Reb Michel Raskin, an unassuming pillar of kindness and hospitality who survived the ravages of Stalinist oppression and the horrors of World War II to become an iconic bridge between Chassidic life in Soviet Russia and America, passed away on Dec. 26 (22 Tevet). He was 92 years old.

A host whose table was a banquet for the stately, a refuge for the lonely and a model of traditional Jewish hospitality, Michel Raskin served as the patriarch of the extended Raskin/Laine family. His home in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., was always filled with guests, including distant relatives and an array of strangers who were provided with a warm bed, after a hearty meal accompanied by Chabad Chassidic wisdom, stories and song.

Proprietor of a popular neighborhood store on the main commercial thoroughfare in Crown Heights, he opened Raskin’s Fruit and Produce in 1959 on the corner of Kingston Avenue and President Street. It remains one of the neighborhood’s oldest shops, and generations of customers and passersby recall Raskin warmly greeting everyone with a smile, whether in the store, or especially in the warmer months, on the street right outside.

“His handshake could crush mountains; his compliment could take you to the mountaintop. He dominated every room he entered, yet you could barely notice he was there,” wrote his grandson, Rabbi Getzy Markowitz, a Chabad-Lubavitch emissary in Montreal, Canada. “Zeide was an optimist, always expressing gratitude to G‑d. Every grandchild believed that he or she was his favorite. We were all obsessed with him; we loved him so much.”

Children and grandchildren describe how it was often impossible to find an empty bed in the Raskin home, which was always hosting guests—from great rabbis to vagabonds, all who were served with respect.

“I never heard the word chesed (‘kindness’) or ‘guest’ used; rather, all were referred to as ‘good friends,’ ” said Markowitz, describing the atmosphere at the Raskin home.

A Childhood of Chassidic Values Amid Soviet Oppression

The oldest of four brothers (Sholom Ber, Chaim Dovid and Benzion), Yechiel Michel was born in Leningrad on Nov. 15, 1929 (12 Marcheshvan) to R’ Aharon Leib and Doba Raiza Laine. Laine descended from R’ Peretz Chein (1797-1883), a Chabad Chassid known as “Peretz the Great,” whose lineage traced back to 11th-century Spain, and before that to the house of Shealtiel, the son of Jehoiachin, the penultimate king of the Davidic dynasty, who was exiled to Babylonia by Nebuchadnezzar in the sixth century BCE.

Through the centuries the Chein/Laine family had proudly upheld Jewish tradition, but Soviet oppression was such that young Michel’s parents had little choice but to send him and his brothers to the local Communist state school. Michel’s parents and grandparents, however, worked to imbue the boys with Jewish and Chassidic values at home, and thereby continue the chain stretching all the way back to King David.

Raskin’s father always came up with creative excuses for the boy’s absence on Saturdays. When filling out school registration forms, he insisted on using his son’s Hebrew name saying that “if he did not maintain his Jewish name and identity, the gentiles would remind him of it.”

The late 1930s were a terrible period in the Soviet Union, as Stalin embarked on his Great Terror, arresting, imprisoning and/or executing millions of men, women and children. In particular, Michel witnessed the February 1938 sweep of arrests of prominent Chabad Chassidim in Leningrad, including Rabbi Elchonon Dov “Chonye” Marozov and Rabbi Yitzchak Raskin, most of whom were never seen again.

A Jew Is Different

Most summers during his childhood, Michel and his family would travel to the town of Rudnya, not far from the village of Lubavitch, where his grandfather Rabbi Yehoshua Laine (1881-1942) served as rabbi and shochet, a kosher ritual slaughterer. It was said that even the non-Jewish townspeople in Rudnya spoke Yiddish.

The time Michel spent with his grandfather played a large role in shaping the young boy’s Jewish outlook, he would later recall. On one occasion, his grandfather took him along to observe a shechita, the ritual slaughtering of livestock, and the young Michel felt faint at the sight of the blood. His grandfather said that it was important for the boy to witness the act so that he would internalize that “Jewish food is prepared differently.”

On another occasion, his grandfather took Michel along to witness the ritual preparation of a body for burial, called taharah. He dismissed the murmurings of disapproval by his fellow Chevra Kadisha members, saying that it was important for the boy to witness the event so that he would appreciate that not only does a Jew live differently but also that “a Jew leaves this world differently.”

Rabbi Yehoshua Laine and most of the Jewish inhabitants of Rudnya were exterminated by the Nazis in 1942.

Avraham Avinu of Gorki

As the German army advanced towards Leningrad, Doba Raiza Laine took her four children east to the city of Gorki (Nizhny Novgorod) to the home of her father, Rabbi Shlomo Raskin (1885-1944), where they remained for the duration of the war, along with other Raskin relatives.

R’ Aharon Leib, remained behind in Leningrad to assist in the defense of the city, where he perished of hunger during the German Wehrmacht’s 872-day siege of the city.

Gorki was an important industrial and military center for the Soviet Union. It was nicknamed the “Soviet Detroit” and its industries provided vital equipment for the Red Army during the war. Consequently, the city was a major target for German Luftwaffe bombers who wreaked havoc on the lives of the residents.

Gorki was also a major destination for Polish Jews and other refugees fleeing the front. The situation in the city itself was dire, with food and medicine scarce as much of it was diverted to the war effort. Every day, members of the Raskin family would wait by the train station seeking Jewish refugees and offer them whatever food they managed to come by. Decades later, as Michel Raskin would drive his fruit delivery truck through the streets of Brooklyn in the wee hours of the morning, survivors who recognized him would recall the legendary care and hospitality of Rabbi Shlomo Raskin during those dark years in Gorki.

One day, Michel’s mother and aunt found a Jewish refugee lying in the street, left for dead. They managed to drag him to the Raskin home where they slowly nursed him back to health. Grateful to the family, he remained to serve as a melamed, a Jewish-studies teacher, for the young Raskin boys.

During one German bombardment, this teacher was asked why he did not feel a need to seek shelter. He responded that “bombs will not fall on the home of (our forefather) Avraham,” referring to the great hospitality exhibited by Rabbi Shlomo Raskin. The Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn of righteous memory, once described Rabbi Raskin as a role model of kindness and as one who was on a lofty level with regards to the mitzvah of hospitality.

After the war, the teacher, Rabbi Shlomo Rosen, went on to serve as the head shochet (“ritual slaughterer”) for the London rabbinate.

From Gorki to Brooklyn

In 1946, the Laine family left the Soviet Union during the “Great Escape,” joining the 1,000 or so Chabad Chassidim who fled the Soviet Union in an organized, clandestine exodus. They left using forged Polish passports made out to their mother’s maiden name, which Raskin and two of his brothers continued to use for the rest of their lives.

The family spent some time in the Pocking DP Camp in Bamberg, Germany, where Michel befriended U.S. servicemen who gave him his first bottle of Coca-Cola. The boy was so excited that he saved it to show his family, only to discover that the soda was now flat as the fizz was gone.

The family then settled in Paris for a few years before immigrating to the United States in 1953. While in Paris, Michel worked hard to support his family. Being the oldest brother, he bore the most responsibility and filled the capacity of a father figure to his younger siblings. He also spent some time learning in the newly-established Chabad Yeshiva in Brunoy, a suburb of Paris, where he developed a relationship with the famed mashpia Rabbi Nissen Nemenov (1904-1984), who he says taught him the importance of humility.

In New York, the Raskins settled in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn before moving to Crown Heights. The Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—would often express interest in the wellbeing of the Raskin orphans.

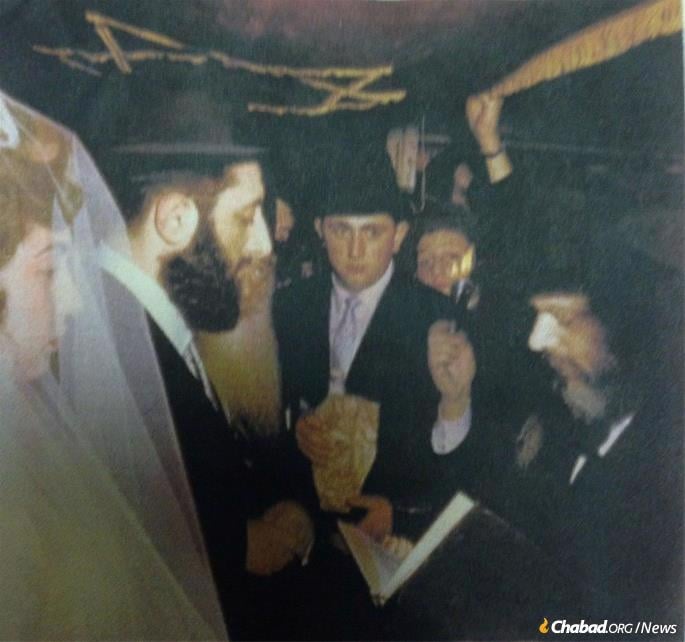

When Michel became engaged in early 1956 to Danya Rubashkin, the daughter of R’ Getzel Rubashkin (1899-1983), he asked the Rebbe to officiate. The Rebbe stipulated it would be on condition that Michel grow his beard.

Between his engagement and wedding, Michel traveled to Montreal to study at the Chabad yeshivah for a few months, and the Rebbe advised him to send his fiancée photos of himself to acclimatize her to his new look. The Rebbe told Rabbi Menachem Zeev Greenglass (1917-2011), the mashpia in the Montreal yeshivah, that he was fortunate to be able to teach a young student with such kabbalat ol (the unequivocal acceptance and commitment to the yoke of G‑d.) Michel and Danya were married in September 1956.

‘Your Store Should Always be Full’

In 1959, Raskin opened his fruit and vegetable store at its present location. The Rebbe’s wife—Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka Schneerson, of righteous memory—was a regular customer, and her orders were often delivered by the Raskin children, who fondly recall their encounters with the kind and regal woman known to them simply as “Mrs. Schneerson from President Street.”

During a Shabbat farbrengen in 1959, shortly after the store was opened, the Rebbe turned to Michel and told him to make a l’chaim on a full glass of spirits so that “your store should always be full.”

At the time, the Raskin family lived in a small apartment above the store at 1411 President St. It was directly across the street from the apartment of the Rebbe’s mother, Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, of righteous memory (1880-1964), whom the Rebbe visited daily. On one occasion, Rebbetzin Chana told Michel that his black 1949 Cadillac reminded her of the “black raven” vehicles used by the Soviet NKVD agents who arrested her husband Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Schneerson, of righteous memory (1878-1944), exiling him to Kazakhstan, and asked that he not park it within her sight.

One Shabbat afternoon, an ambulance was summoned to transport the Rebbetzin to the hospital, but they refused to proceed before being paid in cash. Without hesitation, Michel ran inside his home to get the money. That same day, the Rebbetzin passed away. When her body was brought back to her apartment, the Rebbe asked Michel to bring his store’s old-fashioned broom as it is custom to place a dead body on straw—a material generally not easy to come by in urban Brooklyn.

Raskin would fondly recall how during Simchat Torah of 1962, when the Rebbe taught the melody of Stav Ya Pitu, he turned to Michel in Russian requesting that he translate the tune, which consists of Ukrainian, Yiddish and Hebrew lyrics, to the Chassidim gathered at the Rebbe’s synagogue for the festival.

In 1977, Raskin purchased a large, stately home at 1355 President St. (“Doctors’ Row”) from New York Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm. The house would become a center of community hospitality and Chassidic gatherings.

For many decades, Raskin maintained a weekly study session with Rabbi Pinchas Korf at his home on Shabbat mornings.

In the words of Markowitz, Raskin was “an icon whose business was a welcome center and whose home was an oasis; host whose table was a banquet for the stately and a refuge for the lonely. A son robbed of his youth, a brother turned breadwinner, a husband of unconditional love, a father and zeide who could stretch nachas to no limit.”

In addition to his wife, Raskin is survived by their children: Arik Raskin of Brooklyn, N.Y.; Gutel Edelman of Deerfield Beach, Fla.; Mashie Markowitz of Brooklyn, N.Y.; Avremi Raskin of Melbourne, Australia; Zeldie Treitel of Montreal, Canada; and Shalom Raskin of Brooklyn, N.Y.; in addition to grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He is also survived by his brothers, Dovid Laine and Benzion Raskin of Brooklyn, N.Y.

Join the Discussion