Beyond Rodin’s The Thinker and Jacques Lipchitz’ enormous sculpture gracing the entrance of Columbia University’s Jerome Greene Hall, students in the prestigious School of International and Public Affairs are sitting silently across from each other, fixing gazes into the eyes sitting opposite.

Some burst out laughing, others fiddle uncomfortably, while others shift their glance to the features on the faces of other students. The exercise, presided over by noted professor Thomas D. Zweifel, provides a unique lesson on leadership and interpersonal relationships by focusing on how to pay attention to others.

Leadership in International and Public Affairs, a weekly course in Room 901 for two hours in the afternoon, is not like any other class. Many of the students hold foreign citizenships and, while enlisted at Columbia, are connected to any of a number of international institutions in New York, including the United Nations. Zweifel, a 46-year-old French-born, Swiss-bred expert in global management, tells his class that leadership means far more than simply giving orders. Self-realization is paramount.

“We need be to be aware of who we are,” Zweifel tells the students, who come from such countries as Georgia, Germany and Japan. “That is what makes us winners or losers.”

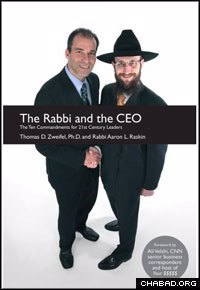

Speaking the language of Chassidic luminaries, Zweifel – co-author of the just-released The Rabbi and the CEO: The Ten Commandments for 21st Century Leaders – continually refers to the refining of one’s self, the ability to change one’s acquired nature and the egoistic tendencies possessed by all human beings. The approach has a resonance with students, who during class openly discuss their personal ambitions, their life goals and weaknesses.

Zweifel reveals his belief that every individual is a leader, whether at home, in the office or in one’s community. Students have caught on to the message.

“Its all about leadership qualities and interactions,” says Abdul Hye, who works for the United Nations and enrolled in the course to learn leadership responsibilities. “He is very knowledgeable on global leadership, and I have learned how to work at the grassroots level.”

Learning Leadership

Born into a relatively secular household in Paris and raised in Basel, Zweifel received the Jewish middle name of David only after his grandmother requested it. The experiences of World War II had instilled in his parents an intense fear of anti-Semitism, which in turn led them to deemphasize their son’s religious identity.

“I barely knew I was Jewish,” says Zweifel, who today sprinkles his conversation with such Hebrew words and Judaic concepts as tzedakah, ein sof, Mitzrayim and shofar.

From his Brooklyn Heights studio apartment, where he’s surrounded by vintage works of art, he elaborates on his family background. His middle name is in memory of Rabbi David Strauss, a one-time chief rabbi of Zurich and father of Zweifel’s grandmother. In Basel, it was the grandmother’s annual Chanukah party that provided the young Zweifel with his only Jewish experiences.

Pointing at a case filled with Judaica that belonged to his grandmother, Zweifel emphasizes that despite a youth filled with Jewish ignorance, he was nevertheless proud of his identity.

“I was proud that I was Jewish,” he says. “I had always admired the Jewish leaders and innovators. Einstein was Jewish and Freud was Jewish.”

At 17, Zweifel became an actor, finding work at the Stadttheater Basel and later co-founding the Wertheater Basel. As a thespian, he began developing the leadership qualities that would earn him international acclaim. The key in leading, he says, is to recognize not only your own traits but those of the people around you.

In acting, “you learn how it feels to be a baker, or a thief,” he explains. “You learn to empathize with a character.”

In 1984, he joined the Hunger Project, an international non-governmental organization accredited by the United Nations. As its director of global operations he managed a team of employees in 22 countries. But despite his title, he lacked any control over whom the project employed and had little power to ensure their effectiveness on the ground. The experience honed his ability to cajole and convince, rather than force.

“I just wanted to tell people, ‘You’re fired,’ ” he says, but “someone had to make sure that they sang from the same song sheet.”

The mission took him all over the world in an effort to coach people on the front lines of hunger relief. Only after he left the project in 1996 did he realize that he had produced an art of leadership, and he set out to write his first book: Democratic Deficit? Institutions and Regulation in the European Union, Switzerland and the United States.

(To date, he’s written five books. His Culture Clash is used by the U.S. military in training its personnel for combat in foreign lands.)

One year later, he founded the Swiss Consulting Group, a leadership consulting and development company with 20 associates in 12 countries.

“It’s all about the human capital, the human spirit,” he says of his firm’s approach.

Zweifel himself continues to travel around the world as a leadership consultant to Fortune 500 companies.

In 2000, Zweifel, who speaks five languages, began his course at Columbia. Little did he know that a chance encounter on the Brooklyn Heights Promenade with views of the Lower Manhattan shoreline changed his life.

One day after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, Zweifel was sitting on the promenade holding a lit candle, joining countless other residents and workers in a contemplative, collective stare across the East River at the smoke rising from the rubble of the World Trade Center.

“Are you Jewish?” asked a bearded rabbi in a black fedora holding jars of honey, a ram’s horn and a small bag.

Zweifel answered that he was, and Rabbi Ari Raskin, director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Brooklyn Heights, asked him if he wanted to put on tefillin. Zweifel didn’t even know at the time what the black boxes worn by Jewish men during prayer were.

But ever the fearless figure – Zweifel was once described by The Wall Street Journal as the “fastest CEO” after finishing the New York City Marathon in less than three hours – stood up in front of the tableau of humanity there that day and donned tefillin.

“It was a slightly unnerving experience,” he admits. “What if they all found out I was Jewish? They might never do business with me again. But I decided in that moment, if they [did that], it’s their problem.

“It was like me coming out of myself.”

After the encounter, Zweifel started attending Shabbat services at Raskin’s congregation, B’nai Avraham. Torah classes soon followed, as well as one-on-one sessions with Raskin and other rabbis.

“Every commandment adds another dimension of depth to my life,” says Zweifel.

Jewish Leadership for All

In the B’nai Avraham synagogue’s study hall – an elegantly-appointed room draped with gold curtains and burgundy tassels that sits at the rear of a Brooklyn Heights brownstone – Zweifel has his nose buried in a thick volume as he discusses Chasidic thought with Raskin. It’s a few moments before the arrival of Zweifel’s study partner and the professor is going over the text – a section from a collection of discourses delivered by the first Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi – with the rabbi.

Zweifel is here to sharpen his Hebrew reading skills. Although he learned to speak the language 10 years ago, he has difficult pronouncing the written word.

Finally, his study partner, Rabbi Motti Seligson, arrives and Zweifel takes up another volume, a prayer book. While accomplished leaders could be forgiven for a hesitancy to learn from those younger and less experienced in life, Zweifel enthusiastically refers to Seligson – more than 20 years his junior – as “my coach.”

“My dream is that I can read the Torah and lead the congregation,” he says, sipping on tea before chanting the next paragraph of the prayer book.

The time spent at B’nai Avraham has clearly affected him in more ways than one. The Rabbi and the CEO, which looks at the nexus between Judaism and leadership, was co-written with Raskin. His studies have also provoked a greater understanding of uniquely Jewish leadership, and the philosophy behind such leaders as Moses. Many of the concepts he teaches at Columbia are “greatly influenced by Jewish concepts,” he says.

Turning to the subject of Moses, Zweifel talks about the Exodus from Egypt as a metaphor for modern life.

“First you have to leave your own Mitzrayim,” he explains, using the Hebrew word for Egypt and referencing the Chasidic concept of breaking out of one’s own boundaries.

You must determine what your boundaries are, says Zweifel, and only then, “can you create a strategy and vision of the future.”

A man who now peppers his speech with allusions to Chasidic tales, Zweifel has a favorite teaching that is ascribed to Rabbi Zusha of Anipoli, a disciple of Rabbi Dovber, the Maggid of Mezeritch. Rabbi Zusha is quoted as saying: “In the world to come, I will not be asked why I was not Moses. I will be asked why was I not Zusha.”

“Leadership has a lot of doing to come to your full potential,” states Zweifel. You shouldn’t envy others’ abilities, but should make the best use out of your own capabilities.

“The basic humility of a Rashi,” says Zweifel of the famous 13th-century sage and Torah commentator, “is that several times, he says, ‘I do not know.’ ”

In a discussion on 20th-century examples of failed leadership, Zweifel blames leaders’ hesitancy to display humility and accept Divine Providence.

“The Germans lacked that humility,” the professor says of the World War II era, before going on to quote from a letter penned by the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. “What can guarantee that people will behave in a righteous and just manner, if not for the belief in a Greater Power?”

“Jewish philosophy and Chasidic thought,” concludes Zweifel, “has integrated everything that I have done in my life. It has created a being and purpose of who I am.”

Start a Discussion