The 1870s were an era of rapid growth for Chicago. Following the Great Fire of 1871, the scrappy city—known for soaring buildings, sooty factories and stinking stockyards—was rebuilding at breakneck speed. The burgeoning Jewish community, based in the near west side, was attracting thousands of new immigrants from Eastern Europe every year. In 1875, a group of Chabad Chassidim banded together to found a congregation they called Anshei Lubavitch (“Men of Lubavitch”).

There, they hoped, they would study Torah as their ancestors did; worshipping in the Chassidic manner, contemplating Chassidic teachings and then praying at length; and inspire each other to remain steadfast in their devotion to Judaism. They and their successors have done just that for almost 150 years; Anshei Lubavitch exists to this day as the oldest Chabad congregation in Chicago.

Precious little is known about the early years of congregants and the synagogue structures in which they prayed. Synagogue stationery produced in 1963 notes that the congregation was then in its 88th year, putting its founding in 1875. However, the 50th anniversary was celebrated with great fanfare in the fall of 1942, putting the founding in 1892.

A turning point in the life of the congregation took place around the turn of the last century, when the rabbi who would lead it for almost 25 years, Rabbi Mordechai Zevin, then around 50 years of age, set foot in the Windy City from Russia.

An Esteemed Rabbi Arrives

Before leaving Russia, Zevin discussed his plans with Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, who would eventually become the sixth Rebbe of Lubavitch. At the time, Rabbi Sholom DovBer Schneersohn, the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, praised the departing rabbi to his son, referring to him as “an entirely Chassidic Jew ... with an old-fashioned delight in Chassidic teachings.”

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak reminded Zevin how G‑d is everywhere and how mere space cannot sever a person from G‑d, and how each person has a Divine mission to encourage others and increase in Torah observance. With the Rebbe’s words ringing in his ears, Zevin set to work recreating the spiritual world of Eastern Europe on the shores of Lake Michigan.

For the first two decades of the 20th century, Anshei Lubavitch and Jewish life in general thrived under Zevin’s leadership. An article in the May 30, 1916, Chicago Jewish Sentinel reported on the upcoming ninth graduation of the Deborah Sabbath School, whose classes were held at Anshei Lubavitch. An article from the previous year reports an enrollment of 250 girls. While the girl’s school appears to have met only on Shabbat and Sunday, a boy’s division had classes daily.

In a letter written in the winter of 1922, the sixth Rebbe told Zevin that he had only recently received his address and was, therefore, taking the opportunity to write him. He went on to recall the subject of their conversation twenty years earlier. Apparently, there was an exchange of letters, because in a letter dated 10 Elul (late summer) 1923, the Rebbe wrote to someone else, expressing his joy at the good tidings that 300 young men were studying Talmud there in a manner reminiscent of the study schedule established in the town of Lubavitch.

The children at these schools were taught more than just Hebrew reading and rudimentary Judaism; Ahavat Yisrael, a love and care for others, was part and parcel of their Chassidic education. A notice in the Sentinel from March 17, 1916, reports that at a Purim celebration held in conjunction with students from several other congregations, the children “will exchange Purim gifts with one another and spare part of their money to send to the suffering children of the European war.”

A towering figure in the congregation’s religious school, as well as a major force behind the development of Jewish education in Chicago, was Naftali Hertz (Nathan) Bolotin. A successful merchant, Bolotin took a leading role in founding and leading the Hebrew Theological College, which provided the Midwest with a steady stream of Orthodox rabbis for most of the 20th century.

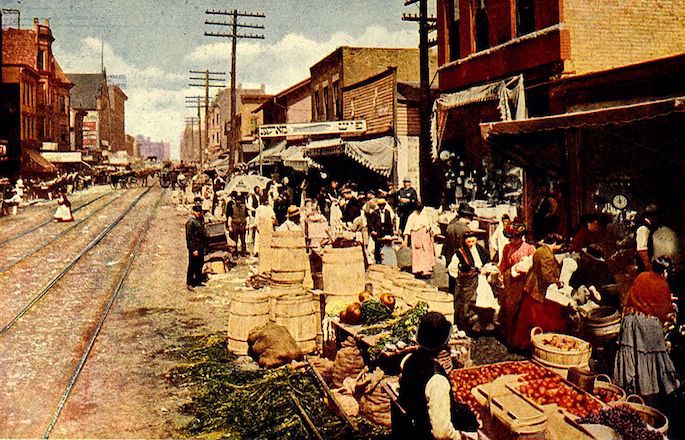

News reports from those years list the congregation’s location as the W. Maxwell Street and S. Newberry Ave., the heart of the Jewish community at that time. An open-air market served and patronized primarily by Jews, Maxwell Street was a bustling and dizzying center of Jewish life.

Made up of mostly older wooden buildings that had survived the fire, the neighborhood was the first point of entry for Jewish immigrants arriving in Chicago by rail or boat. As the community became more established, people moved mostly westward to the up-and-coming Lawndale district.

Led by Zevin, the congregation built a tan brick edifice in the new neighborhood, located at 1500 S. Drake Ave. (then called Clifton Park), just a block away from the stately Douglass Boulevard. Even after the founding of the Lawndale location, contemporary news reports indicate that Anshei Lubavitch continued to operate at Peoria Avenue (two blocks from Maxwell Street) into the 1920s.

The synagogue inauguration was widely reported in the press. According to the Daily Jewish Courier (Sept. 4, 1922), “The ceremony began with a big parade from the congregation’s temporary home at Albany Avenue and Roosevelt Road. The members of the synagogue, carrying the sacred articles, marched to the new synagogue preceded by a band from the Marks Nathan Orphan Home. Rabbi Judah Leb Gordon marched side by side with the rabbi of the congregation, Rabbi Mordecai Zevin. Many pedestrians joined the march and many people rode in autos ... ”

During the course of the celebration, an impressive $5,000 was raised.

“The building was not tall but it was impressive, and it had a men’s mikvah in the basement,” recalls 89-year-old Ephraim Moscowitz, who grew up attending the Lawndale location. “It was a thriving center of Chassidic life in Chicago, along with Bnei Ruven, which was a mile away, Tzemach Tzedek in Wicker Park, Nusach Ari in Albany Park, and later, Agudas Chabad in Uptown.”

Correspondence With Europe

Just a year later, on Friday, July 27, 1923, Zevin passed away suddenly at the age of 75. According to a report published in the Sentinel and other outlets, more than 10,000 Jews attended his funeral, which wended its way from one synagogue to the next, as the collective Chicago Jewish community mourned the loss of a great teacher of Torah.

The news took several months to reach Russia, where the Sixth Rebbe was then actively fighting for the survival of Judaism. In a letter dated 19 Cheshvan (Oct. 29) the Rebbe wrote to “our dear friends the Chassidic community in Chicago,” comforting them for the “great loss of tremendous magnitude” and exhorting them to continue in the ways of their rabbi, to strengthen Judaism and promote Torah study.

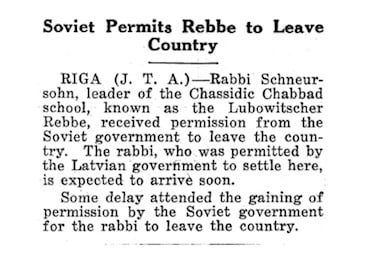

The lively correspondence between the Chicago community and the Rebbe continued, especially after the Rebbe escaped from behind the Iron Curtain and made his way to Riga, Latvia.

In honor of the wedding of the Rebbe’s daughter, Chaya Mushka, to his eventual successor, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Rebbe replied to no less than three congratulatory letters: one from the presidents, Bolotin and Shimon Aronin; one from the congregation as a whole; and another from Mendel Sevin (son of Rabbi Mordechai Zevin, who changed the spelling of his name to Sevin), who had sent his congratulations by way of Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu Elkin, who was then leading the congregation.

It was reported that when Elkin would speak on Shabbat, as many as 700 people would crowd into the sanctuary, which had seating for 450.

Thousands Throng to Greet the Sixth Rebbe

In early 1930, as part of a trip to Israel and then the United States, the Rebbe visited Chicago. The Chassidim, who had longed to lay eyes on the Rebbe, as well as thousands of other Jews who wished to meet the famous defender of Jewish life, thronged to greet him.

On Monday, Feb. 10, 1930, The Chicago Tribune reported that the Rebbe’s arrival “caused great excitement in the LaSalle Street station yesterday as several thousand orthodox Jews fought to get a glimpse of their leader.

“When Rabbi Schnayerson [sic], whose followers in Russia and Poland number more than 3,000,000, appeared on the platform of the train, there was a rush forward. Several persons were trampled upon before policemen arrived to restore order.”

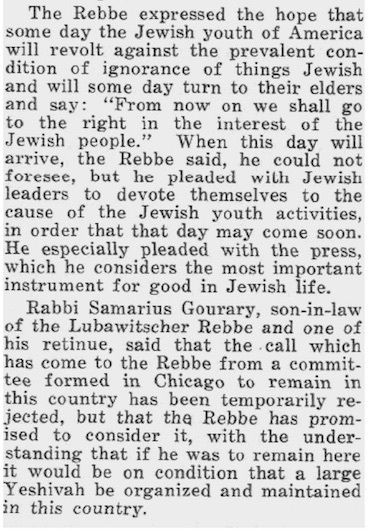

The Rebbe’s entourage was paraded to Douglas Boulevard, where a stage had been set up on the street, from which the Rebbe addressed the crowd, which filled the boulevard.

This visit bolstered the Rebbe’s involvement with the Chicago community, whose leaders had invited him to settle in Chicago. According to a report by the J.T.A., the Rebbe declined the invitation, but “promised to consider it, with the understanding that if he was to remain here it would be on condition that a large Yeshivah be organized and maintained in this country.”

Throughout the coming decade, the congregation continued to function and maintained its afternoon school, known as a Talmud Torah, in an adjacent flat. A notice in the Sentinel from June of 1939 announced that noted Cantor Pierre Pinchik would lead Shabbat services at the congregation and then hold a concert on Sunday “to benefit the free daily Hebrew school conducted by the congregation for two hundred children.”

When the Rebbe returned to the United States after being spirited out of Nazi-occupied Poland, the Chicago Chassidim longed to have the Rebbe visit their city once again.

On Sukkot of 1941, a delegation of Chicago dignitaries spent the holiday in the Rebbe’s newly transplanted court in New York with the purpose of extending an invitation to him. The Rebbe agreed, and on Sunday, Jan. 25, 1942, the Rebbe arrived by rail to Chicago for a second visit.

Among a whirlwind of meetings with community leaders, rabbis, activists and journalists, the Rebbe made sure to meet with the Talmud Torah students, including those at Anshei Lubavitch.

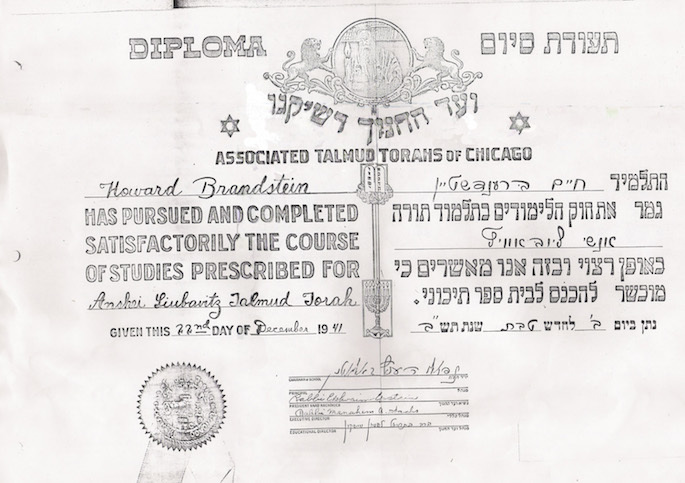

“My father remembered that meeting very fondly,” says Matt (Moshe) Brandstein, regarding his father Howard (Chaim) Brandstein, who passed away three years ago. “With reverence, he would talk about it as one of the holiest moments of his life. He described the Rebbe as a short man with a white beard, and the impression was something that stayed with him for the rest of his life. Everyone was excited and everyone was talking about the great honor they had to host the Rebbe. He was given a seat at the eastern wall of the shul, and it was the happiest time.”

Howard Brandstein grew up attending the congregation, and his maternal grandparents, Mendel and Ida Richman, who had come to Chicago from Postov, Russia, were among its earliest members.

The Rebbe also met with a delegation of the Talmud Torah’s staff, led by Bolotin. The Rebbe shared his concern regarding the fact that they were using textbooks that excerpted just portions of the Chumash, and they promised to remedy the situation as soon as possible.

Just one week into the visit, the Rebbe received the heartbreaking news of the passing of his mother, Rebbetzin Shterna Sarah Schneersohn, in New York. Forced to cut his visit short, he delivered his parting address with tears in his eyes from the bimah of Anshei Lubavitch.

The brief visit left a lasting impression that is still remembered today.

A Search for New Leadership

But not all was rosy. More than half-a-century after Jews had arrived en masse to Chicago, the children and grandchildren of the original immigrants had drifted away from the Jewish ideals they had been raised with.

Along with many of Chicago’s synagogues, Anshei Lubavitch needed new leadership—a rabbi who could remain faithful to its Chassidic underpinnings and reach out to a generation of American Jews with warmth.

And of course, just as important, if not more important was that the rabbi come with a talented and motivated wife, a rebbitzen who would be able to reach out to women and guide them.

In a flurry of letters and personal meetings between the Rebbe and the synagogue congregation, it was decided that the Rebbe himself would choose their spiritual leader. But finding such a leader proved to be difficult. “The Lubavitch congregation needs a rabbi who is G‑d fearing, who speaks English and Yiddish, a communal activist, an energetic worker, who will care for every aspect of the congregation and the Talmud Torah,” the Rebbe wrote to Bolotin in the summer of 1942. “Such a person you need, and such a person is not so easy to come by. I have such an individual, and thank G‑d he already has a position.”

The candidate the Rebbe had in mind was none other than Rabbi Shlomo Zalman (Solomon S.) Hecht, who had studied in Israel and in the Rebbe’s yeshivah in Otwock, Poland. His wife, Chaya Sora, was the daughter of the noted Chassidic activist, Rabbi Yisroel Jacobson, who had in many ways laid the groundwork for the Chassidic renaissance in the United States.

The young rabbi was American-born and his wife was born in the Chassidic city of Homel (Gomel) and raised in America.

The Hechts were among a handful of young couples of their generation to adhere fully to a Chassidic lifestyle. He sported an untrimmed beard, and when she went to be fitted for a wig before her wedding, the wigmaker burst into tears, not believing that a young American woman was willing to devote herself to the mitzvah of covering her hair.

Indeed while the young couple were living in Poland, the Rebbe had told her the words that he would repeat again upon coming to American shores several years later: Amerika iz nisht andersh, “America is no different” and there is no reason not to live in accordance with time-honored Chassidic ideals.

Although the rabbi was then serving in the Winthrop Avenue Synagogue in Brooklyn, N.Y., and it would be a challenge for them to move away from their parents, the Rebbe was confident that the devoted couple would gladly move to Chicago if he suggested it.

In order to ease the transition, it was decided that he first visit as the guest of honor for the congregation’s 50th-anniversary celebration, so that he and the congregation would become better acquainted.

Finally, as 1942 came to a close, the Hechts relocated to Chicago.

Before they departed, the Rebbe gave Chaya Sora Hecht three pieces of advice: to get household help, to teach, and to involve herself in communal endeavors.

Almost immediately, the young rabbi began making changes, both within the congregation and the city. He instituted an advanced class in the Talmud Torah, encouraged Torah study throughout the area and upgraded the city’s kosher supervision.

“Rabbi Hecht was extremely striking,” recalls Moscowitz. “He had a full beard—something we only saw on elderly visiting rabbis from Europe—wore a long frock and exuded a feeling of authority.”

He rolled up his sleeves and got to work. In the basement of the synagogue, he would boil up vats of hot water before Passover and assist people in koshering their cutlery and dishes for the spring holiday.

Under his supervision, the congregation expanded its humanitarian efforts. He solicited and oversaw the delivering of wooden crates of food for the needy before Jewish holidays and spearheaded a citywide effort to bring kosher food to Jewish men serving in the U.S. armed forces.

As per the Rebbe’s instruction, the congregation was to invite the other Chabad congregations—and then all other synagogues in the city—to join them in the effort, and the kosher standard was to be scrupulously upheld.

Despite the many vital services he provided, the rabbi was particular never to charge for his work. He and his wife preferred to live simply on the modest salary that they were provided.

Rebbetzin Hecht began making inroads as well. One Purim, the rabbi traveled to New York to be near the rebbe. His wife decided to host a large celebration at home. This became an annual tradition that would continue for decades. The rabbi would speak, and crowds of people would come in to snack, say l’chaim and bask in the chassidic atmosphere.

“Rebbetzin Hecht would prepare for the open-house months in advance,” recalled Mrs. Harriet Turner in a tribute released by the seniors of Lubavitch Girls High School in 1994. “Everyone was welcome and I even remember her moving out the furniture to the backyard to make room.”

Regarding those years in Lawndale, Moscowitz fondly remembers the bustle of Chassidic life that went on, recalling the Levitansky brothers who would form a choir to accompany the High Holiday prayers and others.

But the postwar boom saw a drastic shift in demographics, and the Jews moved further away from the city center, this time setting their sights northward.

Recognizing the need to move once again, Anshei Lubavitch purchased a property on the far northeastern corner of the city, just blocks away from Lake Michigan. The neighborhood of their choice, Rogers Park, was made up of stately large homes and solid brick apartment buildings.

The congregation’s new home at 7424 N. Paulina St. was a two-story brick home with an empty lot next door, where they hoped to one day construct a Talmud Torah.

Alas, the growth they had hoped for didn’t come, and the Talmud Torah was never built. Although the neighborhood was safe in those years, the major Jewish settlement was in West Rogers Park, around three miles to the west.

Nevertheless, the Hechts’ inspiration and magnetic personality did attract a group of devoted students and admirers.

“We chose to live in Rogers Park specifically because we wanted to be close to Rabbi and Rebbetzin Hecht,” says Moscowitz, now the patriarch of a large Chabad family. “Through them, people developed a connection with the Rebbe and Chabad.”

“Mrs. Hecht was quite the leader,” adds his wife, Cynthia (Tzivia) Moscowitz, who was introduced to the Hechts by her husband around the time of their marriage. “She taught, organized, mentored and was a confidant to many.”

She was the acknowledged head of Neshei Chabad, the Chabad-Lubavitch women’s organization, whose events were attended by women from across the community. She was also instrumental in founding Daughters of Israel, which promotes and facilitates mikvah use in the city. She gave many classes to women and taught in an afterschool Talmud Torah for decades.

The atmosphere in the synagogue in those years was homey and welcoming.

Having not been raised in an Orthodox setting, Moscowitz recalls being inspired by the European-born ladies she met in the synagogue. “On Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, they would cry during davening. It was very special and very beautiful.”

At sisterhood gatherings, the women would often come up with reasons for which they could contribute donations of $2 or $3. Weddings, anniversaries, yahrzeits, or other milestones were all good “excuses” to raise some funds for their beloved congregation.

“These were not rich people,” recalls Joseph Hecht, regarding his parents’ congregation. “They were kind, sincere and warm Jews, a very special group.”

Among the notable members of the group were Izzy Nathan, who spearheaded the city’s mezuzah campaign; Wolf Schiffman, a carpenter who built some of the synagogue’s furniture; and Reuven Stoller, who took care of laying out the spread for the Kiddush and caring for the synagogue’s other needs. Other families associated with the congregation in those years included the Weinschneiders, the Osinas and the Danzingers, among others.

Of special note was Jacob (Yankel) Katz, listed as the congregation’s president on its stationary. The son of a Chabad Chassid with a long beard, Katz was deeply connected to the seventh Rebbe, who had formally assumed leadership in 1951.

Even though Katz lived in a different neighborhood (Albany Park), he would stay in a low-class boarding house with his wife for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur to lead the congregation in prayer. As a Kohen, he took the dual duty of leading the congregation and conferring Birkat Kohanim, the priestly blessing.

It was an inconvenience, but the Rebbe insisted that Katz do it until his failing eyesight prevented him from continuing after the High Holidays of 1974.

By that time, the neighborhood had long since lost most of the small Jewish presence it had garnered.

Keeping a Declining Congregation Alive

In the mid-1960s, Rabbi Hecht accepted a rabbinic position at the large and well-established Warsaw Bickur Cholim Congregation in Peterson Park.

In a private audience with the Rebbe, he shared his plans to close down the old congregation, explaining that “there is nobody there anymore.”

“But the Aibershter [G‑d] is still there,” replied the Rebbe.

Noting that the congregation was especially dear to his father-in-law, the Rebbe advised that as long as there was a minyan attending, the shul should remain open.

To facilitate this, Hecht enlisted the help of local Rabbi Dov Warshavsky, an accomplished scholar who had studied in Grodno under Rabbi Shimon Shkop, and the synagogue stayed alive with a small but dedicated group of elderly members.

In the mid-1970s, the Rebbe once asked Hecht how things were going at Anshei Lubavitch, and the rabbi was forced to admit that he did not know. The Rebbe instructed him to stay in touch with the old shul, and from then on, every few weeks Hecht would ask Dr. Arthur Lubin, a young mathematician who attended his Wednesday night Ohr Hachaim class, to report on any new developments.

The Rebbe’s request also led to a special reunion Shabbat in the summer of 1975, when Hecht and some of the old members of the congregation, including Nathan and Victor Katz, walked four miles for an inspirational gathering at the shul.

In 1977, Lubin, who had since married and started a family, moved to West Rogers Park, yet he continued to walk every Shabbat to the little synagogue.

By 1985, the synagogue was no longer able to function. Rabbi Hecht had passed away in 1979, Rabbi Warshavsky passed away in 1984, and almost all of the members were gone.

Nathan, Lubin and Moscowitz continued to care for the congregation’s legal standing and recordkeeping (including maintaining the cemetery plots), but who would pray there?

Their salvation came from within. Among those who had prayed regularly at the congregation in the decades past was a certain young boy named Arthur Kohn.

Now an optometrist with a practice of his own, his wife, Charlotte, had been appointed as the executive director of a nearby nursing home, Birchwood Plaza. Charlotte Kohn’s parents were the longtime proprietors of a kosher nursing home that housed a synagogue, and she wished to have the same amenity in the nursing home she was now directing.

Aware of the plight of the synagogue struggling to remain alive just a few blocks away, she invited Anshei Lubavitch to move into Birchwood. She requested that it take the additional name of Bnai Moshe, in memory of her father.

Knowing that the Rebbe himself had insisted that the congregation remain open, Lubin and Nathan turned to Rebbetzin Chaya Sora Hecht for her advice. She directed them to consult the Rebbe directly.

Lubin wrote up the situation and gave it to Hecht, who sealed it in her personal stationery envelope, which she addressed to the Rebbe. She then took that envelope and put it in a second, personal envelope, which she addressed to Rabbi Chaim Mordechai Aizik Hodakov, the Rebbe’s chief of staff and personal secretary.

The Rebbe responded to the letter by saying that they should ask this question to a rav, a recognized Jewish legal scholar. Hecht then asked her brother-in-law, Rabbi Mordechai Altein of the Bronx, N.Y., to bring the question to Rabbi Zalman Shimon Dworkin, rav of Lubavitch.

Dworkin was very ill at the time (he passed away in 1985, a short time after this incident), and when he heard that they were considering closing the synagogue, he began sobbing. Through tears, he shared that he remembered this shul’s glory days and lamented that so many venerable synagogues were closing down. He then ruled that if moving would allow the shul to remain open, that was how they should proceed.

Kohn and her staff welcomed the congregation with open arms, renovating a room in the facility’s lower level and decorating it appropriately. She was joined by administrator Abraham Schiffman, whose father, Wolf Schiffman, had been a close member of Hecht’s circle.

Lubin then volunteered to walk the three miles each way from his home each week to lead the full services, including the reading of the Torah. In the freezing Chicago winters, and the hottest of summer days, he has continued his walk each week, ensuring that the minyan would continue.

Much of the burden was carried by his late wife, Leba Chana (Eloise) Lubin, who passed away on Oct. 30, 2018. An interior designer by trade, she was a natural nurturer and a sensitive friend to many. Despite the ups and downs of the neighborhood, the freezing weather and the loneliness she endured on Shabbat mornings, she encouraged her husband’s weekly visit, knowing that he was needed at Birchwood. On weeks that he cannot make it, Birchwood Plaza's devoted activity director, Jacob Moraine, fills in for him.

For the Kohns, caring for the congregation has been something of a family affair. Every year on Sukkot, the Kohn boys would attend services there and host the residents for a lavish meal in the sukkah.

The synagogue’s presence in the nursing home has afforded countless residents the opportunity to pray with a minyan on Shabbat and holidays. Rabbi Yehuda Goldman, the senior Orthodox rabbi in Chicago, who passed away in 1993 at age 103, lived his final years in Birchwood and attended every Shabbat.

Lubin admiringly tells of the elderly Jews who use their last strength to make it downstairs to services, including amputees, stroke victims and others with very limited mobility.

In recent years, the nursing home has become less Jewish, and it has become harder to garner a minyan on a weekly basis. For the past several months, Lubin has been accompanied on his walk with rabbinical students.

One neighborhood resident who has recently become a regular attendee is Matt Brandstein, who was encouraged to attend the services by Rabbi Yoel Wolf, who directs the closest Chabad center, Chabad of East Rogers Park. He was delighted to discover that the small synagogue (which currently has no sign) is the legendary Anshei Lubavitch his ancestors had attended more than a century ago.

When asked about the synagogue’s prospects, Kohn hopes to attract more Jewish people to the nursing home, a place where they can keep kosher and attend synagogue regularly.

And if history is any indicator, chances are the synagogue will find a way to exist. It always has.

Join the Discussion