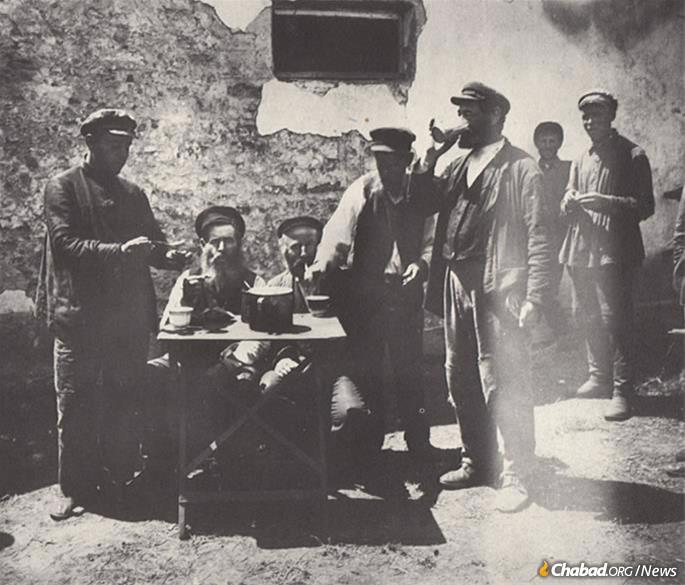

It was the end of 1928, and food shortages were once again starting to hit the Soviet Union. By November, “Leningrad had already introduced food rationing … Moscow soon followed, as did other industrial cities, going beyond bread to sugar and tea, then meat, dairy, and potatoes.”1 The situation in Ukraine and Belarus, in whose towns and villages the vast majority of the country’s 2.7 million Jews lived, was even worse.2 And it was only the beginning.

“At every time the Jewish people have had their poor, even the destitute, those lacking bread and wearing tattered clothing,” wrote the sixth Chabad-Lubavitch Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, in an early 1929 letter outlining conditions in the USSR. “But impoverished people such as our eyes have seen during these years of famine and since the end of private enterprise, my lips do not err if I say that in all countries there are none like them, and a scene such as this has never been witnessed by a foreigner.”3

“People have lost the feeling of being ashamed of acting as paupers … ,” one anonymous eyewitness wrote in a letter titled “The New Book of Lamentations,” published on the pages of New York’s Hadoar in mid-1928. “In the villages, on the cross-ways, we met groups of Jewish children stretching out their hands to every passer-by. Woe to the eyes that see this! One who has not seen the little, thin, consumptive hands grabbing the piece of bread from the peasants or farmers can have no conception of the meaning of … hunger.”4

Although exiled from his home and flock in Russia since his 1927 arrest and release by the Communist government, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak was closely attuned to the Jewish condition in the Soviet Union, managing a vast network of underground religious and humanitarian activities from his temporary base in Riga, Latvia.5

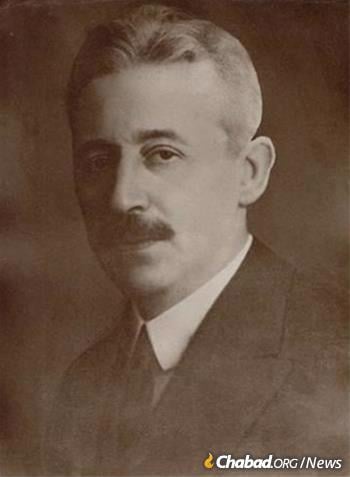

“It is necessary for the work in Russia to be continued illegally and secretly,” wrote Dr. Bernard Kahn, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) representative in Berlin in a confidential February 1928 memo to the JDC’s Dr. Cyrus Adler in New York. “It seems that Rabbi [Schneersohn] is the only one who knows really reliable and [skillful] people, in Riga as well as in Russia, whom he needs for this kind of work. Then too, he is the only one who gets all the information from Russia through a net of people, and he is in a position, although he is staying in Latvia, to obtain new people in Russia to replace others who can no longer be useful to the work for various reasons.”6

Now, pained by the terrible material conditions of his Russian Jewish brethren and months before Passover of 1929, the Rebbe foresaw yet another looming crisis.

“According to reports that have come from the entire breadth of the Soviet Union … central Russia, White Russia, Ukraine, Volhynia, the Caucasus, Bukhara, Georgia, Dagestan, the Donetsk Basin—flour for matzah cannot be found,” he wrote. “ ... This year marks a new era in the lives of the Jews of Russia, a bitter era, one that has not occurred since the beginning of this deluge of suffering and troubles—G‑d should have mercy—and at this time the question of kimcha dePischa [“flour for Passover”] is a burning question.”7

The Soviet grain shortage was not unintended. In a process that began slowly in 1925 and now, at the end of 1928, was picking up steam, Joseph Stalin was forcing through his national collectivization campaign and introducing his first Five-Year Plan for the economy. Farmers and peasants who had worked the land and fed Russia for generations were being forced into state-run collectives, with countless arrested, exiled or executed for resisting or to make an example for others. Productivity inevitably plummeted, bringing about food shortages, but it was not an accident.8

“Coercion was the only way to attain wholesale collectivization,” writes historian Stephen Kotkin about Stalin’s position, which he took as a believing Marxist-Leninist. “The extreme violence and dislocation would appall many Communists. But Stalin and his loyalists replied that critics wanted to make an omelet without breaking eggs.”9

Into this crisis stepped Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, 48 years old at the time. He had become the leader of Russian Jewry with the passing of his father nearly nine years earlier, suffering greatly at the hands of the Bolshevik government for his leading role in reinforcing traditional Judaism during its time of greatest despair. Now, the Rebbe insisted that the ancient mitzvah of assisting needy Jews with Passover supplies, matzah specifically, titled in Aramaic as maot chitim (“wheat money”) or kimcha dePischa, would be needed more than ever in the land where the force-building of socialism was underway. He noted that not only was this a spiritual concern, but a material one: Almost all of the country’s Jews desperately sought matzah, and hundreds of thousands hanging between life and death would refuse to eat chametz on the holiday, thus placing their very survival at risk.10 Rabbis and Jewish leaders throughout the Soviet Union, including a specially formed emergency matzah committee in Moscow, were sending messages begging for help.

On Dec. 30, 1928, the Rebbe called a meeting with his eldest son-in-law, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gourarie, known as the Rashag, and Mordechai Dubin, a wealthy and influential leader of the Riga Jewish community and member of the Saeima, Latvia’s parliament, as well as a devoted Lubavitcher Chassid, informing them of his plan to spearhead an international aid campaign to send matzah and flour into the Soviet Union for distribution among all its Jewish centers.11 The Bolsheviks had never allowed such a thing before, nor did anyone knowledgeable with the situation believe they would. “Dr. Rosen,” wrote a JDC staffer at the time, referring to Dr. Joseph Rosen, the JDC’s longtime representative in Moscow, “stated that bulk shipment of matzoths could not be made to Russia.”12

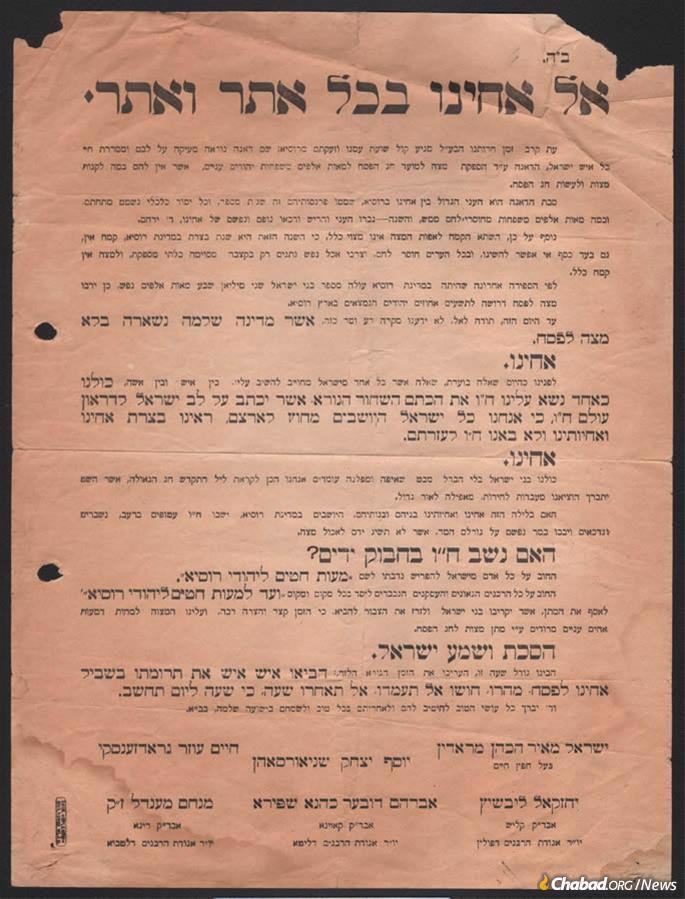

“Until this day, thank G‑d, we have not known a situation as evil and bitter as this,” the Rebbe wrote in a public proclamation asking Jews around the world for assistance—an appeal that was co-signed by the greatest Jewish luminaries of the day: Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan, renowned as the Chofetz Chaim; Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, the head of the beit din in Vilna (then Wilno, today Vilnius); as well as the heads of the rabbinical committees of Poland, Lithuania and Latvia. “There is a whole country that will be left without matzah for Passover!”13

In the coming months, the Rebbe would overcome Soviet policy and bureaucracy, European naysayers and American apathy to see the project to success, delivering 28 train cars of matzah and 5,689 packages of matzah flour into the Soviet Union for Passover.14

Climax of Suffering

By the end of 1928 and the beginning of 1929, the Jews of Russia had been through a great deal, the “deluge of suffering and troubles” alluded to by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak that had begun with the outbreak of World War I only 15 years earlier. The war had devastated the Jewish shtetls and towns of Ukraine and White Russia, bringing with it violence and privation, and unleashing a terrible refugee crisis. These events dovetailed with the 1917 Russian Revolution and the seizure of power that October by the Bolsheviks, the most extreme of the revolutionary groups. The Bolsheviks’ coup was followed by the bloody Russian Civil War, which pitted the disparate anti-Communist opposition White Army forces against the emerging Communist Red Army.

Although there were cases of Red Army abuses, it was the White Army and aligned Cossack groups, as well as Ukrainian nationalist bands in particular, who brutalized the Jews most, raping and pillaging as they tore through defenseless Jewish villages and making infamous the names Denikin and Petliura in Jewish memory.15 The Jews of western Ukraine suffered similar inhumaneness at the hands of Polish forces. Between 1918-21, more than 2,000 pogroms took place, mostly in Ukraine, leaving 150,000 Jews dead, either killed directly or due to disease, and half a million homeless.16

As the Bolsheviks fought off the White Army and solidified control over the country, they began doing just what they had campaigned on: constructing a Communist society. This “involved the nationalization of the means of production and most other economic assets, the abolition of private trade, the elimination of money, the subjection of the national economy to a comprehensive plan, and the introduction of forced labor.” The result was economic disaster. As compared to 1913, industrial production fell by 82 percent and worker productivity by 74 percent. Cities emptied as people ran to the countryside in search of food, and the government responded by confiscating peasant “surpluses.” As the first signs of famine appeared, violent rebellions began popping up around the country.17

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak wrote in some detail describing each of these distinct eras and how despite it all the Jews of Russia had, with great difficulty and “by the sweat of their faces,” been able to obtain matzah for Passover. “Due to the self-sacrifice of rabbis and community leaders in each and every city [throughout these years] they procured flour to bake a limited quantity of matzah, and despite everything—thank G‑d—not one community or congregation was left without matzah.”18

In an attempt to quell unrest and gain a more secure footing, in March of 1921 Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin introduced new measures of economic liberalization called the New Economic Policy, or NEP, which allowed a limited market economy. While it was a tactical and temporary retreat from Lenin’s hardline Marxist beliefs, things turned around on the ground and food once again began appearing on tables. There was even a new quasi-moneyed class created—a concept antithetical to Communist ideology, and a bone of contention between Lenin and his opposition on the left—called NEPmen.

“During the years of … NEP … flour for matzah could [easily] be found,” the Rebbe explained, “there were even large sums of money collected for the support of the poor.”19

In April of 1922, Lenin appointed Stalin to the powerful position of general secretary of the Communist Party, and a month later experienced a debilitating stroke. By the time Lenin died two years later, Stalin was in position to seize control. He skillfully played his opponents off of each other, with his “complete political triumph over the opposition” coming in December 1927.20 From that point, in the name of his Marxist ideals and while pursuing a personal dictatorship, he would order the murder of millions of people and change the course of history.

Stalin’s first step in breaking the will of the people would be one of his most ruthless. It began slowly, almost immediately after he took power, and “by 1928, he had decided that 120 million peasants in Soviet Eurasia had to be forcibly collectivized.”21

‘Will We Find Matzah This Year?’

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s fear that the Jews of Russia would not have matzah for Passover was not based merely on religious feeling, but stemmed from a deep understanding and empathy for the Russian Jewish soul. Passover was, and throughout the Soviet period remained, the Jewish holiday most Soviet Jews remembered and cherished.22

“One who knows well … the nature and character of Russian Jewry can openly and confidently say that you will not even find 10 percent who eat chametz on Passover, G‑d spare us, while 90 percent seek out matzah,” the Rebbe wrote. “Regardless of the philosophy or worldview of each individual, whether a religious view, or nationalist, or from the habit of or love for the ways of their fathers, there are 2,500,000 Jews who plead for matzah … [and ask] ‘Will we find matzah this year?’ ”23

In his description of the prior 15 years, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak wrote about the hardships that began with Stalin’s curtailing of NEP and the gradual end of private enterprise. He describes a man of means who in 1922 was able to support local causes, but by 1924 had died penniless and was buried at the expense of the community. Almost immediately, finding matzah became difficult. But now the Jews of the Soviet Union were entering a new era—one that would eclipse everything that had come before. The question of obtaining matzah could no longer be left to communal leaders remaining in Russia, but desperately needed the help of international Jewry.

Aside from the war on religion that had continued to be fought harshly throughout the decade by Soviet authorities—NEP policy, in fact, went hand in hand with “intensified political repression”24 —when synagogues were closed, mikvahs destroyed, and rabbis and shochetim (ritual slaughterers) arrested, Stalin’s policy of collectivization, which formally commenced in October 1928, was designed to break the people. Instead of attempting to avoid a famine, he welcomed it, and even as Soviet harvest figures fell he blocked the importation of grain from abroad.25 The question now was twofold: How would the regime react to a mass international campaign to send matzah and flour in to the country as a form of assistance? And would world Jewry respond to the call for help?

The first step in the matzah campaign, it was decided at the initial meeting in Riga, would be for Mordechai Dubin to approach the Soviet ambassador to Latvia to request that a certain number of train wagons bearing flour or matzah be permitted into the Soviet Union. Dubin, true to his punctilious nature, met the next day with the ambassador, who promised he would do all within his power to help. A few days later, Dubin and Gourarie together met with the Soviet trade representative in Latvia who told them the request had been sent in writing to Moscow, and there would be a response in the coming weeks.

Week after week went by, with Dubin and Gourarie consistently requesting an update from the Soviet embassy and being told there was still no response. On Jan. 21, 1929, they were again received by the trade representative, who said he was traveling to Moscow and would be able to clarify things there for himself.

Meanwhile, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak sent a detailed proposal for a matzah campaign to Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, the Chofetz Chaim and Rabbi Dr. Meir Hildesheimer—a prominent Orthodox rabbi in Germany and the director of the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary—asking them for their feedback. All three responded that they would gladly support Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s campaign. The Rebbe then wrote the text for an appeal which he, Rabbi Chaim Ozer and the Chofetz Chaim signed. Within weeks, Rabbi Yechezkel Livshits of Kalish (Kalisz), Rabbi Avraham Dovber Kahane Shapiro of Kovno (Kaunas) and Rabbi Menachem Mendel Zak of Latvia had signed on, too. This call for support was widely published in Jewish newspapers around the world.26

The chief rabbis of England, France, Holland and Belgium would soon lend their support as well.27

An American Shrug

Even as the question of Soviet permission hung overhead, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak began sending messages to the JDC in New York—the united front of the three largest Jewish relief organizations in America, making up the establishment of Jewish philanthropy in the country—asking them to financially support the matzah campaign. The response from a number of influential leaders at the JDC was underwhelming. They felt that the work of JDC’s Agro-Joint, which established and supported Jewish agricultural settlements in Ukraine, and into which they ultimately sank $16 million (a value of $238 million in 2019) before the Soviets shut the project down in 1938,28 would be placed at risk if they had any formal connection with the matzah campaign. They had also stopped funding Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s religious efforts in the Soviet Union in early 1928—at least partially because they feared the illegal nature of his work—and some on the committee felt that meant their policy was not to support any religious work in the Soviet Union at all.29

At the same time, however, Max Manischewitz of the Manischewitz Matzah Company heard of efforts to send matzah into the Soviet Union and turned to the JDC offering to help. At the JDC, the decision was made that whatever the case may be, they could not formally support the campaign. What they could do was have Rosen in Moscow inquire with authorities as to whether it might be permitted.

Not everyone at the JDC was happy with this stance.

“While I fully understand that the Agro Joint has nothing to do with relief in Russia and is not supposed to handle it,” wrote the organization’s Adler to its secretary, Joseph Hyman, “I cannot understand why we should be so terribly tender in dealing with a country which has not sufficient flour of its own but will only permit the flour to be introduced surreptitiously.”30

Hyman responded by laying out their concerns, explaining that they feared Jewish Communist groups—i.e., the Yevsektzia, the Jewish sections of the Communist Party—might embarrass them by delaying delivery of matzah until after Passover. They also worried that due to the general lack of white flour in Russia, “the Government might deem it inexpedient to permit any special group of the population to have white flour products, particularly on religious grounds, while the rest of the population could secure white flour only on the prescription of a doctor.

“These are some of the elements of the situation which make it difficult for the J.D.C., as you appreciate, at this time to have any official relationship with the matter.”31

In Riga, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak was almost immediately made aware of these developments in New York, writing to Rabbi Chaim Ozer in Vilna on Jan. 24 that he had just received bitter news via telegram that the JDC had met regarding aid for the matzah campaign a day earlier and “With regards to the budget, there is no hope.”32

“This bitter news made a strong impression on me,” he wrote less than a week later to Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum, the head of the Central Relief Committee, a member of the JDC executive,33 as well as head of the Agudath Harabbonim in New York. The Rebbe had since received news that there was a possibility of help, but he expressed shock at the initial blanket dismissal. “Is it possible that our brothers in America see the pain in the souls and bodies of their brothers and hear their pleading and they will not help them? I did not believe what my ears heard … ”34

By this time, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, Rabbi Chaim Ozer and Rabbi Meir Hildesheimer had formally created a central committee for the matzah campaign, with Gourarie as their representative. In the coming time, two committees would be formed under its auspices: a financial committee in Berlin, to which any funds collected would be routed; and a logistical one in Riga, where the matzahs would be baked and sent into the USSR.35

“Help for this cause can only come from abroad and it is the duty of honor of the Jews of other countries to provide for this … ,” the Rebbe wrote directly, in German, to Adler on Feb. 1. “We see no other way out of this desolate situation than that matzos from abroad be imported to Russia for the Jewish population … Russian Jewry will never forget your service … ”36

Soviet Bureaucracy

Time was ticking and the holiday of Purim approaching. With Passover less than three months away, no response was forthcoming from the Russians. A second front had to be opened, and Dubin and Gourarie traveled to Berlin, where Hildesheimer had assembled some of the country’s most influential Jewish figures including Leo Baeck and Oskar Cohn. The members of the Berlin committee, along with the JDC’s representative in the city, Bernard Kahn, ultimately played key roles in the operation’s success.

In Berlin, the delegation approached the Soviet ambassador to Germany, Nikolai Krestinsky, again requesting Soviet permission, with Krestinsky—an Old Bolshevik whose one-time support of Trotsky would lead to his execution less than a decade later—promising he’d have an answer soon.37

From Berlin, Dubin and Gourarie went to London and Paris. While they were at first greeted warmly and enthusiastically, with representatives of the umbrella Jewish organizations promising financial assistance, it seems that one prominent donor insisted that the plan to send matzah was impossible, using his influence to cool down the initial willingness of these organizations to help.38 Despite this, both these communities created local committees to collect funds for the project. Similar committees were formed in Holland, Finland, Copenhagen, Switzerland, Poland, Belgium—which Gourarie and Hildesheimer visited together—the land of Israel (where it was publically supported by Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Kook, chief rabbi of Palestine; Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, head of the Eida HaCharedis; and Sephardic chief Rabbi Yaakov Meir) and the Alsace region of France. Committees were even formed in Shanghai and Harbin, China.39

“A desire to aid the Jewish families in Soviet Russia who require matzoth for the forthcoming Passover holiday led the Harbin Jewish community, composed mainly of refugees from Soviet Russia, to forward $1,000 to the Berlin Matzoth Committee … ” reported the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) on April 7, 1929. “The action … was prompted by reports … telling of the efforts being made throughout the world to supply Russian Jews with matzoth … ”

Yet in mid-February, the Soviets had still not granted permission for the importation of matzah.

“Berlin Jewish Committee in connection with Schneerson [sic] trying get permission mazzoth import,” Kahn cabled to the JDC in New York on Feb. 15. “Answer expected next week.”40

As they waited, a false report appeared in Warsaw’s influential Yiddish-language newspaper, Haynt, that permission had been explicitly denied, this setting off a flurry of worry among the various matzah committees, with the Rebbe even receiving a mournful telegram from the Manischewitzes, saying, “We have done all we could with regards to sending matzah to Russia … ”41

That same day, Feb. 22, Hildesheimer called Adler at the JDC in New York begging him to help stem the false news and noting that it had already done grave damage. Adler even drafted an item for the Jewish Daily Bulletin to that effect, but by that time another news report had appeared in Europe, in the JTA, stating perhaps optimistically that the Russians had on the contrary given permission (although they still had not).42

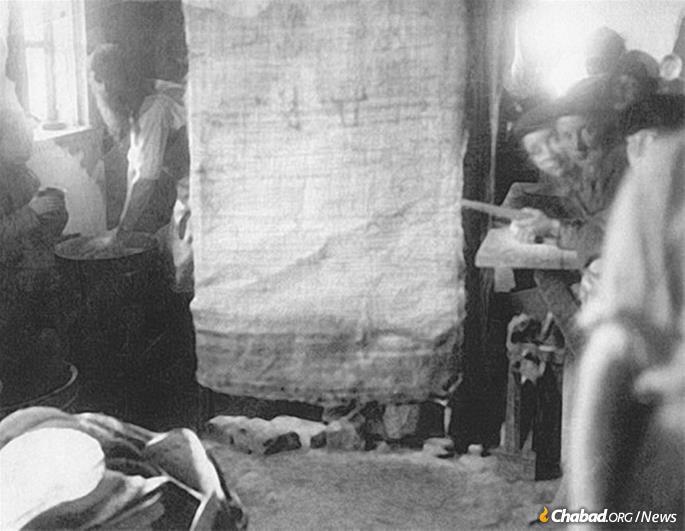

Despite this mini-crisis, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak began leading discussions with three matzah bakeries in Riga to straighten out all the details of matzah-baking, which would need to commence immediately once permission was, if at all, received. He then traveled to Berlin to meet with the Hildesheimer committee, as well as Jewish representatives from London, Basel, Vienna, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Warsaw where it was decided, among other motions, to immediately prepare 10 wagons worth of matzah.43

On the morning of March 6, 1929, Hildesheimer again met with Krestinsky, with the latter saying that the Soviet government had officially granted permission for 50 train cars of matzah to be imported to the Soviet Union, but that the instructions had been sent to the embassy in Latvia. Dubin, by then back in Riga, arrived at the embassy there the very next day, informing them of what had been communicated from Berlin. The Soviet trade representative in Riga, however, knew nothing of it.44

“It is difficult to describe how hard it is to have a discussion and to reach a decision in anything with Soviet bureaucracy,” Gourarie later wrote. “This is their method: Every day they say, ‘We have no answer;’ ‘This is beyond my authority;’ ‘I must telegram Moscow;’ ‘There is no answer from Moscow;’ ‘The answer is in Riga;’ and in Riga the same scene plays itself out, except that from there the matter is referred back to Berlin, and every day telegrams are exchanged from Moscow and to Moscow, and no clarification can be reached.”45

On Wednesday, March 13 (Rosh Chodesh Adar II)—just 42 days away from Passover, a week after the initial conditional good news from Krestinsky and after days of repeated visits to the Soviet embassy in Riga—Dubin once again met with the Soviet trade representative who told him that since they had still not received instructions from Moscow the embassy had decided to allow them to send five wagons of matzah—three to Moscow, one to Leningrad and one to Minsk—with a modest duty of five kopeks per kilo. The discussion of duty, which had been an open question during the previous weeks of organization and fundraising, would yet play a role in the matter.

At 1 a.m., Dubin returned from the Soviet embassy with the good news. Preparations in Riga were spearheaded by Rabbi Eliyahu Chaim Althaus, Rabbi Mordechai Cheifetz and Shimon Wittenberg (who would later join Dubin in Latvia’s parliament), as well as a group of young volunteers, and they began working immediately. By Thursday, two wagons were already on their way into the Soviet Union.46

But the Soviet representatives had jumped the gun. The Soviet Union, badly in need of hard currency,47 was going to allow the matzah in, though the Jews would have to pay a price. On Thursday night the Soviet trade representative telephoned Dubin and told him that he had made a mistake, and if the wagons had not yet been sent to please hold off, as he was awaiting special instructions from Moscow. Dubin, a powerful political operator in the country, refused to back down, telling him that if he regretted it, then now Dubin knew that this had just been a matter of politics. Three hours later the Soviet official conceded the point to Dubin, allowing the first five wagons to proceed to their destinations.48

In Riga, another five wagons were prepared immediately, but then came news from Berlin. The Russians had granted permission for 50 wagons of matzah, but there was a catch: They would need to pay the luxury duty of two rubles per kilo.49 Each wagon could hold approximately 5,000 kilo of matzah, 250,000 kilo all together, and in 1929 one gold ruble (the regular Soviet ruble was not convertible to foreign currency) equaled approximately 51.7 U.S. cents.50 This brought the sum needed to approximately $130,000 for duty alone, the equivalent of nearly $2 million in 2019.

But What About the Money?

Although funds were trickling in from throughout the world, the matzah campaign’s financial committee in Berlin was waiting for some sort of appropriation from the JDC. For his part, Alder sent a telegram to Kahn in Berlin requesting him to communicate (carefully) with Rosen in Moscow, and ask whether “he can apply any part his new appropriation palliative relief in matzoth purchase through kehillahs or mutual aid societies,” before asking whether the “Hildesheimer committee perfected any plans,” adding: “preferably his committee should take charge of this entire matter.”51

Kahn responded on March 6 that Rosen needed his new appropriation for Passover relief within the Soviet Union and could not spare any money for matzah purchase outside of it. “Hildesheimer committee has permission to import fifty carloads matzoth but not duty free,” Kahn cabled. “For this matzoth problem $45,000 needed of which $20,000 will be collected Europe. They urge you appropriate $25,000 and ask for cable reply.” The Berlin committee, added Kahn, had also decided that baking matzah in Riga would be cheaper and simpler than shipping Manischewitz’s specially priced matzah from New York, bringing to an end their role in the matter.52

During this time, the Rebbe himself cabled the JDC asking for the $25,000 towards the wagons, but they remained unmoved.

“Officers other members committee indicate no possibility securing new allotment requested by Schneersohn for matzoths,” wrote Adler in the name of the JDC (the telegram was drafted by others and signed by Adler). “Please so advise Schneersohn Hildesheimer making clear Passover relief Russia available only from what Rosen can grant … ”53

Kahn, who seems to have been supremely devoted to the cause of maintaining Jewish religious life in Russia—and who remained a staunch defender and supporter of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s, despite the change of heart of many at the top of his organization—responded in his own fashion: by granting money from his own funds.

“Sorry you cannot make new allotment for matzoths,” he telegrammed on March 9. “Non-participation JDC may bring matzoth action to complete failure[.] Other donors may withdraw their donations therefore have granted $10,000[.] Will discuss [with JDC chairman Felix] Warburg [and] Adler how to cover new appropriation.”54

Contrary to what has been written elsewhere before, this would be the only JDC appropriation to the matzah campaign of 1929.55

Back in Europe, negotiations with Soviet diplomatic staff were taking place in both Berlin and Riga, as well between the Russian emergency matzah committee in Moscow and trade officials there, to lower the demanded duty. Finally, an agreement was reached marking the duty at 50 kopeks a kilo, all of it made payable only in hard currency, or valyuta in Russian.56

Still, the price was a high one—100 percent of the cost of the matzah itself—and a number of donors began suggesting abandoning the idea of sending in matzah and instead send cash so that Jews in Russia could purchase the matzah that they needed. The Rebbe, who throughout this period was in constant coded correspondence with rabbis throughout the Soviet Union—including, among others, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, chief rabbi of Dnepropetrovsk and the father of the future Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory; and Rabbi Shmarya Leib Medalia, the chief rabbi of Vitebsk—was strongly against this idea, arguing that 1.) the Jews of Russia were seeking matzah precisely because there basically was none; 2.) such help and assistance from their brethren abroad would lift Russian Jewry’s spirits; 3.) and altering the plan from sending matzah to sending currency would weaken the entire campaign, which by then had picked up steam.57

The matter was settled once and for all when Rosen in Moscow telegrammed the committee in Berlin that matzah and flour in the Soviet Union were so expensive that it was cheaper to send the matzah from abroad despite the high duty, than to purchase whatever was available within Russia.58 And so, the trains started rolling into the Soviet Union: 23 from Riga and five from Berlin.

![A receipt for a British 50-pound contribution to the matzah committee. The German letterhead at the top left and the Hebrew stamp in the center both state: "Committee to Send Matzah to the Jews of Russia, Riga, Latvia." From the top, the receipt is signed by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, Rabbi Meir Hildesheimer, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gourarie, [Avigdor?] Volshonok,Mordechai Dubin and Avraham Sobolevitch, all members of the Riga committee. (Photo: Jewish Educational Media/Early Years.) A receipt for a British 50-pound contribution to the matzah committee. The German letterhead at the top left and the Hebrew stamp in the center both state: "Committee to Send Matzah to the Jews of Russia, Riga, Latvia." From the top, the receipt is signed by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, Rabbi Meir Hildesheimer, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gourarie, [Avigdor?] Volshonok,Mordechai Dubin and Avraham Sobolevitch, all members of the Riga committee. (Photo: Jewish Educational Media/Early Years.)](https://w2.chabad.org/media/images/1087/vwbU10874597.jpg?_i=_n504BC99DD0473598AAE3BCDC5D75568D)

While the JDC had been reticent to contribute their own funds to the project, they did agree to channel money raised in America through their accounts into Berlin, where Hildesheimer could withdraw it. Teitelbaum’s Agudath Harabbonim launched a few rounds of appeals via the two largest New York Yiddish dailies, Der Tog (“The Day”) and Der Morgen Zhournal (“The Jewish Morning Journal”), and the response was overwhelming. In a short period of time, the Agudath Harabbonim’s appeal raised $50,000, all of which was sent to Berlin for the campaign.59

Victory at Hand

Anti-religious forces within Russia did not appreciate the external campaign, nor the internal demand, for matzah, and the Yevsektzia’s newspapers spewed broadsides against the rabbis of Russia. The Oktyabr (Belarus) demanded to know how Russian rabbis established contact with foreign organizations in the first place.60 The Yevsektzia also complained that while for some reason when tractors were ordered from abroad Soviet customs officials took their time, now all of a sudden matzah was arriving on a daily basis.

As could be expected, despite the agreements that had been made by one branch of the Soviet government, at least on one occasion during the campaign customs officials in Russia held up multiple cars of matzah and demanded the full luxury tax of two rubles per kilo be paid, four times the 50 kopeks agreed upon. “Negotiations are now under way between the Moscow Kehillah leaders for the release of the matzoth,” reported the JTA on April 7.

Ultimately, by April 9 it was known that all the wagons had made it through, and were distributed in Moscow, Leningrad, Minsk, Kharkov, Vitebsk, Cherson, Dnepropetrovsk, Kremenchug, Zhitomir, Berdichev, Gomel, Bobruisk, Shepetivka, Kiev, Rostov and Chernigov, with each of the cities distributing the matzah even further out to their surrounding towns and villages.61 In all, it seems, 125,000 kilo of matzah was baked and sent from Riga and nearby Dvinsk (Daugavpils), with another 15,000 kilo being sent from Berlin. Additionally, 5,689 packages, which contained about 5 kilos of flour each, were sent to some 2,000 different addresses in 400 localities. Towards the end of the campaign the committee secretly began sending cash assistance as well. In all, the matzah campaign of 1929 cost $88,000, or more than $1.3 million today.62

Remarkably, all of this took place even as Stalin was forcing through his violent collectivization plan. “No concessions in grain procurements,” he wrote that year. “Hold the line and be maximally unyielding!” warning that they could not have pity nor “vacillate one iota from our plan … ”63 Yet a concession for matzah and matzah flour had, for some reason, been made. On April 23 the 16th party conference of the All-Union Communist Party (bolsheviks)64 opened in Moscow. That evening countless Russian Jews around the country gathered with a candle, feather and bag to perform the traditional bedikat chametz, the search for chametz in their homes; Passover began the next evening, on April 24. The 16th conference, during which a maximalist version of Stalin’s Five-Year Plan was ratified,65 coincided almost to the day with that year’s Passover, when the Jews of Russia were able to have matzah because of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn.

The Soviets knew precisely who Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak was, and yet he had come out on top. In a letter dated May 7, 1929 (27 Nissan, 5689), the Rebbe responded to a questioner asking what the purpose of the campaign had been. The Rebbe noted the miraculous nature of the whole campaign, how all the matzah had been sent in to Russia in a period of just 26 days, and how when the three Riga-based shipping expeditors came back with receipts for the flour packages, they added up to precisely 5,689, the same number as that year on the Jewish calendar. Most of all, it showed the depth of Jewish unity.

“The matzah campaign demonstrated the true makeup of the traditional Jew [Hayehudi ben Yisrael saba], that the Jewish people lives beyond the limits of nation and aspirations of party,” he wrote. “The matzah campaign brought on its wings an awakening of the spirit, and warm regards to our brethren in Russia from their brothers around the world and the reaches of the earth … ”66

Join the Discussion