NEW HAVEN, Conn.—The message on our shul’s WhatsApp group announcing, in caps, a MITZVAH OPPORTUNITY caught my attention. I admit to sometimes skimming or even ignoring such messages during a busy week, as they are usually about an upcoming class, a special Kiddush, or a kosher restaurant from out of town making a special delivery this week to our community. But “mitzvah opportunity” sounded important and even a bit time sensitive.

Nonetheless, I ignored it for a day or two. I was sure one or two of the retirees would find the time for this 10 a.m. erev Shabbat mitzvah—not the best time to do anything but prepare for a Shabbat that comes in at 4:09 pm. But the text of the message kept playing over and over again in my mind:

Hi, all. Help is needed for a minyan for a funeral this Friday morning. Leonard Dipsiner, who was raised here in New Haven, just passed away at age 99 and has no immediate survivors other than his niece in NYC. His great niece is a friend of ours. The family would like to ensure that there is a minyan at his funeral. Can anyone assist?

When: Friday, Dec. 10, at 10 a.m.

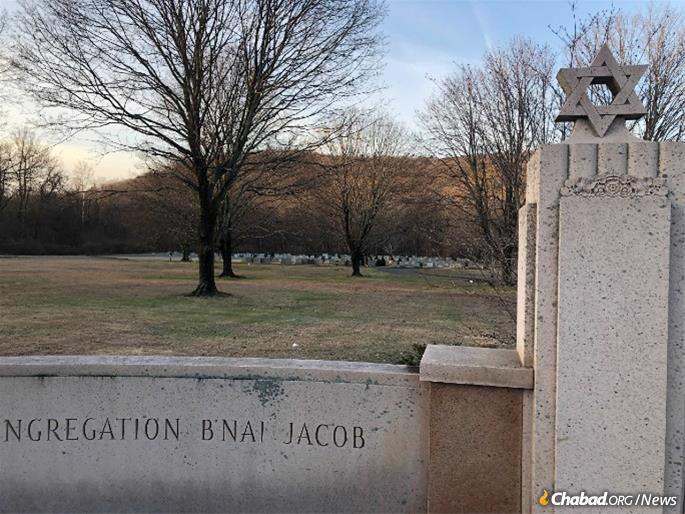

Place: B’nai Jacob Memorial Park (near SCSU)

If you can help with the minyan, please let me know

I began to picture this Jewish man—one who graced this earth for nearly a century—going to his final resting place without the proper respect, the kavod hamet, owed to everyone.

At our shul’s daily minyan midweek, I asked Len, a retired journalist and editor whose wife, Sue, had committed him to attend (via her response on the WhatsApp group), if he knew how the minyan was coming along. He had no idea.

Unsure that there would be a quorum at the gravesite, I reposted the “mitzvah opportunity” again on the WhatsApp group. This time, Aniko indicated that her husband Andy, who survived the Holocaust in Hungary as a child, would be there. No other replies, though a few more details emerged:

... He was raised here in New Haven but spent most of his life in Atlanta, but the family plot is here.

David, the friend kind enough to post this request, also wasn’t sure how the minyan was shaping up and suggested I write to the great niece, Rachel.

Reaching Out to Yale and Yeshivahs

In the meantime, others got on board. Someone from the shul posted a message on the board of another shul. Miriam, a Yale graduate student, shared the request within the Yale community. Ben, a young physician completing a fellowship at Yale quickly replied that he would come. Another wrote, “I will message a few people.”

The niece, Rachel, was relieved when I explained that I work part time at New Haven’s Yeshivas Beis Dovid Shlomo and would be willing to reach out to mesivta’s menahel, Rabbi Yosef Lustig. The busy menahel replied within seconds to my WhatsApp. Without hesitation, he said he’d have three students waiting downstairs at 9:40 a.m. for pick-up in my old blue Ford Windstar minivan.

As I was driving to the yeshivah to pick up the students, I received a nervous call from the niece, Rachel. She was concerned that we might not have a minyan. Due to a miscommunication, she was under the incorrect assumption that the other Chabad school in town had also been contacted.

As a result, I had told two people that we didn’t need them. Nevertheless, both were willing to be “on call.” Ronnie, the Yale mashgiach (kosher-food supervisor) was willing to come with 10 minutes notice if needed on this busy erev Shabbat on campus. Another Yale student had offered to miss class to attend the funeral of a stranger—I had told him we would be OK without him. Now I wasn’t so sure.

As Rachel drove up the Merritt Parkway to the cemetery, and as I drove from home to the yeshiva, we both did a quick calculation and realized we may indeed still be short. My first thought was to call the two “stand-bys”—until I realized that I was two minutes from the Chabad yeshivah!

I suggested to Rachel that I call Rabbi Lustig and ask for “two more.” We quickly did the math again and agreed that six post-bar mitzvah males in my car (five students and me), plus the officiating rabbi, plus two men from the shul, plus a cousin of Rachel’s mother would bring us to 10. Rabbi Lustig agreed, as long as I could give the two additional students five minutes to get ready.

A Meis MItzvah

In the car, while waiting for our final two, I asked the three students—from Baltimore, New Jersey and Florida—if they knew what we were going to be doing. They answered, “A levaya.” A funeral. When I asked if Rabbi Lustig had provided additional details, they said no. “It is a funeral for a 99 year old man with no family.” “A meis mitzvah!” one exclaimed, referring to the biblical imperative to attend to the remains of a dead person—especially one with no relatives.

The other two boys boarded the car and we drove to the cemetery, less than 10 minutes from the yeshivah, nestled between buildings of Southern Connecticut State University and at the foot of West Rock Ridge. On this short Friday, the students would also go out in the community as they do every Friday—on mivtzaim (missions/visits)—to offices, stores, senior citizens housing, offering to wrap tefillin, sharing words of Torah, and wishing fellow Jews they encounter a good Shabbos. And this packed day was after being up until 4:30 a.m. for a farbrengen. They made sure I knew it was the 5th of Tevet.

On this date in 1987, a United States Federal Court judge issued a decision in favor of Agudas Chassidei Chabad (“Union of Chabad Chassidim”) regarding the ownership of the library of the Sixth Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn. The Rebbe urged that the occasion be marked by purchasing, repairing and studying sefarim, Jewish holy books. For this reason, the yeshiva students were up from 11:30 p.m. to 4:30 a.m. the night before, learning words of Torah from their teacher, Rabbi Yosef Rivkin, the yeshiva mashpia.

When we arrived at the cemetery, the guys surveyed the landscape. We walked past the makeshift podium and under the tent erected by the funeral home. Without being told, they instinctively knew to remain standing, leaving the seven seats for elderly guests. A local rabbi officiating the funeral chanted some Psalms and shared some details of the long life of the deceased. He noted that the person who knew him best would soon share more details. A 40ish man with a slight Irish accent began his remarks by noting that he referred to Mr. Dipsiner as Uncle Len.

A Yale Graduate and Military Photographer

“Uncle Len was my godfather. He never married. He never learned to drive. He went to Yale Law School, then opened an antique store in New Haven. My brother and I loved the many cool objects in his store. When we were little, he bought us Legos. When we got older, the gifts became school tuition, car payments, help with houses. Uncle Len moved to Atlanta to be close to his closest friend, our father, Ralph.”

The crowd was intrigued A man with such a rich life story. And few blood relatives. The only non-Jew in the crowd knew the most about the deceased. “He used to tell us Chucky stories when we were growing up, which seemed part fiction and part autobiography. As I got older, I wanted to learn more. And I kept asking.”

Morgan’s persistence paid off. He learned that Dipsiner had been an aerial photographer during World War II, stationed in Belfast, Ireland—just 100 miles north of Dublin where Morgan now practices law and works as a musician. “He would lean out of the underside of planes and photograph enemy camps.” Morgan sensed there must be more. And he kept asking. Years later, Mr. Dipsiner shared the story of how he and fellow American soldiers went to Dachau after the liberation of the camp on April 29, 1945, by the 42nd and 45th Infantry Divisions and the 20th Armored Division of the U.S. Army. They liberated approximately 32,000 prisoners. Dipsiner was responsible for chronicling what they saw in both photographs and videos. This was not an easy or pleasant undertaking. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website, “As they neared the camp, they found more than 30 railroad cars filled with bodies brought to Dachau, all in an advanced state of decomposition. In early May 1945, American forces liberated the prisoners who had been sent on the death march.”

Morgan asked Dipsiner if he still had any photos or video. He did. Morgan suggested he donate them to the Jewish Historical Society of Greater New Haven. He did. Ironically, the museum is no more than half a mile from his final resting place. Morgan looks forward to the day when he can share this important first person account with his now 8-year-old daughter.

As the rabbi was concluding, his niece asked to speak. She wished to thank the people who came out today to help a stranger have a proper send off. She thanked the older shul members but especially the yeshiva students. “This is true chesed shel emet, an act for which you can never be repaid,” she said.

The rabbi concluded with Kaddish and explained the custom of beginning to shovel dirt on the coffin to assist in the burial process. After a few minutes, the attendees walked to their cars. But not the yeshivah students, who wanted to finish covering the deceased with dirt.

They were told that they needed to wait until the tent and chairs were broken down, all cars were moved and the cemetery crew could come to hoist the very heavy cover on the gravesite. They waited patiently. One quietly asked if I could call the yeshivah to make sure there was water to wash their hands upon return to school. Two others sensitively asked the niece for the Hebrew name of the deceased. “He has no family to say Kaddish. We will arrange for Kaddish to be said at the yeshiva.” She promised to get it to me. The boys now know that Leibel Moshe ben Ephraim Fishel will never be forgotten.

The cemetery crew delivered two additional shovels. The five boys and I stayed another half-hour. We shoveled and shoveled. The boys discussed the halacha (Jewish laws) of burial. “Which direction is the head? We need to make a mound with the dirt so it is high in the middle and slopes down. We need to use every bit of dirt. Let’s pick up the boards to make sure all of it goes in the grave.”

As we left the cemetery, I expressed my gratitude. They were already on to the next important mitzvah—fanning out around New Haven with pre-Shabbat business to conduct. One is a regular on my street. I will never forget these boys. These teenagers and their teachers have a lot to teach the community through their actions—about the importance of showing up and answering with a quiet and unhesitating “yes.” Thanks to them, I am sure that 99-year-old Mr. Dipsiner can rest in peace.

Join the Discussion