Rabbi Nisson Pinson, a Russian transplant to North Africa who helped shepherd Tunisia's Jewish community through five turbulent decades, died Monday in his late 80s. Discrepancies among family accounts pin his age between 86 and 89.

Born in Russia at the height of Communist oppression, Pinson knew little of Jewish freedom in his early years. While he learned in an underground cheder, or Jewish school, his father, Nachum Yitzchak Pinson – a Lubavitch Chasid who struggled to keep the spark of Judaism alive behind the Iron Curtain – was exiled to Siberia where he later died.

After his father's arrest, Pinson joined the small exodus of Jewish students to Samarkand in Uzbekistan, where the KGB was reportedly more lax in their enforcement of bans against the practice of Judaism. He learned in an underground yeshiva there and later directed it with Rabbi Mendel Futerfas.

While in Samarkand, he married Rachel Raskin, the daughter of Rabbi Yitzchok Raskin, a Lubavitch activist who was killed by Soviet authorities for spreading Jewish observance.

Following World War II, the Pinsons smuggled themselves out of the country and headed towards France, eventually stopping in Brunoy. They prepared immigration documents for a move to the United States, but put their plans on hold when the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, requested in 1952 that they assist Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries providing education opportunities for Morocco's Jewish community.

In 1959, they moved again, this time to Djerba, Tunis, where they were asked to establish a Jewish school system based on the one Lubavitch started in Morocco.

Under the direction of Rabbi Benjamin Gorodetsky, Lubavitch activities had already been going on in Tunis for seven years, but together with the Pinsons, the group solidified the burgeoning interest in more-substantial Jewish education into a school.

Prior to their arrival, families would join together to hire an instructor for their children. The Pinsons and Gorodetsky thus worked with the Jewish community in changing some of the educational norms, first by offering classes to the veteran teachers employed by the community. At the request of the Pinsons, the country's rabbinate created a curriculum and purchased the necessary buildings for what would become the Ohr Hatorah day schools.

Owing to Arab and Muslim antagonism against the young State of Israel in the early 1960s, the local Jewish community – which once numbered a quarter of a million Jews – dwindled to just 47,000. Israel's victory in the 1967 Six Day War further reduced Tunis' Jewish population as families fled North Africa for Europe, the United States and Israel. Of those that remained, many were among the poorer of the country's Jews and lacking in the means for receiving a Jewish education.

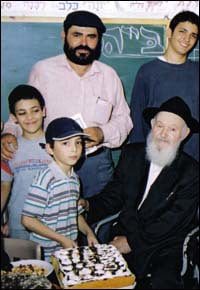

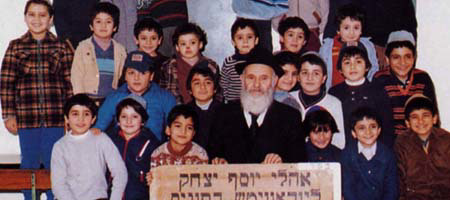

To combat the growing danger of Jewish assimilation, the Pinsons gathered Jewish teens to continue their education at the Oholei Yosef Yitzchak Lubavitch high school.

A Life of Hardships

Pinson's legal predicament caused him many hardships, from not being able to buy a home to not being able to leave the country, not even for his son's wedding in New York. Eventually, though, he was allowed to attend festivities surrounding the nuptials after the actual wedding. At a Chasidic gathering at Lubavitch World Headquarters in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, N.Y., the Shabbat after the wedding, the Rebbe directed that one of the meals be in honor of the new couple.

"The Rebbe felt my pain," said Pinson.

He related in one of the interviews last year of what his wife told the Rebbe about his troubles during a private audience in the early years of their being in Tunisia.

" 'We are already used to the fact that our calls are being listened to, but recently found out that conversations that we have in our home are being listened too,' " he said his wife mentioned to the Rebbe. The Rebbe reportedly replied: "It is worse there than in Russia."

But despite the difficulties, he and the rest of the Jewish community maintained their precarious status because of the protection of the Tunisian government. During times of Muslim unrest, the government would dispatch armed guards to protect the synagogues. In a country that once was headquarters for the terrorist Palestinian Liberation Organization, they lived continuously between accommodation on the one hand and downright hostility on the other.

"While the Jews all over the world were dancing in 1985 following [Israel's] successful bombing in Tunis of a PLO base, the Jewish community in Tunis was in a real danger," Pinson related last year.

But through the most difficult of times, the Pinsons remained in Tunis on the instructions of the Rebbe; their presence encouraged many in the Jewish community to remain in Tunis. The schools they started, which Nisson Pinson continued to run up until the day of his passing, educate hundreds of students every year.

Rabbi Nisson Pinson was scheduled to be buried in Jerusalem on Wednesday. He leaves behind his wife Rochel Pinson and five children: Daughter Tsherna Matusof, co-director of Chabad Lubavitch of Cannes, France; daughter Faige Hecht, a Chabad-Lubavitch emissary in Nice; son Rabbi Yossef Yitschok Pinson, director of Habad Loubavitch of Nice Côte d'Azur; son Rabbi Shmuel Pinson, co-director of Ohel Menachem in Brussels, Belgium; and son Rabbi Nachum Pinson, a teacher in the Lubavitch seminary in Brunoy.

Start a Discussion