The second of two articles on Jewish life in war-torn eastern Ukraine.

The fighting was heavy when Maya and her family fled this summer from Lugansk, Ukraine. When she recently returned after three months in Moscow, her pantry was empty. Hungry neighbors had raided her home, taking any food products they could get their hands on. Canned goods, preserves, tea; all of it was gone. Nothing was spared, not even a few bunches of dill she had been drying to use for seasoning.

“The only thing left in her kitchen were two forks,” recalls Svetlana, a friend of Maya’s who works for the Lugansk Jewish community, and asked that she be identified by a pseudonym due to the volatile situation. “There isn’t marauding yet; they left her other valuables, but what happened to her is not uncommon.”

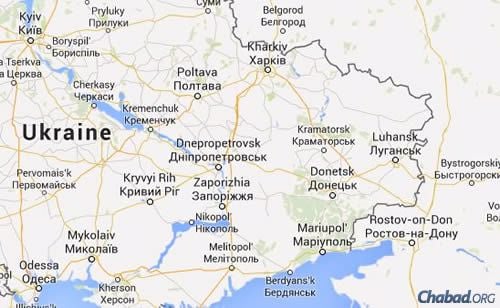

While intense fighting has continued unabated in the vicinity of Donetsk—sometimes spilling into the city itself—Lugansk has remained relatively quiet. The sounds of war can be heard in the distance, but the city itself has been untouched for months. Still, as it has become increasingly isolated from the rest of Ukraine, daily life has become more difficult.

“Right now, there are no trains going into the city,” continues Svetlana, who, in her communal position remains in regular contact with Rabbi Sholom Gopin, the city’s exiled rabbi and Chabad emissary. “They say they might restart them soon, but for now, you have to go to a nearby town and then take a bus in. We’ll see if that changes. All we’ve been hearing and seeing is less and less connection with Ukraine.”

Like other Jewish communities in Ukraine, Lugansk and its residents has been thrown a lifeline by the crucial support of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews, headed by Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein. From funding Chabad-run refugee camps during the most intense months of war to sending thousands of care packages throughout the battered Donbass region, the International Fellowship has by all accounts been a vital agent of help for the Jews of Ukraine. Likewise, the continued support of Ohr Avner and the Rohr Family Foundation has been essential to the survival of these communities.

As food and produce becomes scarcer, the regular care packages the organization has supplied—among other forms of assistance—through the local Chabad synagogues and centers have become crucial.

“Just a few months ago, it took us around two-and-a-half hours to get the packages from Severodonetsk [a city in Lugansk region under Ukrainian control] to Lugansk. Now it can take six or seven hours, going around the dangerous areas and driving through all the checkpoints,” explains Svetlana, adding that the aid is only let through with the help of a Ukrainian humanitarian nongovernmental organization. “There is heavy fighting around Stanytsia Luganska, which until recently was a big source of fresh vegetables for Lugansk; there was a milk-products factory there, too. Because of the fighting and the weather, produce from there hasn’t come into the city in weeks.”

The war has taken a heavy toll on the morale of the city’s population at large, including its Jewish community. Nevertheless, this year Jewish men, women and children gathered once again in their unheated synagogue to celebrate Chanukah, lighting a large menorah inside and on the building’s front steps, and receiving envelopes of financial aid packaged as traditional Chanukah gelt.

The warmth and joy that filled Lugansk’s synagogue—drawn from the candles and frequently refilled shots of vodka—was a fitting reminder of Chanukah’s message: the victory of light over darkness.

‘We All Miss Home’

Far away in Israel, when in past years he would have been lighting the menorah in Lugansk’s city center, Gopin and his wife, Chana, were celebrating with dozens of their closest community members in Ashdod.

Like the rest of his fellow emissaries in the Donbass, Gopin was forced to flee his home and community during the intense summer of fighting in Ukraine. With his family now temporarily living in Kfar Chabad, Israel, Gopin makes the three-and-half-hour flight back and forth to Ukraine often, visiting community members and ensuring that help gets through to those still in Lugansk.

As weeks of conflict have turned into months, Gopin has watched as some of the most vibrant members of his community have disembarked in Israel, knowing that each arrival, while positive for the family, is a blow to Lugansk’s close-knit Jewish community.

“Of course, I’m happy for them that they left; this is good for them and their families,” shares Gopin. “But for our community, this is still a very big hit. People are leaving who never planned on it. Many of them were the backbone of our community.”

After a night of catching up, dreidel-playing and menorah-lighting in Ashdod, the Gopin family—the couple has seven children—flew to Ukraine to spend Shabbat together with displaced Lugansk Jews, joining Donetsk’s Shabbaton in Kiev.

The Gopin family returned to Jerusalem for the last day of Chanukah, where the rabbi and his wife arranged another program for Lugansk’s Jews living near the capital. That night in Jerusalem, 35 recently transplanted Luganskers prayed together at the Western Wall, toured the tunnels that run alongside the wall underneath adjacent Arab homes and then sat down for a festive meal.

Unable to return home to Lugansk, the Gopins continue to work. Fifteen years ago, Chana Gopin founded The World of the Jewish Woman, a monthly Russian-language magazine. Throughout the ongoing situation in Ukraine and in whichever city she has found herself, she has continued to edit the magazine, ensuring every issue is published.

“It’s not easy,” says Gopin. “Our house, our car, everything we have … it’s all in Lugansk. Our children are in school in Kfar Chabad—and it’s a good school—but we all miss home. In the last five months, we’ve lived in 10 apartments. We desperately want to return to Lugansk in the next few months. Will that happen? I really don’t know.”

New Lifestyle Exceedingly Challenging

In the world of Chabad, shlichus is considered a permanent posting. Young couples wave goodbye to their families and set out on their assignments, filled with enthusiasm and a sense of mission. They build and work, buy homes, found schools, dig mikvahs and open synagogues. However difficult the years ahead may be, the vast majority remain for life, sure in their convictions that they have a job to accomplish in their chosen communities.

It was no different for the emissaries who settled in eastern Ukraine, and who, aside from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s local Chesed social-services branches, together made up the sole infrastructure of Jewish life in that part of the country. Although the emissaries and their families have received personal aid from Ohr Avner, the Rohr Family Foundation and the International Fellowship, the dramatic change in lifestyle—and the uncertainty that has followed—has been exceedingly challenging.

Until late June of 2014, Rabbi Eliyahu and Hadassa Kramer, and their 12 children, served the Jewish Community in Makeevka, a city of 350,000 people about 15 minutes away from Donetsk. A confluence of family celebrations brought the entire Kramer family to New York in June, but by the time they made plans to return to Makeevka, they were told the situation had become too dangerous.

“We weren’t even running away when we left,” Kramer says by phone from Jerusalem, where he is now staying with his family, and where his wife gave birth to their 13th child. “I spoke to Rabbi [Pinchas] Vishedski [co-director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Donetsk and the eastern city’s chief rabbi] and to other rabbis, and they told me not to go back.”

While Makeevka itself does not have a very sizeable Jewish community, Kramer also served isolated Jews living in surrounding towns. When he recently called a contact to find out if he should send him a Chanukah menorah and candles, the man declined, telling Kramer that he was afraid to leave his house to pick it up at the post office.

“This has not been easy,” says Kramer. “Traveling from one place to the other … my parents, my in-laws, and now in a small apartment in Jerusalem. You’re not here, and you’re not there. We are all waiting to get back to our shlichus, and we all hope we can do that. It’s been difficult, but G‑d helps us.”

Altogether 17 emissary families have been displaced by the war. They are couples who years ago relocated to faraway cities in order to help build the vision of the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—putting down roots, raising families and subsequently becoming vital catalysts for Ukraine’s Jewish rebirth. Today, these emissaries, rabbis and leaders of the Jewish communities of the Donbass find themselves in a state of transience, crammed into temporary apartments and hoping for the peaceful conclusion of a conflict with no end in sight.

Mariupol: The New Front Line

Most of the Donbass region is under the control of pro-Russian separatists, with little access to the outside world and where justice has become meted out in “people’s courts” by popular vote. In contrast, Mariupol—the 10th largest city in Ukraine—remains in Ukrainian hands; however, with war on its doorstep, the city has become the front line of the country’s war in the east. Just outside the boundaries of the port city, the Russian military has steadily been doing battle with Ukrainian defense forces, with rocket fire and shells often falling within the city limits. It’s been this way since September, and today, the threat of imminent warfare hangs heavy over Mariupol.

“People are scared. You hear shooting on a daily basis, see troop movements, injured soldiers—that’s what you see in Mariupol,” says Rabbi Mendel Cohen, who serves as the city’s rabbi and, together with his wife, Ester, co-directs Chabad in Mariupol. “My situation is better than everyone else’s because at least I can go back and forth into my city because it is still Ukraine, but the circumstances are extremely dangerous. I pray for safety each time I enter and exit the city. ”

Like the rest of his fellow emissaries, Cohen and his family are living in less-than-ideal circumstances in Israel, far from their own beds, clothes and toys for the children. They’re not home and don’t know when they will be able to return. “Emotionally, this has been a very difficult time for me and for my family,” he acknowledges.

While the presence of an actual government has sustained a semblance of normalcy in the seaside city, Mariupol remains a tinderbox waiting to explode. “On the eighth day of Chanukah, the day I went back to Israel, an important railway bridge into the city was blown up,” reports Cohen, adding that it remains unknown if it was the work of saboteurs or hooligans. “Now, I’m going back to Mariupol in about a week, but no trains can take you directly into the city.”

Mariupol’s Jewish community has continued to function despite the war, and even as stress—both economic and psychological—continues to bear down on all of the city’s residents, a minyan (the quorum of 10 Jewish men needed to pray publically) gathers daily; the kindergarten remains open; and an afterschool program takes place at the Jewish community center each day.

“Chanukah was really amazing,” says Cohen, who is in Mariupol for about one week each month. “People were so happy to see us; that we were there, celebrating together. We had events every evening of Chanukah—for the elderly, for young people and for families with children. Our young people also visited the homes of elderly and sick people to help them participate in Chanukah.”

Cohen says that for seven years, Mariupol has had a public menorah in its center, but this year he was advised not to assemble large crowds in open areas.

“It’s too dangerous, and I didn’t want to take that chance,” says Cohen. “It was painful when I drove by the place we usually do it. Hopefully, pulling back this year will lead to something even bigger next year.”

As he sat in a car on his way out of Mariupol, passing through multiple stringent Ukrainian military checkpoints, Cohen’s thoughts turned to the Jews of Mariupol. “We had such a nice Chanukah, old and young; it was beautiful. There was so much hope. How long can people live under the tremendous pressure they are experiencing now? Only G‑d knows how this will all end.”

The first of two articles on Jewish life in war-torn eastern Ukraine can be found here.

Join the Discussion