What Is a Jewish Wedding?

A traditional Jewish wedding (called a chatunah, חֲתֻנָּה) is a tapestry woven from many threads: biblical, historical, mystical, cultural and legal. Threads carried from one generation to the next, forming a chain of Jewish continuity which goes back more than 3,800 years. On the cosmic level, our sages teach that each marriage ceremony is a reenactment of the marriage between G‑d and the Jewish people that took place at Mount Sinai, and that the wedding day is a personal Yom Kippur—the holiest and most auspicious day of one's life.

But a marriage is also an intricate legal transaction, by which bride and groom enter a mutually binding commitment. The rituals and traditions of the Jewish wedding derive from both its legalistic particulars and its underlying spiritual themes—the body and soul of the Jewish wedding.

The Jewish wedding typically starts in midafternoon and ends late at night, but it can be longer or shorter. It is generally followed by seven days of celebration (sheva brachot, שֶׁבַע בְּרָכוֹת).

Kabbalat Panim—The Pre-Wedding Reception

The Jewish wedding traditionally begins with a special "kabbalat panim"—reception—in honor of the bride and groom. Our sages tell us that on their wedding day, the bridegroom is like a king and the bride is like a queen. Special powers are granted to them from On High; they are made sovereign over their own lives and over their surroundings. All their previous sins and failings are forgiven, and they are empowered to chart a new future for themselves and bestow blessing and grace to their loved ones and friends. It is to honor their special status that we hold a reception for them, as for visiting royalty.

Two separate receptions are held (usually in adjacent rooms) one for the bride and another for the groom. By tradition, the bride and groom refrain from seeing each other for a full week prior to their wedding, so as to increase their love and yearning for each other, and their subsequent joy in each other at their wedding. They will meet again only at the badeken (veiling ceremony) that follows the reception.

The bride sits on a distinctive, ornate throne-like chair. Her friends and family approach, wish Mazal Tov, and offer their heartfelt wishes and words of encouragement. At the groom's reception, songs are sung, and words of Torah are often delivered. Hors d'oeuvres, light refreshments, and l'chaims are served at both receptions.

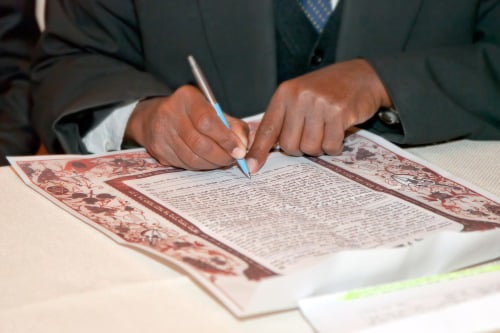

In many communities, this occasion is used to complete and sign two of the wedding documents: the tenai'm ("engagement" contract) and the ketubah (marriage contract). At the conclusion of the reading of the tena'im, the mothers of the bride and groom break a china or glass plate, to the joyous shouts of Mazal Tov!

Learn more: Kabbalat Panim—Pre-Chupah Reception

Badeken—Veiling the Bride

After the kabbalat panim receptions comes the badeken, the veiling ceremony. A procession headed by the groom goes to the bridal reception room, where the groom covers the bride's face with a veil.

The custom of covering the bride's face with a veil originated with our matriarch Rebecca, who covered her face when meeting her groom, Isaac.

The veil emphasizes that the groom is not solely interested in the bride's external beauty, which fades with time, but rather in her inner beauty which she will never lose. It also emphasizes the innate modesty that is a hallmark of the Jewish woman. The bride's face remains veiled for the duration of the chupah ceremony, affording her privacy at this holy time.

After the groom veils the bride, the parents of the bride and groom approach the bride and bless her. The groom's entourage then retreats from the room. The bride and groom proceed with their chupah preparations and everyone else continues to the site of the chupah, the marriage canopy.

Learn more: Badeken—Veiling

The Chupah—Marriage Canopy

The chupah is a canopy which sits atop four poles and is usually ornately decorated. The marriage ceremony takes place beneath this canopy which is open on all sides. This is a demonstration of the couple's commitment to establish a home which will always be open to guests, as was the tent of Abraham and Sarah.

Many have the custom for the chupah to be held beneath the open skies. This recalls G‑d's blessing to Abraham that his descendants be as numerous as the stars. Furthermore, a chupah held under the open heavens symbolizes the couple's resolve to establish a household which will be dominated by "heavenly" and spiritual ideals.

The chupah ceremony is traditionally characterized by an air of solemnity. Brides and grooms shedding copious tears is a common sight at traditional Jewish weddings. This is due to an acute awareness of the awe and magnitude of the moment.

It is customary in certain communities for the groom to wear a kittel, a long white frock, during the chupah. The pristine white kittel, traditionally worn on Yom Kippur, and the bride's white gown, are symbols of G‑d's atonement and perfect purity.

Indeed, the Shechinah, Divine Presence, graces the presence of every chupah ceremony. Joining also, are the deceased parents, grandparents and great-grandparents of the bride and groom, who descend from their heavenly abode to join the wedding celebration. The assembled audience is expected to demonstrate appropriate consideration for this holy occasion.

Learn more: The Chupah—Marriage Canopy

The Wedding Procession

Royalty are always escorted by an entourage; on the day when they are likened to king and queen, the bride and groom are accompanied to the chupah by escorts, a married couple, that serve as their personal "honor guards," usually the couple's married parents. Some have the custom for all the grandparents of the bride and groom to join the entourage as well.

The escorts lock elbows with the bride and groom while leading them to the chupah. All the escorts hold candles, symbolizing the fervent wish that the couple's life together be one of light and joy.

The groom is led to the chupah first, where he awaits the arrival of his bride. Customarily, the band plays a slow moving melody while the bride and groom walk down the aisle. In Ashkenazi communities, the bride circles the groom several times upon arriving at the chupah. With these circles the bride is creating an invisible wall around her husband; into which she will step—to the exclusion of all others.

Once the bride and groom are standing side-by-side under the chupah, the cantor welcomes them on behalf of all gathered by singing several Hebrew greeting hymns, which also includes a request for G‑d's blessings for the new couple.

After all this preliminary activity, we are ready to begin the actual marriage ceremony.

Learn more: The Procession

The Betrothal

According to Torah law, marriage is a two-step process. The first stage is called kiddushin, loosely translated as "betrothal," and the second step is known as nisu'in, the finalization of the nuptials. Both kiddushin and nisu'in are accomplished successively beneath the chupah: the kiddushin is effected when the groom gives the bride the wedding band, and the nisu'in through "chupah"—the husband uniting with the wife under one roof for the sake of marriage.

Kiddushin means "sanctification"—signifying the uniqueness of the Jewish marriage where G‑d Himself dwells in the home and the relationship is elevated to a new level of holiness.

The mitzvah of marriage is performed over a cup of wine. "Wine cheers man's heart," and there is no mitzvah which is more joyously celebrated than a wedding. The rabbi holds a cup of wine and recites the blessing over the wine and then the betrothal blessing, which thanks G‑d for sanctifying us with the mitzvah of betrothal before consummating marriage. The groom and bride are given to sip from the cup.

The groom then places the wedding band on the bride's finger. While putting the ring on her finger, the groom says: "With this ring, you are consecrated to me according to the law of Moses and Israel." The betrothal must be witnessed by kosher witnesses in order to be valid.

Learn more: The Betrothal

The Ketubah—Marriage Contract

After the groom places the ring on the bride's finger, the ketubah, marriage contract, is read aloud. The ketubah shows that marriage is more than a physical and spiritual union; it is a legal and moral commitment as well. The ketubah details the husband's principal obligations to his wife to provide her with food, clothing and affection, along with other contractual obligations.

The ketubah document is reminiscent of the wedding between G‑d and Israel when Moses took the Torah, the "Book of the Covenant," and read it to the Jews prior to the "chupah ceremony" at Mount Sinai. In the Torah, G‑d, the groom, undertakes to provide for all the physical and spiritual needs of His beloved bride. It is this precious "marriage contract" which has assured our survival through millennia which saw the disappearance of so many mighty nations and superpowers.

Reading the ketubah serves as a separation between the two phases of marriage—kiddushin and nisu'in.

After the ketubah is read, it is handed to the groom who gives it to the bride.

Learn more: The Ketubah—Marriage Contract

Finalizing the Nuptials

We now proceed with the final stage of the marriage ceremony, the nisu'in, which is effected by the chupah and the recitation of Sheva Brachot—the "Seven Benedictions."

It is customary to honor friends and relatives with the recitation of these blessings. The honorees approach and stand beneath the chupah, where they are given the cup of wine which they hold while reciting the blessing.

The first blessing is the blessing on wine, and the remaining six are marriage-themed blessings, which include special blessings for the newlywed couple. The bride and groom once again sip from the wine in the cup.

At this point the souls of the groom and the bride reunite to become one soul, as they were before they entered this world. Included in the Seven Benediction is the blessing to the bride and groom that they discover that same delight in one another that they knew in their pristine, primal state in the Garden of Eden.

A cup is then wrapped in a large cloth napkin, and placed beneath the foot of the groom. The groom stomps and shatters the glass. The shattering of the glass reminds us that even at the height of personal joy, we must, nevertheless, remember the destruction of Jerusalem, and yearn for our imminent return there. As the glass shatters, everyone traditionally shouts: "Mazal Tov!"

These sounds resound through the couple's married life. When your husband "breaks something" during your life together; when your wife "breaks something" in the years to follow, you too should shout, "Mazal Tov!" and say: "Thank you G‑d for giving me a real person in my life, not an angel; a mortal human being who is characterized by fluctuating moods, inconsistencies and flaws."

Learn more: Finalizing the Nuptials

Yichud Room

Immediately after the chupah, the bride and groom adjourn to the yichud (seclusion) room, where they spend a few minutes alone.

After all the public pomp and ceremony, it is time for the bride and groom to share some private moments; the purpose of the entire ceremony! Even while surrounded by a crowd clamoring to shower them with love and attention, they must take a few moments to be there for each other. This is an important lesson for marriage—the couple should never allow the hustle and bustle of life to completely engulf them; they must always find private time for each other.

Inside the room, the couple traditionally breaks their wedding day fast. It is also a time when the bride and groom customarily exchange gifts.

While in the yichud room, it is customary for the bride to bless the groom. She says: "May you merit to have a long life, and to unite with me in love from now until eternity. May I merit to dwell with you forever."

At Sephardic weddings, the newlywed couple customarily waits until after the wedding reception before entering the yichud room.

Learn more: Yichud Room

The Wedding Reception

Participating in a wedding feast and gladdening the hearts of the bride and groom on their special day is a great mitzvah. The Talmud relates that the greatest sages set aside their otherwise never-interrupted Torah study for the sake of entertaining a new couple with song and dance.

When the bride and groom emerge from the yichud room to join their guests, they are ceremoniously greeted with music, singing and dancing. The men with the groom, and the women with the bride, traditionally dance in separate circles; a mechitzah (divider) is placed between the men's and women's dancing circles. The singing and dancing, typically accompanied by juggling acts and other forms of amateur acrobatics and stunts performed in front of the bride and groom, continue throughout the reception.

A hallmark of the traditional Jewish wedding is that everyone is encouraged to participate in the dancing and merrymaking. Every Jew is seen as a part of the larger Jewish body, which includes every Jewish soul throughout the generations. A Jewish marriage, which creates a link between all the past generations and all the future generations, is therefore regarded as much more than a private milestone for the couple and their families; it is a historic and momentous event for the community at large.

After the first dance, the bride and groom take their seat at the head table alongside their parents, grandparents, the rabbi, and any other dignitaries in attendance. Traditionally, the groom recites the hamotzie blessing on an oversized challah which is then sliced and shared with the crowd.

Learn more: Reception

Grace after Meals

The wedding meal is followed by the Grace after Meals and the recitation of the Sheva Brachot, the same seven blessings recited beneath the chupah.

The seven blessings which draw Divine blessings for the duration of the couple's married life are recited over a cup of wine. There exists a deep mystical connection between wine and marriage.

Wine gladdens the heart. But in order to produce this heart-gladdening beverage, a grape must be crushed. Married life is full of crushing moments—the key is to together overcome those challenging occasions, which leads to new levels of love and happiness.

Before the Grace after Meals, two full cups of wine are prepared; one for the individual who leads the Grace, and the other for the Sheva Brachot blessings. After the grace is completed, six of the guests are invited to recite the first six blessings of the Sheva Brachot. Each of the honorees recites the blessing while sitting and holding the Sheva Brachot cup.

After the six blessings are recited, the person who led the Grace after Meals recites aloud the hagafen (wine) blessing and sips from his cup. The wine in the two cups are blended, and the groom sips from one cup and the bride from the other.

Learn more: Grace after Meals

A beautiful event has now reached its conclusion, and a solid foundation of joy and blessing has been laid for the eternal edifice that is the Jewish home.

Join the Discussion