It was 1951. Eighteen years old, newly married and expecting her first child, Miriam Fellig was alone. She had her husband, Joe (Yosef Mordechai) Fellig, but all her family had perished in the Holocaust. She traveled from her home in Montreal to meet the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—who had only recently assumed the leadership of Chabad-Lubavitch. She confided in the Rebbe, telling him about her dreams and fears. She wanted to have a large family, she told the Rebbe, but she had no family to help her. Would the Rebbe adopt her?

Without hesitation, the Rebbe answered in the affirmative, and thus began a decades-long relationship between a young mother and a leader of world Jewry.

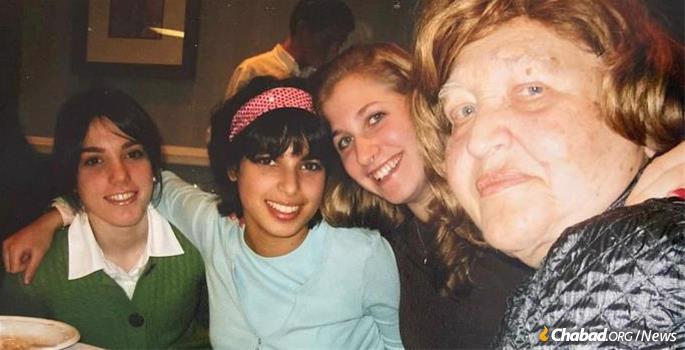

“I am going to have as many kids as I can because I will never talk about the Holocaust, but I have to do something about it,” Fellig, who passed away on Nov. 12 at the age of 89, told the USC Shoah Foundation in an interview, recalling her words to her newlywed husband. “And I am going to have a name for everyone in my family so they will never be forgotten, and I am going to have children that will want to have children. I am going to do to Hitler what he did to me. He took everything away, and I am going to bring it back. I am not going to just be defeated and talk about it, cry about it, light candles; I am going to have living monuments ... 10 months after [marriage], I had my first son.”

Born on Dec. 20, 1931, to Jacob and Hanna Goldwasser in Warsaw, Poland, Miriam was only a little girl when she began to feel the rising animosity towards the Jews.

Her mother was estranged from her family, after leaving observance and marrying Jacob, a non-religious young man she’d met at a party. Hanna spent a lot of time away from home partying, and young Miriam and her brother Yanush were often left in the care of their non-Jewish Polish nanny, Matushka.

When Hitler tore Miriam away from her family, it was Matushka who saved her life.

A Young Girl in the Warsaw Ghetto

After managing to escape Poland for Belarus, the family turned around, regretting that they’d left Jacob’s mother behind. But once they made it back to Warsaw, there was no going back. They were forced into the ghetto with all the other Jews, their erstwhile maids and servants spitting on them as they vacated their home.

While able-bodied Jews were sent off during the day for forced labor, Miriam stayed home in the ghetto with her maternal grandmother. One day, Nazis were going door to door. They burst into her home, killing Miriam’s grandmother. One Nazi went to the next home, telling his comrade to “finish the job.” The remaining Nazi looked at the little blonde girl with blue eyes and muttered something about Miriam reminding him of his own child. Patting her on the head, he shot a bullet at the ceiling and left.

From that point on, Miriam spent her days hiding under the apartment floor. She had a flashlight, some books and toys, and remained there until her parents came home from forced labor. They would move aside the table, roll up the rug and lift the trap door for her to emerge. Her only brother, Yanush, was shot while foraging for food to alleviate Miriam’s hunger.

A once-carefree childhood became a nightmare, and Miriam constantly worried that her loved ones would disappear, leaving her under the trap door.

In time, the family was rounded up on cattle cars and sent to a camp. There was no space at the camp, so they were sent back to the ghetto on a crammed, days-long journey.

Miriam’s maternal grandfather arranged for her to escape the ghetto under a truckful of soil, to the care of her Polish nanny, Matushka. She was 9 when she last saw her parents.

At great self-sacrifice, Matushka hid Miriam in her own home. Matushka’s sister reported her to the Gestapo, who brutally beat her. On her way there, she swallowed the numbers of Miriam’s parent’s Swiss bank account to hide the evidence. Miriam never recovered the money. It became too dangerous to keep her at home. Matushka put her in the care of a convent orphanage, warning the girl to never disclose her Jewishness.

A 15-Year-Old Orphan

At the war’s end, 15-year-old Miriam waited for her family to return. Nobody ever came. It turned out that her entire family was murdered. “You are a Jew, you must return to your people,” Matushka told her. Reluctantly, Miriam left Matushka for a Jewish orphanage in France.

The Jewish Agency discovered a third cousin in the United States, Leah Habergrutz, who agreed to sponsor her. The U.S. visa was rejected, and Miriam instead boarded a ship to Canada.

As soon as she arrived in Montreal, Miriam met her husband-to-be: Joe (Yosef Mordechai) Fellig, a refugee from Vienna, was waiting at the train station as he did frequently, finding ways to assist the new refugees.

She was taken in by a childless Montreal couple, and after realizing she wouldn’t fit in with the carefree Canadian teenagers in school, she went to work in a sewing factory. Joe Fellig waited two years, and then asked Miriam for her hand in marriage, on condition she would have an observant home.

“She loved being frum (‘observant’),” says her daughter, Goldie Tennenhaus. “My mother had a real relationship with G‑d. When I asked her how she became observant after the war, she simply said, ‘I saw what He can do; I knew I had to listen.’ ”

Joe taught her the practical ins-and-out of keeping an observant home, and she was a keen learner. “She learned by watching,” adds Tennenhaus.

At her engagement party, she overheard one of her fiancé’s friends asking him, “How do you know the Germans didn’t do something to her? Maybe she won’t be able to have children?” Miriam Fellig soon proved him wrong, bearing 10 children.

Turning to the Rebbe

With no parents, aunts or uncles, the Rebbe was the only person Miriam had to show her children off to. Every year, the family would drive from Montreal to Brooklyn and proudly present the children to the Rebbe. As the family grew, Miriam expressed her concern to the Rebbe that it would be difficult to find a place to stay the next year, and she didn’t know if they’d be able to come back. “The Rebbe sent his secretary, Rabbi Binyamin Klein, to look for my father,” Tennenhaus recalled. Klein gave him the keys to a large house next to 770 Eastern Parkway, Chabad-Lubavitch headquarters.

The Rebbe listened to her worries, fears and challenges, and counseled her as a parent would. “Be a warrior, not a worrier,” the Rebbe told Miriam in a private audience, her daughter wrote in the N’shei Chabad Newsletter. When she told the Rebbe that no matter how hard she tried, she couldn’t keep her house neat and tidy with her growing young brood, the Rebbe gently replied, “But I see your husband, and he looks happy.”

It was the Rebbe’s fatherly guidance and care that helped Miriam cope with the loss of her entire family. “She would ask the Rebbe whatever she wanted,” says Tennenhaus. “How do you still thank G‑d after you lost everything?” a granddaughter once asked her. Miriam replied that it was the Rebbe’s love for her that got her through it.

But the trauma that little girl in Warsaw experienced never went away completely. She kept her family close, still scarred by her losses. “She once remarked to the Rebbe that she feels safest in the car with her entire family,” says Tennenhaus. The small confines of the car, with her family surrounding her allowed her to feel secure, Tennenhaus explains. That devotion to her family and her connection with the Rebbe helped her secure a signed letter from the Rebbe in honor of her son–in-law’s and daughter's new Chabad center in Hallandale, Fla. “The Rebbe’s secretariat told us that the Rebbe wasn’t sending personalized letters anymore for these occasions,” notes Tennenhaus, but her mother persisted. “My son-in-law works so hard,” she told the Rebbe’s secretary Rabbi Binyamin Klein. “Maybe the Rebbe can send us a letter?” Beginning in 1985, they received personalized letters for their annual dinners from the Rebbe. The last letter they received, in 1992, was in fact the last letter the Rebbe signed—the secretariat later informed Tennenhaus—just hours before he suffered a major stroke while visiting his father-in-law and predecessor's graveside in Queens.

Her trademark dry wittiness helped her diffuse difficult situations with a touch of humor. Goldie Tennenhaus recalls a grandson once lashing out, asking why he needed to keep kosher. “McDonald’s or Wendy’s?” Miriam responded. “She let you be yourself,” says Tennenhaus, noting that her mother kept an open home for all—from yeshivah students to teenage grandchildren looking for a break.

“My mother showed us how to fiercely love, protect and fight for our spouse and family. She taught her children and grandchildren to believe in G‑d, to hold the Torah dear, and to love the Rebbe and trust in his words.”

Miriam Fellig was predeceased by her husband, Joe (Yosef Mordechai), in 1991, and by their daughter, Itty Ainsworth, who tragically died together with her husband, Tzvi, in the June 2021 condominium collapse in Surfside, Fla.

She was also predeceased by grandchildren Elisha Fellig and Tzviky Fellig.

She is survived by her children: Rabbi Yaakov Fellig (Coconut Grove, Fla.); Hershey Fellig (Montreal); Chana Silverman (Hallandale, Fla.); Mendy Fellig (Miami); Goldie Tennenhaus (Hallandale, Fla.); Shulamith Lurie (Hallandale, Fla.); Shneur Zalman Fellig (Miami); Shlomo Fellig (Miami); Ouli Fellig (Miami); in addition to many grandchildren, great-grandchildren and a great-great-grandchild.

Join the Discussion