If you’re familiar with bell bottoms, then you’ve crossed paths one way or the other with Eugene “Gene” Kule, the garment-industry visionary who introduced them to the American market and defined an era. Kule, an exuberant Brooklyn-born clothing businessman who passed away last month at the age of 84, was an industry innovator who in a half-century-long career became known as the “King of Pants.”

“He was the fast-fashion king of the time,” designer Tommy Hilfiger told Women’s Wear Daily. “He offered every new shape, style and fabric before anyone else. He was a pioneer and a great guy.”

Kule was the founder and owner of the trend-setting Happy Legs, and after selling it then founded Silk Club, which introduced washable silk to the market. “He was a fantastic salesman, a real show man,” his wife of 56 years, Arlene, tells Chabad.org.

Hundreds packed Riverside Memorial Chapel in New York City to bid farewell to Kule, including friends and colleagues he had made over the years. When it came time for a rabbi to speak, 31-year-old Chabad-Lubavitch Rabbi Shalom Cunin ascended the podium. Kule, however, wasn’t Cunin’s congregant in the traditional sense. The two met 18 years earlier, when as a young bar mitzvah boy, Cunin showed up at Kule’s office in Manhattan’s Garment District.

“I was a 13-year-old kid—the brim of my black hat came down over my nose,” remembers Cunin, today director of Chabad Westwood-Holmby in Los Angeles.

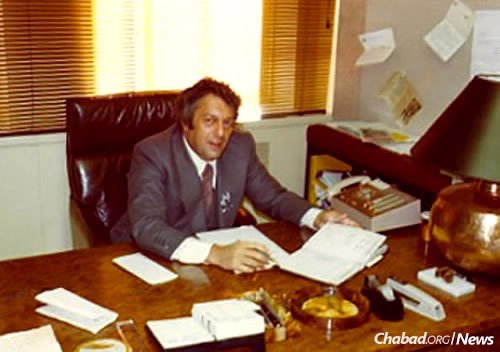

At the time, Cunin and his older brother would head to Manhattan from Brooklyn each Friday afternoon for mivtzoim, sharing words of Torah with Jewish businesspeople and shop owners, offering men the chance to put on tefillin and handing out Shabbat candles to women. Kule’s office at 1412 Broadway was on Cunin’s Friday route, but when the two yeshivah students first showed up at the office, a secretary turned them away. They persisted, and when the holiday of Purim came around insisted on hand-delivering their shalach manot basket directly to Kule. The secretary relented, leading them to a boardroom where Kule sat in the middle of a meeting.

“The Chabad boys are here!” Kule exclaimed when he saw them. With that, a relationship developed—one that would last nearly two decades, through good times and difficult ones.

“Rabbi Cunin, he had a special connection with my husband,” says Arlene. When her beloved husband passed away, Arlene called the yeshivah-bochur-turned-married-rabbi and asked him to serve as the rabbi at the memorial.

“I wanted someone who knew Gene,” she says. “I consider Rabbi Cunin to be family. Eighteen years . . . that’s a long time.”

Brownsville to Broadway

Gene Kule was born on Aug. 1, 1932, as Yochanan “Yudke” Kulichefsky in Brooklyn’s Brownsville, the son of Jewish immigrants from Russia, entering first grade with Yiddish as his primary language. Brownsville was a hardscrabble, overwhelmingly Jewish neighborhood, and like most others living there, the family was poor.

“They had nothing growing up,” confirms Arlene.

During World War II, one of Gene’s older brothers in the U.S. Army was captured in Europe and held as a prisoner of war. In light of her previous experience, following the breakout of the Korean War in 1950, Mrs. Kulichefsky prevailed on the Army to station her son Gene stateside, where he guarded top-secret sites housing atomic bombs.

Once out of the military, Gene—now following his brother in adopting the name Kule—got a job in the garment industry. His knack for sales was immediately noticeable, and when he decided to go out on his own, he offered his former bosses the opportunity to partner with him. One of them considered before declining. “That man regretted it for the rest of his life,” notes Arlene.

Kule gained a reputation for his honesty, a fireside-chat salesman who knew his customers’ birthdays and children’s names, and who never tried selling them anything they didn’t need. But he was also a showman, someone who brought Hollywood glamour to the shmatteh business. Later, when building a showroom, he designed it like a movie theater—with lights, turnstiles, popcorn machine and all.

“People waited in line to get to do business with him,” says Arlene. “He was a fantastic promoter.”

She remembers the time they were in London and on their day off at a flea market, her husband spotted a pair of pants with a belt in it. When they came back to New York, Kule created a belted pant. It became a “million-dollar seller.” Then there was the time he attached sunglasses to a pair of pants and sold them together. “They went crazy,” recalls Arlene. Or when he bought a huge amount of vintage vests, many of which had antique items such as railroad tickets tucked in their pockets.

“He put out a whole line and called it ‘Pop’s Closet,’ ” remembers Arlene, chuckling. “It was always one thing after another.”

It was Kule’s hard work and eye towards the future that allowed him to take flight of his humble roots and work his way up to an 8,000-square-foot apartment on Park Avenue, caring for his parents and family every step of the way. He saw something similar in the enterprising 13-year-old Cunin, who walked into his office with chutzpah, and in the Chabad movement as a whole.

‘Tefillin’ in Miami

Cunin visited the office on a weekly basis over the next decade, sharing a thought on the Torah portion or an upcoming holiday with both Kules—the couple worked together for 51 years, first traveling on the road together and later sharing a desk at their office. Kule took the conversations he was having with the growing yeshivah student seriously, sharing his own thoughts and advice in return. From time to time, he would put on tefillin, too.

“We’d always talk about it after he left. My husband liked what Chabad stood for,” says Arlene. “He felt it was more modern, more up-to-date. That it was about helping people. He would say, ‘We need to have people like this.’ ”

Kule and Cunin were truly kindred spirits. Kule had on occasion complained to Cunin that the Chanukah menorahs often set up in office buildings were unnoticeable alongside the far more prominent holiday trees. So prior to Chanukah in 2005, Cunin showed Kule his new idea: a massive, eight-foot blow-up menorah he wanted to attach to car roofs.

“He loved it!” recalls Cunin. “He told me to buy however many I wanted and that he would pay for them.”

That Chanukah, Cunin and a group of his fellow yeshivah students drove into Manhattan with their bright-colored, head-turning menorah secured to the roof, parking it in the heart of Times Square. Thousands stopped to take pictures and accept a tin menorah to take home for candle-lighting.

“People were flocking to us and asking for menorahs,” says Cunin. “The idea worked.”

Weeks turned into years. Cunin comforted the Kules when one of their daughters was in desperate need of a new kidney (miraculously receiving one). The Kules celebrated when Cunin got married, had children and moved to California to start his own center. A few years ago, Kule’s health took a turn for the worse, so the couple sold the business and relocated to Miami. When Cunin was scheduled to be there two years ago, he arranged to visit them at their waterside apartment.

“My husband wasn’t doing well by then. I could see Rabbi Cunin was kind of upset when he saw him; he had been a powerhouse, and now things were different,” says Arlene. “Rabbi Cunin felt our pain.”

Cunin stayed awhile, and although Kule hadn’t always agreed to put on tefillin, this time he did.

“He told me that he hadn’t been religious all of his life—that he had traveled the world and seen everything, but that the tefillin we would put on had meant so much to him,” recalls Cunin.

Kule also told Cunin that his grandson would be moving to California, and he hoped that the two would connect.

“I told my grandson that he’s going to California and I have two people there—one of them is Rabbi Cunin. He has been like family to him since,” says Arlene.

At 18, Reade Seiff is already the founder and CEO of a tech company on the West Coast. As a young child, he would often spend time at his grandfather’s office, watching how the family patriarch operated. “He always got his way,” says Seiff.

Since Seiff moved to California, he has been putting on tefillin with Cunin on a daily basis, saying that “it has been the greatest blessing.” Since his grandfather’s passing, he has also been reciting Kaddish.

Garment-Industry Royalty

Gene Kule was also a philanthropist who took the business of Judaism seriously. He saw the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—and Chabad as being on the vanguard of Jewish continuity.

“He would always say, ‘We need to keep the religion alive,’ ” says his wife.

Kule would ultimately remain garment-industry royalty. A veritable “who’s who” in the industry reacted to news of his passing, with household names like Michael Kors attending the memorial.

“Happy Legs was very aptly named,” Mickey Drexler, chairman and CEO of J. Crew Group told Women’s Wear Daily. “ . . . There aren’t many Gene Kules left today.”

Arlene Kule says that not long ago, she was introduced to someone in Miami she didn’t know, and a friend mentioned that Arlene had just lost her husband.

“What was his name?” the man asked.

“Gene Kule.”

The man’s face lit up instantly. “The King of Pants?”

In addition to his wife, Kule is survived by daughters Jodi, Farrah and Nikki; five grandchildren; and a brother, David Kule.

Also This Week:

New Mikvah in Nigeria: A Stunning ‘Spa for the Soul’

A spiritual experience for women in Western Africa, most of them Israeli

Also This Week:

The Rabbi of Idaho’s At-Risk Teens

Helping troubled boys ‘reinvest in their faith’

Also This Week:

On Greek Isle of Rhodes, a Long Road (and Short Flight) to Kosher Food

A popular tourist destination, especially for Israelis, gets a new Chabad center and restaurant

Join the Discussion