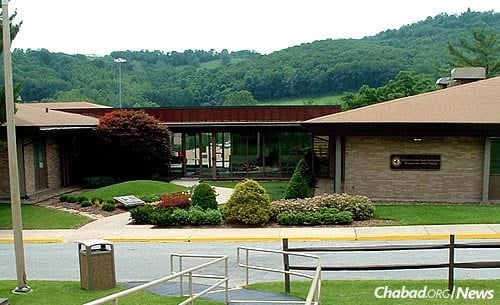

Most rabbis don’t consider close proximity to a prison a selling point when purchasing a home. But after living in Morgantown, W.V., for a few years, Rabbi Zalman Gurevitz wanted to move closer to both the University of West Virginia campus—and to the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI Morgantown) there.

Gurevitz and his wife, Hindy, have served the student body at the Rohr Chabad Jewish Student Center at West Virginia University since 2007. But he has another congregation of sorts: He visits a group of inmates at the minimum-security prison every Shabbat.

He is inspired by the concern for Jewish inmates expressed by the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. In the early 1980s, when incarceration rates in the United States started increasing dramatically, the Rebbe began talking more about the importance of spending time with and positively influencing people in confined environments.

“As a follower of the Rebbe and a student of the Rebbe, I knew how important it was to him,” said Gurevitz, who took over the duty started by a rabbi affiliated with the Pittsburgh-based organization Aleph Northeast. When Gurevitz moved to Morgantown, he was asked to take over the visits.

The Aleph Institute—a Florida-based organization founded under the direction of the Rebbe—is dedicated to assisting incarcerated Jews and their families, estimating that more than 5,000 Jews are currently in prisons across the United States. The organization also provides services and support to Jewish men and women serving in the U.S. military.

The Spiritual and the Physical

When it was first suggested that Gurevitz move to West Virginia, he was a bit uncertain. However, once he and his wife arrived with two children at the time—they now have three more—“we realized how important it is to be here because if we weren’t, the needs of many Jewish students would have never been met.”

Gurevitz primarily focuses on the university students. But a few months after he arrived in town, he got clearance to enter the prison.

On his first visit, recalled Gurevitz, one of the inmates said, “So rabbi, you’ll be back next week the same time?”

“I couldn’t say ‘no.’ So I said ‘yes,’ and I worked it out with the chaplain so we could come every week.”

The group had enough people to form a minyan (a quorum of 10 Jewish men necessary for public prayer) for the first time in 2010 and received a Torah that same year. In 2011, the rabbi started walking more than two miles each way to the prison every Shabbat. (Before he moved, it had been five miles each way; he went every other Shabbat.) He notes that he is motivated in part by the Rebbe’s classic work, Hayom Yom.

“When it comes to spiritual matters, you have to compare yourself to someone who is doing better than you,” he says. “When it comes to physical matters, you have to look at someone who is in a worse situation.”

‘A Jew Is a Jew’

Steven Kern used to travel around Asia as part of a group of volunteer chiropractors, and says he would study the dominant religion within whatever country he was visiting. In 2013, after being convicted of the willful non-filing of his income-tax return, Kern was sentenced to one year in prison.

There, he met some of the other Jewish inmates and started participating in services. Kern’s mother was Jewish, and he says he had read the Torah many times as part of his interest in religions, but didn’t know much about Jewish culture or prayers.

Gurevitz gave him a book to help him learn Hebrew, which he did while working in the prison laundry room. Eventually, Kern, in his 40s, had his bar mitzvah ceremony with the support of the rabbi. For Kern, the time in prison was transformative.

“I can say it was a wonderful experience in part because” I found my “Jewish heritage,” acknowledges Kern, who now lives in Michigan and observes Shabbat.

The Morgantown facility largely houses people convicted of white-collar crime, though Gurevitz makes it a point to say that he does not ask inmates about their convictions. Nevertheless, the rabbi still brings some muscle with him to help get the 10 people necessary for a minyan.

Jan Ditzian, 72, is a competitive powerlifter in the 132-pound weight class and lives just over the border in Pennsylvania. He comes each week for Shabbat and also tutors inmates in Hebrew during the week. Describing the prison as “extremely safe,” he says that most of its Jewish population, which includes lawyers, accountants and doctors, is “very intelligent.”

“They are good people to talk to,” says Ditzian, whose background is in industrial psychology. He had also been principal of a Jewish Sunday school in Morgantown and had previously connected with Chabad leaders in Pittsburgh. After Gurevitz moved to West Virginia, he reached out to Ditzian; eventually, the two started going to prison together.

While Ditzian belongs to a local synagogue, he considers the prison “my congregation.”

“They seem to be extremely appreciative, and that’s what I find rewarding about it,” he says. “They seem to like my coming.”

Aside from people like Ditzian, “the general Jewish community is not ready to accept felons,” states Gurevitz. As an example, the rabbi says he once had a scheduling conflict with someone on the outside and explained that he couldn’t change his schedule because of the strict rules at the prison. The person told him, “You better teach them to be good people.”

Yet the rabbi feels that “as a Chabad emissary, to me a Jew is a Jew, no matter what they did.”

After all this time working in the field, the rabbi says the subject of criminal justice has become somewhat personal. In fact, with recent talk of prison reform at the national level aiming to lower the incarceration rate, Gurevitz quips: “I’m the only rabbi who will be happy when I lose my minyan.”

Join the Discussion