It’s become almost commonplace for hundreds of thousands of people to attend grand public Chanukah menorah lightings in metropolises and in front of statehouses dotting the American landscape. But the first such ceremony, in Philadelphia’s Old City in 1974, included less than a handful of Jews; they watched as a Soviet émigré stood in front of the Liberty Bell and lit a small menorah.

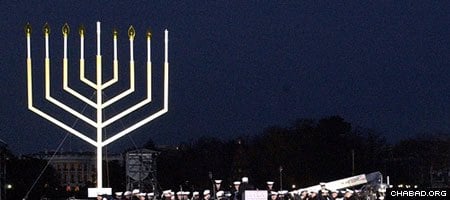

As he stood there celebrating religious freedom and the Chanukah message of light’s victory over darkness, Chabad-Lubavitch Rabbi Avraham Shemtov prayed from the depths of his soul that his small public act would fuel a groundswell of religious pride. Three years later, President Jimmy Carter would welcome the first National Menorah on the Ellipse in front of the White House; seven years later, President Ronald Reagan would endorse Shemtov’s hope in the form of a letter after the first presidential Chanukah party.

“May the light of the menorah always be a source of strength and inspiration to the Jewish people,” the president wrote Shemtov, the founding national director of American Friends of Lubavitch, “and to all mankind.”

The support of a succession of presidential administrations notwithstanding, the more-than three decades since the Chanukah light pierced the winter darkness in front of the nation’s birthplace have seen a series of court challenges lodged on Constitutional grounds. There’s the Supreme Court victory by attorneys working for the umbrella organization Agudas Chasidei Chabad, but there’s also a handful of cases that pop up time and again.

One year after Shemtov lit the menorah in Philadelphia, S. Francisco became the site of the first major public menorah lighting. Holocaust survivor and rock and roll impresario Bill Graham, acting on a suggestion from Chabad of Northern California founder Rabbi Chaim Drizin and KQED program director Zev Putterman, funded the creation of a 22-foot tall mahogany candelabra nicknamed “Mama Menorah” and the festival that went with it. Graham perished in a 1991 helicopter crash, but to this day, the Bill Graham Menorah Festival lives on under the direction of Rabbi Yossi Langer.

A line of American Chabad Houses, joined by state governors, followed with their own similar events, and in 1980, the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, issued a directive encouraging menorah lightings in public places. With strong grassroots support from local communities and the backing of other Jewish organizations, the pace of such events picked up and then, in 1987, the Rebbe formally launched a global Chanukah menorah campaign.

All over the United States, Chabad Houses sought out public spaces for the celebrations. But a handful of local lawsuits argued that the presence of a menorah on public property violated First Amendment guarantees on the separation of church and state.

The following year, the American Jewish Congress joined the debate, offering legal assistance to those challenging the celebrations. In 1989, countersuits had been filed in Des Moines, Iowa; Burlington, Vt.; Pittsburgh, Pa.; Los Angeles and Chicago. Later cases included those in Grand Rapids, Mich., White Plains, N.Y., Atlanta, Ga., Jersey City, N.J., and Indianapolis, Ind. Ultimately, the record reflected a mixture of wins and losses.

The battle-lines were drawn for the Supreme Court to weigh in.

In an extensive conversation from his Washington office, constitutional attorney Nathan Lewin, who argued the 1989 Pittsburgh case and appeal to the nation’s highest court, said that the case was emblematic for all future cases that challenged public menorahs as violations of the First Amendment’s establishment clause, which forbids government-establishment of religion.

He stressed that the existing case law contains many nuances, and that the definition of a permitted public space often hinges on whether or not the space is traditionally and regularly used for public expression.

Lewin argued before the Supreme Court that in Pittsburgh, the establishment clause didn’t apply because the menorah, as part of a display including another popular symbol of the holiday and a sign that celebrated liberty, didn’t represent a government endorsement of one religion over another. He won, but the following year, Mayor Sophie Masloff won a stay forbidding the menorah from being erected.

In response, Lewin used a strategy emphasizing that Pittsburgh’s religious-themed holiday decorations were displayed in a widely-used public area. Chabad should be allowed to express its views in a public forum, he argued. On a Friday, just hours before the holiday and the Jewish Sabbath begun, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Brennan vacated the stay.

“The Pittsburgh solicitor was furious,” recalled Lewin. “He wanted it to look like the town volunteered to put up the menorah instead of having been forced to go along with the Supreme Court, and they wanted to retain the right to reject on the grounds of separation of church and state.”

In the neighboring state of Ohio, a local Ku Klux Klan chapter threatened to erect a giant cross in Cincinnati’s Fountain Square if Chabad put up its menorah. Ultimately, the gambit failed.

“The local jurisdiction tried to close down the public forum for the season so that they wouldn’t have to deal with the Klan,” detailed Lewin. “Litigation was brought, and the district judge ruled for the menorah, but was overturned. We went to the Supreme Court and in the nick of time, again on a Friday afternoon, Justice John Paul Stevens – who voted against Pittsburgh – allowed Chabad to put up its menorah just before candle-lighting time.”

Lewin’s daughter, Alyza Lewin, noted that the Fountain Square case clarified what cities can and cannot do with their public spaces.

“The real issue is that cities fear the slippery slope,” she explained. “They worry they will have to put up crosses, crescents, and [other] decorations, even from the Klu Klux Klan.”

In truth, she surmised, “municipalities can demand permits and regulation, but they cannot close a public forum when it is open the rest of the year.”

All around the country, litigation eventually distilled what the Constitution guaranteed. In Atlanta, where opposition surfaced against a planned menorah lighting in the Capitol rotunda, the public-forum argument won the day. In Grand Rapids, Mich., the court ruled that another religion’s representation wasn’t necessary to make a menorah fit for public display. And in White Plains, N.Y., federal Judge Sonia Sotomayer – now a Supreme Court Justice – had what one pundit called her “menorah moment.”

In a case where she could have rejected the display of a public menorah based on a 1989 decision in Burlington, she instead upheld the right of a private party to deliver a religious message in a public forum.

Courts still handle questions over the Chanukah menorah, but by and large, said Nathan Lewin, such displays are a done deal.

“There’s still the possibility of discrimination [by a municipality], and there are problems and issues that continue to be raised,” he said. “There are cases every year, but they do not always result in litigation.”

Days before the holiday – it began Wednesday night – more-recent cases were still pending in Florida and North Carolina. The public library in Leander, Texas, decided not to display a menorah this year after a man threatened to sue over last year’s one. In nearby Austin, however, the holiday saw three major menorah lightings and Chanukah displays, one in front of the State Capitol.

In the nation’s capital, Rabbi Levi Shemtov, the Washington director of American Friends of Lubavitch who organized the lighting of the National Menorah Wednesday night, said the message of Chanukah is maximally revealed when it’s done publicly.

“At its core, the tradition of Chanukah, and specifically the lighting of the menorah, is a call for the amplification of light and tolerance,” he stated. “The National Menorah and thousands of similar Jewish celebrations around the world have taken this important message and placed it in a universal dimension.”

Join the Discussion