Second in a two-part series about about the dramatic growth in the use of handmade shmurah matzah in the last 60 years. The first article in the series, “How a New World of Consumers Discovered Handmade Matzo,” is here.

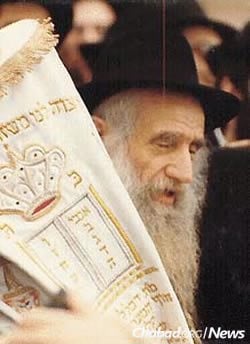

It’s safe to say that when the pious-looking Rabbi Shmuel Dovid Raichik came to Los Angeles in 1948, there weren’t many people there who looked like him.

The Polish-born rabbi had made it out of Europe alive following an unusual path of escape. Raichik had been studying at the Chabad-Lubavitch Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim in Otwock, a suburb of Warsaw, when Nazi troops invaded Poland in September of 1939. Together with a larger group of yeshivah students, Raichik managed to make it to Lithuania, where he and the others obtained transit visas from Chiune Sugihara, Japan’s consul in Kaunas (Kovno), enabling them to cross the Soviet Union and spend the war years in the relative safety of Kobe, Japan, and Japanese-controlled Shanghai.

Kobe had a tiny Jewish community when the 30 Lubavitcher yeshivah students arrived there in 1941. Halfway around the world from home—a home that was in the process of being destroyed—they suffered from fatigue, a drastic change in climate and food poisoning. Still, as Passover approached, they worried: Where would they get wheat shmurah matzah in rice-dominated, faraway Kobe?

The answer was across the Sea of Japan, in the far larger Jewish community in Shanghai, whose chief rabbi, Rabbi Meir Ashkenazi, arranged a special shipment of shmurah matzahs to be delivered to the refugee students. Later that year the entire yeshivah would relocate to Shanghai.

After the war, the group immigrated to America, Raichik included, and in 1948 the sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, of righteous memory—sent the newly-married scholar to California as his representative. Came Passover time in L.A., there was no way that Raichik, who had managed to obtain shmurah matzah in the middle of the war in Japan, would not have the round, traditional matzah at his Los Angeles seder table.

Soon enough, he would become the sole distributor of handmade shmurah matzah on the West Coast. Over the next 60 years, demand for the traditional, round matzah would grow at a rapid rate, and in 2017, according to a survey conducted by Chabad.org, more than 1 million pounds of the handmade variety will be produced in the United States alone.

Transcontinental Matzah Via UPS

The steady growth in demand for handmade shmurah matzah around the world began in early 1954, when the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—encouraged his followers to distribute shmurah matzah to every Jew they came in contact with. Following this call to action, Raichik began receiving packages of hand-baked matzah—this time not from Shanghai, but from Rabbi Yehoshua Korf’s newly-opened shmurah matzah bakery in New York.

Despite the lack of demand within the Jewish community, each year before Passover, Raichik and his sons would go to UPS to pick up the boxes of round matzah.

“Aside from some rabbonim here who got shmurah matzah for themselves, people just had the square matzah until my father began shipping it here,” says Raichik’s son, Rabbi Shimon Raichik of Congregation Levi Yitzchak on North La Brea Avenue in Los Angeles. The elder Raichik passed away in 1998. “They weren’t rejecting shmurah matzah; they just didn’t know what it was.”

One of Raichik’s primary focuses was delivering the matzah to Jewish day schools throughout Southern California, places like Yavneh Hebrew Academy in Los Angeles and Emek Hebrew Academy in the San Fernando Valley. In this way, he ensured that generations of children would learn about the special matzah in school before taking it home and suggesting to their parents that they eat it at the seder.

“My father would walk into principals’ offices and sell them on the idea,” recalls Raichik. “Then the kids had it at their seder.”

Raichik wasn’t alone. At the Rebbe’s encouragement, a handful of rabbis were doing similar things around the country. Beginning at the same time as Raichik, Rabbi Dovid Edelman, the late director of Lubavitcher Yeshiva Academy in Springfield, Mass., began his well-documented matzah distribution route, which over 60 years grew to include massive areas of Western Massachusetts and had him visiting 700 families. Similar matzah-distributing efforts took place in urban centers such as Boston, Baltimore, Miami, Detroit, Minneapolis-St.Paul, Montreal and Houston.

Later, in New York, shmurah matzah was sent by the Lubavitcher Youth Organization to troops in Vietnam.

When President Barack Obama hosted the White House’s first-ever seder in 2009, the matzah was supplied by a young aide from the Springfield area named Eric Lesser. Eric’s father, Dr. Martin Lesser, had been receiving the round matzah from Edelman for decades, and when it came time to making a seder, it was only natural for Eric to bring the real stuff.

“What’s interesting about the emergence of shmurah matzah in American Jewish life is that for most, their immediate ancestors didn’t use it,” notes Jeffrey Gurock, professor of Jewish history at Yeshiva University and author of Jews in Gotham: New York Jews in a Changing City, and more recently, Jews of Harlem. “The Rebbe’s matzah campaign is very important in introducing it, and its authenticity resonated even among Jews who are not particularly observant.”

East Side to the Supermarket Aisle

Yossi Frimerman has been a wholesaler of shmurah matzah since 1976, and is the man largely responsible for getting handmade matzah onto supermarket shelves. Born and bred in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood, Frimerman also remembers going with his father to purchase shmurah matzah on the Lower East Side.

By the time he got into the business, demand had picked up, but the price of American shmurah matzah was still too high for supermarkets to consider stocking it.

“The supermarkets couldn’t understand why a pack of crackers could, even at that time, cost $18 to $20 a pound wholesale,” says Frimerman of those early days. While consisting of only two ingredients, making shmurah matzah is a year-long, time- and labor-intensive process. Just finding a wheat field that has not had rainfall in some time can be difficult, and matzah producers must be in touch with multiple fields in various states, monitoring weather conditions throughout to ensure they get dry but ripe wheat.

Starting with the Pathmark chain, Frimerman began stocking supermarkets in the New York area with lower-priced shmurah matzah imported from Israel, an effort that grew as he penetrated more markets further away from the tri-state area. Some markets expanded faster than others, something Frimerman unhesitatingly chalks up to the locations of Chabad emissaries.

“The entire shmurah matzah market was able to develop first and foremost due to the shluchim,” attests Frimerman. “There was a time when they were the only ones distributing it, often for free or at a loss. They developed the demand.”

Frimerman notes a visible correlation between places with a heavy Chabad presence and successful matzah markets. “It is no coincidence that California buys tens of thousands of pounds of shmurah matzah. You see the same thing in Florida, in places where you can’t attribute its market to the size of its Orthodox Jewish community.”

Frimerman runs a for-profit business, but says supplying shmurah matzah to an ever-growing number of people gives him a sense of fulfillment. In the early days, he made the decision that he would send matzah to anyone who reached out to him, no matter the margins on the sale. Nowadays, he is busiest on the week before Passover, not because it is the most profitable time—large buyers have long finished with their purchases by then—but when all sorts of “matzah emergencies” pop up around the globe. Knowing that the frantic calls will inevitably come, he sets up emergency shipping during that week so that he can turn around last-minute orders in a heartbeat.

As production and consumption of shmurah matzah continue to increase each year, Gurock, a keen observer of American Jewish life, synopsizes the product’s dramatic half-century of growth: “The Rebbe’s dictum ends up at the White House. That’s amazing!”

See the first article in the series: “How a New World of Consumers Discovered Handmade Matzah.”

Join the Discussion