Canadian artist Leon (Chaim Leib) Zernitsky’s story begins in the ramshackle wooden homes in post-World War II Homel, a Belarussian city with a sizable Jewish population.

“I lived in the last remnants of the European shtetl,” recalls Zernitsky, who was born in 1949. “It was a very poor life. There was not enough food to go around, and many people did not have a place to live. Yet, even after the war, there were many Jewish people, and I would hear Yiddish spoken. They were shoemakers, wagon drivers and tailors—simple laborers.”

Even three full decades of Communist repression did not deter these simple folks from observing Judaism as they had for generations. “My bubbe (grandmother), Hende Friede Sirotin, was illiterate. Perhaps she knew a few key paragraphs of the siddur (prayerbook), but no more,” says Zernitsky. “Yet she kept a kosher home and prepared for the Sabbath as her mother had done before her. When they fled from the advancing Germans, spending the war years in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, they left everything behind. When they returned, all their possessions were gone, except for my grandfather’s Singer sewing machine, which he had hidden in a pit in yard.

Since bubbe no longer had her candlesticks, she would stick the Sabbath candles in a box full of sand, light them and say the prayers as before.”

Zernitsky’s grandparents raised goats, who supplied them with a steady source of fresh kosher dairy products. They also kept chickens. Occasionally, they would take a chicken to the shochet (ritual slaughterer)—an old man with a beard—and enjoy kosher meat. Since there was no kosher wine available, Zernitsky’s grandfather, Yosef Sirotin, would press grapes to make his own kiddush wine. Similarly, tucked away in the basement with heavy shutters protecting them from prying eyes, the neighborhood Jews would gather in one of the homes every year to bake matzahs before Passover.

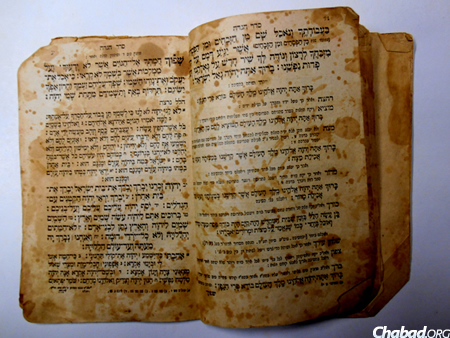

Zernitsky’s father, Aisik, was a wounded war veteran who painted houses together with a group of Jewish comrades. On Passover, the entire family would gather to celebrate secretly. “My bubbe was busy bringing food from the large wood-burning stove, and my zayde (grandfather) would sit and read the Haggadah text from his siddur—which I still have.”

Yosef made sure to take his grandson to the synagogue and teach him Jewish stories, mostly from the book of Genesis and the Midrash, the great collections of rabbinic lore.

The stories left a strong impression on the little boy. Full of memories and experiences, Zernitsky would not find expression for his Jewish upbringing until decades later. In the meantime, he focused on what would become a major force in his life: art.

‘Changes in Our Lives’

“When I went to school,” Zernitsky continued, “there was an art teacher who was a pro. Later on, I discovered he was Jewish. He would invite me and a friend for private lessons. I liked painting and wanted to be an artist. There was another student as well. He lives in Israel now.

“After I finished school, I was drafted into the Soviet army. There, I would make big posters showcasing whatever propaganda messages they wanted—the Communists did a lot of advertising.”

In 1975, Zernitsky was accepted into the exclusive Moscow State University of Printing Arts, which only accepted a cohort of 30 students a year, culled from across the Soviet bloc. He then went on to illustrate children’s books, an occupation he describes as “not painful,” since the Communists did not meddle with the content of the books, which typically featured fairy tales or classical poetry.

After marriage, the birth of a daughter, divorce, remarriage and the birth of another daughter, Zernitsky and his current wife Lena decided to immigrate to Canada in 1989. Like many other Soviet Jews at that time, the Zernitsky family’s path to freedom was through Ladispoli, Italy.

There, he met a young Russian-speaking Chabad rabbi, Hirsh Rabiski, who was tending to the spiritual and physical needs of thousands of Jewish people who were free to explore their heritage for the first time. During the eight months that the Zernitsky family remained in Italy, the two men began studying Torah regularly and developed a close relationship. It was a friendship that would continue to flourish when both Rabiski and Zernitsky relocated to Toronto, Canada.

“In Canada, I was preoccupied with making ends meet, working as a security guard, selling flowers and doing whatever I could to feed my family. My wife insisted that our daughter, Ilana, go to a Jewish school. Of course, we could not enroll her in a Jewish school and not live Jewishly at home. Slowly, we began to make changes in our lives.”

‘That Magical Place’

Over the years, Zernitsky—now using the Jewish name of his childhood, Chaim Leib—reclaimed the Jewish lifestyle of his grandparents and even completed the entire Talmud. He also gives a weekly Talmud class to 25 Russian-speaking Jews in Germany via Skype. “I especially liked the Aggadah, the rabbinic tales and homilies in the Talmud,” he said. “The stories are the poetry of Judaism, beautiful and warm.”

After re-establishing himself as an artist and illustrator—working for companies like Sony, McDonalds and Oxford University—Zernitsky felt it was time to begin painting Jewish themes, sharing his own childhood memories and subsequent experiences as a Jew. He describes the results as “Jewish parables in a visual form.”

A frequent reader of the Judaism website Chabad.org, where he goes to study and read, Zernitsky became aware of the “Art for the Soul” blog, which was created by New Jersey-based Chassidic artist Yitzchok Moully, as part of a broader project called the Creative Soul, which explores and celebrates Judaism through the arts. The year-old blog has featured more than 100 pieces of work from a kaleidoscope of Jewish artists from across the world. Zernitsky submitted some of his works, and they were soon featured prominently.

Just a few blocks away, Rabbi Tzvi Freeman, a senior editor and writer at Chabad.org, was working on a series of articles he had be planning for years, explaining how to approach the Aggadah and Midrash, the rabbinic tales that are often mistakenly taken at face value or discarded as fantasy. The ground-breaking work was the product of a close collaboration with Rabbi Yehuda Shurpin, a writer at Chabad.org and a member of its “Ask the Rabbi” team.

“Once we had researched all the research and written all the writing, we asked, ‘Where on earth are we going to get art that can complement all this?’ A page without art is dull. This is—at least to us—very exciting stuff.

“Then we saw Chaim Leib’s magical piece, ‘On the Road to the Rebbe’ It captures all the wonder and depth we hope to convey in this series.

“I spoke with Chaim Leib and discovered he lives around the corner from me. He’s a world-class artist, and I have probably met him many times and had no idea. He provided a whole pile of beautiful images that match the flavor of that first one. He also asked if he could create another work or two to go along with it. Of course, we were delighted.”

Both Zernitsky and Freeman point out that the art doesn’t illustrate the series in the strict sense of the word. “But,” explains Freeman, “we’re dealing with a topic that you have to feel with your heart as much as with your mind in order to get it.

“Chaim Leib’s work facilitates just that," says Freeman. " It reaches to that magical place in the heart where child and adult meet, and learn from one another. Which is very much what Midrash is all about.”

Join the Discussion