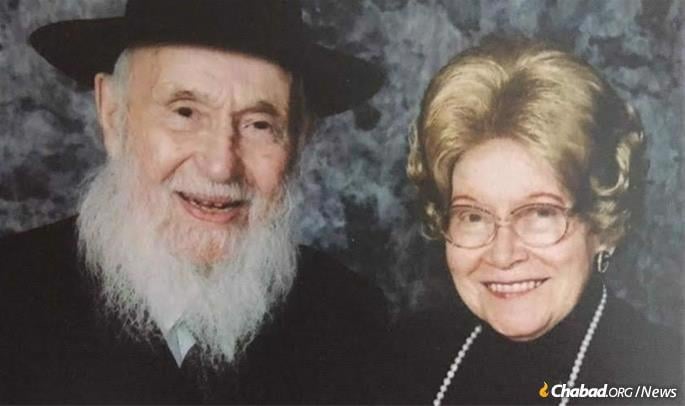

Revered for her fiery personality and rock-solid faith forged during a childhood in the former Soviet Union, Rebbetzin Shula Shifra Kazen nourished, guided and inspired thousands during decades of communal leadership in Cleveland, Ohio. She passed away on March 24 in New York at the age of 96.

She was born in 1922 in Gomel, Belarus, then part of the newly-created Soviet Union.1 The eldest of seven children born to Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan and Maryasha (Garelik) Shagalov, her life began in difficult circumstances. Russia had been devastated by the terrible civil war that birthed the Bolshevik revolution, and thousands were dying of starvation.

When the family dreamed of bread, Maryasha Shagalov told Shula to recite Psalms with concentration, and the day would come when they would have more than enough food. Shula prized saying Psalms, something that would sustain and encourage her for the rest of her long life.

By law, all children were required to attend public school, where Communist ideals were taught. Determined to raise their family according to Jewish law and tradition, the Shagalovs refused to send their children to the public schools. Eventually, the large family became known to the government, which revoked their rations of food and fuel, and even had them evicted from their home onto the frozen streets.

The Shagalovs moved into the local synagogue, where Elchanan continued battling for Jewish life, which included serving as mohel (circumcisor). He was often accompanied by Shula, who assisted him in his sacred (and illegal) task.

In 1937, he was arrested for illegal activities in support of Judaism for the last time. Years later it was learned that he was executed three months after his arrest, but his widow and orphans were left wondering about his fate for decades.

Facing an unrelenting barrage of pressure from the Communist government, Maryasha had no choice but to send her children into hiding. As the eldest, 14-year-old Shula took a 12-hour trip to the home of Rabbi Bentzion (Bentche) and Esther Golda Shemtov, pillars of the underground Chabad-Lubavitch network of Jewish life.

The Shemtovs sent her to Moscow, where she found work in a knitting factory that Bentzion Shemtov had arranged. It was one of the few places where people could find legal employment that did not require them to work on Shabbat.

Her job was to carry hundred-pound bags of material on her back from the supplier to the factory. After the material was made into scarves or other headgear, Shula would carry it to the buyer, who would pay her. Shula helped support her mother and younger siblings with her earnings.

Shortly after she turned 18, Shula was introduced to her future husband, Zalman Katzenelenbogen (later shortened to Kazen). Like her, he had also lost his father to the Communists in the dreadful purge of the fall of 1937.

Shula did not have a single decent outfit in which to meet her future husband. One friend loaned her stockings, another a shawl, a third one a coat, and somehow she was able to obtain boots. The only clothing she owned was a dress and a coat that “grew” with her. She received the coat at age ten, refitted it countless times, and wore it up to her wedding. For her wedding, a friend sewed her a white dress made of inexpensive fabric.

The wedding was held on 12 Elul, 1940, in a forest at the edge of Malachovka, outside of Moscow. Any religious ceremony was punishable by imprisonment or death, including a traditional Jewish wedding, so it had to take place in complete secrecy. After their wedding, Shula and Zalman Kazen settled in Leningrad.

Fleeing to the West

As the Nazis advanced toward Leningrad in the fall of 1941, Shula convinced her husband and many other families to flee. Those who left had a chance at survival, but many who remained died of starvation during the Nazi siege of the city.

The Kazens traveled in an open cargo train for a month until they reached Tashkent, Uzbekistan, more than 4,000 kilometers southwest of Leningrad. Shula was pregnant with her oldest child and was grateful that she and the baby survived. Shortly after reaching Tashkent, they had to escape from the watchful eyes of the KGB and fled further south to Samarkand.

As soon as the war ended in 1945, Shula insisted that the family must escape Russia. By that time they had three daughters, Esther, Dvonya (Devorah), and Henya. The family traveled from Samarkand to Moscow, and from there to Lviv, where they crossed the border into Poland using black-market Polish passports. Shula’s mother-in-law, Mumme Sarah Katzenelenbogen, was one of the stalwarts of the underground operation.

Mumme Sarah had Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, the mother of the future seventh Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—join the family as their “grandmother.” Mumme Sarah was arrested by the Communists for her activities and died in prison.

While on the train to freedom, Shula left her sleeping children with her husband and walked to the next car. Upon her return, she saw her husband frozen with fear and the conductor yelling, “These are forged passports!” The conductor had noticed that their daughter Esther’s hair was red, and on the passport she was listed as brunette. Approaching her sleeping daughter and wagging a finger at her, she said, “I told her not to play with dye! Now look what happened to her hair!” The conductor accepted the answer.

The family reached a refugee camp in Poking, Germany, where Zalman Kazen studied shechitah (kosher ritual slaughtering) on the advice of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Along with many other Chassidim, the Kazens settled into a chateau on the outskirts of Paris that had been converted into a communal residence. Every Shabbat, the women would sit in the yard while the girls sang and entertained them. There was a sickly woman with a few children who never joined them. Shula would talk to her, help her dress her children and walk her down the steps, telling her that the children needed fresh air.

Another woman gave birth to twins. Shula was told that the twin girls were lying naked on the floor because the family had no money to buy clothing. At that time Shula had five daughters and was quite weak herself. She dragged herself to a flea market, bought material, and sewed undershirts, sweaters and hats for the infants.

A New Life in Cleveland

In 1953, after seven years in Paris, with the assistance of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the family arrived in New York. HIAS had arranged housing for them in Cleveland, Ohio.

After years of travel and uncertainty, the couple wanted to settle in New York and raise their children near the Rebbe, but the Rebbe told them that they were needed in Cleveland, and they gladly prepared to move.

Before they left, the Rebbe asked Reb Zalman what he planned to do once he arrived in Cleveland. He responded that he planned to continue the watch business he had started, but the Rebbe suggested that he work as a shochet, a chazzan (cantor), or a congregational rabbi.

He would end up doing all three, and he and his wife would have a profound effect on the Jewish community there.

Soon after the move, the Rebbe instructed them to work with local Jewish families and strengthen their connection to Judaism. The Kazens knocked on doors and invited neighbors to join study groups on Shabbat.

Later Rabbi Kazen was appointed as the rabbi of the Tzemach Tzedek shul. The Kazen girls used to host Shabbat gatherings in their home. They would pick girls up, bring them to their home, serve refreshments and tell them inspiring Jewish stories.

Since her husband worked full-time as a shochet, Mrs. Kazen did most of the outreach work. She was appointed president of N’shei Chabad, which was mostly for older European-born women. At the Rebbe’s behest, she opened another organization for younger women.

With the Rebbe’s encouragement, the Kazens arranged that chalav Yisrael kosher milk become commercially available in Cleveland. At the time, they spent more than half of their meager income on the endeavor, but they were determined, and their efforts bore fruits. Following the Rebbe’s advice, they arranged that the day school, Hebrew Academy, serve chalav Yisrael, which inspired families to procure the milk for their homes as well.

Together with her daughters, Mrs. Kazen ran weekly Mesibos Shabbos gatherings for local girls—many of whom were inspired to transfer to Hebrew Academy and are now grandmothers of observant Jewish families.

The Kazens’ synagogue was the center of their activities, often full of clothing and foodstuffs Mrs. Kazen collected for needy families in Ohio as well as for her other “pet” causes in Israel. As guided by the Rebbe, after a terrorist killed five students in 1956 at the vocational school in Kfar Chabad, Israel, she collected funds, equipment and other supplies to furnish their new facility.

It didn’t matter that she was a mother of a large brood and that she had barely a penny of her own. There were people who needed help, and she would do what it took to help them.

“Together with her husband, Rebbetzin Kazen contributed to every facet of Jewish life in Cleveland,” said Rabbi Simcha Dessler, a Cleveland native who now serves as educational director of Hebrew Academy. “She had an intense love for Judaism, a love for Jewish people, and a sparkling personality. No one could say no to her.”

‘The Queen of Cleveland’

When Rabbi Kazen would pass by the Rebbe to receive a dollar and a blessing, the Rebbe would ask if his wife was waiting in line as well. If not, he would give him a dollar for her, too. On one occasion, the Rebbe referred to her as di malka fun Cleveland, “the queen of Cleveland.”

Indeed, Mrs. Kazen had a regal aura about her. However, unlike a queen, she was never afraid to get her hands dirty.

She would spend days and nights cooking meals for people in need and always kept a pot bubbling on the stove, ready to serve whomever might wander in.

When the Iron Curtain began to part, Russian immigrants started to stream to Cleveland. Mrs. Kazen would meet new arrivals at the airport, find them employment and lodging, and supply them with furniture and clothes. At times, she would take in families to stay in her own home—sometimes for weeks or months at a time—until they found a place of their own.

She would encourage the new immigrants to register their children in the Hebrew Academy. Week after week, she would come to the school with students, who spoke no English, had no prior Judaic education, and could offer nothing in the way of tuition.

According to Rabbi Dessler, the “scores of families” Mrs. Kazen brought to Hebrew Academy resulted in generations that have adopted an observant lifestyle and have been absorbed into the Cleveland Jewish community.

At a certain point, the demand became so great that the school opened a special New American Division, with an enrollment of 120.

She was also active in encouraging Russian men and boys to undergo brit milah (circumcision), the very mitzvah for which her father had given his life. All told, she arranged 500 circumcisions. In the days and weeks following the procedure, she would don a white nurse’s coat and change the bandages herself, caring for every “patient” as her own son.

In 1971, Mrs. Kazen was asked if Cleveland would host the Mid-Winter N’shei Chabad Convention. Knowing that the lion’s share of the burden would fall on her shoulders, Mrs. Kazen told the Rebbe that her plate was too full and she could not do it. The Rebbe encouraged her, saying that her children would help. She cooked and baked for days on end to prepare for the massive gathering, and the convention turned out to be a great success. At the Motzei Shabbat session, couples were invited.

The guest speaker was Dr. Velvl Greene, who also spoke for students at nearby Case Western University. The gathering gave birth to the first Chabad House in Cleveland, which was subsequently run by her daughter, Devorah, and her husband, Rabbi Leibel Alevsky.

Mrs. Kazen encouraged many young men and women to study at the Chabad yeshivahs on the East Coast.

At one point a young man told her that he was planning to drop out of yeshivah in Morristown, N.J. Immediately, she drove from Cleveland to Morristown, a distance of 450 miles. When she arrived, she found the student all packed and ready to leave. She convinced him to write to the Rebbe. The Rebbe told him to learn for a year and then ask again. Today he is the father of a large religious family.

On another occasion, she hosted a group of yeshivah students who had come from New York to attend the wedding of a friend. Upon seeing their stained and rumpled suits, she had them dress in her husband’s clothing while she washed and ironed their suits. Only then did she allow them to go to the wedding hall.

Mrs. Kazen’s wise and incisive advice helped smooth out many a tiff between spouses. One piece of advice, which a woman credited with saving her marriage: “When he talks nicely, he is talking to you. When he is yelling, he is yelling at the wall behind you.”

Continuing to Serve into Their 90s

Even as they aged, the Kazens continued to serve their community with the energy of a young couple.

Mussi Alpern, a great-granddaughter, recalls visiting the Kazens when the couple was already deep into their 80s.

“We arrived at 6 a.m. Friday morning and went straight to the shul. Outside we met Zaidy, then 88, shoveling snow around the shul, while Bubby was already in the kitchen cooking. After a few minutes, Zaidy was in the car, driving to pick up people who could not come by themselves to shul. This was a daily pickup. All Friday, they did not stop for a second until all the food was cooked, the table was set and the place was spotlessly clean.

“It was less than an hour to Shabbos and I thought we were finally done. Then Bubby said with all her energy, ‘We still have time to make banana cake!’ For the Friday night meal, there were ‘only’ 20 guests. (At the Shabbos day meal, there were 150 guests!) Sitting at the Shabbos table was a pleasure, between Zaidy’s singing and divrei Torah, and Bubby’s delicious food.

“When we finally went to sleep it was past 1 a.m. I couldn’t believe it when I saw Bubby and Zaidy lie down to sleep on the hard wooden benches in shul. They would sleep there every Shabbos, as it was too far for them to walk home.

“When we woke up in the morning Bubby and Zaidy were already up. We asked Bubby, ‘So when do you rest?’ She answered, ‘I was educated that we rest after 120.’ After davening, everybody sat down for a full Shabbos meal with Zaidy’s niggunim and divrei Torah.

“On Motzoei Shabbos they prepared a big melaveh malkah meal for the community, which ended after midnight. But they still were not ready to sleep. They had to prepare for Sunday. We went out to the bakery to pick up the leftover bread and cakes, and prepared boxes of food for over 100 needy families who would come to the shul each Sunday morning for their food packages. While we were preparing the boxes, a snowstorm started, so they spent another night on hard benches.

“In the morning when we woke up, Zaidy was again shoveling the sidewalks around the shul. Right after Shacharis, people started to come to pick up their packages. While Bubby spoke and sang with the ladies, Zaidy approached the men, with simplicity and love, to put on tefillin. By then it was time for us to leave to the airport.

This was their routine for decades, which the couple stuck to until Rabbi Kazen passed away in the summer of 2011 at the age of 92.

Mrs. Kazen was predeceased by her son, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Kazen, pioneer of Judaism on the internet and founder of Chabad.org, and daughter Esther Alpern, Chabad-Lubavitch emissary to Brazil.

She is survived by her children, Devorah Alevsky, Cleveland; Henya Laine, Brooklyn; Blumah Wineberg, Kansas City; Rivka Kotlarsky, Brooklyn; Rochel Goldman, Johannesburg, South Africa; and hundreds of grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren across the world.

She is survived by her sisters, Rosa Marosov and Rochel Levin, both of Brooklyn.

Donations can be made to the food bank the Kazens ran (kosherfb.org) or go towards the Torah being written in their memory (mail to: 4481 University Parkway, Cleveland, OH 44118). The family asks that memories be shared via email to: [email protected].

Join the Discussion