It was the height of the Cold War, 1977. Dr. Bernard Lown—world-renowned Harvard cardiologist, pioneer of the direct-current defibrillator for cardiac resuscitation and co-founder of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW)—was in Moscow. Beginning in the late 1960s, Lown made more than 30 trips to the Soviet Union, especially rare for an American of the era.1

On this particular October evening, the Lithuanian-born Lown and his wife, Louise, were taking in a ballet performance at the Bolshoi Theater, something they did on nearly every trip to Moscow. This was the leisure part of Lown’s itinerary and so he was surprised when suddenly, mid-show, he was summoned to the theater telephone. Little could have prepared him for what came next.2

“Boruch!” shouted the caller in Yiddish, referring to Lown by his birth name. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe isn’t well, you must come to New York now!”

The voice at the end of the line belonged to Lown’s cousin, Rabbi Moshe Binyamin Kaplan, a Chabad-Lubavitch Chassid living in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. It was the holiday of Simchat Torah in New York, when observant Jews refrain from using the telephone. Yet this was life-or-death; Kaplan had spent the preceding 24 hours trying to get through to the Boston-based Lown, finally tracking him down to the Bolshoi.

Kaplan quickly explained what was happening: Two nights earlier, on Shemini Atzeret, the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—had suffered a severe heart attack during the hakafot dancing in his synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, and a second, even more serious one in his office early the next morning. “On a scale of 10, he had the full 10,” Dr. Ira Weiss, the Rebbe’s lead cardiologist, would tell Jewish Educational Media’s My Encounter with the Rebbe oral history project years later. “ ... The Rebbe had a heart attack that involved such extensive damage that in anyone’s normal medical experience one would worry about the possibility of survival and one would almost discount any possibility of functionality at the level of the Rebbe’s.”

Kaplan, knowing that his first cousin Bella’s son Boruch, a.k.a. Bernie, a.k.a. Dr. Bernard Lown, was an important heart doctor at Harvard, was determined to bring him to the Rebbe as soon as possible.3

But that’s just the beginning of the story.

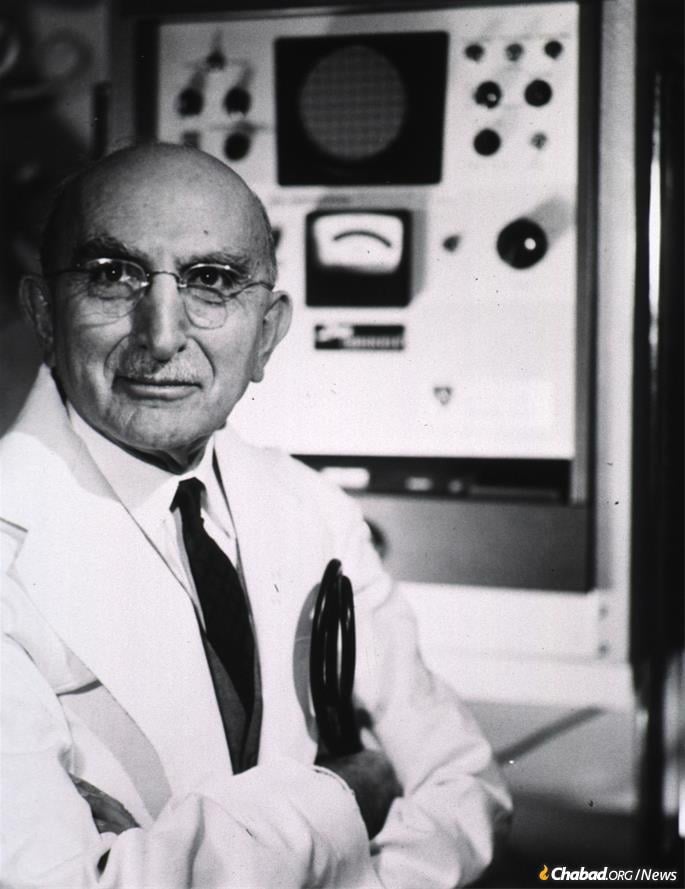

Pioneer

Lown, who passed away on Feb. 16, 2021, at the age of 99, was indeed everything his cousin thought he was. A longtime professor at the Harvard School of Public Health and a top expert on arrhythmia, Lown’s expertise was regularly sought by world leaders. In fact, it appears that on this 1977 trip he was treating a high Kremlin official, likely Mikhail Suslov, a member of the Politburo, chief ideologue of the Communist Party and one of the Soviet Union’s most powerful men. (Perhaps these medical interactions with top figures in the Kremlin is why the CIA, FBI and NSA still refuse to declassify Lown’s files.)4 Among Lown’s other patients were King Hussein of Jordan,5 Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau of Canada and U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

There were many reasons for Lown’s fame, any one of which could have been a life’s achievement. Lown’s early research had uncovered the link between potassium levels and the safe usage of the centuries-old heart failure drug, digitalis. His early investigation of the role that irregular heartbeat, or arrhythmia, played in sudden cardiovascular death made him an expert in a subject not well understood by most in his field. Lown recognized that administering a well-timed shock to the heart could break dangerously abnormal rhythms and restore a normal heartbeat, leading to his 1962 development, together with engineer Baruch Berkovits, of the direct-current defibrillator and his creation of a device called a cardioverter. These advances not only saved many thousands of lives directly, but opened the doors for safer open-heart surgery and the development of the pacemaker.6 A few years later, he became the first to use Lidocaine to treat arrhythmias. When in 1964 he opened a coronary care unit at Boston’s Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, today Brigham and Women’s Hospital, it was one of the first in the world.

In Lown’s own estimate, an even greater contribution to cardiology was the “chair method” he developed together with his Harvard mentor, the great Dr. Samuel Levine. Beginning in the early 1950s, the two discovered that by seating patients with cardiovascular diseases in an armchair instead of lying them down on a bed, gravity would pull fluids in the chest down and allow patients to breathe easier and their heart to recuperate. This simple observation, which they published together in a 1952 paper, “changed the whole course of cardiovascular care,” he explained. Though met by fierce resistance from the medical establishment of the time—bedrest was deemed an unquestionable part of hospital care—the chair method is in wide use today and has saved an immeasurable number of lives.7 This combination of respect for tradition and questioning conventional wisdom, which Lown did in his typically blunt manner, would make him at times a thorn in the side of the medical establishment and become a mainstay of his long career.

In addition to his long affiliation with Harvard and Brigham, Lown also ran a private clinic, and in 1973 started the Lown Cardiovascular Research Foundation, now known as the Lown Institute.

It wasn’t only technical innovations that earned Lown both the commendation and enmity of his colleagues, but his single-minded dedication to patient-centered care. This approach contends that a doctor’s job is to heal their patient, not merely use the latest technology to treat an individual body part, and so the patient’s input, life story, position and comfort all play an important role in their own healing process. By placing the emphasis on the emotional and psychological well-being of the patient, it also invited the patient into a relationship with their doctor, allowing them, for example, to share information that could very well be vital to a successful outcome. Lown applied this holistic approach in his own practice and stressed it with generations of his students.

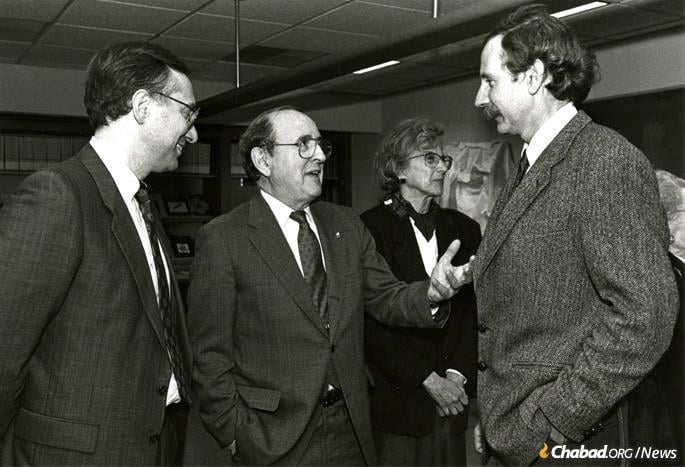

“He said to all of us, ‘You have to be very attentive,’ ” recalls Weiss, a leading American cardiologist who spent 1971 to 1973 as a Lown cardiology fellow at the Harvard School of Public Health and the Brigham. “So even the small details that might be overlooked when reviewing a person’s background or history can offer an important clue … and be the difference between a successful and, G‑d forbid, an unsuccessful doctor. I took that to heart, and it made a very big impact on me.”

Lown “was one of my mentors, and he taught me and other people the humanistic approach to medicine,” adds Dr. Louis Teichholz, also a former student of Lown’s who became a pioneer in the field of echocardiography and joined Weiss in caring for the Rebbe following the heart attack. “There’s a quote of his that I have with me: ‘One treats not the heart, but a human being who has a heart.’ Dr. Lown’s whole approach was treating the patient, and he was one of the people who formulated my career in terms of patient-centered care.”8

Even as the medical establishment moved further away from the age-old vision of doctors as healers, turning them instead into technical diagnosticians, Lown continued to use his bully pulpit to sound the alarm.

“It seems to me that medicine has indulged in a Faustian bargain,” he warned. “A 3,000-year tradition, which bonded doctor and patient in a special affinity of trust, is being traded for a new type of relationship. Healing is replaced with treating, caring is supplanted by managing, and the art of listening is taken over by technological procedures. Doctors no longer minister to a distinctive person but concern themselves with fragmented, malfunctioning biologic parts. The distressed human being is frequently absent from the transaction.”9

Much more than just a way of making the patient feel better about themselves, he’d tell anyone who listened, respecting the patient and involving them in their own care was a surer avenue to success.

Yeshivah to Medicine

Bernard Lown was born Boruch Latz on June 7, 1921, in the village of Utyan (Utena), then-independent Lithuania. At the time of Lown’s birth, the village was more than half Jewish. His father, Nison Latz, was born to a Chassidic family in Utyan,10 studied at the famed Lithuanian yeshivah of Slabodka (just outside Kovno), and was later chairman of the Jewish community’s committee. His mother, Bella (Beile Hinda, née Grossbard), came from a distinguished rabbinical family in Filipow, Poland. The Latz name was Americanized to Lown by Nison’s older brother (and Bernard’s father-in-law), Philip (Feivish) when he came to the United States in 1907, and adopted by Nison when he followed suit.

The Latzes were deeply religious in the old country, and Lown and his brothers grew up studying in their local cheder before going on to yeshivah. On one visit to the Soviet Union in the late 1960s or early ’70s, Lown’s government handlers facilitated a return trip to Utyan. Bernard and Louise were greeted by one Kalman Meyer, one of the town’s few survivors; Lown remembered him from childhood as the town plumber.

“Now he was wizened, white-haired, and slight, though still vigorous. He spoke a brisk Yiddish,” Lown wrote. “Without introduction, he held out an old frayed photograph of a kindergarten class and pointed to a little boy. ‘Who is this?’ he asked me. I looked closer at the photograph and recognized the faded image of my brother Hirshke beneath Kalman-Meyer’s finger. ‘Then you are Boke!’ he exclaimed, a happy glint in his eyes. Indeed, my childhood nickname had been Boke, a diminutive of my given name, Boruch.”11

The vast majority of Utyan’s Jews were exterminated after Hitler’s invasion in 1941, members of Lown’s family included, the murders for the most part not committed by the Germans but by their Lithuanian neighbors. “We take pride in greeting Bernard Lown, now a world-famous doctor,” Kalman Meyer solemnly declared at the Utyan gathering in Lown’s honor. “It was just in an instant of luck that he and his family were saved from fertilizing the Lithuanian soil. Many others were not so fortunate. His close friend Chaimke, who was a gifted poet, wasn’t so fortunate ... . ’ ” He went on, listing many of Lown’s childhood contemporaries. “ ‘The world lost many Bernard Lowns. We must not forget them, for our own sake.’ ”12

Nison and two boys—Bernard and Harold, or Boruchl and Hirshele—left Utyan in March of 1935, with Bella following with the other children in 1936.13 Their cousin Moshe Binyamin Kaplan’s son, Rabbi Nochem Kaplan, recalls hearing that before the boys left Lithuania, Bernard’s yeshivah teacher begged Bella that her son continue studying Torah in America, for he had the ability to be a “gadol b’Yisrael,” or “a giant in Israel.” Later, seeing Bernard’s success in medicine, Bella recalled the teacher’s words and said, in Yiddish: “If not a giant in Israel, then a giant in medicine.”

The family initially settled in Lewiston, Maine, where Lown, then 14, attended high school, enrolling before he could speak English.14 In the New World, the Lowns quickly “Americanized,” which many Jewish immigrants of the era took to mean dropping religion in totality, and Bernard and his siblings were not raised religious at all. Lown would however retain a strong, staunchly secular Jewish identity. His son, Fred Lown, explains that his father was fluent in Jewish history, folklore and long recalled the Talmud of his youth. He also had “a repertoire of probably 5,000 Jewish jokes that he would tell colleagues and patients.”

There were elements of his childhood, however, that try as he might, he could not shed. “His English was impeccable, and he was unbelievably articulate and fluent,” says his son. “But he still had that kind of Eastern European Jewish shtetl accent.” He adds with a laugh: “Whenever someone mentioned that, he bristled because he thought he had lost it.”

Lown would also ascribe his passion for medicine and the philosophic outlook he adopted at least partially to his “Jewish heritage,” with its “rabbinic tradition [and] love of books.”15 Yet this did not spill into practice. “My father was not religious in any sense of the word, and even though I come from a whole multi-generational rabbinical background, we were never religious,” explains his son. In fact, the only reason why Fred had a bar mitzvah and went to Hebrew school was because his grandfather was a big figure in a temple and insisted on it, not because of his father.

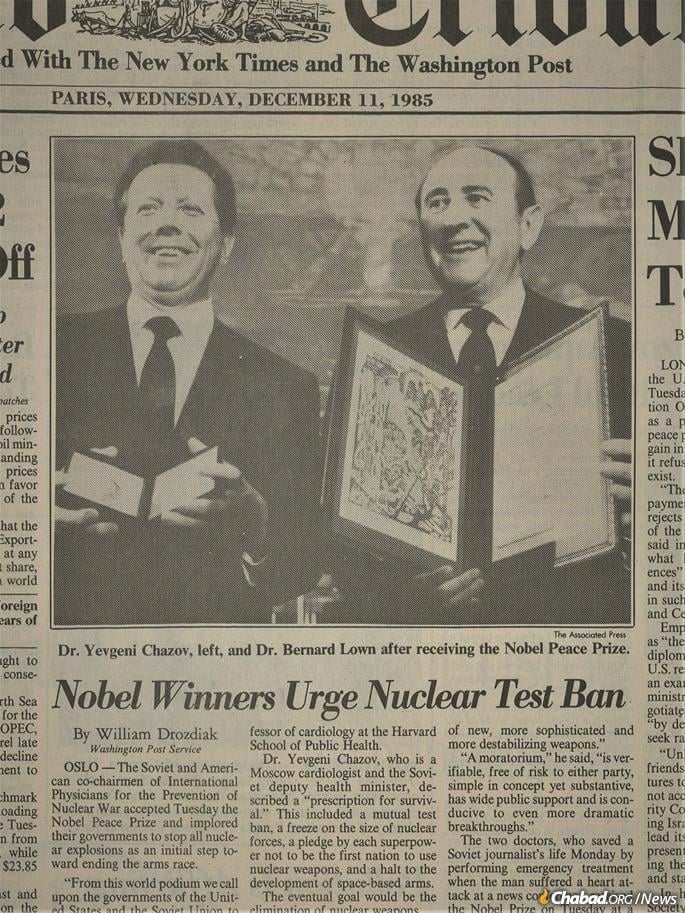

A self-described man of the left, early in his career Lown began to worry about the existential dangers of nuclear war, and in the early 1960s he started an organization called Physicians for Social Responsibility. It was Lown’s activism that led to his first invitation to lecture in the Soviet Union back in 1968. Twelve years later, Lown created the IPPNW together with top Soviet Dr. Yevgeny I. Chazov, a Communist official who was personal physician to high-ranking Kremlin figures, including Mikhail Gorbachev. Lown’s activism made him an actor on the world stage but also brought on accusations that he was a closet Communist or at the least a Kremlin tool. These attacks did not subside after he and Chazov accepted the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize on their organization’s behalf.16

But now the doctor was in Moscow and on the phone with his Chassidic cousin, Kaplan, who stemmed from the side of his mother’s family that had remained religious after arriving in America. Kaplan pleaded for Lown to come to the Rebbe as soon as possible, and Lown agreed.

Shemini Atzeret, 1977

Just a few days earlier, everything had appeared fine. After prayers on the morning of Hoshana Rabbah, Oct. 4, 1977, the Rebbe, 75-years-old at the time, stood for hours at the door of his sukkah distributing lekach honey cake to those who had not had the opportunity to receive it before Yom Kippur. Shemini Atzeret, one of the most joyous holidays of the year, would begin that evening, followed the next night by Simchat Torah. The Rebbe’s joy and vitality during this holiday was transcendent, and the resulting exuberant atmosphere in his synagogue, palpable.

Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, however, the Rebbe’s wife, knew that something was amiss. That morning the Rebbetzin rang the Rebbe’s secretariat saying her husband did not feel well and asking they attempt to lighten the Rebbe’s schedule. Nevertheless, after praying the afternoon mincha service and seeing that a new line for honey cake had formed outside his Sukkah, the Rebbe made another distribution before going home for just a few minutes.17 Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, one of the Rebbe’s secretaries, would later recall the Rebbe looking particularly pale when he drove him that day.

The first three of the evening’s seven hakafot—in Chassidic circles the traditional dancing with the Torah scrolls is held on the evenings of both Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah—went off without a hitch. Then came the fourth hakafah, when the Rebbe’s face suddenly turned white. First resting on his lectern, then sitting down on his chair, leaning back and closing his eyes, the sudden change threw the crowd into chaos. People began rushing out of the synagogue to allow in air, and windows were smashed open. Still, the Rebbe insisted on completing the Hakafot, which a much-diminished crowd hastened to do. Returning to his room, the Rebbe refused to eat or drink anything until going out to the Sukkah to make kiddush on wine.18

Aside from the doctors onsite, Krinsky called the chief surgeon of a nearby hospital, who arrived and made a cardiogram; the reading was abysmal, and the doctor said there was no choice but for the Rebbe to go to a hospital. But the Rebbe dismissed the idea, saying he would only be treated in 770.

As the hours ticked by, a procession of cardiologists came and went, each confirming that the Rebbe had suffered a major heart incident and needed to be in a hospital. Sometime in the early hours of the morning the Rebbe had a second, more extensive heart attack. At around 6 a.m. the Rebbetzin came over to Krinsky and asked for an update. Krinsky responded that the situation was dire and some of the doctors were insisting the Rebbe be sedated and taken to the hospital.

Telling the story over years later, Krinsky would recall the sheer strength the Rebbetzin demonstrated at that moment. An intensely private person, the Rebbetzin had dedicated her whole life to supporting her husband in a way no one else could. Now, standing to lose all she had, she maintained that the Rebbe’s wishes be adhered to. “All my life that I know my husband, never for an instant was he not in total control of himself,” she told Krinsky. “I cannot allow the doctors to” go against the Rebbe's will.

A moment later she turned back to Krinsky. “Rabbi Krinsky, you know so many people, you can’t find a doctor for my husband?”

That’s when, all of a sudden, things began to come together. Like a flash, Krinsky remembered a book on heart rhythm analysis he had seen on the Rebbe’s desk a few months earlier sent to the Rebbe by Krinsky’s brother-in-law in Chicago, Rabbi Herschel Shusterman. The book was written by a brilliant young cardiologist named Ira Weiss, a former congregant and Hebrew school student of Shusterman’s.19

Building a Coronary Care Unit

It was early morning when Weiss got Krinsky’s desperate call describing the severity of the situation. The Rebbe, he explained, had not rejected medical care, but wanted it to take place in 770 itself, a position backed up by the Rebbetzin. Krinsky wanted to know whether this was possible.

“I’d known about the Rebbe from when I was a little cheder student in the 1950s in Chicago,” Weiss explained to me. “We were not from the kind of household that were Chassidim … but I had at least the wherewithal to know that one does not trample on the things the Rebbe wants to do. On the other hand, you’re obliged as a doctor to do whatever you need to do, even if the patient tells you otherwise if there’s only one way to save him.”

Though young, Weiss was already acclaimed in his field. In 1967, at the age of 23, he graduated first in his class from Northwestern University Medical School. That summer, as he began his two-year residency at Massachusetts General Hospital, Time magazine profiled him in a piece on young medical school “wonders,” asking the question: “How young can a doctor be?”20 Weiss then spent two years at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., doing research and writing his book on the deciphering of irregular heart rhythms—this during a time when cardiac monitoring was still a relatively new idea—before returning to Boston as a cardiology research fellow under Dr. Lown at the Harvard School of Public Health and the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital.

Over this time, in part due to Lown’s example, he had embraced a patient-centric approach to medicine, which he brought with him to his Chicago-area practice. (Years later Weiss would gift Lown a book on the Jews of Lithuania, inscribing “To my rebbe of cardiology.”) On the phone with Krinsky early that morning, Weiss suggested that Krinsky set up the equivalent of a coronary care unit at 770.

“The idea to take care of the Rebbe in this way was sparked by my being able to see how this was applied by my teachers,” explains Weiss. In Boston he had seen special setups made in the homes of people like members of the Kennedy family, and knew that his teacher, Lown, had gone to similar lengths to treat the Baroness Pauline de Rothschild.21 “Being exposed to Dr. Lown and being exposed to my mentors at the Massachusetts General Hospital, who had the same obligations to take care of special people in the privacy of their own quarters, I told Rabbi Krinsky at the time, that this has been done, and my teachers have taught me this.”

That’s where the conversation ended. A moment later the phone rang again. It was Krinsky. “Dr. Weiss, why don’t you come out here and help us do this?” he asked.

Weiss immediately agreed, but calculated it would take him at least a few hours to get from Chicago to Crown Heights. A competent cardiologist who thought along the same patient-centric lines needed to get to 770 fast. That’s when Weiss remembered that Teichholz, a more senior former colleague at Peter Brigham Hospital in Boston, had just transferred to New York to teach and become head of cardiology at the Mount Sinai Hospital. Weiss hung up with Krinsky and called Mount Sinai immediately.

“As you can imagine, calling a hospital and asking for a certain person to come to the phone doesn’t get you that person right away,” he recalls. The operator “attentively listened to what I was saying, and noting how frantic I was, ran down the hall to the cardiology unit and pulled Dr. Teichholz to the phone. And she put me on with him in that single call.”

Teichholz had only vaguely known of the Rebbe before Weiss’ call, but on hearing the situation cleared his schedule—Teichholz was set to start a tour of lectures on echocardiography—and instead agreed to head to 770 immediately.

“Someone met me at Mount Sinai and I had a police escort going the wrong way down Flatbush Avenue at 90 mph,” Teichholz remembers with a chuckle. Arriving with advanced equipment, Teichholz went straight into the Rebbe’s office and stabilized the situation.22

“The fact that I was lucky enough to reach Dr. Teichholz without delay made it possible to intervene effectively, just in the nick of time,” Weiss says, noting that by the time he got there a few hours later the Rebbe’s heart rate was normal and his heart rhythm regular. This was being accurately measured by a telemonitoring device that Teichholz had brought with him, advanced technology that at the time would not have been readily available in most hospitals. “Dr. Teichholz’s prompt interventions were done with a lot of skill and a lot of immediate thinking. Had I not been able to reach Dr. Teichholz, it may not have worked at all.”

Both Weiss and Teichholz, without hesitation, dropped what they were doing because they understood that the Rebbe’s medical care had to be performed in a way that he could continue the vital work of leading the Lubavitch movement and world Jewry, and influencing and teaching humanity at large. Their ability to discern this not only on a personal level but on the medical one drew from lessons they had both been taught by Lown: a physician must take into full consideration each patient’s particular needs, in this case a leader of the Jewish people.

“I came down every day from work, met with Dr. Weiss [who spent a month straight at the Rebbe's side] and Dr. Lown [while he was there], and we took care of the Rebbe,” recalls Teichholz. “Thank G‑d he did well and survived for many years.”

It should be noted that Lown would likewise be an influence on the third cardiologist to join the team, the late Dr. Lawrence M. Resnick. In the aftermath of the Rebbe’s heart attack, Resnick successfully petitioned the U.S. Navy to transfer him from his posting at Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii to Brooklyn so he could help treat the Rebbe, and arrived in Crown Heights a few weeks later. Resnick, who would become known as an innovative researcher in hypertension at the Cornell Medical Center in New York, met Lown at 770 and consequently spent two years as a Lown cardiology fellow at Harvard.

From the Bolshoi to 770

On the afternoon after the Rebbe’s heart attack, Rabbi Nochem Kaplan returned to his parents’ home to find his father on the phone. “I’m calling my cousin Baila Hinde [Bella],” his father told him. “We need to bring Bernie to the Rebbe.”

Naturally, Bella Lown was surprised to hear her religious first cousin’s voice on the phone on the holiday. “Vos tustu Moshe?!? [“What are you doing Moshe?!?”], she cried. “Haynt iz yontiff!!” [“It’s the holiday!!”] On hearing what had occurred, she informed Kaplan that her son was in Russia. She told him her brother Chaim (Hyman) Grossbard, a professor at Columbia University in New York,23 would have Lown’s contact information. Kaplan then called Grossbard and the same scene played itself out, before the former dictated Dr. Lown’s Moscow hotel information.

“All of these calls took hours of work,” remembers the younger Kaplan.24 Moshe Binyamin Kaplan spent the whole next day of Simchat Torah trying to get patched through to the Moscow hotel, employing the broken Russian of his youth when he finally was. The Moscow hotel in turn told him that the Lowns were at the Bolshoi. When he got through to the Bolshoi, Kaplan began yelling that he was in America, had an emergency and needed to be put through to Dr. Lown immediately. This worked, and Lown was called to the phone mid-act, agreeing to come to New York as soon as he could. Lown and Louise immediately set about rearranging their travel schedule and headed to Brooklyn.

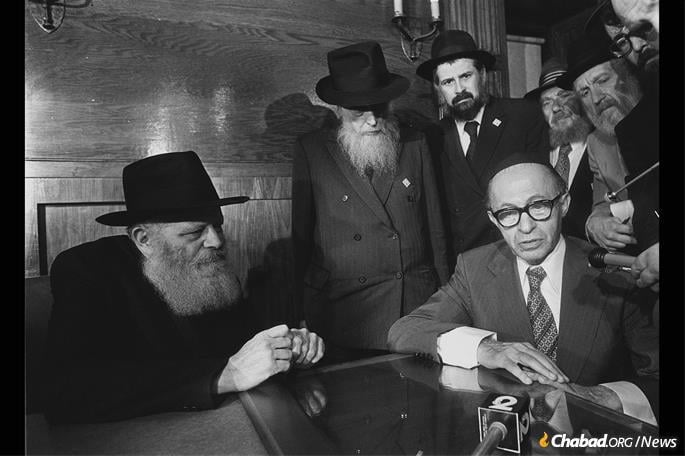

On Sunday, Oct. 9, 1977,25 the haggard Lowns arrived at JFK airport via Helsinki. Rabbi Nochem Kaplan picked them up at the airport, brought them to his parents’ home, and then drove Lown to 770, where the cardiologist spent the rest of the day. Krinsky recalls Lown spending some time with the doctors and secretariat before heading into the Rebbe’s office.

By the time Lown arrived in Crown Heights the Rebbe was recovering in 770, where Weiss, Teichholz and the team assembled around them had created the equivalent of an advanced coronary care unit in the Rebbe’s office.

“I was actually astounded that he was there to help us,” says Weiss about Lown’s sudden arrival. That Lubavitchers had somehow tracked down Bernard Lown did not very much surprise Weiss, who recalls them somehow procuring whatever he needed no sooner had he said the word (including advanced monitoring equipment from NASA.) Simultaneously, it was such a tumultuous time that he never did end up finding out how Lown, who as far as he knew was in Russia, suddenly walked through the doors of 770 Eastern Parkway.

A Shared Philosophy

Likely unknown to Lown at the time was the fact that the Rebbe had for decades been urging and teaching a remarkably similar model of medicine as Lown’s. This would undoubtedly be a topic of their long, private discussions at 770.

In public talks, correspondences and private audiences dating to the beginning of his leadership in 1950, the Rebbe emphasized the vital importance of preventive care, patient empowerment and the doctor-patient relationship. He regularly advised those turning to him for help to seek second-opinions, worried technology getting in the way of the doctor-patient relationship, and emphasized the immense power of positive language and a healing environments in a medical setting—for example, advising that hospitals in Israel not be called a beit cholim, “house of sickness,” but a beit refuah, a “house of healing.”26 The Rebbe likewise counseled that doctors not play G‑d by taking away a patient’s hope. A physician was G‑d’s agent. Technology and medical know-how were tools of their trade, but the power to heal stemmed from G‑d’s blessings and His blessings only.

“‘The emotional support of the doctor, the human being, is most important,’” Israel Prize-winning physician Dr. Mordechai Shani recalled the Rebbe telling him during a 1976 private audience. “‘While technology can be a very helpful tool, it cannot become a replacement for listening and caring.’’” The Rebbe, Shani explained, “expressed the worry that technology might distance the doctor from the patient.”27

The physician has an important role in healing, but the patient had to be allowed and encouraged to do their part in the process.

The similarity in the Rebbe and Lown’s philosophy thus made it unsurprising that Lown embraced the Rebbe’s decision to remain in 770. “He said immediately that the Rebbe was absolutely correct,” Krinsky remembers.

Kaplan picked up Lown late that first night in 770. In the few minutes before retiring, an exhausted Lown shared that the Rebbe had been correct to avoid the hospital after his initial heart attack because standard protocol in the hospital would have been to sedate him, and in that state it would have been unlikely the Rebbe would have survived his second heart attack. The Rebbe had insisted that Chassidim celebrate the rest of Simchat Torah with even more joy despite his condition, and Lown noted that he believed the Rebbe's physical condition was positively affected by being in an enviornment where he was able to hear the sounds of the all-night singing and dancing from the synagogue below.

While the vast majority of doctors had rejected this idea, it took someone like Lown, sure of himself and his vast medical knowledge but cognizant that there was more to healing than science, to give 770’s makeshift hospital his stamp of approval.

Weiss recalls Lown, as the most senior and eminent cardiologist there—a matter not only of his standing but his particular personality—being more at ease conversing with the Rebbe. “When talking to the Rebbe you’re talking to the Rebbe,” Weiss explains. “But Dr. Lown had the authority to have a little bit more of a persuasive dogmatism, and … we were happy he was there.” In general, Weiss says that the Rebbe, as a proponent of second opinions, would consult with Lown as that second opinion, although always sensitive that his other doctors not feel slighted in any way.

“I think he gave the Rebbe and particularly the Rebbetzin a feeling of ‘here’s the senior adult in the room,’” Weiss says. “Dr. Lown didn’t ... throw his hands up and say, ‘What are these youngsters thinking of?!’ He was supportive, and he had a few ideas that were uniquely his, which he presented to the Rebbe face to face when they had private meetings, but he didn’t arrive and decide the whole thing needed to be revised radically.”

Kaplan remembers Lown—who spent about a week in Crown Heights on that first visit—telling him about a conversation he had with the Rebbe. The Rebbe had asked him why this heart episode had taken place now. Lown responded that “until now your will power has driven your body. But after a while sheer willpower simply cannot overpower the body, and your heart could not take the load that you are placing on it.”

It was around then that the doctors, Lown included, and with the Rebbetzin’s full support, began discussing the Rebbe rearranging his schedule. At the time the Rebbe held a public farbrengen at least once a month, on Shabbat, and they wanted the Rebbe to cut down on them. “The Rebbe told Dr. Lown that this was not negotiable,” Kaplan says. “He said ‘Shabbos elevates all people. When I speak to them, I elevate them, and they elevate me, and Shabbos elevates us both, so the farbrengens have to continue on Shabbos.’”28 The Rebbe did not cut down on his public farbrengens—in fact, they increased in number through the 1980s—but for many years wore a telemonitoring device at farbrengens.29 30

Over the next year or so Lown would come to examine the Rebbe about once a month, decreasing in frequency in the years that followed. Brilliant, eloquent, keenly aware of his own abilities and station in life, Lown was not a man easily impressed. And yet over the next four decades he would frequently return to his time with the Rebbe.

Mind, Body and Soul

More than just an added emphasis on the patient’s psychological and emotional well-being, the Rebbe’s approach was ultimately a holistic one, seeing the mind, body and soul as intertwined parts of one whole, none of which could be treated in isolation of the other. The surest way of eliciting positive results came when the physical, psychological and spiritual efforts of both doctor and patient were united in acknowledgement of the Almighty’s promise in Exodus: “For I, G‑d, am your Healer.”

“ ... Surely I don’t need to draw your attention to the fact that the spiritual and physical are connected to each other,” the Rebbe wrote to one doctor. “Medical science also recognizes that the health of the body is linked to the health of the spirit and soul — and not only to the spirit in the simple sense, but also to the Divine soul. It is therefore my hope that when you heal your patients, you also pay attention to their spiritual state … .”

While much of Lown’s approach to healing he adopted from his mentor, Levine, there came to be fundamental elements of his approach that transcended the psycho-emotional and veered straight into the spiritual. One cannot help but wonder how much of this was impacted by his deep interactions with the Rebbe.

Lown’s moving medical memoir, The Lost Art of Healing, written nearly two decades after his initial meeting with the Rebbe, points to a man who believed there was something otherworldly about his field. “The fundamental reality is that the soul is not encompassed by the brain,” Lown wrote. “Medicine cannot abandon the healing of aching souls without diminishing its relevance for the human condition.”31 Echoing many of the Rebbe’s long-held medical stands, Lown writes of “the extraordinary power of words to heal,” and notes that “faith and optimism have life-giving qualities.”32 As for predictions? “I leave prognosis as the very narrow preserve still left to God Almighty.”33

“... I have come to embrace the possibility of miracles,” Lown writes, sounding more like one of the long line of rabbis he stemmed from than the dean of American cardiology. “The contradiction is more apparent than real. Even when cure is impossible, healing is not necessarily impossible. While medical science has limits, hope does not. … The miracles reside in the capacity for comforting and healing.”34

By all accounts Bernard Lown was not a religious man, and yet where the doctor’s role as healer was concerned, it’s clear that he and the Rebbe were in sync. But there was clearly more than just medicine.

“It was interesting that … in spite of his sort of anti-religion philosophy, he was fascinated with the Rebbe and with Lubavitch,” Fred Lown tells me. “This came out in many, many conversations that I’ve had with him over the past 40-50 years.”

Lown was one of the greatest cardiologists of his time. Though a master listener who worked hard so that his patients felt they had his full attention,35 of the many adjectives those who knew him best utilized to describe him, “humble” was not one of them.36 Yet it’s clear he saw something different in the Rebbe.

“There weren’t many people in the course of his life … that he saw that kind of charisma,” says Fred. “I think he understood the Rebbe’s spiritual following on some level that he probably couldn’t even articulate.” In his yet-unpublished memoir Lown describes the Rebbe’s gaze as “penetrating,” recognizing a man who “saw into souls.”

“As a clinician, that’s what my father wanted to emulate … they had that connection,” his son considers. “I can imagine them two sitting there … even in silence, speaking volumes to each other.”

“The Rebbe was the one person who had stirred the conscience and spiritual awakening of world Jewry,” Lown continues in his unpublished memoir. “ … The Torah, given on Sinai, needs a commander no less than the Sinai campaign.”

In 1980, the 30th year of the Rebbe’s leadership of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, Lown wrote the Rebbe a letter congratulating him on reaching this “noteworthy milestone.” “Though an infrequent visitor to your headquarters, and then only for medical reasons, the ambience of serious pursuit and commitment to Jewish religious life has never failed to make a deep impression. Please accept my felicitations and heartfelt wishes for your long continued creative leadership in health and physical well-being.”37

“I take this opportunity to convey to you once again my heartfelt appreciation for helping me reach this ‘noteworthy milestone,’ to quote your letter,” the Rebbe responded two days later. “And while the blessing of health, like all blessings, come from ‘the Healer of all flesh Who works wondrously,’ G‑d chooses His special agents in each case, and as our Sages express it, ‘G‑d chooses a worthy agent for a worthy cause.’ May G‑d grant that you should always be able to bring healing to all who turn to you for your professional help.”38

“... [I]t is a profound privilege to be able to attend this remarkable human being,” Lown wrote on another occasion to Rabbi Zalman Gurary, a Lubavitcher businessman and philanthropist who was also a patient of Lown’s. “I was especially pleased to find him recently doing so well.”39

The Shofar and the Matzah

In late summer of 1979 Lown was attending to the Rebbe when he mentioned he was heading to China as part of a cardiological delegation, and he would be there for Rosh Hashanah.40 The Rebbe inquired whether he knew how to blow a shofar. When Lown said he did, the Rebbe asked whether he would blow the shofar in China if he’d give him one. Lown agreed and the Rebbe removed a shofar from his desk and gifted it to him. Lown followed through on his promise, reporting back to the Rebbe when he returned, who in turn commented that this was the first time the sound of the shofar had been heard in China in many years.41 He kept the shofar as a prized possession until the end of his life.

Which brings us to the shmurah matzah sent to the Lowns every year from Lubavitch World Headquarters, a tradition initiated by the Rebbe himself.

“Every Pesach, a week before, we’d get a big box of shmurah matzah,” explains Fred Lown. “ … My mother would place it on one of her most beautiful pieces of china, wrapped in a gorgeous embroidered napkin, and the shmurah matzah would sit in the center of the table, at every seder.”

It’s not incidental that Lown, the healer, was drawn to the matzah, which the Zohar refers to as “the food of faith” and “food of healing.”42

The tradition began six months after the two first met. The Rebbe’s custom was to distribute shmurah matzah each year on the eve of Passover. Since it was baked that morning and people tend to stick close to home on Passover, the distribution was mostly limited to those in the immediate New York City area. With the Rebbe having returned home from the makeshift hospital at 770 on Rosh Chodesh Kislev, as Passover 1978 approached he was once again outside his office distributing matzah. Towards the end of the distribution, about 4:30 or 5 in the afternoon, Krinsky asked for matzah for himself to use at his family’s seder that evening.

“I don’t know why, but when I went over, I also asked for a piece of matzah for Dr. Lown,” Krinsky tells me. “The Rebbe looked at me, gave me a whole matzah, and asks ‘Will he get it before Pesach?’ What that told me was that no question, the Rebbe wants him to get it before Pesach.”

Passover was mere hours away. Krinsky packed up the matzah as quickly as he could, got hold of a yeshiva student, gave him cash for a cab, and told him to rush to the Marine Terminal in Queens to catch someone boarding a shuttle flight to Boston. On landing, the person the yeshiva student tasked with the mission was somehow found in the packed terminal by Krinsky’s brother, the late Rabbi Pinchas Krinsky, who promptly sped the matzah over to the Lown’s home in Chestnut Hill, Mass., making it back to his own home in Boston’s Brighton neighborhood with just minutes to spare before the holiday.43

“I remember the Rebbe was very pleased that it worked out,” Krinsky says. From that point on, each year Krinsky would send a box of shmurah matzah to the Lown residence. Other than that and mailing out the Rebbe’s periodic personal donations to Lown’s foundation, Krinsky didn’t have a whole lot more contact with Lown in the ensuing years.44 Unbeknownst to him, though, the matzah became an important part of the Lown family’s Jewish life. For Lown, it was not only the matzah that became a tradition, but recalling the man who had sent it to him.

“He spoke about the Rebbe often with family members and close friends, but every Passover, when the shmurah matzah was passed around, it was a story about the Rebbe,” Fred Lown shares. “I remember that vividly from all the seders that I’ve attended … . [My parents] became the reigning patriarch and matriarch of our extended family, and the Rebbe and the shmurah matzah was a central part of it.”

Lown may not have been religious—he was perhaps even anti-religious—but over the course of a long life he communicated an unyielding belief in something higher. He did this in his approach to medicine, in the stories he told, and in the matzah he ate, a love for which he passed on to his children and grandchildren. Fred told me that when he told his son prior to our interview that he’d be speaking to someone from Lubavitch later in the day, his son shot out almost immediately: “Dad, see if you could score some shmurah matzah!” (He did.)

Matzah, the Rebbe explained on more than one occasion, represents the raw spark of faith found within the deepest recesses of the soul. By consuming matzah on the nights of Passover the Jewish soul reconnects with its Creator not on the intellectual or emotional plane but the essential one, where man and G‑d are one.

The Zohar refers to matzah first as the food of faith, and then as that of healing. The order is not random, but a prescription for the ultimate preventive medicine.

“On the first night [of Passover], matzah is ‘the bread of faith.’ On the second night, it is ‘the bread of healing,’” Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of the Chabad movement, explained. “When healing leads to faith, in that a person says, ‘I thank You, G‑d, for my recovery,’ he was, nevertheless, sick. But when faith generates healing, a person is not sick in the first place.”45

It’s a vision of healing Dr. Lown well understood.

Join the Discussion