It was during the morning prayers, one day in September of 1939, when bombs started falling on the resort town of Otwock, Poland. War had arrived to this country whose government had declared that there was no need for its citizens to be prepared for conflict—because, the government asserted, the Germans would fail in any attack on Poland.

The bombs from the German fighters hit the town’s Jewish orphanage. The townsfolk understood the message: Jewish lives are worthless. Innocent child or saintly sage, everyone was a target, everyone would be murdered—or so the Nazis intended.

On the town’s streets, chaos ensued; no one knew where to go, what to do. The students of the Tomchei Tmimim Lubavitch school were no different. They burrowed their way into holes they dug in the ground. But when the falling bombs began creating gaping craters, they realized that it was a futile endeavor.

The students wanted to flee. But it did not make sense for the students to return home; that would mean traveling further into Poland, and closer to Germany.

Many of the students, in small groups, began to trek towards Russia, with only their ritual phylacteries, tefillin, in hand. Chaim Meir Bukiet joined one of these groups, hoping to find transport to the Soviet country in a nearby town.

The students arrived in a small town late on Friday afternoon. The locals advised them to continue on their way to a larger city, where they would have a better chance of finding transport. They continued on their way to the larger city, praying the evening Shabbat services upon their arrival. When there, too, they could not find any transport, they continued on their way, walking through the night. (During a time of danger, disregarding the laws of the holy Shabbat by traveling is not only permitted; it is a divine edict.)

Dead bodies were strewn along the roads, and huge fires raged nearby. The roads were illuminated as if it was midday. And they soon reconsidered their plan, realizing that a Jew in sight of the German fighter jets above was a target. The students backtracked to the school in Otwock, to make further plans from there.

By the time the students arrived, the Polish townspeople had emptied the school of all of its contents. But the students remained in the town for the High Holidays and the holiday of Sukkot.

Life Under German Rule

The students discussed among themselves what they should do next. Warsaw was being bombed by the Germans, and most of the city was in shambles. Russia seemed to be out of reach. So they decided to return to their respective homes.

Chaim Meir began his trip home to Chmielnik by walking to the closest train station, but quickly realized that it would be way too dangerous for him to go by train. So, he continued on foot. Occasionally during his long trek home, a kind man would take pity on him and give him a ride on his wagon for a short distance. After a long week, Chaim Meir arrived at the home of his dear parents, Rochel and Avraham Shmuel.

Chaim Meir had been lovingly raised in Chmielnik as an only child. His father would import grain from his parents’ farm in Wislica. Rochel had a small store where she would sell basic food items.

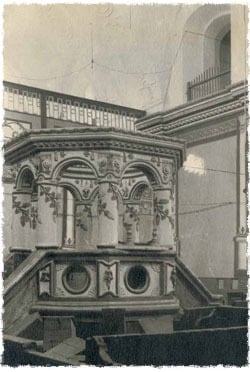

Chaim Meir had wonderful childhood memories of Shabbat in his hometown. Locals would flock to the many synagogues, with the central Chmielniker Synagogue overflowing each week. Townspeople would calmly stroll through the town after their Shabbat meals; stores were shuttered, and a peaceful aura reigned.

But now the Germans had taken charge. Their first murder was on Pinezowska Street, just a few short blocks from Chaim Meir’s home. A curfew was in effect, and random killings were commonplace.

Chmielnik was a small town with some twelve thousand citizens, ten thousand of whom were Jews. As such, Chmielnik had now become a “safe” haven for Jews who lived in nearby towns where they were a minority. In those towns, many of the Polish citizens joined the Nazis, unleashing years of pent-up hatred on their Jewish neighbors.

The local Chmielnik Jews took in thousands of refugees, and the Bukiets were no different. By the time Chaim Meir arrived, his parents had moved up to the attic, giving their beds to refugees from the city of Płock. They treated their guests as family, caring for their needs despite the harsh circumstances, and sharing their meager provisions.

The young teenager witnessed the Germans forcing his learned father to clean the streets of the town, and tormenting his mother, stripping her of her livelihood.

Messages from “Grandfather”

The Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, then in Warsaw, instructed all the Lubavitch students in the city to find a way to go to Vilnius, Lithuania. He supplied the funds for the students to travel, and instructed them to convince everyone they knew to go to Vilnius too.

The Russians had just granted Lithuania self-rule, creating the only democracy in the region. At this time, all Jews in Lithuania were safe from both the Russians, who were sending Jews to Siberia, and the Germans.

The Lubavitch students who arrived safely in Vilnius immediately began sending letters to all their friends and acquaintances.

It was on the holiday of Chanukah that a letter arrived in Chmielnik, written on onion-skin paper. It described various ways to escape from Poland to Lithuania via Russia. Rochel gave the letter to the addressee, her son.

When she learned of the contents of the letter, Rochel, shaking violently, told her son that the letter was surely written by irresponsible students. It could not be that the Rebbe truly instructed his students to go to Vilnius. “Why would someone send such instructions while we are under German rule, placing our entire family in great danger?” she exclaimed. “It is dangerous for us to even keep this letter in our home!”

Meanwhile, the Rebbe—who had arrived in Riga, Latvia, shortly after Chanukah—persisted in his request that the students contact their friends. He sent another plea to his students: “Surely you have written to your friends—students like yourself—in whatever place they may be, encouraging them to hastily join you. May no obstacle or impediment stop them!”

So, they continued sending letters. They kept lists of whom they had sent letters to, regularly updating the Rebbe.

Telegrams and letters began arriving for Chaim Meir, reiterating that the Rebbe urged everyone to come to Vilnius immediately.

These messages were all coded, referring to the Rebbe as Chaim Meir’s “grandfather” who wished that he would come to him. Other messages included hints to go to Vilnius. “Go to Feivel, the one who blows the shofar on the High Holidays, and Anschel Aronovitch”—two individuals known to reside in Vilnius.

Rochel, though, still had her doubts. She asked a local rabbi whether they should permit their son to leave to Vilnius. The rabbi said that the roads are dangerous—he knew this from his son who had traveled there—and if only the senders of the letters were aware of the dangers, they would cease sending them. At Rochel’s request, the rabbi wrote down his opinion, and she brought it to her son.

As the weeks and days moved along, life under the Germans became more and more difficult. Chaim Meir, however, aware of his mother’s great love for him as an only child, was reluctant to disrespect her wish. Though anxious to leave, he would do so only with her consent.

In January 1940, a letter arrived from Yosef Rodal. In a coded message, he too informed Chaim Meir of the Rebbe’s wish that he should come to Vilnius.

Yosef had assisted Chaim Meir in a time of need during his stay at the school in Otwock. Chaim Meir, being an only child, was not used to the school’s bare accommodations, and out of despair had resolved to return home. Seeing the sad look on the young lad’s face, Yosef had invited him to stay with him. Chaim Meir now recounted to his mother the care that Yosef had given him, and how the older student had gone to find a mattress for him, schlepping it across the small town so that he would be comfortable. Surely Yosef had only his best interests at heart.

Teary-eyed, Rochel agreed to let her son depart to Lithuania. While she did not have the strength to go along, she wanted her husband, Avraham Shmuel, to go with their son. They gathered some personal belongings and readied to depart.

Rochel hugged her only child, with the knowledge that this could be the last time she would see him for a long time. As they were leaving, she gave him her most precious possession, her wedding ring. “If you find yourself in dire need, use this to bail yourself out,” she said.

Chaim Meir was deeply torn. He knew that he was following the right path; departing from his mother, however, when there was no telling what tomorrow would bring, tore his heart to shreds.

Trekking in the Cold

In a heavy snowfall and gusty winds, father and son traveled by horse and wagon towards the town of Kielce. At times they were forced to push the wagon themselves in the knee-deep snow. They arrived after more than twelve hours—a trip that usually took a half-hour.

The next morning, the father told his son that he could not continue in these conditions. Chaim Meir, steadfast in his resolve to follow the Rebbe’s directive, embraced his father and took leave of him. He did not know when he would see his father again.

Chaim Meir arrived in Warsaw. There he saw the atrocities perpetrated against the Jewish community by the SS officers. He headed out of Warsaw with funds provided by a Lubavitch chassid at the Rebbe’s instructions. The funds would be enough to pay someone to smuggle him across the Polish-Russian border.

On the way, he encountered thousands of refugees returning from Russia. They told him that the Russians were exiling all the Jewish refugees to Siberia. In their estimation, living in Siberia was worse than living under German rule. They could not fathom why he was going there . . .

Chaim Meir crossed the border and trekked through Russia, from town to town. The kind Jewish locals supplied him with food and funds to continue on his way. He lodged in synagogues, or in the homes of kind Jews who risked their lives to host him.

On the festive holiday of Purim, when Jews across the globe celebrate the salvation from Haman’s decree to annihilate the Jewish nation, Chaim Meir met up with Lubavitch disciples, and they celebrated the holiday with a farbrengen, a gathering of souls.

“When Russia turned communist,” an elderly disciple, or chassid, told those sitting around the table, “at a Purim gathering with Rabbi Sholom DovBer of Lubavitch, someone said that communism cannot last for long, because it represents war against G‑d.

“The Rebbe responded, ‘G‑d can tolerate when someone wages war against Him or against religion. When someone wages war against the Jewish body, however—that G‑d cannot tolerate. That cannot last.’”

The words gave Chaim Meir strength; he understood that the Nazi threat would eventually vanish. He continued on his tiring journey.

Arriving at the Lubavitch school in Vilnius, he found an atmosphere of Torah study. Once again, he was with his friends.

War Connections

On July 21, 1940, the USSR reoccupied Latvia. Vilnius was a safe haven for the Jews no longer.

The kindhearted Japanese consul in Kovno, Chiune Sugihara, granted the students transit visas to Japan. The students traveled through Russia for twelve days, until they reached Vladivostok, from where they would take a boat to Japan.

Chaim Meir never stopped thinking about his parents. Upon arriving in Vladivostok, he purchased coffee and some other basic items that he knew they would appreciate, and sent these items to them. He also wrote a note telling them that he was well and en route to Kobe, Japan.

The students arrived in Kobe in late August of 1941. They were greeted warmly by the Jewish community.

The Bukiets made every effort to contact their only child. They were relentless and creative in their efforts.

The first letter that reached their son was addressed to the Jewish community of Kobe. The Japanese, who were extremely polite and kind to the new refugees, turned the letter over to the Jewish community, who in turn located Chaim Meir amongst the thousands of refugees.

The parents’ messages, in German, wished that they should all survive the atrocities and once again be united. In coded language, the parents wrote the return address city as Chamy Yanik—in Hebrew, “G‑d should have pity on the child”—instead of Chmielnik.

The letters were filled with concern about their son, never making mention of their own horrendous situation. Their pain at not being able to be with their child seethed through the short letters.

In mid-October of 1941, as they prepared to attack Pearl Harbor, the Japanese felt that it was time for the refugees to leave their country. The only option for the Jews was to go to Shanghai, China, an international city that welcomed everyone.

It was at this point that Chaim Meir’s parents lost contact with him. Months passed, and they did not hear from him. They worried that the worst had happened to him. There was no end to their pain.

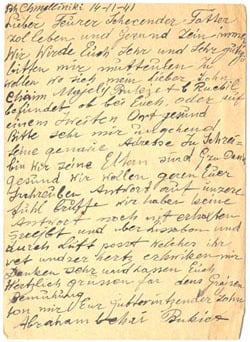

They tried to reach the Rebbe, who had arrived in New York on March 19, 1940, but initially met with no success. On December 14, 1941, however, the parents sent a letter that did eventually reach the Rebbe, though there were many mistakes in the address. The parents wrote the letter in broken German, interspersed with many Yiddish terms, as if they were writing a letter to their father:

Dear, beloved and highly-esteemed father, may you live and always be healthy,

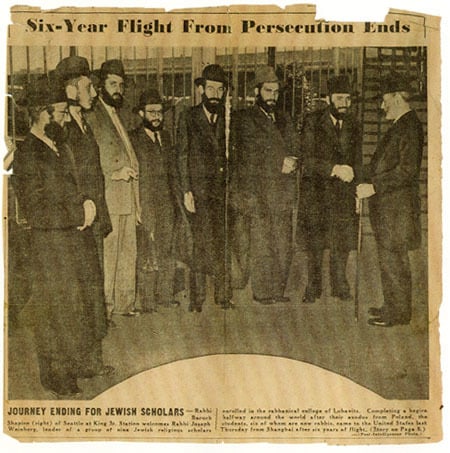

The back of the postcard. (Courtesy of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Library)

The back of the postcard. (Courtesy of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Library)We would very much appreciate if you would be so kind as to share with us the whereabouts of our dear son, Chaim Meir Bukiet the son of Rochel. Is he with you, healthy, or is he in another location?

If you could, please expeditiously inform us of his exact address where we can write to him. We, his parents, are healthy, thank G‑d. We would like your answer to our many letters—to which thus far we have not received any response. Write us via Lisbon airmail, and you will gladden our hearts. We thank you deeply for the effort.

From your children, Avraham Shmuel and Rochel Bukiet

A week before they sent this letter, on December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, forcing the United States to enter the war.

On that very same day, the Japanese occupied Shanghai, placing the Jewish refugees once again under Japanese rule, and in effect sealing off the students’ connection with the Rebbe in the United States.

A Man in Scheveningen

Life in Chmielnik became a living hell, as the Germans issued ever-harsher restrictions and edicts against the Jews, making their life unlivable. The Jews were herded into a ghetto; many began dying from hunger.

Jews were also banned from listening to the radio, and had no clue of what was going on in Germany and the rest of Poland. Slowly, however, the Bukiets learned through the grapevine of the atrocities the Nazis were committing; they began to fathom what their likely fate would be.

When Jews would set out to escape Chmielnik, the Bukiets begged them to promise that if they ever made it to the United States, they would send regards to their son Chaim Meir, who would surely be with the Rebbe there. They had a picture taken of themselves and sent it to New York, with the hope that it would reach their son if he ever made it there.

In Shanghai, meanwhile, Chaim Meir and his friends, too hot to sit in their wool clothes, spent their days in the hot city studying in their pajamas. They would listen to the news coming from Europe, and discussed the fate of their parents and relatives, wondering whether they would ever hear from them again.

In Schevenigen, Netherlands, a Polish native named Moshe Stiel had become sort of a middleman between Jews in Poland and their relatives elsewhere. Together with his wife, Bertha, he resided with several hundred Jewish families in this town near The Hague.

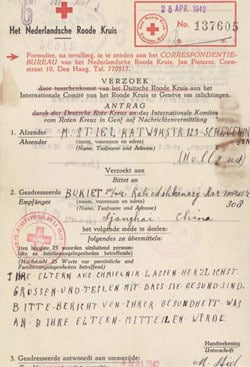

The Bukiets in Chmielnik found a way to get in touch with Moshe, asking him to relay a message to their son, who they thought to be somewhere in Asia. On April 25th, 1942, Moshe traveled to the Red Cross office in the The Hague, where the Red Cross facilitated sending messages, via Switzerland, at no charge, to war refugees across the globe.

Your parents from Chmielnik send heartfelt greetings, and they tell you that the news of the health of your parents should be spread.

M. Stiel

Almost three months later, on July 19, 1942, the communication reached Chaim Meir in Shanghai. Chaim Meir was obviously overjoyed at the news that his parents were still alive amidst all the atrocities.

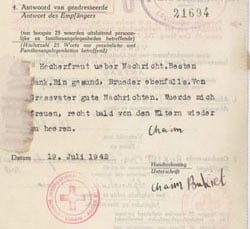

Chaim Meir responded, with a typed message in German on the other side of the telegram.

Delighted about the news. Thank you. I’m healthy, my brothers [fellow students], too. From Grandfather [the Rebbe], good news. Would be glad to hear from my parents very soon once again.

Chaim Bukiet

The telegram arrived to The Hague on November 26, 1942, and was sent to Moshe in Scheveningen. But by the time it arrived to the Stiels’ home, they were already en route to the Westerbork concentration camp, where they arrived on December 5, 1942. The Red Cross forwarded the telegram there, but by the time it arrived, he and his wife were in the midst of being transported to Auschwitz, where they arrived on February 23, 1943.

The Red Cross sent the telegram back to Shanghai, but by the time it arrived, the Japanese had forced most of the Jewish refugees into a ghetto, and the Red Cross could not find Chaim Meir.

The telegram was returned to the Red Cross in The Hague, where it joined close to a dozen returned telegrams to Jews in the vicinity of The Hague who had been deported.

The Boat to the United States

The students gathered around the radio to listen to the emperor Hirohito’s speech wherein he unconditionally surrendered to the Americans—they had picked up a little bit of Japanese. They were overjoyed at his announcement that the war was over.

At Lubavitch World Headquarters, chassidim worked on obtaining student visas for the group. A year later, the students traveled to the United States; on July 17, 1946, they arrived in S. Francisco. When Chaim Meir arrived in New York, he was 25 years old.

Upon arriving, he was greeted with the letter his parents had sent to the Rebbe.

His already broken heart was further decimated . . .

His parents had been painfully trying to reach him the entire time he was in Shanghai . . .

For months upon months, they had not been able to make contact with him. Had he made the right decision to depart from them? What ever happened to them? Would he ever see them again?

During his free time, Chaim Meir would stand on the street corners where the Red Cross posted the names of survivors, scouring the lists, searching for his parents’ names. Each time he left the corner after another futile search, memories of his departure from his parents resurfaced, along with renewed pain.

He treasured the picture his parents had sent him, the picture that they took especially for him. It was his last kiss from them; he sensed in it their deep love for him.

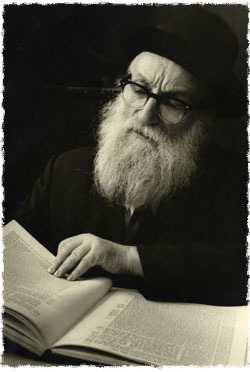

A scholar of note, Chaim Meir took charge of the younger students at Lubavitch World Headquarters. He started delivering deep lectures on Talmudic concepts, and would often discuss scholarly topics with Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the son-in-law of the Rebbe and the one in charge of the Lubavitch publishing house, as well as the movement’s educational and social activities.

In 1947, Chaim Meir traveled to Uruguay to meet a young woman named Esther. Esther had immigrated from Wislica, Poland, to Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1928. Chaim Meir and Esther married several months later. Shortly thereafter the young couple relocated to New York, where Esther gave birth to their first child.

The Ashkenazic custom is not to name a child after a living individual. With no information yet as to his parents’ fate, Chaim Meir asked the Rebbe whether they should name the newborn child after his mother. The Rebbe responded in the affirmative. She was named Rochel.

It was then that Chaim Meir knew that she had died at the hands of the Nazis.

Chaim Meir, like his parents before him, made his children the center of his life. He dedicated his life to making them happy.

He never spoke of the deep pain tucked away in his heart, about the great loss and pain he felt because he had left his parents behind. Seldom did he talk about the atrocities he witnessed during the war. Only on the holiday of Purim would he tell of the miracles he experienced when he escaped from Poland to Russia to Lithuania.

Dancing to the Hora at UCLA

Shabbat after Shabbat in the early 1970s, sounds of biblical verses and hymns, led by a young rabbi with a booming voice, brought more than 100 students to their feet. The singing was the highlight of the night at the Chabad-Lubavitch center at UCLA.

Rabbi Yerachmiel and Rochel (“Ruchie”) Stillman—a couple about the same age as the students they were servicing—had joined Rabbi Baruch Shlomo and Miriam Cunin at this first Chabad House established on a college campus.

Jewish students would flock to the center in search of meaning. Together with Rabbi Shlomo Schwartz, Yerachmiel would dance and sing with the crowd for hours. The girls danced in circles on one side of the partition, the boys on the other.

Following the uplifting prayer services, the students would go upstairs for the Shabbat meal. They would sing the song welcoming the Shabbat angels, partake of the traditional Shabbat foods, and listen to chassidic tales and words of Torah wisdom. Many would remain after the Grace After Meals and join the discussions that lasted until the wee hours of the morning.

Many students had not been inspired by their previous experiences with Judaism. Now they were hooked on these dynamic Shabbat services. They made the Chabad center their second home. Some students changed their lives dramatically, but all came away with more awareness of their Jewish heritage.

Ruchie Stillman, the daughter of Rabbi Chaim Meir, the namesake of his mother, Rochel, soon took over the reins of the center, becoming its backbone and chief coordinator. She would regularly confer with her parents in New York. Their insight had shaped her outlook on life; now she always looked to them for inspiration and guidance in her new position.

Undoubtedly, living on opposite ends of the country with limited communication was a difficult transition for both the firstborn daughter and her parents.

The Train to California

For many years, the Bukiet family had spent the summer months with Rabbi Bukiet’s school at Camp Gan Israel in the Catskills. There, Rabbi Chaim Meir would continue to mentor his students and deliver his Talmudic lectures.

Shortly after the Stillmans arrived in California, Ruchie learned that her father’s school would not be going to the Catskills that year. Rabbi Chaim Meir, who was known never to waste time, and also for his phenomenal dedication to teaching, wondered what he would do the entire summer. Ruchie immediately told her father that this was a great opportunity for her father, mother and siblings to come visit her in Westwood for the summer.

He did not like the idea. After a lengthy discussion, father and daughter decided to ask the advice of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who had some twenty years earlier succeeded his father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn.

The next day Ruchie got a call; Rabbi Chaim Meir was emotional and shaken as he relayed the Rebbe’s response: “I will mention you at the resting place [of my father-in-law, for a blessing].” The Rebbe then added two words in Hebrew: “It’s worthwhile [for you to travel to California].”

“This is monumental,” Rabbi Chaim Meir told his daughter. “I have a gut feeling that this response means that the trip will hold great meaning for me.”

Ruchie jokingly responded, “Of course it will have great meaning; you will be visiting your daughter in California!” But her father’s mindset at the moment didn’t allow for chitchat.

Ruchie explained that his visit would benefit the many students who come to the Chabad House at all hours, seeking spirituality. She knew that her father welcomed people from all backgrounds into his home, and that he had a knack for communicating with all sorts of people in their language. “You will have a chance to meet and influence hundreds of campus students at the Chabad House,” she said.

“I would do that wherever I would be,” he said. “I do not need to be in California to do that . . .” Rabbi Chaim Meir was not convinced that that was the reason why the Rebbe felt that it was “worthwhile” for him to go. For her part, Ruchie gave up trying to convince her father to see things her way. The bottom line is that he was coming.

Flying to California with four children was prohibitively expensive, so the Bukiets made plans to go by rail. They left from Manhattan, retracing the route that Rabbi Chaim Meir had taken years ago when he arrived from China.

The train ride was a disaster. It consisted of chasing four rowdy children, feeding them, dressing them, and listening to incessant nagging for another Coke from the food car. By the time they arrived in Los Angeles on Thursday afternoon, the rabbi and his wife were utterly exhausted, with the patriarch of the family not looking too well.

As it looked like the couple needed a long rest, Ruchie decided to postpone the plans for her father to spend time at the Chabad House, speaking with the students. Ruchie offered to make that week’s Friday night Shabbat meal at their home instead of at the center.“It is too much for you to walk up and down the hills of Westwood,” she explained.

Rabbi Chaim Meir, however, was adamant that his daughter not change the plans for him to spend time with the students. “I did not come here to change scheduled plans at the Chabad House!”

“That’s fine,” Ruchie responded, “I’ll make the food. You’ll eat the meal at home, and we’ll take the children to the Chabad House for the meal.”

“Did I come here to stay at home? Of course I want to be with the students at the Chabad House!” Rabbi Bukiet responded.

The Language Man

The sun set on Gayley Avenue overlooking the UCLA campus. Students piled in and casually greeted the young Chabad emissaries. That night, however, something was different. There was an elderly man, with a distinguished appearance and neatly rounded beard. His smile was loving, contagious and disarming.

The crowd danced that night, like every Shabbat, with palpable joy. As for Rabbi Chaim Meir, he danced along vigorously, as if the train ride had never happened.

After the electrifying prayer services, the crowd gathered around the Shabbat table. Rabbi Chaim Meir did not want to sit at the head of the table; he wanted to sit among the crowd of students. His wife, Esther, found a space for him to sit next to a young student.

The students waited for the elderly rabbi to speak to them. He did speak, a lot. He thought he was speaking in English, but he kept lapsing into Yiddish. The crowd, transfixed by his enthusiasm and passion, caught the gist of his words—they did not understand more than the general idea.

Teddy Kwasman, or Tuvia, as they called him in the Chabad House, did understand everything the rabbi was saying. He had learned Yiddish from his late grandfather, Chaim Lazar Rutkavetsky.

Tuvia had been one of the first students to become a regular at the weekly Friday night prayer services and Shabbat meal. In fact, this was going to be his last Shabbat at UCLA. He was preparing to receive an award from a Native American tribe for his fluency in their ancient tongue (he specialized in extinct languages). The next Shabbat he was going to spend with his family, and from there he was going to Germany to continue his studies.

In Rabbi Chaim Meir’s native tongue, Tuvia struck up conversation with him. The rabbi was amazed to find a young college student conversing with him in Yiddish.

Tuvia asked Rabbi Chaim Meir where he was from. “I am from a place you’ve never heard of,” he answered. “It’s a small town called Chmielnik.”

“Chmielnik,” responded Tuvia. “I know that town . . .”

The Expert on Chmielnik

Chaim Lazar Rutkavetsky had immigrated to the United States in 1913. Chaim Lazar’s father, a soldier in the czarist army, had been stationed in Chmielnik and married a local, Tuvia’s grandmother.

Tuvia spent many hours with his grandfather, who described to him in great detail the town, the people who lived there and its history. Tuvia was a sponge; once he heard something, he never forgot it. He described to the stunned rabbi the town he had grown up in, down to the very last detail.

Tuvia’s fascination with the town had led to his involvement with the Chmielnik Society. The society was mostly comprised of elderly Chmielnik natives who had emigrated before 1940. From across the globe, they would gather to discuss and reminisce about their town of old. They had a newsletter, and even published a book to remember their beloved town and its Jewish citizens.

For the rest of the evening, the two discussed the town, evoking memories from Rabbi Chaim Meir’s childhood. The beauty of Shabbat in the town was at the center of the discussion; it always was, in a discussion of Chmielnik.

Rabbi Bukiet confided to Tuvia the thoughts that constantly haunted him: Did his mother die in anguish because her son was not at her side? Did she feel to her very last moment that he had abandoned her?

“You know something,” Tuvia said, “there is a Chmielnik Society meeting this week. Maybe someone who knew your parents will be there.”

Rabbi Bukiet was eager for every opportunity to meet someone from Chmielnik. Maybe he’d meet someone who knew his parents’ final fate. Maybe someone could give him information about their lives during the years that he was in Asia. Maybe, maybe . . . “Where can I reach you?” Tuvia asked. “What is your daughter’s telephone number?”

The rabbi, thinking that Tuvia wanted to write down the number, shuddered at the thought that someone would desecrate the Shabbat in order to do something for him. He told Tuvia firmly that he would not give him the number because it was Shabbat—despite the fact that this refusal could mean giving up on an opportunity to meet someone who had information about his parents.

Tuvia told Rabbi Bukiet not to worry. “Rabbi, I know many languages by heart. I described your town to you as though I lived there for many years myself—do you think I cannot memorize your daughter’s phone number?”

Reassured, he gave Tuvia the number.

The two went to the Chmielnik Society meeting, where Rabbi Chaim Meir was greeted as the grandson of Chaim the ritual slaughterer. Rabbi Chaim Meir had never known his grandfather, after whom he was named, and he was delighted to meet those who had known him personally.

Some of the elders knew his mother, and identified his home as “Pinezowska, near the pump.” The mostly elderly crowd invited Rabbi Chaim Meir to address the meeting.

The bearded rabbi, who reminded the assembled of how their parents had appeared, told the crowd of the great pain he experienced during the Holocaust. He described his own rehabilitation through Jewish teachings.

Tears were falling on many faces as the assembled listened to the orphan, who now had a growing family of his own in the land of opportunity and assimilation.

“We need to let G‑d into our lives,” he said, choking on tears. “By adding light into the world, with one divine precept—one mitzvah—at a time, we need to let G‑d into our lives. We need to connect to our parents, their ways, what they stood for, even though we are far away from our hometown in this country of freedom.”

The crowd was very moved, and word got around, in the close-knit world of Chmielnik natives, of Chaim the ritual slaughterer’s grandson’s appearance at the Society’s meeting.

The Partisan

“This is Rochel from Chmielnik,” the caller told Ruchie Stillman. “I would like to meet the rabbi from Chmielnik.”

It was Rochel Scheiber, whom Rabbi Chaim Meir remembered as an intimate friend of his mother. Ruchie offered to pick her up and bring her to her home. The woman refused her offer. “Let’s meet in a place where no one needs to do anything special for me,” she said, adding that she had her own car. They agreed that the meeting would take place in the Chabad House.

Rabbi Chaim Meir, looking forward to the meeting as an honor and a matter of great importance, dressed his young children in their finest clothing, and went to the Chabad House.

Rochel Scheiber, a feisty and energetic woman, entered with cane in hand. She had been a member of a Jewish group of partisans that had fought the German army from the forests. The mark of a bullet hole was visible in her neck. She was a fighter, and to those just meeting her it looked as if she was responsible for the death of many Nazi soldiers.

Rochel had been a good friend of Rochel Bukiet. She had held the young Chaim Meir as a small child, and watched him grow up. She knew the great love the mother and son had for each other.

“They came three times to round up the Jews of Chmielnik,” Rochel said to those gathered to meet her. “The first time, they rounded up many of the community leaders and Torah scrolls, locked them in one of the study halls, and burnt the building. That was their announcement that they had arrived.

“My husband, daughter and I were in the same train car as Rochel and Avraham Shmuel on the way to the Treblinka concentration camp. People were dyeing like flies; we were treated worse than animals.”

Rochel said that she noticed that on turns, the train would slow down. “I told my friend Rochel that the next time it slows down, we are going to jump out of the window. She told me, ‘I have no strength; how will I jump out, hide in forests, and be always on the run?’

“Hours later, the train slowed down as it turned a corner. I told Rochel, ‘I am going to jump.’

“Rochel spun me around to look straight into my eyes and said, ‘If you ever meet Chaim Meir, tell him I left a remembrance on this world.’”

Rabbi Chaim Meir said nothing. It was apparent that he was digesting the message. His mother had left a remembrance in the world. He was the remembrance.

In her final moments, his mother wasn’t upset that he had left her. She was glad to leave behind an eternal remembrance and legacy.

Rabbi Chaim Meir escorted Rochel to the door solemnly. Leaving the Chabad House, his face was that of a changed person, a son with intimate knowledge of his mother’s last message to him. It was a message of love and assurance that his success in this world is of utmost importance to his parents.

Join the Discussion