The story of Rebbetzin Rachel Altein’s life is intertwined with the history of Chabad in America like that of few others. She served for decades as the English language editor of Di Yiddishe Heim, a periodical by and for Jewish women that featured a vibrant mix of creative writing, opinion pieces and historical vignettes, alongside articles delving into Jewish law and Chassidic teachings. From her teenage years on, she was a teacher and educator, and served alongside her husband at the helm of schools in Pittsburgh, Pa.; New Haven, Conn.; and the Bronx. N.Y.

For the countless individuals to whom she was a mentor and guide, her open home doubled as a hands-on introduction to authentic Jewish living. Boundlessly energetic, she was at once unwaveringly principled and supremely practical. She will especially be remembered by the generations of women who studied with her as new brides. She was a master teacher, warmly and wisely imparting the laws and customs by which to sanctify their marriages and their homes.

She passed away on April 13 at the age of 95 after complications due to the coronavirus.

Born in 1924, young Rachel Devasha was 18 months old when she arrived at Ellis Island from Soviet Russia, together with her parents, Rabbi Yisroel and Rebbetzin Sheina Jacobson. They came with the express blessing of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—with the mission to expand the Chabad community and pioneer Chabad activism in the United States. Her father was soon appointed chairman of Chabad’s oldest organization in the United States, Agudas Chasidei Chabad of America, and became a renowned activist and teacher in his own right.

At that time, Jewish schools for girls had not yet been established in the United States, so young Rachel attended public schools, as did all her Jewish peers. She was a good student who graduated with honors and was offered scholarships to attend prestigious colleges. At the same time, she proudly upheld the deep-rooted Jewish values and Chassidic spirit that her parents had brought with them from “the Old World.” She did not eat in the school cafeteria, but brought kosher food from home. At a time when many Jews were keen to be absorbed into American society and to absorb American culture, it was clear to her peers and teachers that Rachel was different. She was a young woman of conviction, unswayed by what others did or thought she ought to do.

According to her oldest granddaughter, Mrs. Sara Morozow, Rachel’s years in public school were formative; she emerged independent-minded, principled and persuasive. She was unapologetic about her beliefs and uncompromising in her determination to live by her principles and share them with others.

Rachel’s childhood home in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., was the center of Chabad Chassidic life, constantly abuzz with visitors, meetings, Torah classes and festive gatherings (farbrengens). As a teenager in the early 1940s, she herself would become an activist, leading the girls division of the “Mesibos Shabbos” youth group, whose chapters met on Shabbat afternoons to hear inspiring stories and to celebrate the living heritage of Torah learning and mitzvah observance.

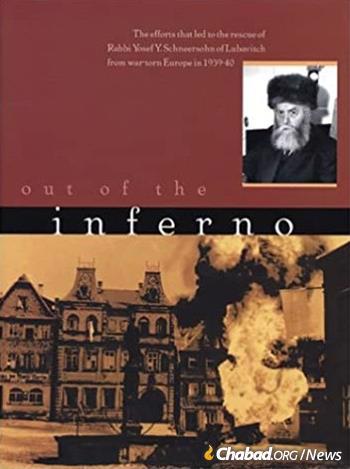

Her teenage years also saw the outbreak of World War II. Although geographicaly removed from the horrors of the Holocaust, these events were deeply felt by her personally and by the American Jewish community as a whole. With Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak trapped in Nazi-occupied Warsaw, her father led a dramatic campaign to extricate him and bring him to the safety of New York. Many years later, Rebbetzin Altein, together with her grandson Rabbi Eliezer Zaklikovsky, co-authored a detailed archival chronicle of these events in Out of the Inferno: The Efforts That Led to the Rescue of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn of Lubavitch from War Torn Europe in 1939-40 (Kehot Publication Society, "Kehot Publication Society, 2002) with assistant editor Rabbi Eliezer Zaklikovsky.

In that work, many individuals who were not saved were also memorialized. The files in her father’s archive, Rebbetzin Altein wrote, “bear witness to the painful, heartbreaking and ultimately futile history of the efforts to bring to America those chassidim who were still in Warsaw and Riga … May the Almighty avenge their blood; may we forever cherish their blessed memory.”

Her concluding words carry an autobiographical undertone that is as subtle as it is poignant: “Let us praise the One Above for saving the Rebbe and all those who did survive—so many of whom were His chosen instruments to revive and strengthen Torah life in America and in the whole world.”

As was the case with so many of the projects that she spearheaded, she had first consulted with the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—asking if he would approve the initiative to publish the relevant documents from her father’s archive. The Rebbe’s written response affirms his “approval, and more than that, great applause, especially since many, many readers will surely be able to learn much from it, particularly concerning vital, authentic activism and Chabad [activism] in particular.”

Indeed, much can be learned about such activism from the life story of the woman to whom these words were addressed.

‘A Rare Professional in the Realm of Education’

In the spring of 1943, while Rachel was teaching at the Beth Rivkah and Beth Sarah schools for girls in New York, a match was suggested for her with a young rabbi by the name of Mordechai Dov Altein. Mordechai had been a student of her father, and back in 1939, he was one of a small group of American yeshivah students who traveled to Otwock, Poland, to study in close proximity to Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak. With the outbreak of the war, they immediately returned to the United States, and by 1943, Mordechai was in Pittsburgh, where he had been dispatched to open an affiliate school of the central Tomchei Temimim Yeshivah in New York. (The school, Achei Temimim-Yeshiva Schools of Pittsburgh, continues to flourish to this day.) When informed of the proposed match, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak expressed his approval, but due to their respective teaching obligations advised them to begin their courtship by mail.

The engagement celebration was held on the 18th of Elul 1943, with the participation of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson—who would later succeed his father-in-law as Rebbe—together with his wife, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka. The following day, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak penned a letter exhorting and blessing them to “work as one in the tent of Torah and fear of heaven, and you shall be successful in your holy work, and it shall be good for you, physically and spiritually.”

For his part, Rabbi Mordechai Altein would become a scholar of repute and one of Chabad’s leading rabbinic authorities. Rebbetzin Rachel Altein would likewise make her mark as a pioneering leader of Jewish women’s education, activism and literature.

The wedding was held a few months later at the Empire Manor hall in Brooklyn with three illustrious rabbis officiating: the aforementioned Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gurary and Rabbi Chaim Moshe Yehoshua Twersky-Schneersohn, the Rebbe of Tomashpol (1867-1959).

Rabbi Menachem Schneerson also delivered a speech in honor of the occasion, in which he spoke of the marriage of two educators as a celebration of hope that unites and uplifts the entire Jewish people even as a large portion of the Jewish people undergo terrible suffering. Delivered as the Holocaust was still underway in Europe, this speech has the ring of an agenda-setting manifesto, and suggests that in the marriage of Mordechai and Rachel Altein he saw the promise of light at the end of a dark tunnel:

Drawing a parallel to the festival of Chanukah, which would begin just a few days later, the future Rebbe reminded the crowd that though the Jewish people were weak and few, they nevertheless stood strong and ultimately prevailed. While their Greek oppressors have long been reduced to mere history, the Jewish people and their Torah continue to be miraculously preserved. Just as the one jug of pure oil was sealed with the signet of the High Priest, so the purity of our children must be assiduously guarded with the signet of a Torah education. Against those who despair, claiming that the oil cannot burn for more than a single day, we are assured that the oil will burn and shine forth with ever increasing brightness and without any pause. Even in America, young Jews can unabashedly and openly profess their faith in the One G‑d. Even at a time of immense tragedy, Jews can and must rejoice in the knowledge that the Torah has the power to illuminate not only the home of the newlywed couple, but ultimately the entire world.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak communicated the hope he invested in them, along with congratulations and blessing, in the form of a letter: “You shall build a Jewish home on the foundations of the Torah and the mitzvot, and you shall be happy, physically and spiritually … [and through your educational work] you shall raise students who have fear of G‑d and are knowledgeable in Torah … ”

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s regard for the young bride is expressed in a letter penned shortly after she had moved to Pittsburgh, where she began working alongside her husband. The Rebbe exhorted the addressee, a resident of that city, to “aid Rebbetzin Altein, who is, with G‑d’s help, a very capable pedagogue and a rare professional in the realm of education.”

Over the course of the next 18 months, the Alteins would also be instrumental in setting up Yeshivas in Bridgeport and New Haven. In 1944, prior to Rosh Hashanah, they moved to the Bronx, to take up the pulpit of the Nusach Ari Synagogue. Within short order, they had established a yeshivah there as well (a girls’ school was later established as well), and within a few months, Rachel gave birth to her first child. They would make the Bronx their home for more than 40 years.

‘A Chassidic Mind and Spirit’

In 1946, the young rebbetzin began writing for a children’s magazine published by Chabad’s National Committee for the Furtherance of Jewish Education (NCFJE), which was distributed to participants in the “Released Time” Jewish education program for public school students. At the same time, she also explored the possibility of taking up an active teaching position. Given the distance between the Bronx and suitable schools for girls in Brooklyn, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak advised her to reconsider, writing that “in my opinion, the work of writing edifying reading material is of greater benefit in the field of education.”

At the time, the Bronx was a relatively comfortable, middle-class area. But life was not easy for the Alteins. They were waging an uphill battle to raise the spiritual standards of Jewish life and education, and were constantly faced with the financial pressures that come with devoting one’s life to communal work. But their resolve was strengthened by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s reassuring advice, blessing and encouragement. The constant flow of correspondence between the Altein family and the Rebbe’s secretariat, both regarding personal life and their work as educators, testifies to a very special bond. Indeed, when the Alteins’ second child was born, Rabbi Menachem Schneerson suggested that they seek permission from Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak to name him for the latter’s father-in-law, Rabbi Avraham Schneersohn of Kishinev, who had passed away in 1937. Permission was granted, and Rabbi Menachem Schneerson attended the brit.

In his final letter to the family—signed just three days before he would pass away, on the 10th of Shevat 1950—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak extends his blessing that “G‑d should strengthen the health of all of you, and arrange for you a dwelling that befits you, and provide you with good livelihood.”

A little less than a year later, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson—who had now succeeded his father-in-law as Rebbe—wrote to congratulate them on putting down a deposit on a new home and encouraged them to have no second thoughts despite the increase in financial cost that it entailed. He concluded with a few lines expressing his confidence that Rebbetzin Altein possessed all the resources necessary to overcome any feelings of despondency: “She herself is master of a Chassidic mind and spirit. ... She shall truly rejoice over the good that G‑d has bequeathed her until now, and joy breaks the constraints to fully provide even that which has until now been lacking.”

Rebbetzin Altein took the Rebbe’s words to heart, and in the next few years intensified her activism among the young Jewish women in her neighborhood, who often regarded their heritage more as a burden than as a gift. Building protective walls, she understood, would further reinforce the impression that Jewish life and modernity were at odds. Instead, she set out to engage and persuade, organizing classes and opening her home to all who wanted to learn and experience the authenticity and richness of the Torah way of life.

In 1952, the Rebbe had called for the creation of N’shei Chabad, the Chabad Women’s Organization, to be led by women and for women, and Rebbetzin Altein would quickly emerge as one of its most prominent activists. While today it is commonplace for Chabad rebbetzins to teach Torah classes to other women, back in the 1950s this was all but unheard of. Rebbetzin Altein was one of the very first to take up the banner of Jewish women’s Torah learning, and she was directly empowered and encouraged to do so by the Rebbe himself.

In a letter penned in 1954, the Rebbe encouraged her to expand her activities even further, “she shall be active in her sphere of influence not only to increase Jewish life in the ordinary sense, but also to disseminate chassidic teachings.” He advised her that “though baking bread is necessary for the sustenance of humanity, nevertheless, one who has been trained in the craft of drilling pearls should not busy themselves with lesser work that can be done by others.”

This was advice that Rebbetzin Altein would pass on to many who sought her counsel in years to come. A woman must delegate lesser work and always prioritize her special talents. Family members relate that this was further reinforced when the Rebbe sent her a check with the specific intention that it be used to help cover the expense of household help.

Responding to a report that she submitted towards the end of 1955, the Rebbe wrote: “I am glad to note that you are now using your ability and qualifications with which you have been endowed, to exercise a good influence in your environment, especially among the women. I trust that you are also making an effort to spread the teachings of Chassidus in particular.”

In this letter and subsequent letters, dating from 1956, the Rebbe also addressed her concern that many women of her acquaintance would not yet be receptive to Chabad ideas. These letters, which are filled with advice of immense practicality to anyone who strives to realize their potential to the full, can be read here.

Beginning in 1953, Rebbetzin Altein spent several summers at Camp Emunah, a camp for girls in upstate New York, where she helped run the educational program. In 1957, she accepted the position of camp mother at Camp Gan Israel for boys, also in upstate New York. For her, these summers provided a welcome respite, a wholly Chassidic environment in which she and her children did not need to constantly swim against the current and could draw renewed strength to return to their work in the Bronx. These steps too were taken in consultation with the Rebbe, who expressed his approval but also cautioned her to ensure she continued to take care of her community even while away.

Her son, Rabbi Avrahom Altein—himself a vetern Chabad emissary to Winnipeg, Canada, and an indispensable consultant to Chabad.org’s editorial team—recalls that during this period the Bronx was a spiritual desert: “Most of the children who enrolled in the school established by my parents did not grow up in homes where Shabbat was observed. It was not a very hospitable environment for the values that she stood for. Yet she was unbending. My mother was truly, truly dedicated to educating us, to training us into Chassidic life in all its rigor. She constantly set the highest standards, and reminded us of what our aspirations should be. The Rebbe’s words are a very fitting characterization, she possessed a Chassidic mind and Chassidic spirit.”

“From the age of ten and onward,” Rabbi Altein told Chabad.org, “I was rarely at home. My mother wanted us to be immersed in the atmosphere of Torah and Chassidus, and I went to study at the United Lubavitcher Yeshiva on Bedford Avenue and Dean Street in Brooklyn (known as “Bedford and Dean”). In Brooklyn, my grandparents took care of me. When my grandfather [Rabbi Jacobson] went to teach Chassidus at the Central Chabad Yeshivah in 770, I would accompany him and study Tanya with some of the senior students.”

Editor of ‘Di Yiddishe Heim’

Beginning in 1958 Chabad Women’s Organization began publishing a periodical magazine titled Di Yiddishe Heim (“The Jewish Home”), and Rebbetzin Rachel Altein was appointed its English language editor. She would serve in that role for more than three decades, soliciting articles, working closely with writers to shape their content, and submitting final drafts to the Rebbe himself for final editing.

The Rebbe did not simply offer encouragement from the sidelines, but was personally invested in Di Yiddishe Heim’s publication, and saw it as a significant vehicle for the development and communication of a Chassidic vision of Jewish womanhood. He diligently marked up each draft line by line, making interventions on content, phraseology and spelling.

For her part, the magazine’s editor quickly emerged as an eloquent and witty exponent of what it means to be a modern “woman of valor” (aishet chayil). On the first page of the first issue, she wrote:

“The basic role of the Jewish woman, “bat melech” [the king’s daughter] in her devotion to her household, and her creativity in this inner sanctuary, has been to nurture with care the flower of Jewish Youth. But at times of dire need and stress, the “aishes chayil” has gone out of her four walls, to give of herself, for the strengthening of the Jewish community.”

With these words, Rebbetzin Altein heralded the new era of Jewish women’s activism. This activism was not intended to displace tradition, but rather to defend, reinforce and glorify a vision of Jewish womanhood that raised the eternal values of the Torah over and above any other priority.

Rebbetzin Altein wielded her editor’s pen with judicious decisiveness. She published a colorful array of voices, perspectives and debates, yet maintained a keen sense of when to meet point with counterpoint. Bonnie J. Morris—a self-described feminist historian who wrote an important study titled Lubavitcher Women in America: Identity and Activism in the Postwar Era (State University of New York Press, 1993)—devoted an entire chapter to Di Yiddishe Heim and wrote that in its pages women emerge as “producers and agents of Hasidic ideology ... Poetry, satire, editorial, scholarly essay; all literary forms were suitable for conveying the spiritual message to readers.”

Morris also reports the characteristic self-effacement with which Rebbetzin Altein reflected on her work:

“Di Yiddishe Heim is just one aspect of what Lubavitch is all about—spreading the teachings of Torah and mitzvos in every way we can find. It is not published in the name of literature Jewish or otherwise, general culture, or women's culture per se.”

For all her gifts as educator, writer and editor, she never lost sight of the bigger picture. She identified first and foremost as a Lubavitcher Chassid, and it was from that axiomatic starting point that everything else extended.

The Rebbe’s championship of Rebbetzin Altein’s editorial work was underscored in 1965 when he published a new edition of Likutei Torah, a classic compendium of Chassidic discourses by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi. Rebbetzin Altein was among a select group of individuals—all energetic disseminators of Chassidic teachings—who the Rebbe personally selected to donate the necessary funds. Each of them was presented with a copy inscribed in his own hand with the following message:

“With blessing for the arousal of the hearts to serve G‑d in all aspects, and especially in the dissemination of the wellsprings [i.e. chassidic teachings], and by way of light and joy, spiritually and physically.”

Family members recall that when Rabbi Altein offered to take the volume home on his wife’s behalf, the Rebbe’s secretary informed him that it would remain in his custody until she was able to receive it in person.

On another occasion, the Rebbe similarly underscored her autonomy by noting that the Megillah is named only for the female heroine, Esther, and not “the Megillah of Esther and Mordechai.” “In a humorous vein,” he continued, the same could be said of her: “Di Yiddishe Heim is not under the name of Mordechai, may he live [referring to her husband, Rabbi Mordechai Altein],” but rightly bears her name alone as editor.

The ultimate signal of the Rebbe’s regard for her ability and judgment came in the summer of 1991. By this time, the number of people seeking the Rebbe’s counsel and blessing had been increasing exponentially for years, and the Rebbe transferred complete editorial responsibility to Rebbetzin Altein with the following note: “Time does not at all allow for me to edit and I will rely on her edits, may G‑d give success.”

A Public Speaker and a Personal Mentor

At some point in the 1960s, the Rebbe asked Rebbetzin Altein to start teaching the laws and customs of family purity to new brides in the Chabad community and also to students at Yeshiva University High School for Girls—Central Manhattan. From that point on, she would regularly make the trip from the Bronx to Manhattan and Crown Heights, and would become a mentor to hundreds of young women over the course of many years.

When asked why the Rebbe singled her out for this role, family members responded that she was unique in her ability to engagingly and clearly communicate an authentically Chassidic perspective on the sacred nature of marriage and the spiritual significance of gender. In addition, she wasn’t afraid to introduce sensitive topics to young audiences. Both of these qualities were especially crucial at a time when many young people were quick to dismiss any and all conventions as obsolete.

In the few days since her passing, community forums have filled up with women sharing their memories, going back as far as 1970. She is described as “a dynamic teacher” with “such a happy disposition.” Her presentations were “laced with humor” and “common sense.” At the same time, she was “a real no-nonsense person” and would stand for “no compromises or concessions towards a more popular, secular lifestyle.”

For many of her students, especially for those who did not grow up with a strong Jewish education and only awoke to the beauty of Torah later in life, these classes were the beginning of relationships spanning decades. “All through the years,” wrote one woman, “from before I became a Chassid … right up to my own children getting married and establishing families of their own, she held my hand.”

Another student remembers accompanying her to address a large and diverse public audience; listeners of religious and secular orientations alike proved receptive to her message, because her delivery was “dynamic,” “clear” and “to the point.”

Her son, Rabbi Avraham Altein, likewise notes that although the Rebbe generally advised against staged debates with other ideologues. On one occasion he nevertheless authorized Rebbetzin Altein to participate in a debate on the role of women in Judaism. “It was a hostile audience. But when they tallied the votes, it came out as a tie.”

‘Pillar of the Home’

As recalled by Mrs. Sara Morozow, her grandmother would often say that “true liberation comes from family.” Prior to all her roles as a teacher, editor and public speaker, Rebbetzin Altein was a mother and a homemaker, devoted to her children and to her husband.

Her grandparents’ house in the Bronx, says Mrs. Morozow, was always astir with people: “The phone was always ringing. She was always extremely busy, organizing, teaching, and helping. And she was able to pull it all off because she was practical and organized. And that’s one of the things that she taught people: how to run a kosher home, how to shop and prepare for Pesach, how to keep things in order. She was never afraid to give people the advice they needed to hear. And she and her husband were just a great team, they ran the home together, they helped and taught people together. They were in harmony with each other in a really beautiful way.”

Even as the Bronx entered a period of decline, and the vast majority of the local Jews moved to other neighborhoods, they continued to follow the Rebbe’s directive that they should remain at their post, and maintain a center of Jewish activity there. They did not leave until a new couple moved into the area and opened a Chabad House.

Rebbetzin Rachel Altein was predeceased by her son Yossi (Yosef Yitzchak, b. 1959), to whom she dedicated her book Out of the Inferno, in 2000, and by her husband Rabbi Mordechai Dov Altein, just a few months ago.

She is survived by their children, Chana Gurary (Montreal, Canada); Rabbi Avrohom Altein (Winnipeg, Canada); Rabbi Leibel Altein (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Malka Cohen (Manchester, England); Sara Pinson (Nice, France); and Sima Zalmanov (Safed, Israel); in addition to many grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren.

Join the Discussion