This is the third story in a series of articles on Jewish life in the former Soviet Union in the 25th year since the formal dissolution of the USSR on Dec. 26, 1991.

Twenty-five years ago this month, on Dec. 25, 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. A regime that had over the course of nearly 80 years uprooted freedom of expression and religious life—replacing it with fear and lies, enslaving and murdering three generations of its own people, and imprisoning the rest in mind, body and soul—finally heaved its last and collapsed. There to witness and partake in the historic events were three young Chabad-Lubavitch emissary couples who had arrived in the Soviet Union only a year before, chosen by the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—to be his first permanent shluchim sent to the Soviet Union: Rabbi Berel and Chanie Lazar in Moscow, Russia; Rabbi Shmuel and Chana Kaminezki in Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine; and Rabbi Moshe and Miriam Moskovitz in Kharkov, Ukraine.

Young and pioneering, naive and excited, at the time the rabbis and their wives were more focused on the work at hand than anything else. From the day they arrived, Jews in their respective cities—having been denied access to Jewish life for decades—were showing up in unheard-of numbers, studying Torah and learning about Jewish practice before promptly getting exit visas, and leaving the Soviet Union once and for all.

“Pietistic, emotional, rapturous—the typical descriptions of the special spirit-driven Hasidic strength—seem to contradict every plodding gray orthodoxy of Communism and explain the [movement’s] booming strength now in Moscow,” reported The New York Times on April 17, 1991, “if only as a fast-moving launching platform for thousands of Soviet Jews to Israel.”

But each wave of Soviet Jews filing out of synagogues and leaving was followed by yet another taking their place—men and women hungry for knowledge of their faith. For the emissaries, there was no end to their work in sight.

It was in 1989 that religious activity in the Soviet Union could first tentatively rise from the underground, but for battered Russian Jews accustomed to volatile political environments, the ingrained feeling of uncertainty remained. When the red hammer-and-sickle flag of the Bolshevik revolution was lowered for the last time at the end of 1991, it decisively meant that the evil empire was dead. Looking back at the events of 25 years ago, the Chabad emissaries remember their biggest concerns being over day-to-day difficulties.

“Certain things definitely became easier,” recalls Rabbi Berel Lazar, 27 at the time, and today the chief rabbi of Russia, “but economically, it became much worse. Right away, there was less food, there was less help, less money from abroad. In that sense, it became very difficult.”

The three couples first arrived in the Soviet Union in the summer of 1990. While Lazar had spent time there as an unmarried yeshivah student in the late 1980s, his wife, the Kaminezkis and the Moskowitzes had never laid eyes on the strange, broken land before. Today, Moscow, Dnepropetrovsk and Kharkov are home to burgeoning Jewish communities, constructed over time upon the ruins that greeted the arriving emissaries.

It’s a reality that nobody could have imagined.

‘The Year of Miracles’

Perestroika was underway by the time Berel Lazar first visited Moscow in 1987, and so the work that had until then been coordinated secretly by the Brooklyn-based Lishkas Ezras Achim—smuggling such items as Jewish books, matzah for Passover, and knives for the ritual slaughtering of kosher food or for the circumcision of Jewish males—cautiously came out into the open. It was also remarkably expensive. The Communist government had pegged the ruble’s official exchange rate artificially high, and although dollars could fetch more than 20 times the official rate on the black market, hotel and travel accommodations for the yeshivah students had to be purchased at the official rate. That translated into bills of nearly $20,000 for two young rabbis to spend six weeks in the country.

“During our travels, the locals would tell us: ‘It is our dream for a shaliach to be sent here,’” recalls Lazar. “In each city, they’d tell us that they badly needed teachers, but it was impossible for a foreigner to go there full-time. You couldn’t get such permissions.”

In 1989, a student-exchange program between the United States and the Soviet Union began, marking a turning point in practical relations. It was then that, at the urging of Jews in the Soviet Union, Chabad began considering the possibility of sending long-term emissaries to the USSR. Towards the end of 1990, the Rebbe—who since his own departure from the Soviet Union in 1927 had been deeply involved in materially and spiritually supporting the welfare of Soviet Jewry—began to speak of the miraculous changes taking place there. The Rebbe had himself even dubbed the acronym for the Jewish year, 5750, as the “Year of Miracles.”

Immediately after their wedding in May of 1989, Lazar and his wife wrote a letter to the Rebbe requesting to be sent as emissaries to the Soviet Union. The Rebbe responded that Lazar should first spend a year studying in a kollel, an advanced Torah institute for young married men. The couple spent a year in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., during which their eldest child, Chaya Mushka, was born (she passed away in 1997 at the age of 7; Keren Chaya Mushka, a free-loan society in Moscow, is named in her memory). On their first anniversary, the Lazars wrote another letter to the Rebbe asking for his blessing to be sent to the Soviet Union, at the time considered a provisional, one-year posting.

The Rebbe had been sending emissaries since his taking on the reigns of the Chabad movement in 1950; by 1990, their ranks were rapidly snowballing. But a new excitement surrounded the chance to go to the Soviet Union—the country that encompassed the birthplace of the Chabad movement itself. Lubavitchers felt a special connection to the place because it was where so many of them had their roots, and it was also Chabad activists who almost singularly kept alight the flame of traditional Jewish life through decades of Communist rule. A number of newlyweds were requesting to be sent to this exciting new posting, yet most received a negative reply from the Rebbe.

The Lazars got their answer minutes after giving their request in to the Rebbe’s office.

“This time, we got a positive answer and a blessing from the Rebbe, five or 10 minutes later,” remembers Lazar. “I gave in the note before Maariv [evening prayers] and got the reply right after.”

It was May of 1990 when the Lazars got their answer and began preparing to head to Moscow, the community that had requested them. Newly married Rabbi Shmuel and Chana Kaminezki had just previously received a blessing to head to the Rebbe’s childhood hometown of Dnepropetrovsk (today in Ukraine). The activity sparked the interest of another young couple living in Crown Heights: Rabbi Moshe and Miriam Moskovitz.

Caracas to Kharkov

Like the Lazars and Kaminezkis, the Moskovitzes were newly married and living in Crown Heights. Born in Caracas, Venezuela, Moshe Moskovitz was a Spanish-speaker; following his marriage to the Australian-born Miriam, the couple began looking into shlichus opportunities throughout Latin America. In their tiny apartment, Post-It notes with Spanish words were everywhere—in the kitchen, attached to chairs and doors, as Miriam tried to learn the language in preparation for what they thought was inevitable. The right position, however, had not come up. It was then that the couple learned that the Lazars had received a blessing to go to Moscow.

“We were looking for a place to go, and then all of a sudden, there was this whole new country filled with Jews to which no one had yet gone,” recalls Rabbi Moskovitz, today the chief rabbi of Kharkov, the second-largest city in Ukraine. “Beyond that, I can’t tell you why I decided to ask to go there.”

Yet even before asking for the Rebbe’s permission and blessing, the Moskovitzes had another significant hurdle: Moshe’s father was a Holocaust survivor from a town in the Carpathian Mountains, today in western Ukraine, who had lost the majority of his family at the hands of the Nazis and local collaborators. Permission from both sets of parents was a prerequisite to going, and so the young rabbi spent the next few days lobbying his parents. Seeing that their son and daughter-in-law were intent on going, the elder Moskovitzes gave their blessings, after which Moskovitz wrote a letter asking the Rebbe for a blessing to go to the Soviet Union.

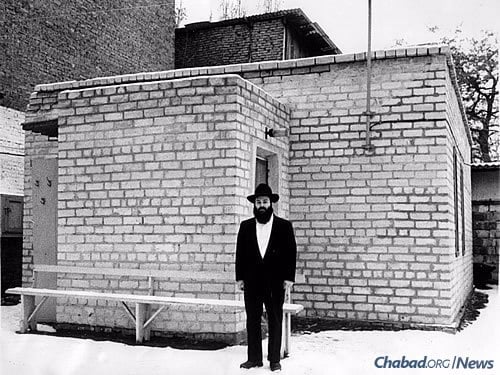

His letter asked for a blessing to go to Lvov (a small city also in Ukraine) or a similar city, to which the Rebbe responded to the affirmative, also within minutes. At the time, it was Ezras Achim coordinating the emissaries’ moves, and when the much-larger city of Kharkov began the process of returning the city’s massive Choral Synagogue to the Jewish community and a request for a rabbi came in, the Moskovitzes shifted accordingly.

“We did not know the difference between Minsk, Kiev, Kharkov or Lvov,” Moskovitz acknowledges with a laugh.

Down came the Spanish stickers in the couple’s apartment, and up went Russian ones.

In the next months, the soon-to-be emissaries stocked up on all manners of Western products, making special trips to Manhattan’s Lower East Side to purchase diapers, toilet paper, coffee, 220-volt small appliances and, above all else, coats. Having heard classic Chassidic stories of the brutal Russian winters, if the Chabad emissaries knew anything about their future homeland, it was that it was cold. The rest was guesswork.

“Everything I thought before we went was wrong,” says Kaminezki. “Nothing could prepare you for what was actually going on.”

Opening Up a Closed City

Dnepropetrovsk was the Kaminezkis’ destination. If Moscow was dark and dirty in 1990, it was Paris compared to the Dnepropetrovsk of the day. The city had been where the Rebbe’s father, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, had served as chief rabbi for 21 years until his arrest prior to Passover 1939. Following World War II, it became home to segments of the Soviet Union’s defense sector, with area plants building advanced rockets for missile systems and the USSR’s space program. As a result, all foreigners were banned from the Dnepropetrovsk region until mid-1988; even after that, the military continued to play a central role in the city’s governance.

Westerners were a rare, nearly nonexistent breed in the newly opened Dnepropetrovsk.

“The city’s one English-speaking guide,” reported the New York Times in April 1989, “has been about as busy as a salsa teacher at a cemetery, with only four Americans having wandered into this twilight zone . . . ”

A year later, on July 12, 1990, the Kaminezkis settled in that twilight zone. Of the 50 synagogues that had once graced Dnepropetrovsk, only one remained; the couples’ official welcome took place there. Two yeshivah students—Kasriel Shemtov, today executive director of the Mayanot Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, and Yisroel Spalter, today director of Chabad of Weston, Fla.—were on hand to greet the couple and help them settle into Room 513 of the Dnepr Hotel, where they ended up staying for months.

“We were followed by police every step. Nobody wanted to rent us an apartment. Many of the Jews were even afraid to approach us,” recalls Kaminezki. “We tried to hire a translator to help us, and he literally ran away.”

They had no food, and soon, no money either. They were also lonely. A phone call to the United States took three days to place and another three days to reschedule.

“My wife told me: ‘Until now, you were my husband. Now you have to be my friend, too,’ ” says Kaminezki.

But there were some successes. The couple immediately opened a Jewish afterschool program, which soon morphed into a full-fledged school that was named after the Rebbe’s father. When Kaminezki approached the city’s Soviet mayor about getting a building for the growing Jewish school, the mayor nearly threw him out, telling him to go back to America.

“In the shul, people told me that he’s an anti-Semite, and they knew I’d never get anything from him,” says the rabbi. “It took me a year to get back to him, but eventually, he became our biggest friend and directed the city to give us the enormous educational complex that we have today. It goes to show you, you can never label anyone.”

Among the primary factors fueling the Kaminezkis’ work was the Rebbe’s very obvious pleasure at the successful growth of Jewish life in the city his parents had given so much for—and his father had ultimately died for.

“My mother-in-law came back to New York after visiting us and gave a report in to the Rebbe,” says Kaminezki. “The Rebbe responded to her that the news was like ‘water on a parched soul.’ ”

The Place Marked ‘X’

Moscow was dark and overcast when the Moskovitzes arrived, a baby boy in tow, on the same plane as the Lazars. Making it through customs with their 10 suitcases, after a short and depressing visit to the creaking synagogue in the Marina Roscha neighborhood, they were promptly deposited on an overnight train to Kharkov. Paranoid about missing their stop and without the necessary language skills, the couple—who knew that in Cyrillic Kharkov began with the letter “X”—spent the entire night checking each stop for the familiar “X” of their new hometown.

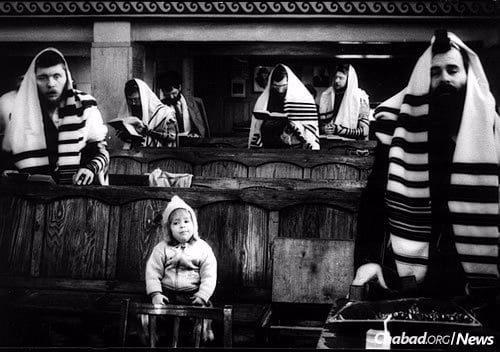

A rat-infested hotel in Kharkov would be their home for six months, Pepsi their breakfast, lavash bread their lunch and canned cholent-stew reheated on a burner their supper. Yet the excitement was irresistible. An incredible 1,000 Jews mobbed the synagogue for the new couple’s official welcome, many finding it impossible to believe that a rabbi could be so young.

“On Shabbat, my husband announced that we would be opening a Sunday school,” says Miriam Moskovitz. “I came in to the shul the next day with a few markers and some papers I had prepared. There were 150 children waiting for me.”

By Monday morning, 15 young men were enrolled full-time in Kharkov’s first yeshivah since before World War II. That Sukkot, thousands of Jews showed up for a Simchas Beis Hashoeva on Kharkov’s central plaza in front of its colossal statue of Lenin (the 66-foot-tall monument was torn down in 2014).

The newness of “freedom of religion” in the Soviet Union meant that Communist bureaucrats had no idea what they should and shouldn’t be giving permission for. Erring on the side of caution—in Kharkov, at least—the authorities gave the Chabad rabbi and his wife free reign.

“Any program that we thought of, anything, they said yes to,” says Miriam Moskovitz.

‘Seeing Them Off at the Station’

The same opening that had allowed for the Chabad rabbis to enter the Soviet Union was being utilized for emigration on a far larger scale by Soviet Jews. Locked in for decades, hundreds of thousands of the Soviet Union’s estimated 3 million Jews were running out the door.

“We came at the height of the exodus,” says Lazar. “I remember telling a reporter that I felt like I was standing in Central Station. Every day, people were coming in for a chuppah, bris, to learn something and prepare themselves for the West. We were preparing them to leave and then seeing them off at the station.”

Meeting new people each day proved difficult, and the hemorrhaging did not stop after the Soviet Union transitioned into Russia. Rampant anti-Semitism, no food and no money drove even more Jews towards Israel—any place being seen as a better alternative to Russia.

“We told people that we would be there until the last Jews had left—that we would turn the lights out,” says Lazar.

Numerous times the Rebbe had spoken of the underestimated population size of Soviet Jewry, a declaration borne out by what the emissaries were seeing. “For every Jew that left, we saw two show up,” says Kaminezki.

Lazar saw the same thing happening in Moscow.

Chabad, in what by then had become the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), began to shift its focus towards building local Jewish communities. A new chapter for post-Soviet Jewish life began around 1993, when diamond magnate and philanthropist Lev Leviev began his active investment in Chabad’s expansion in the former Soviet Union, establishing the Ohr Avner Foundation (named for his father) to open Jewish schools throughout the now-independent states. This move towards building local communities placed the emissaries on a collision path with those advocating for Russian aliyah to Israel, an argument Lazar rejected then and rejects now.

“They were saying we were fighting against aliyah by building schools and communities,” says the rabbi. “We answered that if we left, these people would be lost. We still see this today. Jews who have not had any connection to their Jewish roots in generations show up to activities to this day. We see how true the Rebbe’s words were.”

The USSR’s final dissolution did not initially change much. Kaminezki and Moskovitz now had to take flights through Kiev instead of Moscow, but the border between Russia and Ukraine was more of a formality than anything else. It’s only in the last three years that tensions between the two countries have made travel, trade and relations between the neighboring countries difficult, and at times, dangerous—circumstances that did not accompany the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

Today, Moscow itself has nearly 30 Chabad centers, while Dnepropetrovsk is home to the impressive Menorah Center, the largest Jewish center in the world. Kharkov’s domed synagogue, preschool, school, yeshivah and girls’ seminary produce young people dedicated to living Jewish lives. Back in 1998, the Federation of Jewish Communities of the CIS was formed to serve as an umbrella organization for Jewish communities throughout the former Soviet Union, the majority of which are served by Chabad emissaries. Now it boasts a presence in more than 250 cities throughout the former Soviet Union, 100 of them with permanent rabbis.

“Nobody really knows how many Jews are here,” Lazar told a New York Times reporter in 1995. “But there are enough for us to work our whole lives here.”

A quarter-century of momentous transformation later, that hasn’t changed.

Join the Discussion