Most of us don’t remember it, but once upon a time Chanukah was not widely known. Back then, giant menorahs did not glimmer outside the Plaza Hotel on Fifth Avenue, or in front of the White House on the Ellipse, or at the foot of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. Young kids and teenagers did not stop people on the corner of Hollywood and Highland in Los Angeles or amid the lights of Times Square with a chipper “Happy Chanukah!” and thrust a box containing a tin menorah, colorful wax candles and a dreidel or two in their hands.

Back then, Chanukah was a holiday that took place behind drawn shades, in the privacy of the home. Until, that is, the winter of 1973—exactly 50 years ago—when the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, launched Chabad-Lubavitch’s Chanukah awareness campaign.

“There is a special advantage in the mitzvah of the Chanukah lights,” he explained at the farbrengen gathering held on 20 Kislev, 5734 (Dec. 15, 1973), just four days before the start of the holiday, “for when a Jew kindles a menorah literal light emanates from it, and illuminates the street.” Therefore, he continued, it was incumbent on everyone to “ensure that every Jewish home has a menorah on all eight nights of Chanukah.” If a person did not have a menorah, the Rebbe added, one should be sold to them at a token price or gifted to them, depending on the circumstances. The Rebbe also emphasized the importance of involving children in the joy of the holiday by giving them traditional Chanukah gelt (meaning actual legal tender, not chocolate), gathering and sharing with them the story of the holiday, and making sure they have their own menorahs as well.

Jews had once kindled their menorahs outside their homes, but centuries of persecution had driven them indoors. Those days were over. Starting in America, it was time to bring the light of the menorah out once again to the streets—not only as a reminder that the Jewish people are free of persecution and can enjoy their rights as a minority, but as a universal message of freedom and liberty for all.1

At the end of the gathering, which took place on a Shabbat afternoon, the Rebbe said he was certain those in the room would hold a meeting immediately after Shabbat’s conclusion to make the necessary plans for the Chanukah campaign.2

The Festival of Lights has never been the same since.3

Renewing and Restoring the World

Chanukah, sometimes derisively written off as a “minor holiday,” is nothing of the sort. Rabbi Isaiah HaLevi Horowitz (1558-1628), known as the saintly Sheloh, pointed out that Chanukah contains within it the immense power to renew and restore the entire world. “Just as Creation began with ‘Let there be light,’” he wrote, “so the mitzvah of Chanukah begins with the lighting of candles.”

In Judaism, there is a preeminence in the mitzvahs connected with lighting candles, the Rebbe explained that Chanukah of 1973, “in that the effect of the action, the appearance of lights, is immediately visible … .” While all mitzvahs handed down in the Torah manifest a spiritual light, that is left unseen by the physical eye. Not so with the mitzvahs involving kindling lamps, which fill the home with a tangible light. This includes especially the Chanukah menorah, which according to the law must be placed “at the entrance of the home, outside,” in a way in which “every bypasser … immediately notices the effect of the light, which illuminates the outside and the environment.”

The world was in an especially dark place when the Rebbe launched the Chanukah campaign in 1973. Similar to today, the Land and People of Israel had suffered devastating losses when surrounding enemy Arab armies invaded the Holy Land on Yom Kippur morning. During the first hours and days of the war, Israel’s very existence appeared at risk, and with it the lives of millions of Jews. While Israel eventually turned the tide and pushed the invaders back—the IDF’s counter-offensive reached within 100 kilometers of the Egyptian capital of Cairo and 30 kilometers of Syria’s Damascus—the price was a steep one: Nearly 2,600 soldiers were killed, leaving behind widows and orphans, and Israel’s morale shattered.

Chabad activists had long been engaged in sharing the joys of Torah and mitzvahs with their brethren around the world. In Israel, this outreach obviously included visits to far-flung army bases. “The visitors in flowing beards and black broad-brimmed hats came to the Golan heights [military outpost] armed with traditional Hanukkah jelly doughnuts, brandy, cakes, candy, warmth and good humor,” The New York Times reported in December 1972, “all of which helped them achieve their objective … . They described themselves to a reporter as soldiers of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson of Brooklyn, spiritual leader of the worldwide Lubavitcher movement. He had enjoined them, they said, to get soldiers to pray in tefillin, the head and arm phylacteries that Jewish men are required to wear for their weekday morning devotions.”4

Up until 1973 there hadn’t been a particular modus operandi for Chanukah outreach, but now there was. Once again, the Rebbe placed a special emphasis on the Jewish soldiers serving on the frontlines of the still-ongoing war. Referring to Israel’s soldiers by the ancient term neturei karta, or “guardians of the city,”5 The Rebbe directed his followers to visit them wherever they were stationed. “They are the representatives of the entire Jewish people, and hold the privilege of shielding the Jewish people with their bodies and souls,” he explained. It is therefore vital that there be a “Chanukah menorah on every base and outpost, even in a place where there is but one soldier, and certainly where there are many soldiers” and that the menorahs be kindled all eight nights of the holiday, each night by another soldier.6

The Rebbe asked that Chanukah gelt be distributed to the soldiers as well and that those visiting them share words of Torah. In addition to the menorahs, each base or outpost should also have a pushke, or charity box, where they could fulfill the mitzvah of charity from the Chanukah money they’d been gifted (something the Rebbe underlined children should do with the money they received from their parents as well).

“It is particularly vital to visit the homes of war-widows and orphans,” the Rebbe continued, “to brighten their homes with the light of the Chanukah candles kindled by the mothers and their children, in addition to sharing words of consolation with them.” A similar effort, he said, should be made with injured soldiers and their families.

A Brighter Life

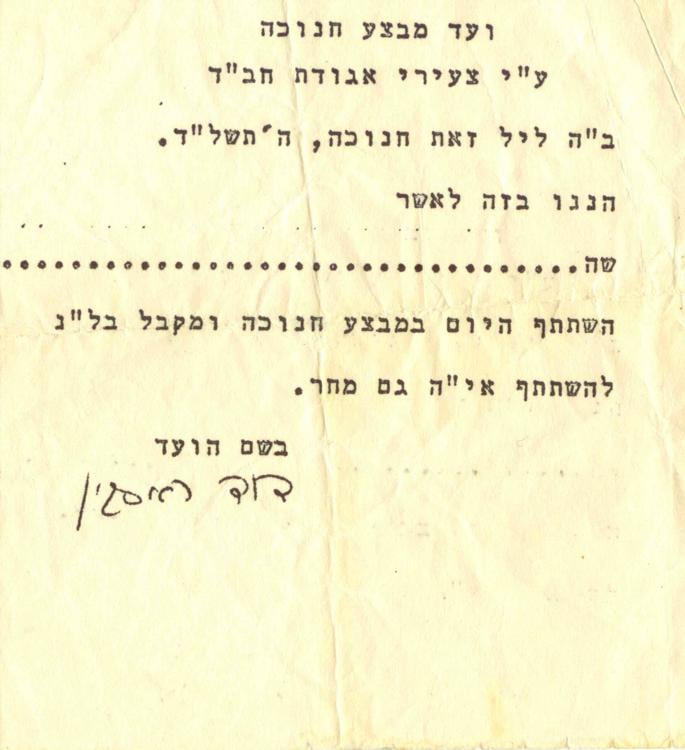

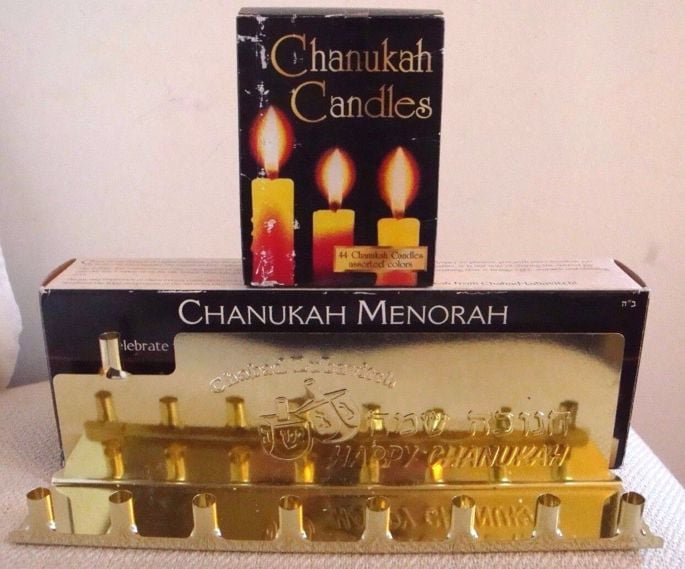

The Rebbe announced his new campaign five days before Chanukah. The meeting the Rebbe suggested take place that evening was indeed held, and within two days, Rabbi Dovid Raskin of the Lubavitch Youth Organization of New York was able to inform the Rebbe that they’d found a metal-stamper and were in the process of producing 10,000 tin menorahs.7

The metal-stamper’s name was Tibor Kupferstein, a Holocaust survivor originally from Budapest whose factory fulfilled U.S. military contracts. The Lubavitchers asked him to come up with a light and inexpensive menorah that would be easy to distribute. “They asked me if I understood what to do, and I said, ‘Yes, I would take a piece of this, and a piece of that, and make something very good for them,” Kupferstein told The New York Times in 2009. “The first one I made was too sharp, so I made it softer.”

He took his factory off of his military contracts and began making menorahs 24 hours a day. “[The Lubavitchers] told me they were going to give it out for free, and I thought this was a very good idea,” he recalled. By the end of Chanukah, Kupferstein had churned out 60,000 menorahs.

Every night of the holiday—early on Friday, when the menorah must be lit before sunset, and later on Saturday night, when it must be kindled after nightfall—Chabad volunteers, young and old, spread throughout New York City to distribute the menorahs. They knocked on doors, visited stores and stood on street corners. (The Rebbe later gave Chanukah gelt to anyone who’d participated in the campaign, proof of which was required in the form of a signed note from organizers). Some of the tin menorahs were also shipped to places like Los Angeles and Miami, where they were given out. By the end of the holiday, all 60,000 menorahs were gone.

A similar effort was seen in Israel, where the IDF flew Chassidim on military transports to bases on the Suez, deep in the Sinai, and the way up north to the Syrian border, to share the Chanukah light and cheer. After all, the menorah tells the story of the victory of a small band of Maccabees against a mighty empire trying to crush the Jewish people on the battlefield.

“Jews have always been a ‘small minority among nations’ and are no match for the nations of the world in terms of physical and material power,” the Rebbe wrote in a Chanukah letter a few years later. “But in the realm of the spirit it is just the reverse; the spiritual strength of 'voice of Jacob' subdues 'the hands of Esau' … . Furthermore, the victory of the spirit is not limited to the spiritual realm, but brings about a victory on the battlefield in the ordinary sense, ‘the deliverance of the mighty into the hands of the weak, and of the many into the hands of the few’ … .”

It was that Chanukah, too, that the public menorah-lighting was born—in a way. As Rabbi Shmuel Lipsker recalled in a 2014 interview with Chabad.org, that year he and a few yeshivah student friends stationed themselves on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan to give out the menorahs. They wanted something that might grab the attention of the thousands of New Yorkers rushing by them. “We decided we’d build a large menorah and bring it with us,” Lipsker recalled.

So they built a simple menorah out of two by fours with a cinder block base, and schlepped it to Manhattan. “The whole afternoon we were announcing that we’d be lighting our menorah at 5 p.m.,” he explained. “Now, you have to remember, this was before public menorah lightings; the concept didn’t exist. It was such a huge attraction. We were giving out menorahs, and more and more people were gathering around us. By the time we lit our menorah … we had a huge crowd. It was unbelievable—just a knockout.”

By the next year, a Chabad rabbi was kindling a public menorah outside of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. A year after that, in 1975, Chabad’s representative in San Francisco and a legendary rock promoter teamed up to construct the world’s first giant menorah, a 25-foot mahogany menorah that still goes up in the city’s Union Square. By 1979, U.S. President Jimmy Carter was lighting Chabad’s giant menorah outside of the White House, since designated as the National Menorah.

Half a century later, Chabad’s Chanukah campaign has touched literally millions of Jews and billions of people around the world. Each year, Chabad erects giant menorahs in public places from Berlin to Buenos Aires, Vancouver to Vermont. It distributes more than 700,000 menorah kits and 2.5 million Chanukah guides in person, or via the mail.

“Let us pray,” the Rebbe wrote in a 1980 letter addressed to all participants in public Chanukah menorah lightings in the United States, “that the message of the Chanukah Lights will illuminate the everyday life of everyone personally, and of the society at large, for a brighter life in every respect, both materially and spiritually.”

Start a Discussion