Ever since we got married in 1999, my wife, Mushkie, has been telling me about her sister and brother-in-law who live in "exotic" Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine. She'd been there a few times as a single girl, and insisted that Dnepropetrovsk was a unique, remarkable and vibrant Jewish community; we simply had to visit there one day. Rabbi Shmuel and Chana Kaminezki, my brother- and sister-in-law, oversee Chabad operations in Dnepropetrovsk, and Shmuel also serves as the region's chief rabbi.

But "things" always have a way of coming up, and we never got our act together. That is until Passover of last year, 2008, when, together with our three children, we flew there for a three week visit.

Maybe the eight year delay was because that's about how long it took me to properly pronounce "Dnepropetrovsk" (Di-nep-roh-pet-rufsk). Once that tongue-twisting hurdle was surmounted, I felt ready to go... Having never before been to Europe, I was certainly looking forward to what promised to be a new and fascinating experience. And Dnepropetrovsk isn't just any European city—it is the city where the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson spent much of his childhood.

It was a few days before Passover, and our Aerosvit flight from JFK to our stopover in Kiev was packed. Surprisingly, a large number of religious Jews were on board the plane. No, Ukraine is not yet a vaunted Passover vacation spot. But it seems that a flight to Tel Aviv on this Ukrainian airline, with a stopover in Kiev, is a relatively cheap ticket.

A Different World

I would quickly find out that Ukraine is not America. In fact, I didn't even have to wait to arrive on Ukrainian soil to experience the difference in culture. The plane was delayed a few hours, Mushkie was on her cell phone talking to my sister, everyone was lounging around in the aisles, when suddenly the plane starts moving... No announcement. We're off!

As the plane approached its destination, I found myself glued to the window, mesmerized by the Ukrainian landscape; my emotions running wild. Jews lived in this land for many centuries, and have been persecuted throughout. Taxed, restricted from living in many areas, and oftentimes randomly butchered by the infamously anti-Semitic Ukrainian populace. The mountains, meadows and roads below me were soaked with the blood of millions of Jews—from the seventeenth century Chmelinizki pogroms to Babi Yar.

But, on the flip side, Ukraine possesses a rich and glorious Jewish past. The founder of the Chassidic movement, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, disseminated his novel teachings from the Ukrainian city of Mezhibuzh. I grew up regaled by my parents and teachers with stories about the mighty wonders performed by the Baal Shem Tov—stories that all occurred right here. The roads below me were once flooded with chassidim joyously making pilgrimage to their respective Rebbes...

My thoughts were interrupted as the plane made its landing. It was 12:45 p.m. local time and our connecting 45-minute flight to Dnepropetrovsk was to leave at 2:05. We stood at the gateway for fifteen minutes waiting for them to bring up the baby's stroller... We ran to immigration, waited on line, only to be told that we didn't fill out the papers properly, so back to the back of the line... We hurried to get our luggage (no, they don't automatically reroute to final destination), but no luggage carts available... We finally got a cart, ran to the domestic flights terminal... but our flight had left.

So we settled down to wait for the 5:00 flight. The lady at the ticket window – who thankfully understood a bit of English – explained to us that our e-tickets were no good; this terminal only accepted paper tickets. But she would try to make the necessary arrangements.

After around a half an hour, in to the terminal strolls a guy, walks straight over to us and introduces himself in Hebrew as Genya. He lives in Kiev, and was dispatched to the airport to take care of us (due to the delay of our previous flight, my brother-in-law figured that we wouldn't make our connection). Within two minutes we had tickets on the next flight. I later learned that one of the owners of this airline, Dnieproavia, was a personal friend and big supporter of Chabad in Dnepropetrovsk—and Genya was his top aide...

Weary but excited, we finally arrived at our destination. The driver who took us to my in-laws' home was driving like a maniac. I tried explaining to him that we were in no particular rush, but, looking out the window, it soon dawned on me that everyone was driving like that! It was something I'd get somewhat used to over the following weeks—that and the absence of lane markers, even on roads large enough for six lanes, and the nearly non-existence of traffic lights and stop signs, even at major intersections.

As soon as I arrived, I took a taxi to the synagogue for evening prayers. I entered the car and fastened my seatbelt. The driver was visibly offended. I tried to assure him that it was nothing personal and that I trusted his driving, but he didn't understand a word of English.

On the way to the synagogue, unable to communicate with the driver, I couldn't help but think: In Jewish literature, the human species is known as Midaber, "speakers." Why are we so identified with the faculty of speech? How about the human's intellectual superiority over all other genera?

But maybe our greatest asset is our ability to create communities, the fact that we don't each live in an isolated world of our own. What's all the intelligence worth if we cannot relate to another?

(Over the weeks I spent there I actually learned to read Russian; my nieces had a lot of fun teaching me a few new words each day... All of which I've managed to forget by now.)

Recent Jewish History of Dnepropetrovsk

A little interlude to describe a bit about the city:

Dnepropetrovsk is the third largest city in Ukraine, an important business and industrial center with a population of about a million, of which around 40,000 are Jews. Before the Soviet Revolution in 1917, the city's name was Yekaterinislav, named after the Russian Empress Yekaterina (Catherine). The Soviets, who renamed anything that was associated with Czarist rule, then changed the name to Dnepropetrovsk, after the rolling Dnieper River on whose shores the city sits. (Though many Czarist names were restored after the dissolution of the USSR, the Ukrainians have no love lost for Yekaterina, who ruthlessly oppressed them.)

In 1909, a young Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson moved to Yekaterinislav along with his family – including his seven-year-old son Menachem Mendel, later to become the Rebbe – after being appointed chief rabbi of the city. The Rebbe left the USSR in 1927, but Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and his wife, Rebbetzin Chana, remained on. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak continued to serve as the city's rabbi and defied the authorities by openly encouraging all to continue practicing Judaism.

In 1939, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was arrested and sent to exile in faraway Chile, and died in Kazakhstan in 1944. In the meantime the Nazis entered the city and exterminated the entire Jewish population. On one day alone, Simchat Torah of 1941, the Nazis rounded up and shot 11,000 Jews. The Rebbe's younger brother, Dovber, was also among those killed by the Nazis.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was a mystic and scholar of the highest order and a prolific writer. Unfortunately, most of his manuscripts remained in Dnepropetrovsk and were destroyed by the Nazis, too.

Though Jews moved back after the war, the city remained without a rabbi until 1990, when newly married, Israeli-born Shmuel Kaminezki and his wife, New Jersey native Chana, were dispatched by Chabad to serve as rabbi and emissaries to Dnepropetrovsk. Shmuel was at first hesitant to officially accept the rabbinic position – feeling inadequate to fill the shoes of the city's last rabbi, the holy Rabbi Levi Yitzchak – but the Rebbe instructed him to assume the position "mit dem shtempel" (complete with the official rabbinical insignia)...

Today, there are permanent Chabad-Lubavitch centers in 35 cities across Ukraine. Though other cities have larger Jewish population, Dnepropetrovsk was the first Ukrainian city to which Chabad sent an emissary. This because the Rebbe personally expressed interest in establishing a Chabad presence in the city of his youth. In fact, the Rebbe showed a keen interest in the Kaminezkis' operations and programs, issuing to Shmuel numerous directives and suggestions—and requested detailed reports of their activities. On several occasions the Rebbe referred to Dnepropetrovsk as "my city."

The beginnings were not easy. Ukraine was still part of the Soviet Union, and Shmuel knew that he was being followed wherever he went and that his home and phones were bugged. Many Jews still feared to be associated with anything related to religion. Couple that with the fact that there was no kosher food or supplies—they actually purchased a cow to provide kosher Chalav Yisrael milk for their young daughter, and Shmuel ritually slaughtered his own chickens.

Things could not be more different today. Under Shmuel's capable leadership, the city boasts a multitude of synagogues and multifarious Jewish religious and social organizations – many of which I visited and will soon describe – and a vibrant and growing Jewish community. The region even produces its own kosher chicken, meat and dairy products.

By the way, noticeably absent in this city is a significant middleclass population. Poverty is rampant, but I've also seen there more Rolls-Royces and Bentleys than I've seen anywhere else—driving alongside Soviet Era, Russian-made jalopies held together by duct tape. What's really incredible is not only the steep divide between the wealthy and the poor, but the fact that the two live side-by-side. It is very common here to walk down an unpaved broken-down road, a slum like you wouldn't find in the poorest city in the U.S., broken down shacks all around, and suddenly to see a stunning mansion—surrounded by gates and manned by 24 hour security.

Historic Synagogues

I arrived in the synagogue for evening services. This is the city's main synagogue, and it is bustling with activity. Tens of people are sitting around, some gathered around a table towards the sanctuary's rear, participating in a Torah class.

In the early 20th century, there were no less than 42 synagogues in this city. All but one were shut down by the Soviets. This particular synagogue I was now in, known as the Golden Rose Synagogue, is more than 150 years old, and was the largest in the city. Though Rabbi Levi Yitzchak didn't regularly pray in this synagogue, he would come here to officiate weddings and to deliver his homily on Shabbat Hagadol (the Shabbat before Passover, when rabbis would deliver an official pre-Passover sermon).

Across the street is a large building that served as a sewing factory, which, in the '20s, was government-owned and employed many Jewish workers—many of whom prayed in this synagogue. The government "convinced" the Jewish employees of the factory to declare that they no longer had a need for a synagogue, and it was converted into a theater. (As of when I was there, the sewing factory was still operational, though it was recently purchased by a Jew, and is slated to be converted into a shopping mall and a high-end housing complex.)

The synagogue was returned to the Jewish community in 1995. It reopened after five years of extensive renovations. It is truly a stunning edifice. Marble pillars and an imposing and exquisite interior architecture. Its acoustics are simply astounding. When evening services started, I looked around me to find the chazan (the leader of the services); I was shocked to see that he was on the other side of the room! In the Synagogue's lobby sits a one-of-a-kind "ATM machine," one that does not dispense cash—it only debits charitable donations.

The synagogue complex also hosts a kosher café, kosher grocery store, library, many of the community offices as well as the offices of the Joint (the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee).

When I was there, plans were being finalized for the construction of a hundred million dollar expansion of this community center. The seven story structure that will surround the synagogue will house a shopping mall – kosher cafés, coffee shops, Judaica stores and more – a Holocaust Memorial Museum, apartments for visitors, community offices, a large hall for weddings and other affairs, and more. The funding for this community center, projected to be the largest Jewish Community Center in the world, is being provided by world-renowned Dnepropetrovsker philanthropist Gennady Bogolubov, who also serves as the president of the Jewish Community of Dnepropetrovsk. Construction on this project has since commenced.

After evening services, my brother-in-law took me to see the Rebbe's father's synagogue—the synagogue where he prayed and officiated for many years, until the Soviets appropriated it and converted it into municipal offices. This building was also returned to the Jewish community and now serves as a dorm for the Jewish community's boys' orphanage. (The Soviets gutted the synagogue and renovated its interior; as such, its original synagogue structure no longer exists.) When we arrived, the building was also hosting a Passover camp—where I encountered some of the counselors who were my former students from back in the U.S. (The girls' orphanage, which I had a chance to visit on a later occasion, is a few blocks away.)

Outside this former synagogue, Shmuel pointed out to me an apartment building that contained one of the Rebbe's childhood homes. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and family relocated to different apartments several times during his tenure as rabbi; Shmuel surmises that this was due to pressure exerted by the local authorities upon the landlords to evict the family—part of their ruthless harassment of this holy family.

Here I am on the 11th of Nissan, the Rebbe's birthday, strolling the streets that the Rebbe walked nine decades ago...

A side note: Of the 41 synagogues the Soviets appropriated, only two have been returned—this one and the Golden Rose synagogue. The Rebbe instructed my brother-in-law not to pay money to buy back the other synagogues or any of the Rebbe's childhood homes. Once, while walking to the synagogue, Shmuel pointed out to me a building, that still sports a Star of David, that used to be a synagogue for Cantonists (Jews who, by decree of Czar Nicholas I, had been snatched from their families when they were young children for a 25-year term of military conscription).

The Oasis

The following morning, a more rested me went to the mikvah (ritual bath) before morning prayers. The mikvah is located two blocks away from the Golden Rose synagogue, behind a relatively diminutive synagogue—the only one that has remained open throughout the Soviet era (though the mikvah is a recent addition). Rabbi Levi Yitzchak prayed in this synagogue the last four years before he was arrested in 1939, after his other synagogue – the one I visited the previous night – was shut down.

The area all around this synagogue was recently built up into a massive high class shopping mall. (The following week, my family visited a bowling alley in this mall—the technology there way surpassed anything I've seen in the States.) But the synagogue was left intact, spared despite the fact that the whole surrounding area was razed to make way for the mall. It is a really interesting sight—an oasis surrounded and dwarfed on three sides by a shopping mall.

This synagogue currently houses an institute that trains locals to be scribes, a kollel (Torah academy for newly married men), some of the community offices, a Judaica store, and one of the many free soup kitchens operated by the Jewish Community.

The Visitor

The following day, Friday the 13th of Nissan, we were sitting in my in-laws' backyard burning the chametz (because the day before Passover was on Shabbat, the ceremonial burning of the chametz was performed a day earlier), when a visitor arrived. The city's security chief—the one in charge of the organization that was a direct successor of the KGB, and himself a former employee of that infamous organization.

On lounge chairs, he and Shmuel sat and discussed security measures being taken to protect the community during the upcoming holiday. It seems that Hezbollah had issued a threat against Jewish communities in the Diaspora.

It then hit me. On this exact date 69 years ago, the 13th of Nissan of 1939, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak's house was invaded by the KGB and he was arrested—never to return to Dnepropetrovsk. And today, the KGB visits again—this time to discuss, with the rabbi who succeeded Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, the measures they were taking to ensure the Jewish community's safety and religious freedom!

I pointed this out to Shmuel, who then repeated this information to the visitor, who responded with a broad smile. After an amicable conversation, the security chief left.

The next order of the day was baking matzah. With the destruction of the Holy Temple, the matzah we eat at the Seder serves double duty: it is the fulfillment of the biblical mitzvah to eat unleavened bread, and the afikoman matzah is in lieu of the Paschal Offering. Since the Paschal Offering was sacrificed after midday on Passover eve, it is considered a special mitzvah to have for the Seder matzah that was baked during this time period. (In the U.S., considering the large demand for, and the extremely limited supply of, this special matzah, it is very rare and expensive.)

Dnepropetrovsk has its own matzah bakery, under Shmuel's rabbinic supervision – which distributes matzah around the world – and they make a large batch of matzah on Passover eve. For the first time ever, I partook of this special matzah on the Seder night.

(A bit of history: From Dnepropetrovsk, the Rebbe's father supervised the production of Passover matzah for the entire USSR—and stubbornly resisted the regime's demands that he compromise his high kosher standards. Click here to see the Rebbe recounting this heroic saga.)

Passover Begins

Shabbat morning, early prayers to enable everyone to finish eating their chametz before the deadline: 10:19 a.m. And then a long relaxing day before the first Seder, scheduled for shortly after 8 p.m.—and children that need to be kept entertained. Luckily, Dnepropetrovsk has some perks. That morning on the way to services I noticed a house whose front yard was filled with chickens and turkeys. The kids had a blast—and to think that in the U.S. we pay for such entertainment...

Saturday evening, the first night of Passover, we all walked to the main synagogue for the Seder. The synagogue is a fifteen-minute brisk walk from my in-laws' house—straight downhill. Which is nice, on the way there. Walking back, however, with little children, at midnight...you get the picture. (For all our walks to the synagogue and back, we were accompanied by security guards—provided by the municipality for the city's chief rabbi. Talking about security, all of the Jewish institutions here are manned by guards around the clock.)

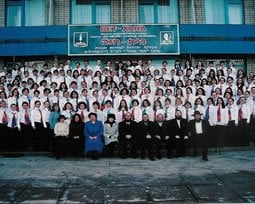

The public Seder in the Golden Rose synagogue was one of twelve public Seders operated by the Jewish community throughout the city. All the screwed-in pews were removed, and the sanctuary was filled with fifty tables that seated a little more than 400. While I didn't understand Shmuel's running commentary in Russian, I did enjoy the choir belting out traditional Seder songs, aided by the marvelous acoustics, as well as the delectable menu.

Next morning, I was astounded to find that my five-year-old son Berel and I were the only Kohanim (Priests) among the hundreds of congregants—and only one or two Levites were present. Joining me beneath my tallit and singing the Priestly Blessings has always been one of Berel's annual highlights. This time, his lone youthful voice carried beautifully throughout the sanctuary—and Berel immediately made the rounds, of both the men's and women's sections, to gather enthusiastic compliments and hearty Yasher Koachs!

I find it hard to believe that in fact there were no Kohanim or Levites in the room. Apparently, however, decades of Soviet persecution and persistent efforts to eradicate religion, during which time most Jews never set foot into a synagogue, has taken its toll in this area—with the religious elements of family trees completely forgotten.

But ultimately the Soviets failed miserably in their attempt to eradicate Jewish identity. Perhaps more than anything I was inspired by the many many senior citizens that I saw attending services. These are Jews who never got a lick of religious education, Jews who lived through systemic propaganda that made a mockery of G‑d and religion, Jews who till today have no clue how to pray, don't know how to don a tallit, and during the services sit when they're supposed to stand...

But they're Jews. They're back in the synagogue...

A Network of Goodness

During the days of Chol Hamoed, the "Intermediate Days" of Passover, I was taken to tour some of the city's Jewish institutions. A recurring question I would ask was, "How did you manage to obtain such an impressive building?" Without fail, the answer I received was always the same: "It was miracles; don't ask..."

My first stop was at the school; or, actually, a massive complex that houses three schools. The flagship school, Ohr Avner Levi Yitzchak Schneerson Day School, has an attendance of around 700 children—its high standard of education, in both religious and secular studies, attracts children from all backgrounds and levels of religious observance. Another 250 children are enrolled in another two schools – one for boys and one for girls – where the curriculum is even more intensive and religious studies are taught in Hebrew.

The Jewish community also operates two pre-schools. I was literally floored by the modern and spacious facilities. My wife, a pre-school teacher for many years, was in seventh heaven...

I was then taken to see the new women's mikvah that was under construction, nearly complete. (The mikvah has since opened.) Four stunning dressing rooms with imported furniture—each room with a unique design. And, Shmuel told me, they have already made arrangements for a female-only security staff.

My next stop was the old-age home—located on the other side of town, a half an hour drive away, across the Dnieper River. It's clear that no expense was spared to ensure that the city's elderly receive top notch treatment. From the magnificent waterfall in the lobby to the fully stocked personal fitness room to the entertainment center, the fully stocked library to the infirmary. The kitchen didn't disappoint either—the fresh hot pastries were delectable. The home has a fulltime rabbi, who administers to the religious needs of all the residents.

Our visit to the old-age home also gave me a clue as to the secret behind Shmuel and Chana's extraordinary success. They greeted every resident by name, with the men getting hearty handshakes and hugs from Shmuel, and the women from Chana. As Shmuel took me around the grounds, he made a verbal note to himself to speak to the groundskeeper about the grass, that had grown a bit tall... Their care for every individual and every detail was awe-inspiring.

(Later I found out that every Sunday, Shmuel vacates several hours from his busy schedule and sits in his office receiving anyone who wishes to see him. People come for all sorts of reasons: advice, spiritual guidance, or a few hryvnia – the Ukrainian currency, pronounced "grivven" – to make ends meet.)

I sat down for a chat with a female resident. She proudly informed me that she is part of the home's choir and dance troupe, she gives Yiddish classes to other residents, and she attends English classes (though I couldn't tell it...). When I asked her if she ever gets to go out, she proudly informed me that while others do go, she is so busy that she "doesn't have time to get out..."

It was at the old-age home that I learned about the Jewish community's Meals on Wheels program. Volunteers keep track of every elderly Jew in the city, and deliver food packages twice weekly. The volunteers write up regular reports on their "clients," and if it becomes apparent that a person can no longer live at home, he or she is transferred to the old-age home.

Royal Treatment

The next day, Shmuel informed me that he was sending me to see Beit Chana, the girl's seminary—also on the other side of town. To be honest, I was not so enthusiastic about making this trip—what could there possibly be of such interest in a seminary. It's simply a school for older teenage girls, no?

I couldn't have been more mistaken. Like everything else in Dnepropetrovsk, this is a seminary like no other. The director, Rabbi Meyer Stambler, and the principal, Rabbi Moshe Weber, told me a little about the history of this institute. Back in 1995, shortly after the USSR fell apart, poverty and inflation reached epidemic proportions. People were literally starving from hunger. Renowned philanthropist Lev Levayev decided to open a girl's high school/seminary where girls could come, at no charge, and be treated like queens—while also receiving a quality education. The seminary opened after a few months of planning, and girls flocked there from all parts of the former USSR.

Currently 180 girls are enrolled in this seminary, none of them from religious homes. The curriculum and equipment are state-of-the-art. A visit to the resort-like dorm building, located on a large tract of land on the edge of a forest, confirmed the high level of care provided to the girls. The girls, ranging in age from 16-22, leave with a government accredited teaching degree.

Moshe told me that as the first group of girls was getting set to graduate, the accreditation process had not yet been completed—and the prospects of having the government-sanctioned diplomas in time for the ceremony were quite dim. Nevertheless, the plans for the graduation ceremony proceeded on schedule. In a city where miracles were commonplace, they had complete faith that somehow someway the diplomas would be ready on time. And indeed they were.

Along with meeting the girls' educational and personal needs, the school's devoted staff attempts to gently coax these girls on the path to Jewish observance. With some they succeed more, with others less. This creates a special challenge, as the school encompasses girls on all different levels of observance—but none are pressured in any way. This was highlighted as I walked through the school's computer room, Meyer pointed out to me two girls sitting together in front of a screen; clearly they were close friends. "You see those two?" Meyer said. "One is engaged to a Chabad boy from Israel. The other is currently with a non-Jewish boyfriend."

A special moment was when Moshe and Meyer took me into the auditorium – where the girls practice drama, dance, and more – and showed me a large map of the former USSR hanging on one of the walls. Meyer flicked a switch, and mini light bulbs lit up on scores of points along the map. "These lights," Meyer explained, "are the cities and villages from where our girls have come." Some of the lights were in the farthest eastern stretches of the former USSR—thousands of miles from Dnepropetrovsk.

He then flicked another switch, and now the map virtually exploded with light bulbs. "Now these," Meyer continued, "are the cities where our alumni are currently serving in leadership posts, proudly representing Chabad-Lubavitch and disseminating Torah and chassidism."

I looked closely at the map (they were actually impressed that I could read the Russian names of the cities...). One of the cities there caught my attention. Izhevsk. My younger brother Schneur has spent Passover there several years ago, conducting a Seder for the small rabbi-less Jewish population... And now an alumna of Beit Chana is there...

I was then taken to another wing of the complex, devoted to special needs children. Children with autism and all other sorts of developmental disabilities come here to receive therapy and care.

The Ukrainian Federation

The offices of the seminary share space with the offices of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Ukraine, also headed by Meyer Stambler. The function of this organization is threefold: They supply the many Chabad representatives throughout Ukraine with religious supplies and needs, e.g. matzah for Passover, rabbinical students to assist with projects and activities, posters and signs for Lag b'Omer parades. They also coordinate with more than 150 small Jewish communities in Ukraine that have no permanent Chabad presence—providing them, too, with religious supplies such as prayer books, roving rabbis and more. Each of these cities has an appointed communal head who is in constant touch with the Federation. Lastly, using the power vested in them by the collective Ukrainian Jewish community, they exert political pressure when needed. For example, Meyer told me, the past year when nation-wide state school exams were scheduled for Rosh Hashanah, the Federation successfully lobbied to have the exams postponed.

"How many Jews are there in Ukraine?" I asked Meyer. "It's tough to know," he responded. He explained that throughout the Soviet era, many concealed their Jewish identity, and until this day do not advertise their nationality. He told me about a Chabad representative in a nearby city, a city previously thought to have a relatively small Jewish population. "But as soon as he built a beautiful synagogue," Meyer said, "they came out of the woodwork in droves. They confided in him that as long as there were beautiful churches but no synagogues, they were embarrassed of their religion. But now, they are proud to be identified as Jews!"

Dnepropetrovsk-esque Entertainment

Aside for the time spent touring institutions, in true Jewish tradition my family went on several fun outings during Chol Hamoed. We went to an amusement park (where no matter the size, anyone was allowed on any ride; the dogs running around – ignored by everyone else – gave me the scare of my life; and my daughter Chana got all sore from the insufficiently insulated bumper cars). We went to a zoo (a pathetically small collection of animals held in tiny barred cages. A few sad caged wolves and bears. Mushkie felt so bad for the animals that she fed them all our bananas, and then the peels). Bowling (as mentioned before, modern and beautiful). Ice skating (ditto), a boat ride down the Dnieper, and more.

Souls on Fire

The last days of Passover passed uneventfully. But the concluding moments of the holiday were clearly the highlight of my visit.

It was pouring rain as I headed to the main synagogue for the Seudah shel Moshiach, "Moshiach's Feast," that traditionally occupies the waning moments of Passover. Due to the inclement weather, I was expecting a meager crowd, but I was wrong again.

The sanctuary was filled to capacity. Hundreds of men sat around tables – set up in a T formation – filled with matzah, quality wine, fish and other assorted delicacies. (The women had their own inspiring Moshiach's Meal, led by my sister-in-law, in the adjoining library.) My brother-in-law sat at the center of the T, but the meal was led by a young bearded Russian chassid standing behind him, from a completely non-religious background. He first addressed the crowd in Russian, and then led the assembled in song.

As is customary on this holy occasion, one song associated with each of the Chabad Rebbes was sung, seven songs in all. As the singing of these beautiful melodies carried on, the emotions swelled, the holiness was palpable. And then, as soon as they concluded singing Hu Elokeinu, the Rebbe's song, the crowd spontaneously broke out singing Reb Levik's Niggun, the joyous Simchat Torah march sung by Rabbi Levi Yitzchak's hakafot. The ecstatic joy was electrifying; such pride in celebrating this special occasion in this special city. I could feel Rabbi Levi Yitzchak's presence in the room—as I'm sure all the gathered did too. Without a doubt he was there.

Next song was the famous "Who knows One?" sung in many communities after the Seder—but here it was sung in Russian, "Ech Ti Zimlak" (click here to watch as the Rebbe vigorously encourages the singing of this song). And the final refrain, sung again and again and again:

Odin, odin u nas Bog.

Shto na nebe, shto na zemle, odin u nas Bog.

Sluzhba nasha, nasha druzhba – nasha yevreiskaya…

We have only one, one G‑d

Both on heaven and on earth, we have only one G‑d

Our service, our friendship – is all a Jewish one!

I watch a man in his thirties with a long ponytail, his eyes are closed as he thumps the table with his fist and proudly sings at the top of his voice: "Odin, odin u nas Bog!"

A Jewish soul ablaze, one of many seated in this room

Indeed, indeed, this is the Rebbe's city.

I feel privileged to have visited.

Join the Discussion