The revered Rebbetzin Chaya Nechama Halberstam, a Nazi death-camp survivor and wife of 47 years of the Sanz-Klausenburger Rebbe, Rabbi Yekusiel Yehudah Halberstam, passed away on April 4 after being in ill health in recent years. She was 96 years old.

A refined woman of dignity and grace, she arrived in the United States after World War II, her parents and seven of her siblings having been murdered in Europe.

It was her brother-in-law, Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl, himself a Holocaust survivor and underground Jewish leader in occupied Slovakia, who suggested a match for the 24-year-old with a fellow survivor: the 42-year-old Sanz-Klausenburger Rebbe. Rabbi Halberstam, who prior to the war had been one of the youngest Chassidic rebbes in Europe, had lost his wife and 11 children to the Nazis—the eldest dying shortly after liberation—himself surviving Auschwitz, Dachau and a death march. The young woman was initially hesitant; he was nearly 20 years her senior. Rabbi Halberstam allayed her concerns, promising that they would live to marry off all their children together.

Indeed, his words came to pass.

Rebbetzin Chaya Nechama Halberstam was born in 1923 to Rabbi Shmuel Dovid and Miriam Leah Ungar, in the city of Trnava (Tarnow), Slovakia, in 1923.

Rebbetzin Halberstam’s father, Rabbi Shmuel Dovid, was a revered Hungarian rabbi and teacher who accepted the rabbinic leadership of the small Slovakian city of Nitra in 1931, where he expanded its small yeshivah, making it famous throughout Europe, and became known as the Nitra Rav.

Prior to accepting the position, a student of his tried to dissuade him from moving to what was a relatively small Jewish community. In a sadly prophetic vision, Rabbi Shmuel Dovid responded to the young man, Rabbi Weissmandl, who would later become his son-in-law, “My heart tells me that there will come a time when the only remaining yeshivah on the continent will be in Nitra. That is where I wish to be ... .”

Indeed, even as World War II began and conditions for the Jews of Slovakia worsened, Rebbetzin Halberstam’s father insisted on keeping his yeshivah’s doors open.

In 1942, Slovakia’s Nazi puppet dictator, the Catholic priest Jozef Tiso, began deporting the country’s Jews to Auschwitz. By the first Shabbat after Passover of 1942, the Jews of Nitra were beginning to be deported.

Rabbi Ungar, working closely with his son-in-law and student Rabbi Weissmandl and in conjunction with other underground Jewish activists, attempted to save Slovakian Jewry. With the aid of a hefty bribe paid to Nazi and Slovak officials, they managed to stave off some deportations until 1944. They also obtained permission from the Slovak government to keep their yeshivah open during those two years; the last surviving one in Slovakia. They constructed hiding places under the bimah (the Torah-reading lectern) and above the bookcases in the study hall in the event of Nazi raids. Often, the warning would come so suddenly that the students and faculty would bolt, leaving their Talmuds still open on the tables. Through this all, Halberstam’s father continued to teach.

After crushing a Slovak partisan revolt in 1944, the Germans occupied the country, ramping up the deportations to Auschwitz. The Nitra yeshivah was liquidated by the Nazis on Sept. 5, 1944. By October, every remaining Jew in Nitra had been deported.

Halberstam’s father, and her brother, Sholom Moshe, had been out of town when the Nazis liquidated the yeshivah. They fled to the forests, spending the winter hiding in mountain caves, subsisting on meager rations. During this time, Rabbi Ungar made sure to observe every iota of Jewish law, not even eating bread if he couldn’t find water to ritually wash his hands. When Rosh Hashanah approached, his primary concern was how they would hear the shofar. His student Meir Eisler, who also accompanied him in hiding, recalled that when kindly gentile farmers would offer them fruit and vegetables, Rabbi Ungar would never accept the life-sustaining offer without first paying them.

Just a month before liberation, on Feb. 9, 1945, Rabbi Ungar succumbed to starvation. In his last moments, he instructed his son on where and how to bury him, and recited his final prayers.

Young Chaya Nechama was deported to the Sereď concentration camp after the Nazis uncovered their bunker and from there to Auschwitz.

“When we got there, I was separated from my younger sister, Hilde Channale, who was sent to the gas chambers,” she recalled in an interview with Ami Magazine. “Four weeks later, there was a selection and I was among a group of women who were dispatched as slave labor to a munitions factory in Bad Kudova, on the Czechoslovakia-Poland border. The women in Bad Kudova were interned at the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. At first we had a foreman who was terribly cruel, but he was later replaced by a woman supervisor who was tolerable.

“One of the girls had a siddur and we took turns using it. But there wasn’t very much time for that. If we weren’t working there were lineups and roll calls, or else we were sleeping from exhaustion.”

They were a diverse group of 23 girls at the camp, many of whom didn’t come from religious families, and Chaya Nechama tried to set an example. She would express certainty that they would be liberated, and go on to marry and establish families, something that was a faraway dream in those bleak times. Her optimism was contagious and helped many of the girls pull through. One young woman, at Chaya Nechama’s urging, would pluck a few strands from her clothing and save a smidgen of margarine each day so she would have an improvised Shabbat candle.

A New Life

Rebbetzin Halberstam survived the war, but most of her family had not. Her father had starved, and her mother was murdered. Her only surviving siblings were her sister Esty, and brothers Yaakov and Sholom Moshe.

In America in 1947, her brother-in-law Weissmandl (whose wife, Halberstam’s sister, Bracha Rachel, and children had perished) suggested the match with the widowed Sanz-Klausenburger Rebbe, who had not only lost his entire family in the Holocaust but the majority of his followers as well.

They were married on Aug. 22, 1947, in Sommerville, N.J., just hours before Shabbat. The wedding was attended by many prominent rabbis of the day, celebrating a renewal of the old home in Europe on American shores. The Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—sent a personal telegram to the new couple with his congratulatory wishes, accompanied by a wedding gift. The festive meal followed on Friday night, after which the Klausenburger Rebbe held his weekly gathering for his Chassidim.

At that first meal as a married couple, while her husband studied in preparation for his weekly talk, Chaya Nechama ate the meal in the kitchen together with the students of her late father's yeshivah, now reconstituted by her brother-in-law in Sommerville—young, orphaned teenage boys, desperate for some motherly love. From that point on, she would work to create the warm and homely Shabbat atmosphere these boys had been denied, after which the young boys would join the older Chassidim at her husband’s tish, the Chassidic gathering at which Chassidic rebbes of Polish and Hungarian extractions share words of Torah, lead the crowd in song and tell timeless Chassidictales.

Rebbetzin Halberstam’s dedication to her husband is well-known in the Sanz-Klausenburg community. She was always careful not to disturb him as he went about his holy duties, even while caring for their young brood. She supported her husband and was at his side throughout the decades in which he embarked on his many communal endeavors, among them an ambitious project that transformed the medical landscape in Israel.

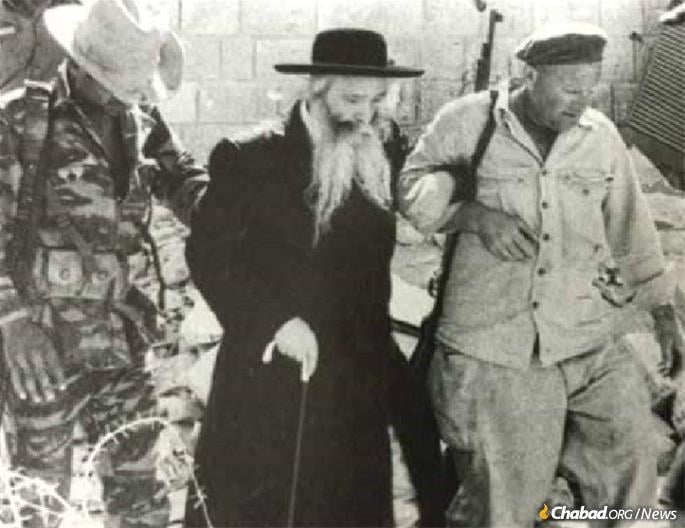

In 1975, her husband established what would eventually grow into the Sanz-Klausenburg Medical Center-Laniado Hospital in Netanya, Israel. The idea was audacious and met with astonishment; what did a Chassidic Rebbe know about hospitals? But Rabbi Halberstam had dreamed of the idea years earlier while in the midst of a nightmare.

“While incarcerated in a Nazi death camps, I was shot in the arm,” the Klausenburger Rebbe explained. “I was afraid to go to the Nazi infirmary, though there were doctors there. I knew that if I went in, I’d never come out alive ... so I plucked a leaf from a tree and stuck it to my wound to stanch the bleeding. Then I cut a branch and tied it around the wound to hold it in place. With G‑d’s help, it healed in three days. I promised myself then that if I got out of there, I would build a hospital in Israel where every human being would be cared for with dignity. And the basis of that hospital would be that the doctors and nurses would believe that there is a G‑d in this world, and that when they treat a patient they are fulfilling the greatest mitzvah of the Torah.”

Rabbi Gershon Lieder, a Klausenburger Chassid whom Rabbi Halberstam appointed as a director at the hospital, later recalled in an interview with Jewish Educational Media (JEM) how Rabbi Halberstam sent him and a committee from the hospital to meet and ask for advice from the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory.

“Don’t feel inferior, and don’t pay attention to what other people are saying about you,” Lieder remembered the Rebbe reassuring the inexperienced group. “You are emissaries of a great rabbi, and even though you will face obstacles, you will succeed.”

In a 2010 interview with Chabad.org, Rabbi Yosef Binyamin Wulliger, another Klausenburger Chassid at the private audience, recalled the Rebbe asking them why the new hospital was called Beit Cholim (the modern Hebrew term for hospital, which literally means “House of the Sick”).

“I would ask you to either call it a ‘House of Healing’ or a ‘Center for Healing’; for one goes to the hospital not to get sick, but rather to heal,” the Rebbe told them. The hospital is known as Laniado-Merkaz Refui (Healing Center) Sanz.

In all this and more, Rebbetzin Halberstam was a life partner to her husband, and was renowned for her own kindness and charitable personality. Her daughter-in-law, Rebbetzin Suri Halberstam of Kiryat Sanz, Israel, recalled for example the time Rebbetzin Halberstam went out of her way to help a family in Union City, N.J. The family had six children and the wife was battling a long-term illness, rendering them unable to make a Passover seder. The Rebbetzin invited the family to spend the holiday with her. And so they did, year after year. After several years, they wished to make their own seder at home again. Sensitive to their plight, the Rebbetzin cooked all their meals and brought it over, along with Passover dishes and cutlery.

Rebbetzin Halberstam was buried in Netanya alongside her husband, who passed away in 1994.

She is survived by their two sons and five daughters, who serve as rabbis and rebbetzins in Israel and the United States, as well as many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Join the Discussion