Miriam Popack, an educator, a warm advocate for Torah Judaism and a force behind the annual midwinter convention of the Lubavitch Women’s Organization (N’shei uBnos Chabad) since the gathering’s inception in 1962, passed away on Jan. 31. She was 95 years old.

She was born Miriam Altein, the fourth child of immigrants in New York, in an era when staunch adherence to Judaism was seen as something belonging to grandparents and greenhorns. Yet she remained steadfast in her dedication to mitzvah observance, a trait ingrained in her by her parents’ inspiring examples.

Her mother, Chana, was a scion of a prestigious rabbinic family. Although Chana Spalter never had any formal Jewish education, she would listen carefully to the steady stream of people who would consult with her father, a dayan (rabbinic judge) back in Poland.

Following a wave of pogroms that swept through Eastern Europe in the first years of the 20th century, at the age of 18, Chana decided she must immigrate to the United States. After working for a year as a seamstress, she finally saved enough for passage to New York in 1910. Despite many challenges, she maintained her resolve to observe Shabbat and other mitzvahs, just like in Poland. In New York, she met and married a like-minded immigrant named Tzvi Hirsch Altein. No matter how difficult, they were determined to raise a family for whom Torah and mitzvah observance would be of primary importance.

The Alteins’ two sons, Mordechai and Yisrael, were given a yeshivah education, but there was nothing like that for girls in 1930s. So Miriam went to public school in the Brooklyn neighborhood of East New York, where the family lived. Her Jewish education was provided mostly by her parents.

“Her friends would go to the beach on Shabbos,” says her daughter, Rivie Feldman, “but she joyously celebrated with her family at home.”

Devotion to Torah

In 1938, while Miriam was in high school, Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan opened the first Bais Yaakov school for girls in New York, and Miriam joined what was then a two-hour after-school program. After graduating high school, she attended Kaplan’s Bais Yaakov teacher’s seminary.

In the late 1930s, her brother, Rabbi Mordechai Altein (who recently passed away at the age of 100), became a student of the noted Chabad-Lubavitch Chassid and activist Rabbi Yisroel Jacobson, a source of deep scholarship and inspiration. Along with her brothers, she was attracted to the Chabad approach. This intensified in 1940, when the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—arrived in the United States.

On Shabbat afternoons, she would gather Jewish children and teach them the basics of Judaism over kosher treats. In a Jewish world with precious little meaningful programming for young people, the Mesibos Shabbos gatherings for Jewish children in cities like New York, Pittsburgh and Chicago were among the very first Chabad activities in America.

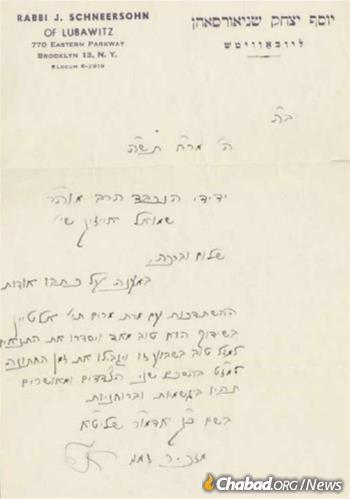

In 1945, she was introduced to Shmuel Isaac Popack, a Chabad yeshivah student her brothers knew and thought of in high esteem. Throughout their courtship and engagement, and all the way through their wedding, the Sixth Rebbe took a keen interest in their progress, providing a steady stream of blessings and advice.

Although not well-off at the time, the Popacks established an open home where anyone was welcome. While Shmuel Isaac set off supporting his family, Miriam remained home to care for their growing brood, whom she carefully raised in the Chassidic spirit she had observed at home and learned from the Rebbe, whom she had come to view as a beloved father figure.

Taking a Lead Role

In 1950, the Sixth Rebbe passed away. Living in a walk-up apartment and tending to a toddler with a high fever, she watched brokenheartedly the thousands who came from all over to attend the funeral. It was a Sunday morning she said she would always remember.

However, despite the pain, she and her husband were comforted in the knowledge that the Sixth Rebbe was succeeded by the the Seventh Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—whom they had come to know and admire.

In 1952, the Rebbe called for the establishment of N’shei uBnos Chabad, the Lubavitch Women’s Organization, and Miriam Popack became one of its first members and leaders, eventually serving as president.

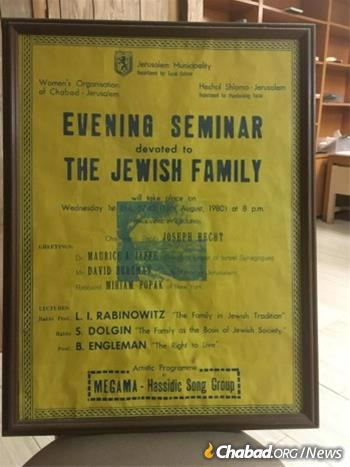

The organization was and remains unique. It was the first major Jewish women’s organization that did not emphasize the objectives of fundraising and auxiliary activities, but education: education of the self and of others. They held a number of events throughout the year, including conventions in Brooklyn, during which the Rebbe would address the attendees. In the early 1960s, Leah Kahan suggested that the women hold an additional annual convention in another city every year.

Starting with the inaugural convention in Boston in 1962, Miriam Popack led the first of what would be 56 gatherings to date, held all across North America, from Montreal to Miami and from Los Angeles to Burlington, Vt.

The Rebbe was interested and involved in many aspects of the conventions. Despite his heavy workload, he made the time to help them plan every detail, often providing guidance and input that ranged from the design of promotional material to helping them select the themes and vet speakers. Miriam Popack would often call the Rebbe’s office as soon as Shabbat ended to deliver a preliminary report before writing up a fuller report in the days following.

The Rebbe guided the women to see the convention as more than just an opportunity for them to celebrate, study and inspire themselves; rather, they were to be a source of inspiration for the host city. In an undated memo from his secretariat, the Rebbe issued two guidelines regarding where the conventions were to be held: a. The city needs to have a Jewish population; and b. There needed to be women on the ground who could shoulder some responsibility for planning and executing the event, which invariably extended over a weekend.

The conventions thus brought together a diverse group of women, who would be encouraged and learn from each other. The Rebbe would regularly send dollar bills to be distributed to each of the attendees, as well as write a letter of blessing to be read at the convention.

One year, the convention was held in Worcester, Mass., and the mayor gifted the Rebbe with a ceremonial key to the city. Upon returning to Brooklyn, Miriam Popack sent her husband to bring the key to the Rebbe’s office. Shortly thereafter, she was invited to deliver the key directly to the Rebbe in person.

A memorable convention was in suburban Detroit in 1979. That weekend, heavy snowfall blanketed the Northeast, which prevented many women from returning home. Distressed, they called the Rebbe’s office from the airport, requesting his blessing and guidance.

The Rebbe’s reply reframed the situation from a setback to an opportunity. Rather than a source of distress, the Rebbe explained, the extra day in Detroit was G‑d’s way of telling them that they still had unfinished business to accomplish there.

The women immediately fanned out across the area. Some went to Ann Arbor to meet with local Jewish college students. Others went to shopping centers and malls, where they distributed Shabbat candles. And yet others remained in the airport, where they were interviewed by local television stations, which covered the unusual turn of events.

A Long and Varied Career

After chairing her 25th convention, Popack wrote to the Rebbe that she was ready to pass on the duty to another. Characteristically, the Rebbe guided her to remain at the helm, but to enlist the help of others to assist her. From then on, she was joined by Feldman and Faige Rosenblum.

Another memorable convention was in the winter of 1991 in Minnesota, which coincided with the beginning of Iraqi shelling of Israel during the First Gulf War. The program included Israeli singer Ruthi Navon. Worried about her family in Israel, Navon wanted to cancel her appearance; however, the Rebbe encouraged her to carry on, explaining that faith and joy would contribute towards Israel’s safety.

To further encourage the women, on the Friday morning of the convention, the Rebbe urged women who had not been planning to attend to go and show their support. The Rebbe requested that a list of those attending as a result of his call be submitted to his office.

In addition to her duties at N’shei Chabad, Popack held another communal duty. At the behest of the Rebbe’s chief of staff, Rabbi Mordechai I. Hodakov, she kept a Crown Heights community calendar so that communal events and family celebrations not accidentally be scheduled on the same evening. This took up a great deal of time, especially, it seemed, when she was about to sit down with her family for dinner, but Popack graciously took calls throughout the evening from brides and grooms eager to secure dates for their weddings.

She was instrumental in ushering in the new wave of beautiful mikvahs that have been built all around the world.

In 1971, she reported to the Rebbe that the community of Long Beach, Calif., was in need of a mikvah. The Rebbe responded by sending $1,000 towards the construction of a new facility. The result was a luxurious mikvah, which challenged the misconception that they were all decrepit, dirty and old-fashioned.

This Long Beach mikvah is widely regarded as a catalyst that inspired thousands of beautiful mikvahs now gracing Jewish communities large and small.

A Source of Kindness

Welcoming guests was a major part of the Popack home. In the 1960s, when long-haired hippies began pouring into Crown Heights to enjoy Shabbat in the Rebbe’s presence, the Popacks invariably hosted as many as they could fit, valuing each guest as an individual deserving of royal treatment.

Feldman remembers one year when her father did not come home from services on the first night of Passover. Worried, the family waited around the set Seder table. He finally appeared, accompanied by a stranger, and explained his absence. He could not come home to his wife on Passover eve without a guest, and the only way he could find a person in need of a meal was to wait for everyone to leave the synagogue and see who remained. His guest had recently immigrated from the Soviet Union and was planning to have a quiet Seder in his rented quarters—until he was cajoled into joining the Popacks, who would become lifelong friends with him and his family.

Miriam Popack taught for decades at the Talmud Torah (after-school Judaic program) at the New Hyde Park Jewish Center, where she developed a warm bond with her students and their families. At the age of 59, she embarked on another career: school counselor at the Yeshivah of Crown Heights in the Mill Basin neighborhood. She remained on the job until she was 80 years old.

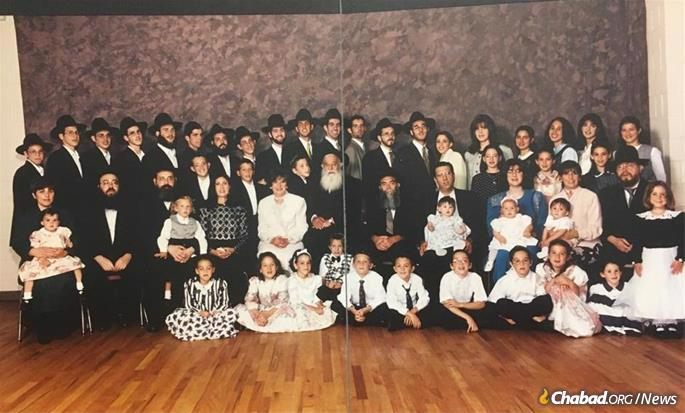

Shmuel Isaac and Miriam Popack watched with pride as their children took up posts as Chabad emissaries across the United States and Israel.

Predeceased by her husband in 2012, she is survived by their children: Chana Piekarski (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Yisroel Meir Popack (Denver); Joseph Popack (Long Island, N.Y.); Toby Hendel (Migdal HaEmek, Israel); Rivie Feldman (Brooklyn, N.Y.); and Zeesy Raskin (Vermont); in addition to dozens of grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Join the Discussion