A single statistic tells the tale: With a prison population of nearly 2.2 million people, the United States—home to just 4.4 percent of the world’s population—holds around 22 percent of the world’s incarcerated individuals, and has the world’s highest per capita prison population, followed by El Salvador, Turkmenistan, Thailand and Cuba. Granted that some countries (Cuba, China, North Korea, Iran) are most certainly underreporting their prison statistics, that still doesn’t leave the United States, a beacon of hope and freedom since its founding, in very good company. It wasn’t always this way; in the last 40 years, America’s incarcerated population has increased by 500 percent, leading to what is now commonly referred to as mass incarceration.

In a country deeply politically divided between right and left, few issues of the day draw as much broad consensus in the United States as the need for transformational criminal justice reform that would reduce the incarcerated population while enhancing safety. A key to the solution may come from the growing concern being expressed by voters. The American Civil Liberties Union’s Campaign for Smart Justice recently found that although traditionally viewed as a “progressive” issue, 78 percent of likely voters, including 72 percent of Republicans, are more likely to vote for a candidate who supports criminal justice reform. The problem has become so endemic that—once too dangerous to address lest a candidate be accused of being “soft on crime”—it is now no longer the third rail of American politics.

These days, many people from across the political spectrum and at all levels within the criminal justice system are working hard to bring about change. On June 17-18, some 400 of them—leading jurists, including federal and state judges, district attorneys, members of Congress, probation and parole officers, academics and activists—gathered in Manhattan for the landmark Rewriting the Sentence summit on alternatives to incarceration. Hosted by Columbia Law School, the summit was organized by the Chabad-Lubavitch-affiliated Aleph Institute, the leading Jewish organization caring for the incarcerated and their families. Partners included the American Bar Association Criminal Justice Section, the ACLU, the American Conservative Union Foundation, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and R Street, among other organizations.

“This is an opportunity to gather different constituencies in the criminal justice system to try to really put the humanity back into sentencing and to make sentencing more proportionate to mitigate the harm,” U.S. Circuit Judge Bernice D. Donald of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals and chair of the summit told Chabad.org. “As Rabbi [Sholom] Lipskar [founder of the Aleph Institute] mentioned, the sentencing process doesn’t just affect the defendant, but it affects the family and the whole community. Sometimes, we are, through the sentencing process … disregarding the humanity of the person and the potential productivity of that person. We can’t incarcerate our way out of our issues.”

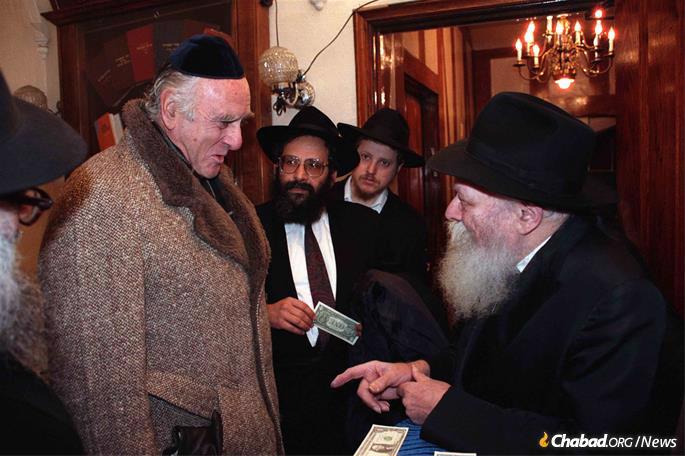

Indeed, the fact that society can neither police nor incarcerate its way out of the deeply rooted underlying societal dysfunctions that result in crime was a constant theme in the teachings of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, who directed Lipskar to establish the Aleph Institute back in 1981. At the time, crime rates were rising in the United States, and by the end of that decade new Federal Sentencing Guidelines—coupled with strict mandatory minimum sentences for a wide swath of crimes, most of them nonviolent offenses—were the response.

The Rebbe, whose 25th anniversary of passing will be marked on Gimmel Tammuz, which corresponds to July 6 this year, consistently rejected such an approach, stating unequivocally that a foundational moral education was the antidote to the root problem. Prisons, the Rebbe noted on a number of occasions, could only be useful if they first and foremost underlined the essential humanity and potential for good of each incarcerated individual—that they are “just as human as the prison guards,” the Rebbe stressed in a 1976 talk. The goal of incarceration, he said, should be to re-educate and rehabilitate those convicted of crimes, preparing them to re-enter society as soon as possible so they could return to their individual missions in the world.

In those early days of the Aleph Institute, Lipskar, young and inexperienced in the alternate universe that is the prison system, met with Judge Jack B. Weinstein, former chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York. Weinstein, who still serves on the bench, recognized the Rebbe’s vision. “Your Rebbe is ahead of the curve,” he told Lipskar.

In 1989, as Weinstein prepared to testify before the Federal Sentencing Commission, he came to the Rebbe together with Lipskar, telling the Rebbe that he would be sharing his views on imprisonment with the commission.

“You will support my views also, not only report my views?” the Rebbe asked Weinstein, who answered in the affirmative.

“May G‑d Almighty bless you to go from strength to strength,” the Rebbe continued, “and to reach the time when there will be no prisons, only preventative education to prevent people from going astray from the right way.”

“They didn’t listen,” a still-spry Weinstein recently told Chabad.org, referring to the Federal Sentencing Commission.

‘An Extremely Serious Problem’

In the context of the Rebbe’s revolutionary outlook on the very concept of criminal justice, Aleph has been at the forefront of alternative sentencing—pioneering, for example, the use of electronic monitoring.

Aleph’s goal has always been to find a better way to balance society’s need for safety and justice than merely by sending more people convicted of crimes away for longer terms of imprisonment, which had resulted in America’s record incarceration rates. The organization’s activism has helped change the fate of hundreds of thousands of individual prisoners, both Jews and non-Jews; in fact, Aleph played a key role in the successful passage of the 2018 First Step Act, the most consequential overhaul of the U.S. criminal justice system in a generation. The Rewriting the Sentence summit was yet another crucial step towards the Rebbe’s vision of a better and more just world, and the realization of the concept that every human being has a Divine spark within them and a singular role to play in this world.

“We are dealing with an extremely serious problem because we are not dealing with a few hundred people, we’re dealing with millions … ,” explained Lipskar in his opening remarks at the summit. The criminal justice system incarcerates more than 2 million people. Even once they are released, they face more than 170 federal restrictions on their freedom, called “collateral consequences,” and on average 1,000 state “collateral consequences,” including limitations or prohibitions on voting, public education and housing, and businesses and occupational licenses.

The devastating impact of incarceration extends to the estimated 10 million children in the United States who have experienced parental incarceration—an ordeal that statistically has an acute impact on their own chances of ending up within the criminal justice system.

“ ... We’re talking about millions of children and families who are totally discarded, not dealt with properly,” stressed Lipskar “They don’t have the social support that’s necessary, the educational support that’s necessary. They’re looked down upon; they’re embarrassed about their position.”

The solution, he and others repeated over the next two days, is not a minor fix.

“We need to rethink it,” he stated.

The Divine Spark

Judge Jeremy Fogel, immediate past director of the Federal Judicial Center, spent 37 years on the bench, serving at the local, county, state and, most recently, as a U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of California. He also served as director of the Federal Judicial Center, the research and educational agency of the judicial branch of the federal government, from 2011 until his 2018 retirement from the bench. At that position, Fogel, who delivered the summit’s keynote address, oversaw the center’s work which includes what is colloquially termed “Baby Judges School,” a crash course offered to newly appointed federal judges where they learn the fundamentals of the awesome responsibilities their lifetime appointments confer on them. While it’s not mandatory, the vast majority of new federal district judges take the course.

Recognizing the vital importance of Rewriting the Sentence, the Federal Judicial Center funded travel for some 25 federal judges to attend.

Now serving as the first executive director of the Berkeley Judicial Institute, Fogel’s wide-ranging address focused on the fundamental changes the American criminal justice system requires. But he also warned of the difficult road ahead, and the necessity of realistic expectations and recognizing that not all ideas are in fact effective or good ones.

In setting the tone of the summit, Fogel recalled his school days at Columbia, where he had encountered the Jewish concept of the Divine spark in a religion class he took.

“ ... There is a Divine spark within every human being ... , a spark that is present within every genuine connection between people ... ,” said Fogel. “ ... When I first heard about the Aleph Institute and its commitment to transforming the way we think about criminal justice, particularly our approach to incarceration, it was deeply reassuring to encounter the Divine spark again. It is a concept that affects not only the way we see people, but also how we relate with them. A truly transformative approach to criminal justice requires not only an abstract respect for every person, but also a genuine openness to meeting each person where he or she is and experiencing our common humanity … .”

In the Rebbe’s pioneering formulation of this idea, he explained that the goal of prison—although not a consequence ever prescribed by the Torah—“should not be punishment, but rather to give him the chance to reflect on the undesirable actions for which he was incarcerated. He should be given the opportunity to learn, improve himself and prepare for his release … .”

Over the Aleph summit’s two days, dozens of panelists doing innovative work in all areas of the criminal justice system presented alternative educational programs, including drug rehabilitation, job training and restorative justice initiatives that help those convicted to understand the consequences of their actions by meeting with victims and families, and engaging in meaningful community work. And yet, the Rebbe always pointed out—and as Fogel echoed—that education could not do its job without the underlying respect for and acknowledgement of the human soul.

“In order for [education and improvement] to be a reality, a prisoner must be allowed to maintain a sense that he is created in the image of G‑d,” the Rebbe stressed. “He is a human being who can be a reflection of G‑dliness in this world.”

It has taken the U.S. criminal justice system decades of devastating experience and loads of data to start taking this core concept seriously.

“With few exceptions,” Fogel stated, “people who have spent time in prison are most likely to succeed outside only if they can find a deeper place within themselves, only if they can see themselves and the people around them in a different way. They need to gain, or regain, a sense of their intrinsic worth, not as a vague idea, but as a physical and spiritual reality … .”

New Approaches to Sentencing and Parole

The term “penitentiaries” as a name for prisons is unique to the United States, tracing back to the beginning of the 19th century. It was meant to connote places of penitents, where convicted individuals could consider and repent for their past actions before returning to society. Instead, in recent decades, prisons have become punitive facilities. The probation and parole system has experienced a similar trajectory; going from an institution meant to either keep a person out of prison or ease re-entry back into society to a system that all-too-often sends those convicted straight back to the facilities from which they had been released or which probation was meant to avoid. Despite the stated goal of correction and rehabilitation, data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics show that within three years, a full 68 percent of released prisoners are rearrested.

In other words, the system’s not working.

But it’s not only the correctional facilities that are to blame; they are part of a much larger system that has grown and developed over time. Radical change—some activists are seeking to cut incarceration numbers by 50 percent, which, according to The Sentencing Project, would take until 2093 at current decarceration rates—means drawing together all elements of the criminal justice system.

Fogel’s keynote was followed by a panel of federal judges titled “Judicial Practices: Creative Approaches to Sentencing,” which was moderated by Aleph’s Rabbi Yossi Bryski, who directs the organization’s Alternative Sentencing Division, and whose panelists were Judge Fredric Block, U.S. District Judge, Eastern District of New York; Judge Virginia Phillips, chief U.S. District Judge, Central District of California; Judge Esther Salas, U.S. District Judge, District of New Jersey; and Judge Brooke Wells, U.S. Magistrate Judge, District of Utah. In an animated discussion, each presented alternatives to prisons they had successfully pioneered in their own courtrooms.

Wells, for example, spoke about mental-health courts set up in her district, while Phillips described her California district’s CASA program, or Conviction and Sentencing Alternatives, formed in 2012 via a partnership between the then-chief judge, the chief public defender and the then-U.S. State’s Attorney. Geared towards individuals whose criminal activity—limited most often to drug and financial crimes—belies an underlying issue, the program includes drug rehab, if necessary, community service and educational requirements. Designed to reintegrate offenders into society, successful graduates of CASA’s track one have their charges dismissed, while those on track two are sentenced to probation.

“I’m going to encourage everyone in this room to start incorporating a change within your own professional life … ,” Salas told the audience. Describing her sentencing process, Salas explained, “I want to come up with a sentence that is sufficient but not greater than necessary to address our concerns. I can tell you that if anyone says, well, these programs, they’re soft on crime. We’re talking about avoiding recidivism; protecting the public, and how do you do that? You do that by addressing the problem. … There’s changes that I’ve made, many more I’d like to try. But we have to try … .”

Block, who quipped that he was Judge “Feivel” Block when at an Aleph event, discussed collateral consequences at length, which are enacted by federal and state legislatures, and the need for both prosecutors and defenders to discuss pertinent consequences the convicted may face. Taking the state of Oregon as an example, he read out a partial list of collateral consequences that those convicted in the state faced, including being ineligible to be Black Bear Cougar agent for the department of fish and wildlife, ineligible for telemarketer registration, ineligible for an acupuncturist license and, crucially, ineligible to receive free public education, among many others—709 in Oregon in all.

“There are 94 district courts, only 24 with alternative sentencing programs ... where are the other 70 district courts that have not yet embraced any concept of alternatives to sentencing?” asked Block. “Hopefully, because of the Aleph Institute, it’s important to become aware of where we are at, how much further we have to go and to hope that when we gather here next time … , all of the judges of all of the district courts in the United States will have embraced concepts of alternatives to incarceration.”

The Why of Crime

Sentences are rendered by judges, who have it within their power to experiment with alternatives to incarceration, and active conversations took place throughout the two days of the conference, notably during the interactive mock-sentencing workshop given by Judge Nancy Gertner, a former U.S. District Judge for the District of Massachusetts, and today a professor at Harvard Law School. Gertner has been working closely with Aleph for years.

During the judges panels, presenters spoke of their approaches—all of them underscoring the need to look at each case individually and each defendant as an individual. Yet mandatory minimum sentencing laws first enacted in the 1980s have often made this difficult, sometimes impossible. These minimums, dictated by Congress from Washington, D.C., often took the power to sentence on a case-by-case basis away from the judge, applying a one-size-fits-all solution to disparate individuals. The First Step Act has eased some of those burdens, and yet there’s still a long way to go.

The facts are that whether wittingly or not, harsh mandatory minimums have disproportionately impacted the African-American community. Until 2010’s Fair Sentencing Act, minimums for crack cocaine offenses, a drug more common in black urban areas, carried far more severe automatic punishments than powder cocaine, a drug more often found in white suburbs. Among other factors, this has contributed to a glaring racial disparity in the U.S. prison population.

Just as criminal justice reform in general is popular across the political divide, a later panelist, Udi Ofer, director of the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice, pointed out that 75 percent of all likely voters, including 67 percent of Republicans, were more likely to support candidates who pledged to reduce racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

Ofer’s panel, “Systemic Reform and the Role of Advocacy,” was moderated by Michael Troncoso, director of criminal justice at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and included Ofer, The Sentencing Project’s Kara Gotsch and Marc Levin, of the conservative-leaning Texas Public Policy Foundation and Right on Crime.

“I think at the end of the day, and [the ACLU’s] polling reveals this, there may be differences in language … ” with how those on the right and left discuss criminal justice reform, explained Right on Crime’s Levin, “but we all want to get to the same place of fewer people in prison, more public safety, more people working and taking care of their families. So I think that resonates just as well in Oklahoma as it does in San Francisco.”

Gertner’s presentation cut more closely to the roots of the problem. Before beginning her case study, She shared her belief that decreased incarceration was not a criminal justice goal any more than more incarceration was. She also noted that while sentencing guidelines have taken away much discretion from judges, more discretion was only a beginning towards an actual solution.

“Criminal justice policy has to do with the kinds of issues people have been talking about today, which is the ‘why?’ of crime, the ‘how?’ of crime, not just more or less ... ,” she said. While for judges, the key is “education.”

Think Different

The same way true reform goes beyond implementing changes within prisons and jails, and beyond the work judges do, every aspect of the criminal justice world has a role to play to create meaningful change. One summit highlight was a panel of three recently elected district attorneys: John Creuzot of Dallas County, Texas; Lawrence Krasner of Philadelphia, Pa.; and Rachael Rollins of Suffolk County, Mass. Krasner discussed changing the metrics by which his office measures success, focusing for example on the reduction of recidivism instead of the most common benchmark in the system: win rate.

Aside from the district attorneys, panels incorporated conversations on pretrial and probation—panels that included Christine Dozier, chief pretrial services officer for the district of New Jersey, and Mark Gjelaj, deputy chief U.S. probation officer for the eastern district of New York—and alternatives in the mental-health arena. Letitia James, attorney general of New York, also shared her own remarks.

Among the most moving moments was a conversation reflecting on the passage, and more importantly, on progress in implementation of the 2018 First Step Act, which sailed through both houses of Congress and was signed into law by President Donald Trump at the end of December. The co-sponsors of the House bill, Rep. Doug Collins (R-Ga.) and Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), were joined on stage by Matthew Charles, one of the first people released under the First Step Act.

Charles, today a criminal justice fellow at FAMM (Families Against Mandatory Minimums), received a 35-year sentence for selling crack to an informant, serving more than two decades in federal prison—where he turned his life around—before gaining early release in 2016. Federal prosecutors appealed his release, citing previous felonies, and an appeals court was forced to order him back to prison after he had been free for two years, ruling that he needed to complete his initial sentence. Charles returned to federal prison before once again being released in January of 2019.

“When Matthew came to see us in January, literally, when I hugged him, I cried,” Collins shared. “Because how many times do you actually put a piece of legislation—and I made this comment to the president, I said, ‘Mr. President, when you sign this bill, it’s not simply lines on the pages, its faces behind the lines’—and how many times do you get to hug the face? … This was a very special moment that should be celebrated and implemented … but if we’re not able to say we kept our promise on this part and get it implemented properly, it’ll be almost impossible to get to the next level.”

The First Step Act was spearheaded by a group of Chassidic activists led by Moshe Margareten, who nearly a decade ago teamed up with the Aleph Institute to promote transformational reform legislation that incentivizes educational programs by offering time-reduction and places a premium on human dignity. The congressmen on stage were well-aware of this fact, as was Charles, who, at the conclusion of the summit, ventured together with Margareten to the Rebbe’s resting place in Queens, known as the Ohel, to say thank you for the First Step Act, a direct result of the Rebbe’s vision that continues to inspire Margareten and the other Chassidic activists.

The Vision

A summit like Rewriting the Sentence, bringing together such a wide-ranging group of thought leaders and players in the criminal justice system, is rarer than an outsider might think, according to participants.

“A two-day conference like this is astounding. It’s an extraordinary achievement for everyone who was behind putting this together,” said Professor Doug Berman, an attendee and panelist who authors the widely read and cited Sentencing Law and Policy blog.

“There can be at times an inclination for people to just get tired of thinking hard about it. ‘I’m never going to solve the problem of crime, I’m never going to solve the problem of punishment, so I’m just going to follow the [sentencing] guidelines,’ ” Berman, who also teaches at the Moritz College of Law at The Ohio State University, explained. “That’s why these things are so important, to take folks who can sometimes get jaded, whether judges, prosecutors or defense attorneys—the system can grind you down just because of the challenges. So just to be able to be refreshed and see other people energetic and presenting ideas and eager to talk about their experiences can be an incredible change agent … .”

Among the future steps are new and currently progressing pieces of legislation at all levels, and pilot programs being launched. At the conference, Aleph’s Hanna Liebman Dershowitz also announced the creation of their newest initiative, the Center for Fair Sentencing, which will aim to be a clearinghouse for the best policy initiatives from around the country.

Aside from the broad political consensus on display at the summit, the common thread tying the entire conference together was the basic concept of the irreplaceable human soul championed by the Rebbe. A video of the Rebbe speaking about prisons had a palpable impact on the room—men and women who through experience have seen the Divine spark within each person flickering even in the darkest of places.

In the aftermath of John Hinckley’s attempt on President Ronald Reagan’s life in 1981, the Rebbe discussed the fact that if children are not given a moral foundation, a basic grounding in the idea that there is more to life than math, science, English and history—many individuals who go through the criminal justice system are not provided even that—then they will grow to feel they can outsmart their parents and the police, all to the detriment of society and even worse, themselves.

Society, the Rebbe stressed, cannot jail its way out of its issues. Each person is accountable before G‑d and thus important, and has an obligation to fulfill his or her mission in this world. Society must do everything to assist all of its members in fulfilling that mission, whether children in public schools (who would be helped, for example, by a Moment of Silence) or the incarcerated adults some children unfortunately one day become.

“The summit’s objective was to inspire the key decision-makers to think about the process differently, to appreciate the humanity of everyone in the system,” explained Rabbi Zvi Boyarsky, Aleph’s director of constitutional advocacy. “Participants had the opportunity to hear firsthand about programs that can really turn people’s lives around. These are really Torah values—ideas taught to us by the Rebbe and based on his values.”

“Teshuvah (return to G‑d through repentance) is essentially a matter of inner felt resolve,” the Rebbe wrote in a pre-Rosh Hashanah letter addressed to prisoners in 1977, “sincere regret of the past and firm commitment for the future … the good resolutions that a person resolved deep in his heart, are known and revealed to the Supreme King of kings, blessed be He, who has given assurance that ‘nothing stands in the way of Teshuvah,’ and grants the requests accordingly … .”

Through a sincere contemplation of their past deeds and a firm resolve for the future, the Rebbe explained, it would also bring about “a change for the good in your present situation, by rousing compassion and amnesty in the hearts of those in authority who determine your status to speed up your freedom (in the plain sense), so that you can conduct your daily life at peace and inner freedom with yourselves and with society … .”

Join the Discussion