Rabbi Moishe Mayir Vogel doesn’t mind substituting grape juice for wine at his Passover seders, where adults traditionally drink four cups.

Vogel hosts dry seders each year at the Northeast Regional Headquarters of the Aleph Institute in Pittsburgh, a nonprofit national organization based in Florida that works to help Jewish members of the military and Jews in prison, and their families. In this case, he helps people who have been released from prison or are part of some other government confinement, and not allowed to attend events where alcohol is served.

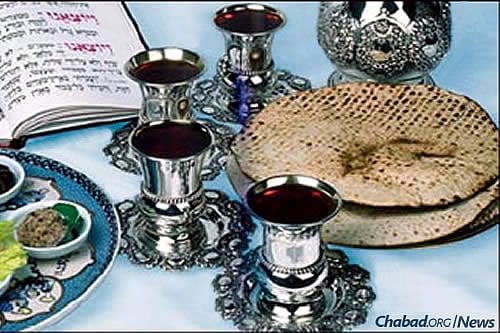

“It is no mitzvah to drink wine if wine is going to cause a problem,” says Vogel, who is executive director of the Chabad-affiliated organization and has been hosting the seders for five years now. Wine symbolizes the Jews’ freedom from Egyptian bondage, but at the Aleph seder, Vogel offers a variety of grape juices. And for attendees, “it is meaningful.”

“It is a very pleasant, very nice seder,” he states.

Vogel doesn’t feel like he is missing out on anything. And he is motivated by the desire to provide a seder for people who otherwise might not have anywhere to go.

In addition to helping Jews who are incarcerated—ensuring that they have access to religious services and kosher meals, as well as providing them with mentorship—Vogel and other staff assist people with re-entry through job-placement programs and support groups. About 350 people attend programs at the institute each week, according to Vogel.

They started hosting the seders because they saw that some of the people they serve “don’t have the possibility of making their own.” The events now attract people who have not been convicted of any crime, but attend because they are in recovery and do not feel comfortable at gatherings where people are drinking, explains Vogel. Family members of people who are incarcerated also often attend.

About 35 people attended the seder last year in Pittsburgh, and Vogel expects similar numbers this year.

‘Connect With Community’

The Aleph Institute is not the only place that hosts dry seders. Jordan Berkowitz attends one on the other side of the state at the Chabad-Lubavitch of Berks County in Reading, Pa.

Berkowitz, 29, has been sober for three years after abusing alcohol. He started celebrating Shabbat and other Jewish holidays at Chabad while going through treatment at a nearby center. He enjoys the seders in part because he gets to talk with people in various stages of recovery.

“I love it because it really keeps it green for me,” says Berkowitz, who owns an office-furniture business. “I get to see guys that are 10 days, 30 days, 90 days sober, dealing with those feelings about how tough it is and how grateful they are.”

The United States leads the world in the number of people incarcerated, with some 2.2 million people currently in prison, according to the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates for criminal-justice reform. But that number could decrease because there is bipartisan support for changing federal sentencing requirements.

Regardless of what happens on the national level, Vogel is focused on welcoming anyone who wishes to attend the Passover seder. “To see people celebrate who are otherwise isolated in the world with their own problems,” says the rabbi, “and to allow them to connect with the Jewish community and recognize the holiday is extremely gratifying.”

Start a Discussion