Razel Wolvovsky was many things to many people.

To the hundreds of children she taught over her decades as a preschool teacher, she was the loving, imaginative morah who made Judaism come alive at the most formative stage of their lives. To others, and there were many, she was the hostess whose Crown Heights, Brooklyn, home was as good as theirs on visits to the hub of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement—the place where there was somehow always room to sleep, eat, have a cup of coffee or a listening ear. And then there were the countless beneficiaries of her many extracurriculars, which were in fact a part of her daily routine: She was a matchmaker who paired hundreds of young couples; a bikur cholim (caring for the ill) volunteer who gave people rides to appointments and cooked meals to their exact specifications; and a friend, neighbor and community member who went out of her way to interact with everyone around her, always adding some touch no one else thought of.

Wolvovsky, who passed away on Nov. 21 (18 Kislev) at the age of 66 after a years-long battle with an illness, did it all—with her husband Monya’s (Mordechai) tireless assistance—while serving as a hands-on mother to 11 children of her own, a fact that never failed to impress the many she encountered. Later, as her children married and many of them established Chabad centers from California wine country to the hills of Tuscany, Italy, she became an active member of each of their growing communities, forming relationships with people based not on externalities but a connection of the soul.

“She saw something in me and was always able to tell me things I needed to hear,” wrote Andrea Rubenstein, a member of the Chabad of Sonoma County community in Northern California led by Wolvovsky’s son and daughter-in-law, Rabbi Mendel and Alti Wolvovsky. “She was one of the guiding lights in my return to Judaism. I will miss her in a way words cannot express.”

This ability to see something in each individual and have just the right word or gesture for them, never gratuitous or expecting anything in return, made Razel Wolvovsky a powerful force for good far beyond her immediate surroundings.

The Paris-Born Daughter of Holocaust Survivors

Odel Razel Wolvovsky was born in 1955 in Paris, the oldest of 10 children. Her father, Rabbi Avraham Dovid Wilhelm, was a Transylvanian Holocaust survivor whose war experience included a spell at Auschwitz. Her mother, Chana Rivka, came from a Lubavitcher Chassidic family that had escaped the Soviet Union using falsified Polish passports in 1946. After meeting and marrying in post-war France, Razel Wolvovsky’s parents immigrated to the United States in the late 1950s, settling near the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Wolvovsky grew up in Crown Heights, where she attended the Lubavitcher girls school, Beth Rivkah. The Rebbe had long urged young couples to strike out for distant locales and serve the Jewish community, and so when she met and married Israeli-born Monya Wolvovsky in 1974, the young couple immediately headed out to serve as Chabad emissaries in San Diego. From there they moved to Milwaukee, where they spent six years running youth activities at Lubavitch of Wisconsin. Though close to four decades have passed since the Wolvovskys’ time in Milwaukee, their groundbreaking work with young people—Monya energetically running the Gan Israel day camp, while Razel devoting herself to Chabad’s preschool—is remembered to this day.

“She had this warmth and joy, and she took our nascent preschool and helped bring it to the top of the page in Milwaukee,” explained Devorah Shmotkin, who co-founded Lubavitch of Wisconsin with her husband, Rabbi Yisroel Shmotkin, in 1968. “Everything she did was thought-out, and she attracted people with her genuineness and polish. You have to understand, it was a long time ago, and Chabad preschools were new. What she did here became the model not only in Milwaukee but in general.” The Wolvovskys returned to Crown Heights in 1982, but the two would maintain their friendship for the next 40 years.

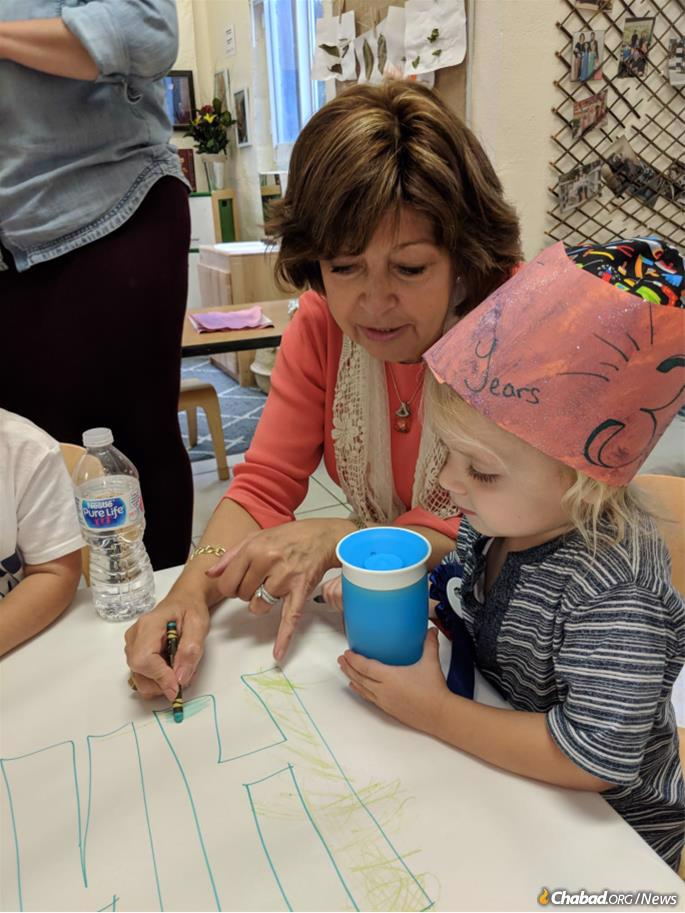

Back in Crown Heights, in the early 1980s Wolvovsky started a new preschool which, with the Rebbe’s blessing, she named Gan Chinuch (though most knew it as Morah Razel’s.) It was here that for the next three decades Wolvovsky nurtured generations of children—and through her classic Now I Know My Aleph Bais video—passing on to her young students her own deeply held love of Jewish tradition and learning in a way children would remember for years to come. Later, Wolvovsky became the inaugural director of Bnos Menachem girls school’s preschool division.

Her warmth was combined with creative and progressive methods of communicating the lessons to children. “Everything was tangible and touchable, it wasn’t common in the early ’90s,” said one former student of hers. On the Chassidic New Year of 19 Kislev, she’d pull out a treasure box in which she stored a Tanya, the foundation text of Chabad thought, given to her by the Rebbe. If she was telling the story of Jonah, she’d create an interactive Lego display—boat and fish and all. “When I became a preschool teacher 20 years later,” the student said, “I did the same thing, because I still remembered how Morah Razel taught it.”

“ … [T]he Torah likens a human being to a tree,” the Rebbe wrote in a 1965 letter, noting that this lesson pertained in particular to children’s education. “ … When the tree is young, especially when it is still in the stage of a seedling, every good care given it in that early stage, however insignificant it may seem, is an investment which in due course amplifies itself many times, and the full effects become evident in the mature, fruit-bearing tree.

“Likewise is the minute attention given to a child, even where the benefit for the moment appears to be quite small … . For even a ‘small’ benefit may in time turn out to be of a lasting quality and extraordinary proportions, reaching into the daily conduct according to the Torah and Mitzvot … .”

This was a mission Wolvovsky took to heart, and it was apparent in the hundreds of children who passed through her classroom.

A Gracious Hostess in an Authentic Chassidic Home

There are few, if any, communities in the world that host as many guests over any given week or weekend as Crown Heights. The concurrent waves of visitors began not long after the Rebbe’s assumption of leadership of the Chabad movement and has never let up. In the 1950s, Chabad Chassidim from Israel began traveling to New York to spend the month of the High Holidays with the Rebbe. In 1962 came the “Encounter with Chabad” weekend, which saw American Jewish college students from around the country flock to Crown Heights. As the ranks of Chabad emissaries grew, so did the number of guests they’d bring back to Brooklyn to see an authentic Chassidic community in action.

The Wolvovsky home was one of those archetypical homes, Razel opening her doors to Jews from all walks of life at all hours of the day or night. For the 11 Wolvovsky children, pulling out extra tables at the last minute at their mother’s direction was typical for a Friday-night meal. “Just cut the matzah ball in half with the round part on top,” she’d instruct her kids in a pinch. In the days since her passing, the family has received a flood of messages from former guests in their home. “I rang the bell at 3 a.m., and your mother opened the door for me like it was normal,” one said. “When you’re a guest, you usually get a message at some point that it’s time to go,” said another. “I never got that from your mother so I never left.”

A Crown Heights premarital teacher shared that Wolvovsky reached out to her to ask that when she encountered young couples without a family infrastructure in the community to privately put her in touch with them so she could invite them for Shabbat meals and be that support for them.

It was never primarily about the bed or meal but the lasting relationship that was formed. Her son Rabbi Yosef Wolvovsky, co-director, with his wife Yehudis, of Chabad of Glastonbury, Conn., said many community members shared that their Jewish journeys had gone to the next level after spending time with his mother, encountering a dedicated, sophisticated woman whom they could both admire and relate with. Wolvovsky formed connections in her own home and when she and her husband would visit their children’s communities.

“I met her roughly 23 years ago, and it was like a magnet; we formed a lifelong friendship,” said Shelly Schapiro, a member of Wolvovsky’s son-in-law and daughter Rabbi Mendy and Batya Rosenblum’s Chabad of the South Hills in Pittsburgh. “She was incredibly open, inclusive and accepting, and though in a way our backgrounds were so different, we were also so similar.”

Her loss, Schapiro said, was a South Hills community-wide one. David Grossman, a member of her son and daughter-in-law Rabbi Berel and Chaya Wolvovsky’s Chabad of Silver Spring, Md., community shared much the same. “Everyone knew her and felt close to her. Razel interacted with everyone; she and her husband really were a very big part of our community. She’s a hard act to follow.”

Wolvovsky continued her routine of goodness and kindness through her years of sickness, driving people to appointments when she had her own to go to, sending food platters when she could have been receiving them, encouraging others going through similar and always thinking of the other.

“At one point, I was a patient at Sloan-Kettering when Razel was going to Cornell for treatment,” Grossman added. “She finished her appointment and with everything she had going on came across the street to visit me to cheer me up. This is a special person.”

“You can’t overestimate how powerful of an influence she was on so many,” observed her son, Rabbi Berel Wolvovsky. “Without holding a position or a title, she was an institution of her own.”

Wolvovsky is survived by her husband, Monya Wolvovsky, and their children: Batya Rosenblum (Pittsburgh, Pa.); Rabbi Yosef Wolvovsky (Glastonbury, Conn.); Rabbi Mendel Wolvovsky (Santa Rosa, Calif.); Rabbi Berel Wolvovsky (Silver Spring, Md.); Rabbi Shlomo Wolvovsky (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Shmuly Wolvovsky (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Levi Wolvovsky (Florence, Italy); Schneur Zalman Wolvovsky (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Moshe Wolvovsky (Boca Raton, Fla.); Mushkie Gurevitz (Morristown, N.J.); Rishi Lieberman (Lauderhill, Fla.); many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

She is also survived by her mother and siblings.

Join the Discussion