s eyes blurred. She saw herself standing in a tiny kitchen in Kiev, her mother pouring warm water over a kilo of bread. How hungry she herself had been as a child . . .

These children, she discovered, Here was a hungry child. And suddenly Batya saw herself standing in a tiny kitchen in Kiev. How hungry she herself had been as a child . . . were hungry not only for a piece of bread, but for a little sunshine too. When, after a long day at school, having left the house without food, these children returned to homes strewn with dirty laundry, sullied dishes and empty pots, they seldom saw their mother’s smile.

Batya couldn’t rest. She knew without a doubt that this was her mission, the reason why her “visa” was extended. These children needed someone to care.

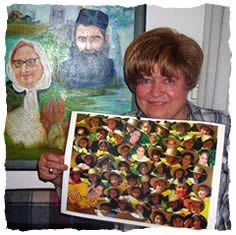

And care she does, to this very day. Batya established Mercaz Batya—Yam Hachesed in the Bucharan neighborhood of Jerusalem. This organization provides a daily afternoon program for 150 children from grades 1 to 8. To ensure that each child receives a warm meal to nourish their bodies, Batya traipses around the world to raise funds, and then hurries back to school so that she is there to give these children a smile, a kind word—to nourish their souls.

In addition to the meals, Batya also hires remedial help for those students who need such services, as well as qualified instructors to train the students in various crafts such as cuisine and dressmaking. She introduces them to music and to drama, and arranges performances so that each girl has a chance to star. Batya has devoted her life to these girls in every way.

She is, after all, her father’s kaddish’l.

Join the Discussion