The U.S. Senate’s overwhelming 87-12 approval last week of the First Step Act, the most sweeping package of criminal justice reform in a generation, was lauded by those on the right and the left as a much-needed step in the right direction for the U.S. criminal justice system. The bill will expand early transfer to home confinement via participation in job training and re-entry programming designed to reduce recidivism; modify some mandatory sentencing laws; and ensure that the incarcerated stay more closely connected to their families by placing them within 500 miles of their homes, among other steps.

The bill went back to the House of Representatives on Thursday, where it passed by a massive 358-36 majority, and the next day was signed into law by President Donald Trump—who had been vocal in his support for the legislation—in the Oval Office.

The legislation’s path to fruition, however, was not as simple as it might appear. “For the bill’s supporters, Tuesday’s vote was the culmination of a five-year campaign on Capitol Hill that only months ago appeared to be out of reach ... ,” reported The New York Times. “Much of the same coalition that pushed the First Step Act had rallied around similar legislation, the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 ... .” That bill was shelved in the run-up to the 2016 elections when it wasn’t allowed on the Senate floor for a vote, dealing a blow to its longtime backers.

But who are these “bill’s supporters” the Times references—members of the “same coalition” that has been working at this for years?

The little-known answer is that the First Step Act was initiated, drafted and spearheaded by a small group of passionate Jewish community activists led by Moshe Margareten, a member of the Skverer Chassidic group. This activism was aided by the expertise and institutional knowledge of the Aleph Institute, the leading organization caring for the Jewish incarcerated and their families. The bill, which garnered national attention, will have a transformative impact on the American criminal justice system, affecting tens of thousands of inmates, both Jewish and non-Jewish.

It was at the urging of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—that Rabbi Sholom Lipskar, executive director of the Shul of Bal Harbour, Fla., founded the Aleph Institute in 1981. The Rebbe was a strong and early pioneer of criminal justice reform, seeing a fundamental flaw in incarceration disconnected from re-education and rehabilitation.

“If a person is being held in prison, the goal should not be punishment but rather to give him the chance to reflect on the undesirable actions for which he was incarcerated,” the Rebbe said in Yiddish in a 1976 talk. “He should be given the opportunity to learn, improve himself and prepare for his release when he will commence an honest, peaceful, new life, having used his days in prison toward this end.

“In order for this be a reality a prisoner must be allowed to maintain a sense that he is created in the image of God; he is a human being who can be a reflection of Godliness in this world. But when a prisoner is denied this sense and feels subjugated and controlled; never allowed to raise up his head, then the prison system not only fails at its purpose, it creates in him a greater criminal than there was before. One of the goals of the prison system is to help Jewish inmates and non-Jewish inmates ... to raise up their spirits and to encourage them, providing the sense, to the degree possible, that they are just as human as those that are free; just as human as the prison guards. In this way they can be empowered to improve themselves ... ”

Driven by the Rebbe’s vision, Margareten and the bipartisan Washington D.C.-based team he assembled proved tenacious enough to see the criminal justice reform bill over hurdle after hurdle, ultimately to last week’s historic passage and signing into law.

Particularly unique has been the bipartisan nature of support for the bill, which has illustrated that major change can happen when political sides agree to work together, despite steep political divisions. The original House bill, passed in May, was co-sponsored and championed by Rep. Doug Collins (R-Ga.) and Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), while the Senate bill was pushed by Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah); Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas); Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.); Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa); and Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.).

“This is a very moving night for me,” Booker told the Times following the bill’s Senate passage. “This is literally one of the reasons I came to the United States Senate, to get something like this done.”

‘The Family Collapsed’

As a child growing up in New York, Margareten recalls seeing a neighbor getting arrested. The imprisoned man had children Margareten’s age with whom he played, and as time passed he saw the deepening impact the father’s incarceration had on the family.

“I watched as the family collapsed,” says Margareten to Chabad.org. “From then on, I developed a strong feeling for the impacted family members. It became a passion.”

Such circumstances are increasingly prevalent. According to a report by Pew Charitable Trusts, 2.7 million children have a parent in prison and “two-thirds of these children’s parents were incarcerated for nonviolent offenses.” The Sentencing Project found that approximately 10 million children in the United States have experienced parental incarceration in their lives.

As a grown adult, Margareten began volunteering to visit people in prison. On one such trip to the Otisville Correctional Facility in New York in the late 2000s, he was in the waiting room when he witnessed a mother with her children showing their incarcerated father their Passover projects. One by one, the children recited “Mah Nishtanah”—the Four Questions traditionally said at the family seder—but in this case, instead they recited the Hebrew text in the sterile environs of a federal prison. Unable to contain herself, the mother burst out in tears.

“It was a horrible scene,” Margareten says on a short documentary telling the story of the First Step Act. “ ... At that time I figured, I’m going to go home, I will be sitting ... at a beautiful seder. Those kids, look what they’re going through. I felt, no more. I’m going to jump in; we have to do something.”

Margareten is careful to note that there is obviously a job for the criminal justice system to do, and those who commit crimes must pay their debt to society. The question was how to reduce the grave impact it has on the families of inmates, in some cases the greatest human victims (especially in many white-collar crimes), and also to be more effective about how the system goes about it. With the immensely high rate of recidivism for released prisoners, was it working as efficiently as it could? Were the heavy sentences handed down according to sentencing guidelines a fair way to deal with offenders? Could inmates earn their way back into society as opposed to wasting away behind bars?

In 2009, a prisoner Margareten had been visiting told him that if he was serious about wading into the murky waters of criminal justice reform, he needed to get in touch with Rabbi Zvi Boyarsky, the Los Angeles-based director of constitutional advocacy for the Aleph Institute.

A quiet, behind-the-scenes type of guy, Boyarsky is something of a legend within the criminal justice community. When, for example, Brooklyn businessman Jacob Ostreicher was caught up in a Bolivian extortion scheme connected with a rice-farming business he ran, and was arrested and imprisoned without charge, Boyarsky sprang into action. Through Hollywood connections he enlisted the help of actor Sean Penn, who eventually flew to Bolivia to investigate the case for himself. Penn has relationships with a number of South American leaders, including Bolivia’s Evo Morales, and managed to have him freed.

Among other things, Boyarsky also played a key role in the formation of Aleph’s 2016 Alternative Sentencing Summit at Georgetown University, which brought together 200 judges, prosecutors and lawyers, including politicians who later led the successful effort to pass the First Step Act, and was televised on C-SPAN.

So, back in 2009, Margareten got in touch with Boyarsky, telling him that he was determined to effect change in the criminal justice system.

“Moshe was incredibly passionate, and his dedication was beyond inspiring,” Boyarsky shares in the documentary. The concept Margareten was working on—educational and faith-based programs, participation in which would reduce prison time while also reducing recidivism—was “long overdue, and Moshe was committed to seeing it through, with G‑d’s help, recognizing the incredible impact this would have on thousands of families.”

Washington is a tricky place to do business, especially when trying to push an idea people have strongly held beliefs about. Still, it was impossible to know at the time that it would be almost 2019 when reform would actually be passed.

“This shows the impact even one person can have,” stresses Boyarsky. “Change can happen if you try.”

A Moral Imperative

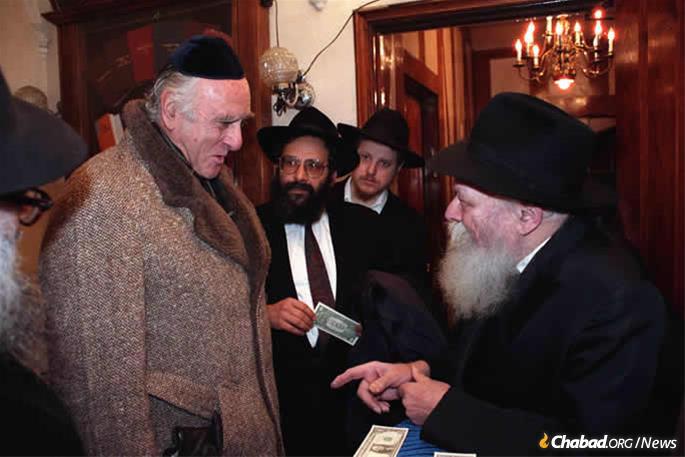

Rabbi Sholom Lipskar was at the Rebbe’s farbrengen gathering in Brooklyn, N.Y., in 1981 when he heard the Rebbe comment that while so much effort was being made to connect Jews from all walks of life to their Judaism, there were hundreds of Jews in prison, ready and waiting to study Torah, and yet no one was reaching them. The very next day, the Aleph Institute was born.

Those early years were spent working on basics: making sure Jewish prisoners could have access to kosher food and other essentials, sending rabbis and visitors to arrange Jewish holiday programming and the like (Aleph has a second duty, geared to assist Jews in the U.S. military and their families, and today is one of only two organizations that certify Jewish chaplains). Almost immediately, Aleph became known as a pioneer. It was among the first organizations to begin family support groups and was instrumental in the introduction of electronic monitoring into the prison system, allowing individuals to spend more time with their families even under such extreme circumstances.

As it grew and built a name for itself on the federal, state and local levels, Aleph and its philosophy continued to be guided by the Rebbe, who stressed the need to treat each and every incarcerated individual with the dignity and respect they deserve as human beings, and assist them in fulfilling their G‑d-given missions on earth.

“Similarly in regard to each individual, those who find themselves in a state of personal [exile]— there is no cause for discouragement and despondency, G‑d forbid,” the Rebbe wrote in a letter to Jewish prisoners in 1977. “On the contrary, one must find increasing strength in complete trust in the Creator and Master of the Universe that their personal deliverance from distress and confinement is on its speedy way. All the more so when this trust is expressed in a growing commitment to the fulfillment of G‑d’s Will in the daily life and conduct in accordance with His Torah and Mitzvos.”

One of the early backers of Aleph’s work was Judge Jack B. Weinstein, a former chief judge, and today, at age 97, an extremely active senior judge, on the U.S. District Court of the Eastern District of New York.

Lipskar and the team at the Aleph Institute, wrote Weinstein, “understand and force us to face the fact that each person deserves to be treated with respect as an individual personality and not as ... a faceless number ... .”

Lipskar recalls the time in 1985 when he got permission from the Bureau of Prisons to take a group of 20 screened prisoners from 12 federal facilities to take part in a mentorship program run outside of prison by Aleph. They all traveled to New York, and on Shabbat, Lipskar arranged for the men to join the Rebbe’s farbrengen at his synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn. It being a packed crowd, Lipskar pulled strings to have a table saved for his group so that they could be guaranteed seats together.

At 1:30, just before the farbrengen was set to start, the Rebbe sent a message to Lipskar via a secretary: The group should not sit together. People would see the prisoners come in together, recognize they did not look like Chassidim and ask them where they came from. This might cause the prisoners embarrassment; instead, the Rebbe said, they should be spread about the room.

On more than one occasion, including that day when the prisoners were in attendance, the Rebbe pointed out that imprisonment is not a punishment prescribed by the Torah, and is for the most part not found in the Jewish tradition. Every person has a mission and calling in this world—one they would be unable to fulfill if they were warehoused away; therefore, the Torah provides other methods of punishments, after which the convicted can go back to their lives and missions as human beings. However it evolved, Western countries had adopted prison as a model punishment, but, the Rebbe said, education and rehabilitation must remain at its core or else it would not respect the prisoner as an individual created by G‑d, thus not allowing him or her to return to their path.

It would also not be effective. This philosophy is borne out by the numbers. For example, a 2005-10 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that within five years of release, a staggering 76.6 percent of released prisoners are rearrested. Correctional facilities have been keeping the convicted off the streets, but were not being nearly effective enough in helping inmates change their lives around.

The prison system was far smaller back when Aleph started; according to the Bureau of Prisons, there were 26,313 people in the federal system in 1982. Today, there are 180,843 prisoners, down from a high of 219,298 in 2013. According to the latest Bureau of Justice Statistics report, a total of 2,172,800 people are incarcerated in America, not including people on probation or parole.

“The Rebbe was very much ahead of the curve,” says Lipskar, noting that the United States by now has 22 percent of the world’s prisoners, but only 4.4 percent of the total world population. “He saw what was happening, and he pressed that prisoners be treated with dignity, and that they be given educational opportunities so that they could use their time in the facilities for the better. Our focus on education in prison has been central because of this.”

It took years for others to get on board.

Mr. Margareten Goes to Washington

Aggressive legislation to combat urban crime, the drug war and to crack down on white-collar financial crimes came into effect in the 1980s, causing the U.S. prison population to balloon. While many of these efforts were pushed in good faith, there have been many unintended consequences. Mandatory minimum-sentencing rules set in place at the time meant that it was often not a judge who would be making the decision of how steep a sentence a convict would receive, but a math calculation. In an attempt to crackdown on crime, people stopped being considered as individuals. This has resulted in what’s by now been termed “mass incarceration.”

Therefore, in March of 2011, Margareten hired a lobbying group with experience in criminal justice reform, the Mitchell Firm, to begin working to convince legislators—with a focus on Republicans—of the pressing need for reform.

“For me, I saw it would be better for society if we were able to come up with a way that [inmates] could earn their way out of that prison bed early and get back home,” says Greg Mitchell of the Mitchell Firm on the documentary.

After an initial failure due to lack of time—a reform bill passed the Senate Judiciary Committee strictly along party lines and therefore could not conceivably advance—Mitchell brought Brett Tolman on board. Tolman, a former U.S. Attorney for Utah and a former chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee when it was chaired by Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), began working on drafting language for a new bill that could be introduced anew to legislators.

Nothing happened for almost a year, until Aug. 1, 2012, when Margareten saw that Tolman was scheduled to testify in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Yet the focus on outreach to Republicans saw some Democrats begin slipping away from supporting the bill that was forming, and so Margareten hired the Democrat-leaning Podesta Group. The first result of their efforts was the Federal Prison Reform Bill of 2013, which was ultimately not allowed onto the Senate floor by then-Senate Majority leader Harry Reid. The bill was focused on prison reform and did not include any sentencing reform, and so Democrats didn’t want to support it. It was back to the drawing board.

The problem was too little consensus on Capitol Hill on what such a greatly expanded criminal justice reform bill should look like. Margareten recalls those days as dark ones. He had been raising large sums of money to support his effort, but after such a failure, it began to dry out. Still, he persisted, and together with the Mitchell Firm, they chose to begin the process again.

This time the result was the greatly expanded Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015. The lobbying succeeded in getting bipartisan support for the sweeping bill, which flew through the committee 15-5, and was announced by Grassley as he stood flanked on one side by Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) and the other by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.).

In the end, however, with the 2016 presidential elections fast approaching, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell decided against allowing the bill to a floor vote.

When Trump was elected in November, it looked like the years of work Margareten and other had put in would have to end, or at least be put on hold. Trump ran as a law-and-order candidate, and chose Alabama Republican Jeff Sessions—who in the Senate had been a strong and vocal opponent of prison and sentencing reform—as his attorney general.

But it wasn’t over yet.

Last Hurdle, First Step

The key, this time, was the president’s son-in-law and senior advisor, Jared Kushner. Kushner’s father had been incarcerated for 14 months in a federal prison, and like almost anyone with such firsthand experience, he felt strongly for the cause.

Meanwhile, Mitchell was able to find new House sponsors for the newly drafted First Step (or The Formerly Incarcerated Reenter Society Transformed Safely Transitioning Every Person) Act in the form of Collins and Jeffries. In the Senate, Cornyn was back on board, joined by Lee, a former federal prosecutor who had also recognized deep problems with the system, particularly the mandatory minimum-sentencing.

Lee has on a number of occasions told the story of how as a prosecutor in Salt Lake City, he had seen a father of two young children caught selling three dime bags of marijuana to a law-enforcement informant in a 72-hour period. The young man—a first-time offender—had been carrying a weapon, thus the judge was forced, due to the mandatory minimum-sentencing equation, to give him a 55-year sentence.

“The average federal sentence for assault is just two years. The average murderer only gets 15 years,” wrote Lee in a Fox News article making his case for the First Step Act. “While acknowledging the obvious excessiveness of the sentence, the judge explained that the applicable federal statutes gave him no authority to impose a less-severe prison term, noting that ‘only Congress can fix this problem.’ ”

Still, at the heart of this bill is education, higher, vocational and faith-based, which has been proven in test cases such as the Texas model to greatly reduce recidivism.

“When prisoners don’t have anything to do in prison, they sit, watch television, play cards—in short, do nothing,” Margareten says. “Families are doing everything they can to see their loved ones come home, but when they finally do come home, they’re so often different people. They don’t get up to find a job, they’re not involved with their family, they’re moodless. They close down.”

Offering them an education—whether higher or a GED, job training and skills they can use on the outside or religious learning, or the ability to deal with substance abuse, while at the same time giving them the ability to shave off prison time—has been proven to keep former inmates outside of prison. The bill included other aspects highlighting the humanity of the individual, such as banning the shackling of jailed pregnant and postpartum women. It further makes it easier for inmates to submit compassionate-release requests in extenuating cases and allows the Bureau of Prisons to transfer elderly or terminally ill inmates to home confinement, where they can be surrounded by their families and receive better care than a prison can offer.

“The bill fits with Jewish values of the sanctity of human life, redemption, repentance and compassion,” notes Boyarsky. “But these are fundamentally American values as well. The First Step Act is a way for these values to be reflected in the law.”

Margareten and his allies worked with Kushner and his team at the White House, and Collins and Jeffries in Congress, and the House version of the bill successfully passed in May. The Senate bill passed last week, went back to the House, and then was signed by Trump on Friday, who said in a statement that “the First Step Act will make communities safer and save tremendous taxpayers dollars,” and it “brings much needed hope to many families ... .” A formal signing ceremony for the overhaul will take place in January.

While for Margareten what opened his eyes to the need to, as he says, “enhance the criminal justice system,” was seeing the toll it was taking on members of his own community, he believes passionately that the bill just passed is a positive step in the right direction for all inmates—and those around them—in America. He will be following up on implementation, and then, he hopes, on to more legislation and improvements in the justice system.

“Aside from all of the practical benefits of this bill, its most important impact is the awareness it has raised,” observes Lipskar. “The key is this new, total awareness that we need to be dealing with this issue in a humane fashion.”

While the Rebbe noted that prison is not a Jewish form of punishment, he did explain that its existence in the United States of America—a just and righteous country—meant that it had a valid purpose.

“The goal of incarceration ... is to return them to the good path, and to bring the incarcerated to a place where when they are released they will be able to open a ‘new page’ and to lead their lives in the way of justice and righteousness,” said the Rebbe at the 1985 farbrengen gathering that was attended by Lipskar’s group of Jewish prisoners. “Not only that, but they will be able to positively impact others by explaining ‘this happened to me,’ and this has been the result.”

“It’s called a ‘correctional facility,’ ” says Margareten, echoing the Rebbe. “It needs to correct people. We want to allow people the right of redemption, correcting themselves, so they can return to the productive lives they are meant to lead.”

Join the Discussion