"A long time ago the Jews lived in California where the king was a very nice guy named Kong."

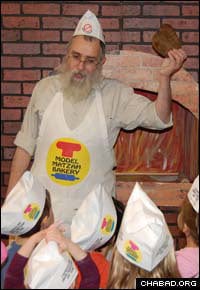

So says Rabbi Nechemia Vogel to about two dozen laughing first graders from the Sinai Hebrew School in Rochester, N.Y. They're assembled at the Jewish Community Center for a session of Chabad-Lubavitch of Rochester's model matzah bakery, and quickly correct the rabbi's "errors." Lasting about 60 to 90 minutes, the program is presented numerous times during the course of a week to ten days, with some sessions reserved for groups, and others open to families and "drop-ins."

Vogel, the co-director of the Chabad House since 1981, has been rolling the dough for 26 years now, traveling with an oven, wheat kernels and everything in-between that is needed for the mock bakery. When Vogel began the program – it is now a staple of Chabad-Lubavitch centers across the globe – he had a head full of black hair and was brimming with energy. Today, Vogel, who has four other Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries to assist him, still has the energy, but sports a white beard. He gladly rolls up his sleeves to teach the children about matzah and how it is made.

Vogel begins with a brief recap of the story of Passover, liberally sprinkled with mistakes for the children to discover and fix. Then he emphasizes the importance of speed in making matzah, explaining that the dough begins to rise after 18 minutes, turning it into chametz, or leavened food that is prohibited to eat on Passover.

"That's why matzah is the world's first fast food," he says, concluding with a poem:

If you're slow with the dough,

The dough has to go.

Speed is what you need.

He describes how wheat is grown and invites the kids to look at the grains of wheat spread across the table. They take turns putting grains into the grinder, cranking the handle and watching as a yellow-white powder spills out.

"That's flour," says Vogel, who then moves to mixing area where he chooses two young assistants to help him pour water and flour into a bowl.

"Does the matzah have sugar?" Vogel quizzes the kids.

"No," they respond.

"Does it have chocolate chips?"

"No chocolate chips," they respond, many laughing by now.

"It's only flour and water and nothing else. No sugar, no MSG, nothing else," he says.

"In a real matzah bakery," he explains, "we build special huts for the flour and water, so the flour doesn't get wet accidentally, causing it to rise after 18 minutes."

After kneading the dough for a while, he invites the group to move to two long tables full of easy-to-clean rolling pins and sandpaper. Vogel demonstrates how to clean the pins with the paper to remove any unbaked dough. Standing at the head table, he then passes around a ball of the dough to each child.

The rabbi encourages the children to squish the dough in their hands to soften it up, and then use the rolling pin to roll it into a thin circle.

"Square matzah is easier to pack into boxes," he offers. "But we're going to make round matzah, similar to the way the Jewish people made it when they left Egypt."

A Dozen Little Hands

"If air gets inside the dough while it's baking, it will puff up and become something like pita bread instead of matzah," says Vogel. "So we have to put holes in the dough to let the air out."

The children drape their dough over a stick, bring it to the head table, and roll small, spiked metal rollers over it.

All that remains is the baking.

"A real matzah bakery," says Vogel, "has huge brick ovens with lots of burning wood to make very hot fires. The baker puts the cakes of dough on a long, flat paddle, swings it around and slides it into the oven, then flips it over, so there's a line of dough on the oven's surface. He does this again and again until he has an oven full of dough.

"Because the oven is so hot and the dough is so thin, it takes less than a minute for it to bake into matzah," he continues. "If the matzah stays in the oven too long, it burns. It becomes black and inedible."

Next to him, a façade with paper flames stand in for the brick oven. Rabbi Dovid Abba Mochkin, meanwhile, slides the flattened dough into the oven and waits. While the matzah bakes, the children watch a video about the Ten Plagues.

"This brings it to life for them," says parent Carolyn Spanjer about the event.

After a few minutes, Mochkin emerges from the kitchen with a box of hot, handmade matzah. The two rabbis make sure each child has one. But before anyone takes a bite, the group says a special prayer for children around the world, and the rabbis give each child a coin for them to put in a special charity box.

For his part, Vogel reminds them that the display is just a "model bakery" and the matzah they're eating is not kosher for Passover: "So make sure you eat it all before Passover."

Afterwards, the rabbi says that the model bakery is a "hands-on experience that provides a real thrill and a great education. Both adults and children participate."

Says student Michelle Hollenberg: "It was really good and I learned a lot. The most fun part was when we made the matzah."

Start a Discussion