Avraham Aharon Rubashkin was from Nevel—that legendary Chassidic White Russian town—just like his parents and their parents before them.

It was as a boy in Nevel that, in 1938, the Soviets forcibly closed down his cheder. From there he fled, together with his family, amid Nazi bombs and roadside strafing, surviving the war thousands of miles away. He escaped the Soviet Union in 1946, never to return. In the early 1950s, Rubashkin arrived in New York City, opening a modest kosher butchery in Brooklyn that would eventually grow into the world’s largest kosher meat and poultry slaughterhouse and supplier and with which his name would become synonymous.

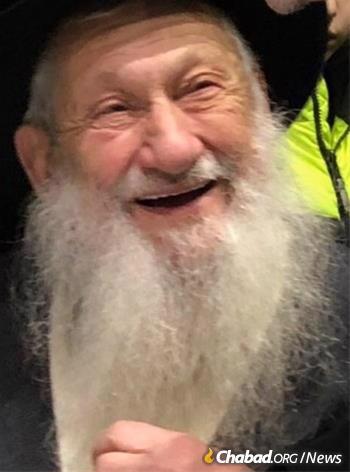

Yet it was to Nevel that Rubashkin—who passed away on April 2 at age 92 from complications due to COVID-19—always returned, the town of his youth forever remaining a byword for vivid, joyful Jewish life and authentic brotherly love.

Throughout the ups and downs of his life, he’d constantly retell the stories he had heard as a boy and recall the town’s simple heroes, always learning from their example.

One he liked to tell was the story of his great-grandfather, Mendel, who for health reasons had to spend time in the countryside. Of course, they still needed to support the family, so early each morning Mendel’s wife would milk the family’s cow and head into Nevel to sell the milk door to door. One morning she fell ill so Mendel went instead. When he returned, his wife counted the proceeds only to discover it all amounted to a few kopeks, not nearly what the milk was worth.

“The first house I came to was well-off, and the housewife said she has her own cow and doesn’t need my milk,” came the patriarch’s response. “The second house needed milk, but didn’t have enough money to pay for it, so I gave it to her anyway.” Those who didn’t want his milk, he realized, didn’t need it, while those who did couldn’t afford it. So he distributed all his milk for a few kopeks.

For Mendel’s descendent, Avraham Aharon, this story would become a motto for life. One had to give to others not for recognition or plaques, but because there were people out there who needed help.

“This was the ‘milk’ children grew up on in Nevel,” Rubashkin said of their education.

“That’s exactly how he lived his whole life,” said his grandson, Yossi Rubashkin.

Chassidic Town

Avraham Aharon Rubashkin was born in Nevel—then the Soviet Union and today Russia—on Nov. 30, 1927, the oldest of Getzel and Rosa Rubashkin’s four children. The Rubashkin family, staunch Chabad Chassidim, had lived in Nevel since the times of the Third Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem Mendel, known as the Tzemach Tzedek (1789-1866). Avraham Aharon grew up in the same house as his grandparents, while his father worked long hours in the family wax factory.

Chabad Chassidim had called Nevel home dating back to the era of the movement’s founder, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), and the visage of ah Neveler Yid, a Neveler Jew, gained a distinct place in Chassidic lore.

Chabad’s philosophical teachings plumb the depths of intellectual discovery, and from the movement’s inception there was a special place for the Chassidic maskil, or intellectual (not to be confused with their ideological opposites, the maskilim of the “enlightenment”). On the other hand, one of the foundational innovations of the Chassidic movement was a renewed emphasis on prayer, and thus a second type of Chassid arose, the oved, denoting one who serves G‑d primarily through meditative prayer and the labor of self-refinement.

Neveler Jews were not known for either of these traits. Instead, they became famous and beloved for their lively, uninhibited and joyous approach to Judaism, their simple, gritty faith and their willingness to extend themselves with no limit to help their fellow Jew. Halleluhu b’Nevel (“Praised are those from Nevel”), the Mitteler Rebbe, Rabbi DovBer of Lubavitch (1773-1827), would say—a play on the words Halleluhu b’Navel (“Praise Him with a lyre”) from Psalms and the prayer liturgy. A century later, the Fifth Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom DovBer (1860-1920), would similarly proclaim: “More precious to me is a butcher from Nevel than a maskil [Chassidic intellectual] from Kremenchug!”

Before the Bolshevik October Revolution in 1917, Nevel had been home to some 14 synagogues, but by the time Rubashkin was born, after a decade of ceaseless Communist anti-religious persecution, that number was dwindling.

Still, in 1924, the town became home to the Beit Midrash L’Rabbonim v’Shochetim, or the Rabbinical Academy of Nevel, a branch of Yeshivat Tomchei Temimim Lubavitch established by the Committee of Rabbis in the USSR—an organization founded and chaired by the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—with the express mission of training young men to fill the alarming number of vacancies in the rabbinate and kosher slaughtering. The Nevel academy, led by Rabbi Shmuel Levitin, prepared hundreds of young rabbis and shochetim for this holy work, and was rightly seen as a particular threat by Soviet authorities. To help support the yeshivah, the Rubashkins purchased a second cow for the sole purpose of providing milk for its students..

A year after Avraham Aharon’s birth the Nevel yeshivah was closed down by the Communists and its leaders arrested, news that was trumpeted by Russia’s Yiddish-language Communist press and delivered to the West via the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“The five rabbis who were arrested by the Soviet authorities in Nevel … last month on charges of maintaining a secret Yeshiva, have now been told what their offense was,” reported the JTA on Feb. 1, 1929. The men, Levitin among them, were accused of “ … being counter-revolutionists, plotting against the Soviet government and instigating the population and instructing minors in religion … .”

A year later, Moscow’s Emes,the Yiddish equivalent of Pravda (both Communist Party mouthpieces whose names translate literally as “Truth”), was nevertheless complaining that Nevel was “still the center of illegal Jewish religious activities,” and that the “spirit of the Lubawitscher Rebbe [Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak] still prevails there … .”

Indeed, it did. Not only did the spirit of Chabad Chassidus still permeate the town, it was nearly to the exclusion of anything else. Rubashkin himself would recall how as a child, when he and his friends heard that there was a non-Chassidic Lithunanian Jew at the train station—a misnagid in the old colloquial nomenclature—they all ran there as fast as they could for they had never seen one before.

Rubashkin attended a cheder as a child—he remembered being mocked by non-Jewish and non-religious children as he walked there in the mornings—but by 1938, the darkest days of Stalin’s Great Terror, Rubashkin’s cheder was finally closed by the government. To avoid going to a state school, the 9-year-old was sent to live in Leningrad, today St. Petersburg.

Along with the pressure on Jewish religious life, the Rubashkins and other Chassidic Jews in Nevel faced more basic concerns. In another classic Neveler story Rubashkin liked to repeat, he remembered a time when the town’s citizens received residency permits allowing them to remain there. Although the Rubashkins had lived there for a century, they were denied a permit.

Prior to the Sixth Rebbe’s leaving the Soviet Union in 1927, he had told Chassidim that should they need his advice and find themselves unable to contact him, they should convene a committee of three Chassidim and listen to their conclusion. The Rubashkins came before their special committee, which ruled that the family must make a grand Shabbat farbrengen gathering at their home and invite the entire community.

That Shabbat, the singing, dancing, warm words and l’chaim in the Rubashkin home flowed until long after sundown, continuing on into a Saturday-night melaveh malka. The next morning, Rosa, with her house completely emptied due to the previous day’s festivities, headed to the market to restock her pantry, where she unexpectedly met a distant cousin of her’s, Berta, a member of the Communist Party. Seeing her cousin in an agitated state, Berta asked Rosa what was wrong, and upon hearing the whole story said that, by Divine providence, she sat next to the town’s head of residency permits at Communist Party meetings and would bring it up with him. Berta did just that, successfully convincing the man that the Rubashkins were simple, upstanding workers.

The farbrengen had saved the day.

The War

It was the summer of 1941, and the end was near. Rubashkin would long remember Nevel’s last peacetime Jewish communal event, itself an illustration of Soviet Jewish life. A Nevel rabbi of Polish extraction had some time earlier been arrested by the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police, and subsequently perished in a labor camp. Learning of his tragic end, that summer Nevel’s Jews dispatched a few of their own to the distant camp to dig him up and transport him back home, where he received a proper Jewish burial.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in a three-pronged attack; Hitler’s troops would be in Nevel in no time. On July 7 of that year, Chassidim in town met to discuss what to do. Some chose to stay, others to go, with Getzel Rubashkin firmly in the latter camp. Avraham Aharon would later recall going with his younger brother to place their family Torah scroll for safekeeping in the town’s synagogue, where he met one of his cheder teachers who told the boys their family was overreacting. It was a tragic mistake.

The Nazis entered Nevel on July 15. The teacher, it was later said, was strung up on a street lamp. The remaining Jews of Nevel were placed in a ghetto in August and murdered in September of that year.

The Rubashkins fled Nevel on foot. Avraham Aharon’s grandmother was ill, and they managed to find an old horse with three working legs—and thus not requisitioned for the war effort—to transport her with them. When on Shabbat Rubashkin’s father wanted to stop traveling, his grandfather, Sholom Rubashkin, told his son that he could do as he pleased but due to the direct danger to their lives he was taking his wife and children and continuing; they kept going.

The roads were littered with refugees running from the onslaught, Nazi pilots diving low to rain death down upon the haggard masses, so close, Rubashkin’s sister would remember, that they could see the German pilots’ faces.

In each town they passed through, they paid non-Jewish guides to take them on back roads. In one, having failed to procure a guide, they found themselves in the town center in the midst of a Nazi attack. People scattered to all sides. Suddenly, Avraham Aharon realized that in the panic his grandmother had been left out in the open in the wagon with the three-legged horse. With bullets and bombs flying around him, Avraham Aharon ran towards his grandmother and pulled her to safety. He would come to see that event as nothing less than an encounter with the Divine.

Years later, in New York, Avraham Aharon attended a fundraiser for a prominent Israeli university. A visibly Chassidic Jew at a militantly secular Jewish event, his presence brought him the attention of those around him, with one professor pointedly asking him if he believed in G‑d.

“No, I don’t believe in G‑d,” Rubashkin responded, shocking the crowd. “I saw G‑d.”

First Foray Into Meat

After walking for 11 days, the family boarded a boat that brought them to Chelyabinsk, Russia, where their grandmother passed away. From there, they eventually joined the refugee Chabad community that had formed in Samarkand, Soviet Uzbekistan.

Due first to Soviet persecution and then the outbreak of war, Avraham Aharon never received a proper yeshivah education, and not long after arriving in Samarkand, he began working to help support his family. He would continue going to work every morning for the next 75 years, until his recent illness forced him into the hospital.

In 1945, at age 17, Rubashkin married Rivka Chazanov, also a Nevel native. During the next year, his flax-trading business grew, and he began traveling for work. In one distant city, Fergana, he came upon the sad sight of an old synagogue where after the Torah reading their custom was to not raise the heavy scroll for hagbah but to leave it on the lectern. The reason, the old men explained to him, was that they were all too weak to raise the Torah and due to Communist oppression, no young Jews ever came to synagogue anymore.

A year later, the Rubashkins, like so many of their fellow Lubavitchers, headed to Lvov, the city from which Polish citizens were being repatriated from the Soviet Union. The war-time black market had allowed both father and son Rubashkin to become successful, but when the improvised Lubavitch rabbinical court in Lvov ruled that all Chassidim needed to pool their money so that everyone could obtain forged or false Polish papers to freedom, Avraham Aharon and his father turned over their cash for the greater good.

“All together, it was enough money to save another 200 Jews,” said his grandson Sholom Rubashkin, noting that Avraham Aharon would testify that the sum he personally handed over was 70 times the average yearly salary in the USSR. “My grandfather and his father gave everything they had to the point that afterward they had to stand in the breadline.”

The Rubashkin family successfully crossed into the West, ultimately making their way to Paris, where Avraham Aharon had his first foray into meat. Having received rabbinic training for nikur (removing the nonkosher veins and fats) while still in Russia, he opened a kosher sausage factory. At some point he also oversaw a slaughtering operation in Ireland which supplied European war-refugees with kosher meat.

In 1953, by invitation of his future business partner Alter Lieberman, Rubashkin and his wife, by now with three children in tow, set out for America, the land of opportunity.

A Growing Business

Arriving in New York City, Rubashkin met for the first time the “new” Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—who had just three years earlier assumed leadership of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement and with whom he would immediately form a lifelong bond. While searching for a suitable apartment for his family to live in in the vicinity of the Rebbe’s synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, he wrote a letter to the Rebbe giving a few options, asking which he should choose.

“Where will you be working?” the Rebbe asked him in response during a private audience.

“At the butcher shop in Borough Park,” he answered.

“A butcher works very long hours,” the Rebbe told him. “If you work in Borough Park and live here, you will never be home. It is better for you to live in Borough Park.” Rubashkin lived there until the end of his life.

Together with his partner, they opened Lieberman & Rubashkin Glatt Kosher Butchers on 14th Avenue in Borough Park, but their attempt to break into the notoriously clannish world of kosher butchers nearly failed before it began. Borough Park’s kosher butchers and their meat suppliers did not jump to welcome their new competitors, and jointly decided to lock them out. Rubashkin communicated this to the Rebbe, who in turn contacted the Kopischnitzer Rebbe, Rabbi Avrohom Yehoshua Heschel (1888-1967), a beloved and respected Chassidic rebbe among whose followers were members of the butcher alliance. The Kopischnitzer Rebbe instructed the butchers to remove the upstarts from their blacklist, a kindness Rubashkin never forgot. An oil painting of Rabbi Heschel hangs in Rubashkin’s office to this day.

In the early 1960s, Rubashkin opened Crown’s Deli on nearby 13th Avenue, which initially was meant to be an additional business. The restaurant went through a number of cooks in a short amount of time before Rubashkin’s wife, Rivka, together with Lieberman’s wife, took over in the back of the house, turning the deli into the equivalent of a soup kitchen. Anyone and everyone knew that if they were hungry, they could go to Crown’s and fill up on a hearty meal, paying whatever they could or nothing at all. The restaurant, which closed in the late 2000s, never made a profit.

“Two non-Jewish Italian immigrants once walked in and asked my grandmother who owned the restaurant,” attested Yossi Rubashkin. “She pointed up, to G‑d. They got so excited to encounter such a thing that they hugged each other and said ‘That’s the right answer!’ ”

There were no free rides for Rubashkin, who worked 18-hour days to support his family and build his business. But hard work was in his bones. Over time, Rubashkin’s business grew and he diversified into real estate, textiles and a slew of other enterprises, yet meat and poultry remained at the heart of it. Recognizing that there was a kosher meat supply shortage in the tri-state region, Rubashkin began exploring purchasing a plant close to the cattle sources in the Midwest. With the Rebbe’s blessing, in 1987 Rubashkin purchased a shuttered meat plant in Postville, a tiny economically depressed town in northeastern Iowa. There they could shecht (slaughter), salt and ship meat in numbers previously unseen, soon adding poultry as well.

In a short time, Rubashkin’s son, Heshy, moved to Postville, followed thereafter by another son, Sholom Mordechai, and daughter Chaya Gourarie. Before long, a Jewish community blossomed amid the Iowa corn fields, with the company opening a synagogue, Jewish school and, eventually, a yeshivah.

The Rubashkin’s company, Agriprocessors, revolutionized the way kosher meat and poultry was processed in the United States. It very quickly became clear that from their perch in America’s heartland they could supply the entire country with fresh, kosher meat. They experimented with vacuum-packing technologies and opened distributors throughout the country. While kosher meat had previously been available only to those living near metropolitan areas with large Jewish populations, now it could be easily had in almost any supermarket refrigerator, allowing vastly more Jews of all stripes to keep kosher. Rubashkin saw his work democratizing kosher as his mission and with this in mind intentionally kept his prices low to stay competitive with non-kosher products.

With their trucks laden with kosher meat and poultry coursing through the interstate highway system, Rubashkin and his children regularly had them stop on the side of the road and drop off cases of much-needed meat for Chabad emissaries based in the farthest reaches of North America.

Special Kind of Generosity

Yet his generosity was never limited to meat. Back in the 1970s, Rubashkin was a founding supporter of Yeshivat Bukharim in Kiryat Malachi, Israel; in 1971, he was among those who purchased the Crown Heights building that now houses the Lubavitch Youth Organization, presenting it to the Rebbe as a gift; and in the 1980s he was a member of the board of Lishkas Ezras Achim, a Chabad organization that sent material and spiritual aid to Jews in the Soviet Union.

Rubashkin stubbornly rejected the limelight, and even after he became a major supporter of Colel Chabad, which runs a sprawling social-services network for Israel’s needy, he refused to be honored by the organization. It was only after Colel Chabad’s director, Rabbi Sholom Duchman, wrote to the Rebbe stating he had no honoree and Rubashkin was refusing the recognition, and the Rebbe replied that Rubashkin should accept it, that he acceded. In fact, this being a directive of the Rebbe’s, from that point on he almost never missed Colel Chabad’s annual dinner.

Much more than his institutional support, however, was his ceaseless generosity towards individuals. Anyone who knew him had their own story.

There’s the owner of a bekishe (silk frock) store who not long ago told the family that he lost his biggest customer. Although neither Rubashkin nor his family wore bekishes, an item of dress favored by non-Chabad Chassidim of Polish and Hungarian stock, Rubashkin had an account in the store and would frequently send people to purchase Shabbat and holiday clothing on his bill.

There’s the Brooklyn bank teller who recalled seeing a woman in line in front of Rubashkin have a meltdown when she realized that she’d lost her cash-deposit envelope. Without blinking, Rubashkin took his own, similar-looking envelope and gave it to the woman, telling her he’d just found it on the floor and so it must be hers.

And then there’s the time Rubashkin noticed how a young student at the yeshivah down the block was always at the dorms, even when his peers had gone home for a weekend or a short vacation.

“My grandfather called him over and asked him why,” recalled Yossi Rubashkin. “The boy told him that he can’t afford the few dollars for the bus and anyway, there’s no food at home. My grandfather gave him $60 for a book of bus tickets and filled him up four bags of meat to take home for his family, and told him to come back the next month to take the next four.”

It wasn’t only that Rubashkin gave, it was how he gave. Seeing a volunteer filling a charity order with inexpensive hot dogs, he called him over and, in his trademark Russian-accented bark, exclaimed: “You can eat hot dogs, they eat roast!”

His generosity of spirit did not extend only to his fellow Jews, either. He likewise distributed loans, gifted strollers and sponsored educations for countless non-Jews, both those who worked for him and those who did not. The most important thing for him, said his grandson Sholom, who worked with him closely for more than a decade, was that the person be a hard worker. If they needed a lift, he was there to help.

Never Gave Up Hope

Agriprocessors and its subsidiaries was doing hundreds of millions of dollars in business a year before it all came crashing down. In May of 2008, more than 500 Federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents descended on the Postville plant and arrested hundreds of predominantly Latin American immigrant workers, charging them en masse for lacking proper documentation. In the following months, the prosecution aggressively engaged in what former Attorney General Michael Mukasey later called “prosecutorial abuses,” making it impossible for the Rubashkin family to keep the business afloat. In November of that year, Agriprocessors filed for bankruptcy. Two weeks later, Rubashkin’s son, Sholom Mordechai, the company’s vice president, was arrested and charged with harboring illegal immigrants—a charge that was in fact later dropped.

The government had initially alleged that the Postville plant was home to a range of eye-popping crimes—allegations that promptly appeared in headlines around the country—but none of that ever materialized. Indeed, the State of Iowa at first charged Sholom Mordechai with an overwhelming 9,311 counts of child labor violations. With distinctly less fanfare, the charges were later lowered to 67 counts before an Iowa jury cleared him on everything.

Although it had ostensibly started out as an immigration case, it was in the aftermath of Agriprocessors’ bankruptcy that the government charged him with bank fraud. “And this is where things went terribly wrong,” wrote former Clinton deputy attorney general Philip B. Heymann in The Washington Post in 2016. “The sentence for bank fraud depends on the amount of the loss to creditors. In this case, the prosecution deliberately increased the amount of the loss—and thus the length of Rubashkin’s sentence.”

While the company’s assets had been valued at least at $68 million, evidence shielded from Rubashkin’s attorneys pointed towards the prosecution interfering in sale proceedings and threatening the prospective buyers that the government could seize everything if any member of the Rubashkin family stayed involved in the company after the bankruptcy sale. The government’s unlawful “No Rubashkin” clause led to “Agriprocessors [being] sold for $8.5 million, resulting in a huge loss to creditors and what is essentially a life sentence for … Rubashkin.”

In 2010, Rubashkin was found guilty, and the judge, who it was later discovered had engaged in secret ex parte communications with prosecutors, condemned him to 27 years in federal prison—two more years than the prosecutors had asked for. Aside from the breaches that led to Rubashkin’s prosecution, the sentence itself was wildly out of proportion, “scandalously harsh” in Mukasey’s words.

So egregious was the prosecutorial misconduct in this particular case—documents later recovered by the defense revealed that the prosecutors had, among other steps, knowingly put forward false testimony—that 107 former Justice Department officials, including five former attorneys general, six former deputy attorneys general, two former directors of the FBI, 30 former federal judges and other leading jurists, requested that the Justice Department fully review its handling of the case and sought other avenues of redress. The U.S. Attorney in Iowa even claimed it was the family’s financial resources behind such broad support, but Heymann underlined that all of the officials were working on it pro bono, and “among other things, former deputy attorneys general Larry Thompson, Charles Renfrew and I have traveled to distant meetings and volunteered considerable time to this matter, all on our own nickel.”

Finally, in December of 2017, President Donald Trump, with the backing of everyone from Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) to then House Minority Leader, now Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), commuted Sholom Mordechai’s sentence, allowing him to finally return home to his wife and family.

The joy felt on that day by countless individuals who had worked to assist Sholom Mordechai Rubashkin, as well as many in the Jewish community who saw the prosecution’s conduct of doling out a separate standard of justice as being anti-Semitic, could not outweigh his father’s. It was to Avraham Aharon’s Borough Park home that his son first went after his release.

Nevertheless, “my grandfather never stopped believing in America’s promise,’ ” recalled his grandson Sholom. “He was very grateful for the life he got here, and told me more than once, ‘America is a good land.’ ”

Throughout that ordeal and the many others he faced during his long life, Rubashkin never lost belief in G‑d nor the conviction that it was all in the hands of the Almighty.

“He had unwavering faith in G‑d and always accepted everything that came his way,” said Sholom. “He never had any complaints to G‑d, only thanks and belief it was for the good.”

Rubashkin knew firsthand that even the darkest situation could turn around in the blink of an eye. Typical of him, he had a story to illustrate that.

Back in Samarkand during World War II, news from the front came sparingly. He knew there was a war going on, and by that point, everyone knew to some extent of the Nazi’s murderous decimation of their hometowns and families. Yet each day he got up and did what he had to do. One morning, Rubashkin awoke to the radio blaring that the Nazis had surrendered. People began dancing in the streets outside.

“My children,” he would knowingly say, “one day you’ll wake up and the war will be over.”

Rubashkin is survived by his wife, Rivka, and children Gutol Goldman (Miami Beach, Fla.); Sara Balkany (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rochel Leah Rosenfeld (Safed, Israel); Yossi Rubashkin (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Moshe Rubashkin (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Sholom Mordechai Rubashkin (Monsey, N.Y.); Chayala Gourarie (Postville, Iowa); Heshy Rubashkin (Postville, Iowa); and Chana Zelda Minkowicz (Brooklyn, N.Y.); in addition to many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

He is also survived by his siblings, Rochel Duchman, Gavriel Rubashkin and Dania Raskin, all of Brooklyn, N.Y.

Join the Discussion