For four days this week, some 500 Chabad-Lubavitch rabbis from across Europe are gathering in Moscow, Russia, for the largest rabbinical summit in recent European history. The historic meeting, which underscores the unprecedented growth of Jewish life and infrastructure in Russia during the last quarter-century, is not taking place in Moscow alone, however. On Sunday evening, fleets of buses departed the Russian capital, ferrying the rabbis—who hail from nearly every European capital and country—to the tiny villages where the movement was born nearly 250 years ago: Lubavitch (Lyubavichi), Russia; Liozna, Belarus; and Liadi (Lyady), Belarus.

On Tuesday, the group boarded flights to Almaty, Kazakhstan, where they will mark the 72nd anniversary of the passing of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, the father of the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—who is buried in the central Asian city where he died in Soviet-imposed exile in 1944.

While certainly momentous, it’s not the first time that Chabad has chosen Russia to host its annual European gathering. Back in the summer of 1991, 170 Chabad rabbis arrived in the terminally ill Soviet Union for the first time to inspire a land that had been sealed off for generations and to witness the beginnings of what has since become the greatest renaissance in Jewish history.

“It took place in [Soviet leader Mikhail] Gorbachev’s final months in power,” remembers Rabbi Moshe Kotlarsky, vice chairman of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch—the educational arm of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement—who flew from New York at the time to run the gathering. “It was very emotional for all of us. We landed in Moscow’s airport, and there was an announcement in Russian, English and Hebrew welcoming the emissaries of the Lubavitcher Rebbe to the Soviet Union. At the time, who could have imagined such a thing?”

Among that first group were a number of Russian-born emissaries who had fled the Soviet Union years earlier, such as Rabbi Issocher Dov Gurevitch, the longtime director of the Beth Rivkah Lubavitch girls’ school in Yerres, France, who passed away in 2008 at the age of 93. Gurevitch had been imprisoned twice by Soviet secret police and illegally escaped in the late 1940s. The rabbi was terrified to return to the country of his birth.

“He was extremely scared when he gave his passport to the Soviet customs agent,” says his grandson, Rabbi Mendel Gurevitch, who is attending the current gathering as a rabbi from Germany. “When he saw what was going on with Judaism in the USSR, he was amazed. He talked about it for years later.”

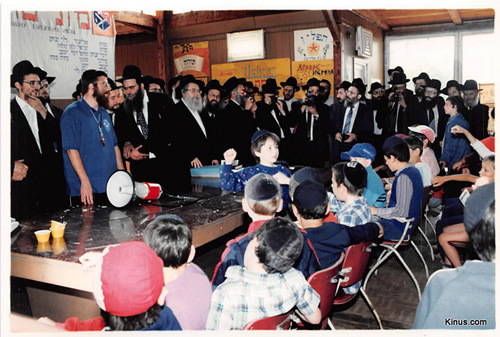

The elder Gurevitch was 23 when he and another Chassid were arrested after being caught teaching a group of children Torah in an empty synagogue in Berdichev, Ukraine. The children were sent to Soviet orphanages, and the two rabbis sentenced to a year of prison. Arriving back in Moscow in 1991, Gurevitch and his colleagues traveled to Chabad’s Camp Gan Israel—then in just its second summer—where he emotionally retold the story, asking the Russian Jewish children to “take full advantage of the new opportunities available.”

Twenty-five years later, his grandson, co-director of Chabad of Offenbach am Main near Frankfurt, is being amazed once again. In 1991, there were just three permanent Chabad rabbis in the USSR: Rabbi Berel Lazar in Moscow, Rabbi Shmuel Kaminezki in Dnepropetrovsk and Rabbi Moshe Moskovitz in Kharkov. Today, the Federation of Jewish Communities of the CIS (FJC) boasts a presence in more than 250 cities throughout the former Soviet Union, nearly 100 of them with permanent rabbis.

Walking through Moscow’s seven-story Marina Roscha Jewish Community Center, Gurevitch recalls a story his grandfather used to tell him about the old days, when Marina Roscha’s synagogue was little more than a wooden hut and attending it came at a heavy price.

“The police grabbed him, and told him they’d let him go if he agreed to report to their office once a week and report on all the activities in Marina Roscha synagogue,” recounts Gurevitch. “He went straight back to the synagogue and told everyone exactly what happened to him. Rather than inform, he ran away to Tashkent [Soviet Uzbekistan].”

These days, Tashkent has a Chabad presence as well. Would Gurevitch have been able to visit now, he would be greeted by rabbis and a chorus of children at the Ohr Avner Jewish Day School.

‘Like It Came Back to Life’

“Every town and townlet has its own chapter in Jewish history,” wrote Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, the Sixth Chabad Rebbe (1880-1950). “There are towns and townlets that represent in themselves complete movements and complete periods in Jewish life. Such a town, or rather townlet, was Lubavitch in Russia. During 102 years and 2 months, Lubavitch was the seat of four generations of Chabad Rebbes, and the center of Chabad Chasidism with hundreds of thousands of followers all over Russia as well as in other countries.”

In the fall of 1915, as World War I engulfed Europe, that period came to an end. The Fifth Rebbe, Rabbi Shalom Dov Ber, evacuated his Chassidic court from the village where his father and grandfather—leaders of Lubavitch—were buried and headed east to Rostov, Russia.

At that time, “Lubavitch ceased to be the seat of the Lubavitch Rebbes and the center of Chabad,” wrote Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak. “But the name ‘Lubavitch’ will always be bound up with Chabad Chasidism and will ever awaken sweet memories, and portray a wonderful chapter in Jewish history.”

In 1991, it took the rabbis 14 hours to reach the muddy village; nowadays, with newer roads and better buses, it takes seven. But the feeling, say participants, remains much the same.

“It was really unbelievable,” says Gurevitch by phone from a bus in Belarus. “All of these Chassidim walking along the streets of Lubavitch. For a few hours, if you looked around, it was like Lubavitch of old. It’s like it came back to life.”

On Monday in Lubavitch, the emissaries sang and prayed, gathering in a large white tent built for the occasion on the exact location of the historic court of the Lubavitcher Rebbes. Trudging along the perpetually muddy dirt roads, they made their way out to the long-silent Jewish cemetery, where an Ohel covers the resting place of the Tzemach Tzedek, Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch (1789-1866); and his youngest son and successor Rabbi Shmuel (1834-1883).

Each year in November, emissaries from around the globe gather in New York for the annual International Conference of Chabad-Lubavitch Emissaries (Kinus Hashluchim). It’s a time to meet old friends, to study and learn, and, as so many of them say, “recharge their batteries.” Regional gatherings take place as well, allowing rabbis in local areas to learn and share with one another. With Europe facing an alarming rise in anti-Semitism and a relatively recent onslaught of terrorism, Chabad rabbis—who serve from a majority of the continent’s pulpits, including in isolated places such as Malmo, Sweden, or Athens, Greece—see the coming together in Russia occurring at a particularly important time.

“Every kinus is important, and the shluchim come away invigorated,” says Kotlarsky, who was instrumental in arranging the current gathering. “But for Lubavitch—having grown to such a large extent in Russia, in Europe and around the world—to come back to Lubavitch, it’s really special.”

A Century of Growth

Back in 1991, the Rebbe gave his blessings for the gathering, During the weeks that followed, he referred to it as “wondrous recent event,” drawing attention to the fact that rabbis from across Europe had been able to gather in the village of Lubavitch and in the capital of the Soviet Union to “seek advice and discuss matters with each other ... and make positive resolutions to add to their work in the spreading of Torah and Judaism and spreading the wellsprings out into the entire country and the whole world.”

The Rebbe stressed the meeting’s uniqueness, and in a note to one of his secretaries said that it would be worthwhile for the group to visit the movement’s birthplaces of Liozna and Liadi, both of which are today in Belarus. The note reached the rabbis in Moscow late, and although they had made the trek to Lubavitch and the flight to the resting place of the Rebbe’s father in Almaty, they never did make it to the two Belarussian villages.

It was in Liozna that Chabad was first founded in the late 1700s by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, known as the Alter Rebbe, and it was there that his daughter Devorah Leah tragically passed away and was buried in 1792. After his second arrest by Czarist officials in 1801, Rabbi Schneur Zalman settled in Liadi, with which his name has been synonymous ever since. It was to Liadi that Napoleon Bonaparte famously came in search of the holy rabbi who stood in opposition to the French emperor’s conquest of Europe. These villages have been mostly empty of Jews since World War II, when the local populations were killed by the advancing Nazis.

On Monday evening, the emissaries’ buses crossed into Belarus, where they were greeted in each village by delegations of regional and local governments, as well as residents. “Every window was open; the people couldn’t believe their eyes,” says Gurevitch. “We had never seen these places, but they had never seen anything close to 500 rabbis.”

The group will fly from Moscow to Almaty, Kazakhstan, where they will pray at the gravesite of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson on his yahrtzeit, the 20th day of the Hebrew month of Av (starting on the evening of Aug. 23 and lasting through the evening of Aug. 24).

“This has been a momentous century and a century of change,” says Lazar, the chief rabbi of Russia. “One hundred years ago, Lubavitch left the village of Lubavitch. Seventy-five years ago, the Rebbe left Europe and arrived in America, which began a new phase in the work of Chabad. Fifty years ago, the Rebbe began speaking about ‘Uforatzta’—spreading out, creating the network that you see today. And 25 years ago, Communism fell and the Soviet Union crumbled, which was the beginning of the revival of Russian Jewry.

“It is important to mark milestones, which is what we are doing. But it also means that the work is not complete; the next step is just beginning.”

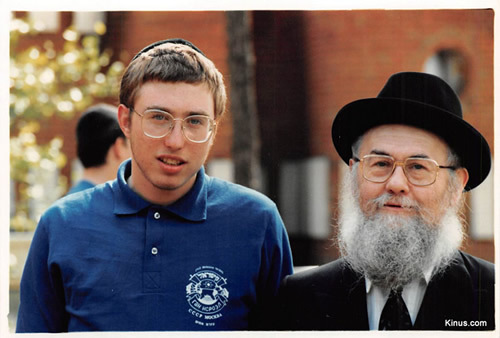

Photos From the 1991 Kinus in Moscow

Join the Discussion