It was a cold day in the spring of 1979 when 13-year-old Anna Monahemi arrived at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York. She came with a group of 40 Jewish girls—all of them from Iran, each of them alone. Her parents, like those of the other girls, had quietly bought her a ticket to Rome and sent her off, not knowing when they would see her next. There, the girls were greeted, processed and issued U.S. I-20 student visas. Five days later, they were safely in America.

From JFK, Anna and the girls were brought directly to the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., and placed with host families—members of the Chabad-Lubavitch community. This was not the only group of Iranian Jewish children in Crown Heights. Since the end of 1978, planeloads of Jewish refugee children had followed the same path to safety, intensifying after the January 1979 fall of the Shah of Iran and the return from exile two weeks later of the Shi’ite cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. By Passover of 1979, there were 1,000 Iranian Jewish children staying in Crown Heights with families, living in dorms, and studying in schools and classes established especially for them in the neighborhood.

Jews had lived in what was long known as Persia for 2,500 years, and at the time of the revolution, 100,000 of them called it home. They were well-established and successful. But then came the Islamic revolution, followed swiftly, 40 years ago this month, by the Islamist seizure of power. Violence roiled the streets. Threats against Jews were followed by the arrest and murder of leaders in the Jewish community. As the ground shifted under their feet, Persian Jews desperately sought avenues of escape, especially for their children.

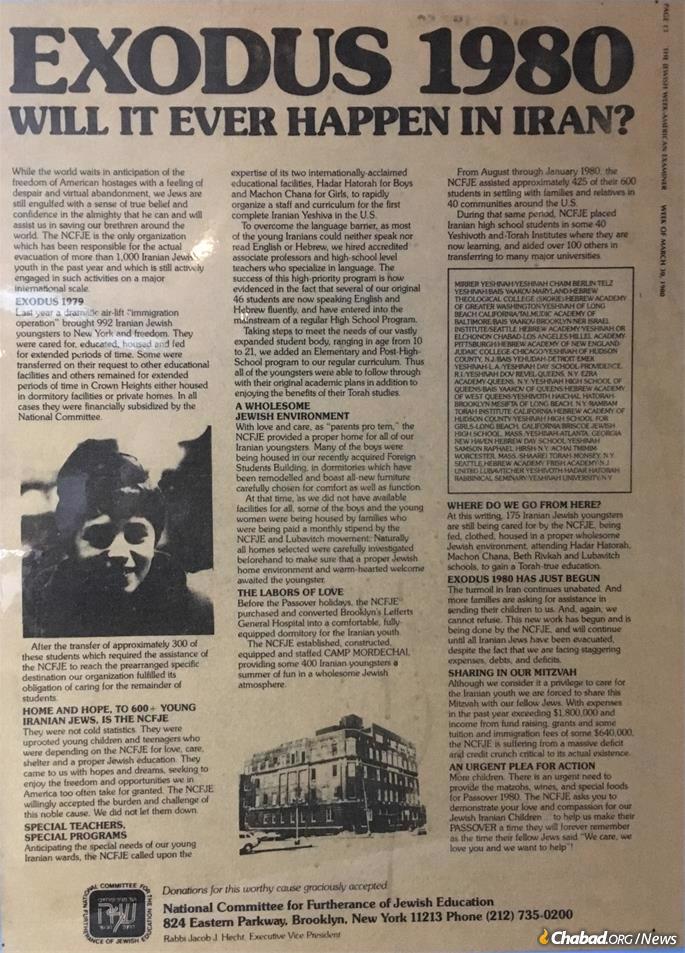

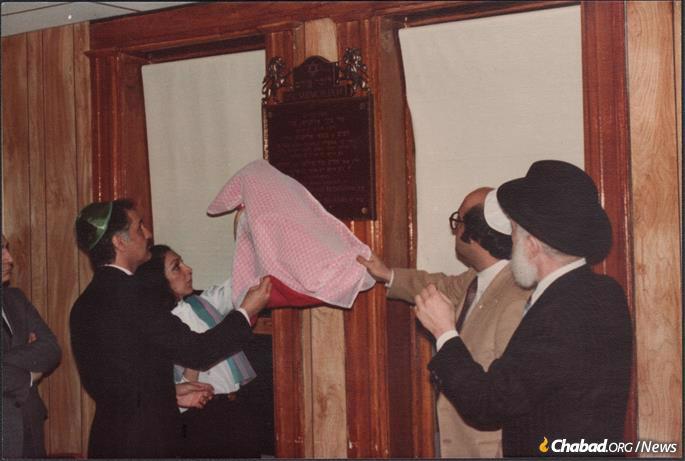

The answer came in the form of Operation Exodus, a historic Chabad-Lubavitch effort, still largely unknown, to rescue the Jewish children of Iran. With help from the Crown Heights community and an army of volunteers, the operation was spearheaded by the late Rabbi Yaakov Yehudah (J.J.) Hecht, the exuberant executive vice president of the National Committee for the Furtherance of Jewish Education (NCFJE), and personally approved and encouraged every step of the way by the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. Operation Exodus was by far the largest organized effort to rescue the embattled Jews of Iran, and by the time it wrapped up in 1981 had brought 1,800 children to the United States. While Hecht was promised financial assistance from mainstream Jewish organizations, much of it never materialized, leaving him to cover the expenses alone. When Hecht passed away a decade later, his organization was still millions of dollars in debt. Yet he never for a second regretted it; there were Jewish children to be rescued, and he had gotten it done.

‘Very Similar to Our World in Iran’

Anna Monahemi, today State Sen. Anna Kaplan, was elected this past November to the New York State Senate from North Hempstead. The first streets of America that she wandered were those of Chassidic Crown Heights, and she recalls being taken by the pre-Shabbat shopping rush along the main commercial thoroughfare, Kingston Avenue, and hearing the Rebbe speak at the central Chabad synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway. She still remembers the address on Montgomery Street where she stayed with a handful of other girls, the Chassidic family having taken a basement bedroom used by their own children and repurposing it for the girls.

That Passover she joined hundreds of other Iranian girls at one of the communal seders organized for them, where, along with Farsi Haggadahs, they were served rice as per the Sephardic custom.

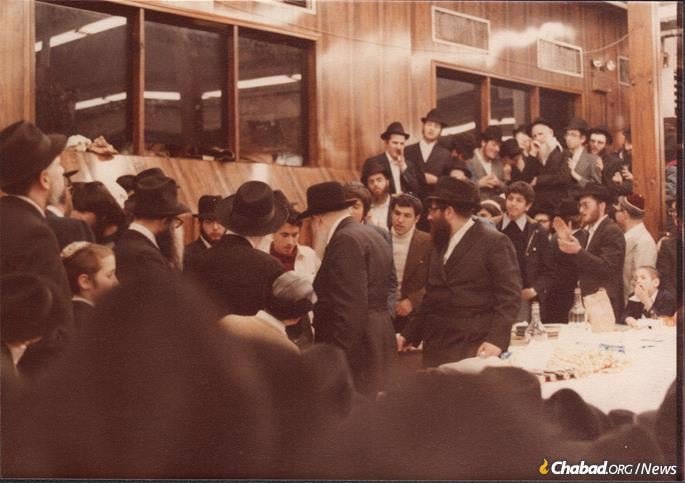

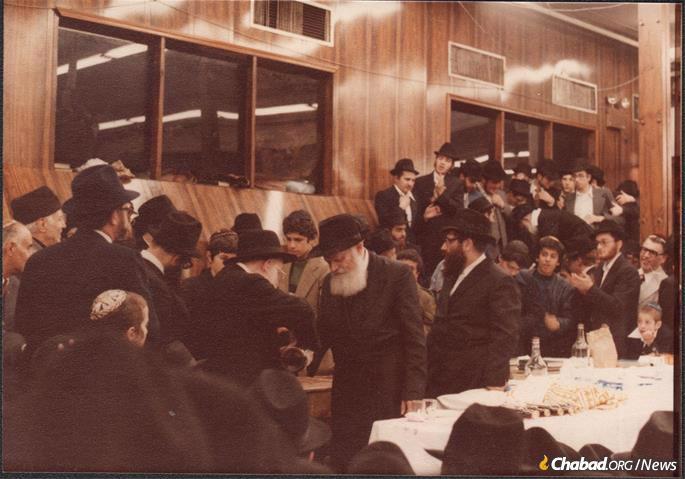

In fact, it had been the Rebbe who insisted that every effort be made to make sure the Iranian children were as comfortable with their new surroundings as possible, including serving them rice, which is considered kitniyot and not consumed by Ashkenazi Jewry on Passover. The Rebbe personally visited the Iranian childrens’ seders, held in multiple locations, stopping first in the kitchen to thank the staff, where he saw the rice being prepared. In the dining rooms he addressed the children in Hebrew, waiting as one of the children translated his words into Farsi.

Kaplan remained in Crown Heights for the next few months, spending the summer at NCFJE’s Camp Emunah in Upstate New York before joining one of her older brothers in Chicago. Another brother of hers followed a similar route as she, going from Tehran to Crown Heights before moving on to Chicago as well.

Kaplan says that for her, the differences in culture between the traditional, though not observant, home she came from in Tehran and the world of Chassidic Crown Heights were not all that different.

“My goal was continuing my studies and getting an education, which included Jewish classes I took there,” Kaplan tells Chabad.org. “But the Lubavitcher community’s emphasis on family and the family unit, it was very similar to our world in Iran.”

To her, the moral of the story is simple: “Human beings try to help each other when someone needs help. The Rebbe was instrumental in that.”

The decision to send her and her brother out of Iran had been a difficult one for her parents, but they felt a sense of urgency to get them out of the country. This was made easier, however, by the fact that they were being taken in by fellow Jews. “That fact gave them comfort.”

Ultimately, it is the kindness of her hosts that has remained with her, as well as the opportunities she received as a result.

“They opened their home to us, and I’ll always be grateful for that,” she says. “Today, I’m living the American dream. I came as a political refugee and was now elected to a high office in a great state in the greatest country on earth.”

Kaplan spoke to Chabad.org on a winter afternoon one Friday. “After this call, I’m going to prepare for Shabbat,” she said. “My mother is joining us.”

Accidental Beginning

This unlikely story of rescue began in the late 1970s, when an Italian-born Chabad yeshivah student named Hertzel Illulian was studying in New York. His parents were successful Persian Jewish immigrants, traditional but not religious, and he had grown up in comfort in Milan. After serendipitously meeting a Chabad Chassid on the streets of Milan, who helped him don tefillin for the first time, Illulian became more religious and eventually came to New York to study at the Lubavitcher yeshivah.

Like his fellow Chabad yeshivah students, each summer he’d enlist in the Merkos Shlichus rabbinical visitation program to share, teach and strengthen Judaism in underserved and remote Jewish localities. Illulian dreamed of traveling to his ancestral homeland, Iran, to try to impact its Jews as he had once been influenced in Milan. Iran was safe, he spoke Farsi; it was a good match. In 1976, he wrote to the Rebbe requesting a blessing for a summer posting to Iran, but received no reply. The same thing happened the next summer.

Then came the summer of 1978. Illulian had an uncle in Forest Hills, Queens, whom he often visited and who prayed at the Sephardic Jewish Congregation, led then as it is now by Rabbi Sholem Ber Hecht, Rabbi J.J. Hecht’s eldest son. It was to Hecht that Illulian broached the idea of going together on Merkos Shlichus to Iran.

Hecht was intrigued. From what he heard from his congregants—a mixture of Sephardic Jews, Persians included—Iran might benefit from such a visit. Illulian again wrote to the Rebbe, and this time got a positive response. The details were then worked out, and both Illulian and Hecht raised the funds needed to cover the trip.

“Our original intention was to establish a liaison with the community there, and then see if it made sense to send an official emissary there,” says Hecht.

Illulian went about translating some Jewish beginner texts into Farsi, as well as the 12 Torah passages (pesukim), specially chosen by the Rebbe as verses children should learn and know. He also packed a few suitcases with mitzvah lapel buttons, Chassidic records and mezuzahs—and off they went.

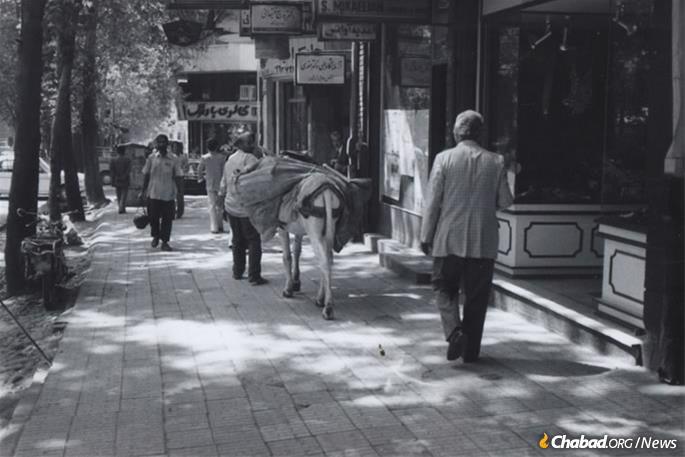

They landed in Tehran on a calm day in August of 1978. Revolution, refugees ... that was the last thing on their minds.

Tehran, 1978

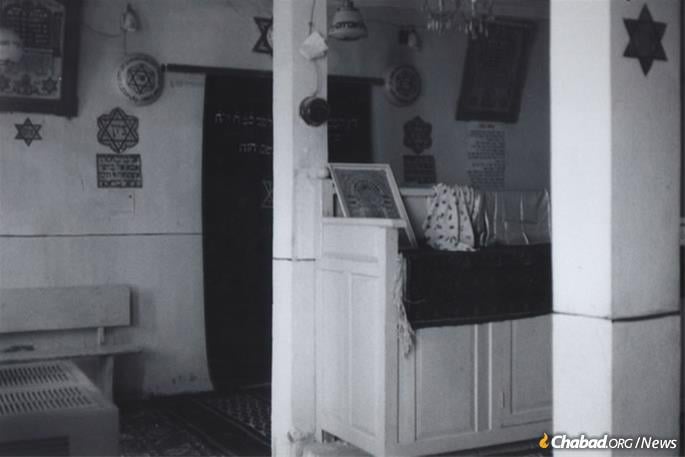

The Iran the two young rabbis found was a rapidly Westernizing one, and the Jewish community, while traditional, was largely affluent and modernizing. Hecht and Illulian were officially greeted by Rabbi David Shofet, son of Iran’s chief rabbi, Chacham Yedidia Shofet, and himself at the time head of the Jewish community umbrella organization; Chacham Netanel Ben-Haim, who headed the Ozar Hatorah religious school system; and Rabbi Eliyahu Ben-Haim, who led both the Yusef Abad and Meshadi synagogues in Tehran.

Arrangements were made for the pair to address on Shabbat the five or so main synagogues in Tehran, which on a weekly basis could draw anywhere from 500 to 1,500 people.

“A lot of people thought we were there to collect money,” remembers Hecht. Many Jews, but not all, lived in opulent homes, drove Cadillac Sevilles or Mercedes 500s, and were accustomed to foreign rabbis coming to collect funds. “The first thing we did was get up and say, ‘We didn’t come to take; we came to give.’ That surprised them. We told them we were there because the Lubavitcher Rebbe has sent us there, we spoke about Judaism, encouraged them in their practice. We were very respectfully received.”

For many centuries the Jews of Persia, like those in other Muslim-majority societies, were dhimmi, a tolerated but second-class-status minority. In modern Iran under the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, this had changed. He instituted a series of reforms, including breaking down the barriers that had been placed upon the Jews. This proved to be a good investment for the regime, as the Jews flourished economically, contributing handsomely to the new Iran, repaying the Shah with their loyalty as well. On the other hand, similar to what happens in other upwardly mobile societies, this had a negative impact upon the religious standards of the Persian Jewish community at large. Laxities crept in. Whereas the Ozar Hatorah schools, established in Iran in the aftermath of World War II, had once had thousands of Jewish students all over the country, by the time Hecht and Illulian visited, the branch in Tehran had perhaps a few hundred children enrolled.

Bension Kohen had studied at Ozar Hatorah’s elementary school and graduated from the ORT high school in Tehran. When the two Chabad rabbis visited, Kohen was studying in a university and working part-time as an electrician at the Royal Gardens Hotel, where the pair stayed.

“I met them and volunteered to be their chauffeur,” says Kohen. “You see two Jewish guys with beards and a kipah, you get excited. I introduced myself and stayed with them for the next couple of weeks.”

While Hecht and Illulian had come to what was still a stable Iran, street demonstrations against the Shah had already begun. The Shah, while liberal in many ways, ran a police state, and his human-rights record did not match his economic reforms. People were agitating for more basic freedoms, but it was not obviously being fueled by Islamists. “[T]he revolution … at first appeared to be a broad-based coalition embracing the merchants, students, and many moderate elements, in addition to the reactionary clerics,” writes the late foreign-policy expert Peter W. Rodman. “[O]nly gradually did it become clear that, as in Petrograd in 1917, vacuums are often filled by the most ruthless, the most disciplined, the most fanatical.”

Hecht recalls sitting in the home of Chacham Ben-Haim following Shabbat and seeing the television screen flashing images of street demonstrations turned violent. “That’s why we didn’t go to any other cities outside of Tehran,” he says. “We were afraid to get caught up.”

The sudden violence frightened the Jewish community. Whereas the Chabad rabbis had hoped perhaps to meet a handful of Jewish boys who would be interested in coming to America to study in yeshivah, by the second week of their trip Iranian parents began approaching them about the possibility of sending their children with them. The trip was set to last one month, with Hecht, who was married and had children, returning home after two weeks, and the late Rabbi Yossi Raichik, then a yeshivah student, joining Illulian for the second segment of the trip. By the time Hecht left, 20 sets of parents had inquired about sending their children to America.

Hecht also gave his phone number to Kohen, their young driver. “He told me, if you come to America, here is my number,” recalls Kohen. A few months later, that number would come in handy.

Meanwhile, Raichik arrived to join Illulian. He carried plates from which they printed a special Iranian edition of the Tanya, the central text of the Chabad movement, penned by its founder, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi. But the circumstances on the ground were getting worse. Illulian was in regular contact with the Rebbe’s chief of staff, Rabbi Chaim Aizik Mordechai Hodakov, who counseled him to stay safe.

Illulian had a close call with the Shah’s secret police. One afternoon he found himself in a car close to Tehran’s InterContinental Hotel, and the window for praying the afternoon minchah service closing. He stopped, pulled out a prayerbook and began reciting the words as he swayed.

“Suddenly, I got surrounded by a lot of strange people,” Illulian recalls in an interview with Jewish Educational Media’s (JEM) My Encounter with the Rebbe oral history project. “They thought I was a terrorist … and wanted to arrest me.”

Illulian’s Jewish driver tried to intercede, telling the agents that Illulian was harmless. The authorities left Illulian but detained the driver.

By that time, “they were burning things in the streets, destroying pictures of the Shah and government property,” remembers Kohen.

Instability or revolution almost always places the Jewish community in particular danger, but the Islamist element of this one was far more open from the outset about their antagonism. While Iran’s Jews had lived in relative safety, even prior to these events Iran was not a place by any stretch that was free of anti-Semitism. But now, the threats were becoming explicit.

“Warning to all the Jews of Iran,” read a June 1978 flyer signed by a group calling itself the National Front of Young Muslims in Iran and forwarded by cable from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran to the State Department in Washington. “You blood-sucking people who have gathered in our Islamic country and are bleeding every one of us Muslims by extorting money-lending interest, theft and swindling and sending the wealth collected in this way to the Zionist country of Israel … be aware now that your golden days are over. … You are hereby warned to leave the country as soon as you can otherwise we will massacre all Jews. … A Hitler is a necessity once in a while to exterminate the Jews … ”

Now Illulian and Raichik found themselves inundated with requests from parents asking them to take their children with them. Illulian called Hecht and explained the unraveling situation. Rabbi Sholem Ber Hecht turned to his father asking what they could do. Was it their job to now begin ferrying Persian Jewish children to the United States?

J.J. Hecht was a legendary personality. Loud, energetic, dedicated, he had the voice of an old-time orator, hosted a regular Jewish radio program on New York’s WEVD and ran a whirlwind of projects through his organization, NCFJE. He was also fiercely loyal to the Rebbe, and in foot-soldier fashion would write reports and queries regarding his work to the Rebbe multiple times a day. There was even a joke that went around that he needed to hire a full-time courier to bring his messages down the block from his office at 824-828 Eastern Parkway to the Rebbe’s secretariat at 770.

In this case, too, the elder Hecht turned to the Rebbe to ask whether this was a project he should now take on. Even a modest number of children would require I-20 student visas and all the paperwork that entailed, plus food, housing, schooling and more. The response was an unequivocal yes. The Rebbe said that this project would be a blessing for both the Iranian Jewish community, and for Hecht and his organization.

“That’s what the Rebbe said, so that was it,” says his son. “He undertook the whole task.”

Did he have any idea what this would entail?

“I don’t think he did,” replies Rabbi J.J. Hecht’s wife, Rebbetzin Chava Hecht. “That’s how he was. He jumped in, even if the water was freezing.”

A Trickle Turns Into a Flood

In October of 1978, during the intermediary days of the holiday of Sukkot, Illulian returned to Tehran alone, this time armed with I-20 visa applications issued by Hadar Hatorah, the first-ever yeshivah for young men returning to the traditions of their ancestors, run under the auspices of NCFJE.

“Herzel had the list of names of students who had decided they actually wanted to come, so we were able to start issuing I-20s for them,” says Hecht. “So we started doing that, then we had to also send all the supporting documents, which also had to be signed, including source of income, etc. So my father decided to sign those also.”

Aside from the street demonstrations, the Shah, struggling to squelch the unrest in his empire, began drafting young men not in university into his military. Another option that was given was to show proof of acceptance to a foreign university, so the young person would quickly be granted an exit visa. This was another reason for parents to find a way out for their children.

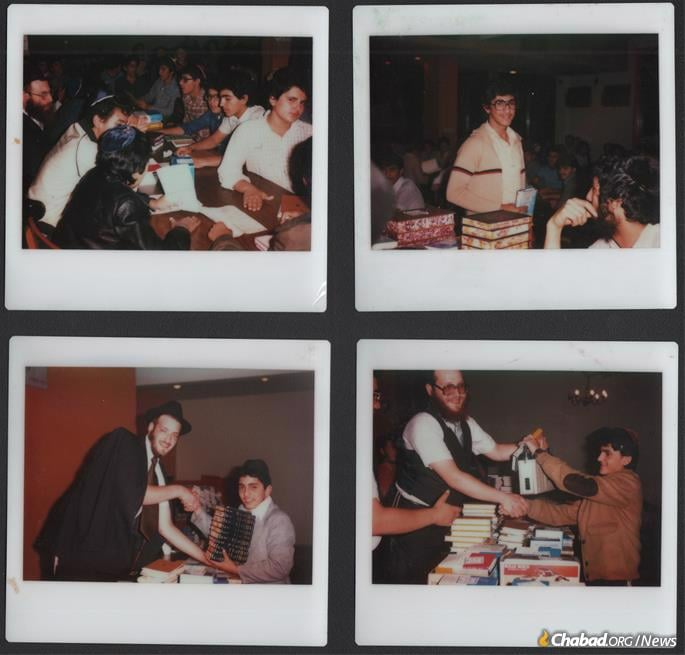

Despite the growing tensions, the American embassy in Tehran was still properly staffed at the time, and Illulian was able to file the paperwork at the embassy, which issued the visas. A few weeks later, Illulian returned together with the first group of Iranian Jewish children, about 40 students. The boys were enrolled in Hadar Hatorah, while the girls attended Beth Rivkah, the flagship Chabad school for girls. There was plenty of dorm space for the boys, and the girls were put up with host families.

“The word got out in Iran that this is the way to get your kids out of trouble,” says Hecht. “All of a sudden, we started getting calls from Rabbi David Shofet; he heard from mothers that they needed hundreds of these visas. So from November, December, January ... those months, we started sending them huge numbers of I-20 applications.”

As the situation grew worse, the Shah received mixed messages from Washington. The State Department, on the one hand, led by Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, was of the opinion that in order for Iran to stabilize and move in a more liberal direction, the Shah had to leave. President Jimmy Carter’s national security staff, on the other, led by Zbigniew Brzezinski, felt that the Shah was a stabilizing presence and a vital ally in the region who should be supported in his time of trouble. While it was true that the Shah was a dictator, the alternative, Brzezinski and others felt, would spell disaster. Carter leaned towards Brzezinski’s view, but this wasn’t being clearly communicated to the Shah, especially by the American ambassador to Iran, William Sullivan.

The Shah vacillated, unwilling or unable to pull the trigger and order the military to harshly crack down on the revolution in his streets. On Jan. 16, 1979, the once-all-powerful monarch of the Imperial State of Iran boarded an airplane and left the country for the last time.

Bension Kohen left Iran the next day. He had purchased an acceptance form to Queens College on the streets and arrived in New York before Shabbat. On Sunday he dialed Hecht, who told him to stay where he was and he’d pick him up. The Farsi-speaking young man, who soon found himself volunteering as a counselor and cook in NCFJE’s booming Persian children’s program, has lived in Crown Heights ever since.

Two weeks after the Shah’s departure, the exiled Khomeini made his triumphant return to Iran. The Islamic revolution in full force, there was no turning back.

Murder and Panic in the Streets

The mood in the Iranian Jewish community was tense. While worried, they remained deeply tied to the country. They had homes, properties, businesses, investments; it had been their native land for millennia.

“People had this idea that this had happened once [the attempted coup against the Shah in 1953], and the Shah could still return,” explains Rabbi Shofet, who played a central role leading the teetering Jewish community in Tehran during those heady days, and is today the chief rabbi of the Nessah Synagogue and Center in Beverly Hills, Calif. “It was an illusion.”

And so Shofet encouraged parents to send their children out via Chabad.

“When there’s trouble, people turn to G‑d,” says Dovid Loloyan, by now also a rabbi in California, but at the time a 12-year-old boy growing up in a non-religious Persian Jewish household in Tehran. “My mother started going to synagogue, and there, in Rabbi Shofet’s shul, she heard him saying that there’s this group, Chabad, taking children to the United States to study, and we’d be able to go to college, too, because with Iranians there’s no way their child isn’t going to college.”

Loloyan’s mother at first wanted to send her son to join his sister in Israel, but in Feb. 1979, El Al, fearing for the safety of its staff, suspended all flights to Tehran. That’s when she heard Shofet’s pronouncement in the synagogue, and the decision was made to send him to America.

Loloyan was 12 at the time, and had seen protesters burning banks and looting stores, soldiers mowing down protesters. He wanted to leave, and the family went about quietly preparing.

“It was known among the Jews that we children were leaving,” says Loloyan, “but we kept it secret from the Muslims.”

Loloyan was a part of one of the first groups to leave Iran after the actual revolution—150 children in all. By this time the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, which had been briefly overrun by Islamist militants in February before being freed a few hours later, had pulled back much of their staff, with the ambassador, Sullivan, being recalled in March. The I-20s could no longer be processed in Tehran. A third country was needed, and with Illulian hailing from Italy and a Chabad emissary, Rabbi Yitzchak Hazan, stationed in Rome, the decision was made to route the children through there.

Loloyan’s group landed in Rome on March 13, 1979, coincidentally, on the holiday of Purim, which commemorates the deliverance of the Jewish people in ancient Persia approximately 2,400 years ago. In Rome, the children were promptly led to a reading of the Megillah, the Scroll of Esther retelling the story. It was the first time Loloyan ever heard it.

Miriam Finck has a similar story. In fact, her brother had nearly been a victim of the street violence. Among the enduring slogans of the Islamic Revolution were the chants “Death to America!” and “Death to Israel!” Two years her senior, Finck’s brother had seen a “Death to Israel!” placard hanging on the street and tried pulling it down. He was caught and taken to a university to be hanged. It was only through the immediate intervention of her uncle—Finck’s father had recently passed away—who ran to an influential Muslim acquaintance and begged him to intercede on his nephew’s behalf that the boy was spared.

“That’s when my family knew it was over,” she says.

It was her uncle, too, who had heard a rabbi speaking in his synagogue of a way to send their children out. He told Finck’s mother about it; within three days, she and her sister had passports.

The two girls and their group headed to Rome in March of ’79 as well. When they were leaving, Finck remembers giving her coached response to Iranian authorities, that she was going to Rome to visit relatives.

In April of 1979 Khomeini announced the formal establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. But in May came the greatest blow to the community: the execution of Habib Elghanian, a wealthy and respected leader of the Iranian Jewish community.

“The execution of Habib Elghanian last week created a great sense of anxiety within the Iranian Jewish community … ,” reads another U.S. embassy cable. “A general feeling was that, if a person of Elghanian’s stature was not safe, then all Jews were in jeopardy.”

In Rome, Loloyan, Finck and her sister, Anna Kaplan and her brother, and the hundreds of other children, were greeted by Illulian, who was stationed there for a period of months. While Loloyan was in Rome for three days, Finck recalls staying there for two weeks in a nursing home, waiting to be processed at the American Embassy in Rome.

“I was going to the American Embassy in Rome and they were so nice, so helpful, G‑d bless this country, how much kindness, how much heart they have … .” Illulian told JEM in his interview. “I became like a worker in the American Embassy. I was going in and out like a consul, with three, four hundred passports of these little kids that I gathered.”

He would gather hundreds of children at a time at an embassy facility and in Farsi direct them in filling out the visa applications. A few hours later the visas were stamped, nearly pro forma, and the children ready to board airplanes to America.

“I was in Rome for a few months until every child came to America,” Illulian recalls. “I’d go to the airport, place them, go to the embassy and get the visas, and then send them to America. There was an unbelievable energy. I would speak to the children about what was going on, about Judaism, about mitzvot; we would spend Shabbat together. But there were many nights when I did not sleep more than an hour or two.

“The way we were getting these visas at the embassy,” Illulian adds, noting that there were thousands of other refugees in Rome working to get American visas, “it was a miracle.”

Not everyone believed Khomeini was all that bad or that the Jews were really endangered. Yet another U.S. embassy cable from Tehran, this one signed by Sullivan in March of 1979, states that although Jews were certainly the subject of prejudice in Iran in the new climate, they were no worse than any other minority and “appear to have reached a reasonably satisfactory accommodation with the new powers that be.” Sullivan concludes that the general “shift does not, in our view, represent a change that would warrant treating Iranian visa applicants, whether members of minority groups or not, any differently than we have in the past.” While the Iranian children in Operation Exodus were processed as students and not refugees, the speed at which it was done indicates that this advice was ignored.

From Rome, the groups headed in biweekly and then weekly waves to JFK airport, where they boarded buses to Crown Heights. Between November of 1978 and April of 1979, 1,000 children came to New York in this way.

In Rome, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) assisted greatly with the processing, but all of the other responsibilities—financial and logistical—lay with the Chabad movement and Rabbi J.J. Hecht.

The Hub: Crown Heights

In the beginning, things were simple enough. Most of the boys stayed in dormitories, while some of the younger boys and all of the girls were placed with hundreds of host families. Like Kaplan, Finck and her sister were placed with a family—with whom she remains close to this day—as was Loloyan.

“I used to visit families hosting the children every week,” says Moshe Chayempour, an Iranian Jew who had arrived in America in 1970 and was instrumental in Operation Exodus from the get-go. “These were not wealthy people hosting the children, but they took their own children’s bedrooms and gave them to these children. Who does that? It was unbelievable.”

Roslyn Malamud and her husband were one of the families that took in children; two boys stayed in her home for more than a year. Today, the boys are active Jewish community members in heavily Persian community of Great Neck on Long Island, N.Y., and Malamud remains in touch with them, attending their weddings and, more recently, their children’s weddings. Her biggest motivation for taking in the children was her mother, who was born in Poland and had come to the United States before the war, but had lost much of her family in the Holocaust.

“My mother said, if before the war more people had taken in Jewish children, more children could have been saved,” says Malamud. “No one knew what was going to happen to the Jews over there, but this situation, it hit home.”

Malamud ultimately got involved in more ways, even later traveling with a group of involved Chabad women and the senior Rabbi Hecht to Washington to lobby members of Congress for more student visas for the Iranian children.

Hecht, responsible for the entire operation, was also not above hosting. He and his wife had two girls, Janet Afrah, then 14, and her sister Jackie, then 11, live in their home for months.

“I had no children at home, so I was able to give them my full attention,” says Rebbetzin Hecht.

The Hechts lived in nearby East Flatbush, where Rabbi J.J. Hecht was rabbi of a synagogue, so the solution was supposed to be temporary, as Rebbetzin Hecht didn’t want the girls to feel alienated from the other Persian girls.

“But we gravitated towards each other,” says Afrah, “so we just stayed.”

The connection would end up being a lifelong one. Towards the end of 1979 the girls’ parents managed to make it out of Iran and moved to Atlanta, with their daughters joining them soon thereafter. When Janet got married, Rabbi and Rebbetzin Hecht flew to her wedding in Atlanta where Rabbi Hecht presided over her chuppah; this repeated itself when her younger sister married some time later.

“Two years ago my son got married and Rebbetzin Hecht came with her son, who read the Rebbe’s letter of blessing for the wedding, the one he sent when I got married,” says Afrah. “Rebbetzin Hecht sat at the badeken [the ceremonial veiling], together with my mother. I have always said I have two sets of parents.”

For her part, Rebbetzin Hecht found herself overcome with emotion: “I cried,” she says.

But back in 1979, as more and more children came, there were problems that arose, especially in housing the older boys.

“Desperate for homes and beds for the children, who range in age from 10 to 22, Rabbi Jacob J. Hecht … signed a $500,000 contract on Monday [April 9, 1979] to buy Lefferts General Hospital,” reported The New York Times in an article titled “Jews in Crown Heights Make Room for Iranian Children.” The article notes that the building was in shambles, but excludes the fact that Hecht had signed the contract with the doctors with assurances that it was habitable, which it was not.

While desperate times call for desperate measures, the fact was that despite the revolution, many of the children did not regard themselves as refugees. The Times article even quotes a 17-year-old Iranian boy named Israel explaining that “[m]any people think we escaped from Iran. I personally came from Iran because I wanted to read and study Jewish studies … I didn’t want to escape Iran because of the political situation.”

“Some of the children, especially who came from rich families, they didn’t understand they were refugees and they complained. When a guy is used to his parents’ villa and leather couches in Tehran and then is dumped on a yeshivah mattress in Brooklyn, they don’t appreciate it,” says Kohen. “Their parents were scared and sent them away, but the children didn’t always want to understand that the situation back home was so bad that there’s no way to live there anymore.”

“Everyone thought we just need a couple of months, things will calm down and we’ll return,” recalls Afrah. “That was 40 years ago and we never went back.”

While mainstream Jewish philanthropic organizations promised (and raised) funds for the effort, Rabbi Hecht received only token amounts, struggling to cover his ballooning budget. Instead of money, he got explanations that the Iranian Jews were wealthy and could pay their own way. That meant that not only was NCFJE and Lubavitch alone in the work—a few other Orthodox Jewish organizations brought over children on a far smaller scale; mainstream organizations did not—Hecht was footing the bill.

“It was very hard; it was a lot of money and worry,” admits Rebbetzin Hecht.

The expenditures were not limited to the hospital. Hecht also obtained campgrounds in Monticello and Far Rockaway for summer camps for the Iranian children, aptly named Camp Mordechai for the hero of the Purim story, and established a new school with Farsi-speaking teachers, ESL classes and the like in Crown Heights. The costs soared, but he did it anyway.

“My husband’s approach was: The Rebbe told you to do it, you do it. You don’t do it for the thank you, you do it to do it,” says Rebbetzin Hecht. “My husband didn’t need a thank you; he wasn’t the type.”

The Hostage Crisis

Passover 1979 was meant to be the last hurrah for Operation Exodus. “As far as I know, I am now stopping,” Hecht told the Times. But he didn’t.

For one thing, things got even worse in Iran. As tensions between Iran and Iraq intensified, the new Islamic republic began snapping military-age boys off the streets to send them to what would turn into the devastating Iran-Iraq War. From the beginning there were also valid worries that the girls could be grabbed and raped on the simmering streets. But by late 1979, Rome had become overrun with other asylum seekers, and, as Chayempour recalls it, the Rebbe suggested London as an alternate center where the Jewish students could be processed.

Then came the Iran hostage crisis on Nov. 4, 1979. Islamists overran the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took its staff hostage for 444 days. The U.S. severed relations with Iran, an embargo on Iran was put in place, and the United States stopped issuing student visas.

“Since there were no forthcoming American visas, Britain wasn’t prepared to issue even temporary visas for the Iranian children,” explains Rabbi Faivish Vogel, a leading Chabad figure in London. “I was asked to solve this problem and get visas for these children.”

Vogel phoned a Jewish member of parliament, Greville Janner, and told him there were 200 Iranian Jewish children who needed to get to London. He asked Janner, a member of the Labour Party, to approach the Home Secretary William Whitelaw, a Conservative, and request visas for the children.

“Whitelaw asked him: Who will guarantee that they will leave Britain?” recalls Vogel, “and Janner told him: Rabbi Vogel of the Lubavitch Foundation.”

Chayempour and Raichik flew to London to make arrangements for the children, whose presence in London was kept quiet. The children arrived in groups; Chayempour recalls heading to Heathrow to help take the children off the plane and past immigration. In at least one case, the plane made a stopover in London on its way to a third destination, and Chayempour was ushered onto the plane to collect the children, who were transferred onto Chabad-sponsored buses while Chayempour had their passports validated and visas inserted.

A portion of the boys were sent to Carmel College, a since-closed elite Jewish boarding school in Wallingford, Oxfordshire, and Raichik went there to serve as their counselor. Another portion of the boys was enrolled at the Hasmonean School in London while the girls were enrolled at the Lubavitch Senior Girls School in Stamford Hill, London. But as the months stretched by, the American visas were still not forthcoming.

Meanwhile, Rabbi Avraham Shemtov, the director of American Friends of Lubavitch in Washington, worked his connections in the Carter administration and Congress.

“Rabbi Shemtov worked very hard to get the green signal from United States that the embassy in London should give visas to these kids,” Chayempour told JEM in an interview. “We waited many months until, thank G‑d, on the day after Tisha B’Av, we got a call from him that we are approved and the kids can go.”

With the full participation of the American Embassy in London, the I-20 student visas were granted to the Iranian children—unusual given official U.S. policy at the time—and the children finally flew to New York.

With that, Operation Exodus came to a close, having saved 1,800 Jewish children from the clutches of an untested radical regime.

In the coming years, 80,000 Jews left Iran, many of them having to smuggle themselves out illegally. The children—Loloyan, Kaplan, Finck, hundreds of others—were only reunited with their parents years later, and Rabbi Sholem Ber Hecht remembers signing hundreds of letters of support for Persian families attesting to their refugee status and the persecution in Iran, allowing countless more Iranian Jews to finally leave.

‘An Entire World’

Throughout Operation Exodus the senior Rabbi Hecht corresponded on a daily basis with the Rebbe, whose guidance was crucial to the operation’s success. NCFJE’s archives hold hundreds of letters written by Hecht to the Rebbe and replies on every minute detail of the plans. One letter from Hecht requests the Rebbe’s blessing for a group of 70 Jews who had been ferried by another organization via an illegal crossing on the Pakistani border and had been caught:

… It was done illegally, cost immense sums of money, and we did not want to be mixed up in this because we suspected that the organizers are unscrupulous people … G‑d Almighty should have mercy that they should be saved in a miraculous way.

Yaakov Yehudah the son of Sarah, Hecht

*They are in need of great, unbounding and intense mercy.

The Rebbe’s response in this case is unclear, but the Rebbe made a special point to constantly engage and encourage the Iranian children coming through Crown Heights. On Purim of 1979, the Rebbe famously had the Persian children seated together in a place of prominence at his gathering and requested that they sing a Jewish song familiar to them. They began singing the Sephardic tune of “Yigdal Elokim Chai,” and the Rebbe motioned for the thousands of Chassidim gathered to join along.

On the last day of Passover that same year, the Rebbe spoke one of many talks on the subject of the Iranian children, requesting at the end that it be translated into Farsi for their benefit. He spoke of the revolution in Iran, the hidden blessings that it contained, and the new hope for the children who had been exiled from their homes. He pointed out that many of the Iranian children had joined along in the taahalucha—the Chabad tradition of walking to other synagogues to share words of Torah and the joy of the holiday with fellow Jews from all walks of life—and had brought happiness and song to local American Jews, while they had only just themselves arrived.

The organizers of Operation Exodus, the Rebbe said, “should not fear that they have wasted so much energy on such a [relatively] small number of children, for every individual is ‘an entire world,’ and they will go on to impact their entire family and their whole environment.”

Forty years later, the Rebbe’s words still ring true. The Persian Jewish community in the United States is blooming, proud of its roots and fiercely connected to its Jewish heritage.

“The Rebbe told my husband that if even 10 percent of the Iranian children remain connected to their Judaism, then the effort was all worth it,” says Rebbetzin Hecht. “The numbers are far, far higher. We really saw the payoff.”

“The Rebbe saw what was happening and acted upon it and saved a lot of people, not only physically but spiritually as well,” says Afrah. “How many people were saved? A lot. I started off as one person and now have five children and six grandchildren. There were 1,800 children, and we are three generations already, and it will, G‑d willing, continue.”

Join the Discussion