The third in a series of articles on Chabad-Lubavitch summer camps.

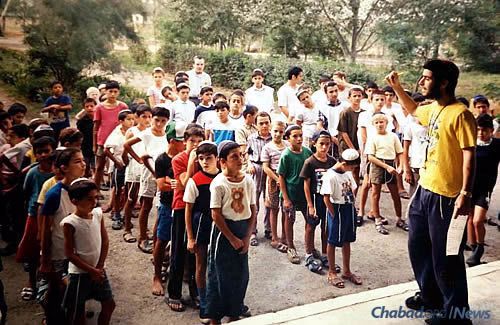

High on a flagpole some 70 kilometers west of Moscow, the green-and-white banner of Camp Gan Israel flutters in the breeze. Now in the midst of its 25th year, Gan Israel Moscow—a part of the Chabad-Lubavitch worldwide network of Jewish summer camps—draws more than 300 children for separate boys’ and girls’ sessions of overnight camp.

On the formerly well-ordered grounds of a Soviet Young Pioneer Organization’s camp—or pianerskee lager—kipah-clad boys and girls in skirts can now be seen playing sports, swimming or learning about their heritage throughout the sprawling campsite.

At the end of the week, as darkness settles in on Friday evening—and with it, the peace of Shabbat—the long tables in the dining room are set with challah and grape juice, gefilte fish and salads. After prayer and Kiddush, the singing begins, softly at first, but then louder, more spirited. Before long, the sound of hundreds of Jewish children singing Shabbat melodies emanates through the otherwise silent Russian night. By the end of the evening, campers and staff are dancing on the benches, chanting in Russian: “I’m so proud to be a Jew!”

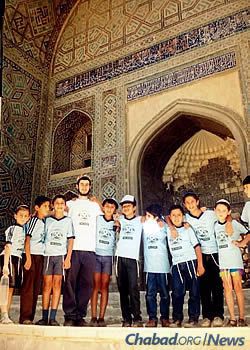

It’s a sight replicated in dozens of Gan Israel camps throughout Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and in the Caucuses and Baltics—one that the erstwhile leaders of the Young Pioneer Organization could never have imagined. It’s also one that continues to build upon the legacy of the very first Gan Israels in the Communist bloc, when small groups of American yeshivah students arrived in the decaying Soviet Union to change the face of Russian Jewry.

Forging a Bond

For years, the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based Lishkas Ezras Achim run by Chabad had arranged for Chassidic couples, yeshivah students and others to travel to the Soviet Union under the guise of tourism, laden with tefillin, mezuzahs and Jewish books to distribute to local Jews. Through the 1980s, their travel was closely monitored by authorities and limited to the cities they were given permission to visit, mainly Moscow.

“Everything Chabad was doing in Russia then was top-secret,” recalls Rabbi Levi Raices, today a Chabad emissary in Kharkov, Ukraine. “People who went in the early ’80s didn’t tell anyone about their trip until after they returned.”

With the expansion of rights created by Perestroika, the movement of Jews from abroad became freer as Jewish activities emerged from underground. Chabad yeshivah students began spending months-long shifts in the country, helping to reinforce the skeletal remnants of Jewish life that had survived the harshest years of oppression and operated out of the Moscow’s little wooden Lubavitch synagogue, Marina Roscha.

When summer of 1990 approached, the leadership of Ezras Achim began organizing what would be the Soviet Union’s first Jewish overnight camp for children, Camp Gan Israel. Rabbi Levi Heber, today a renowned mohel in the New York area, had been a camp counselor before, so when the opportunity to travel to the Soviet Union came—his father, Rabbi Shmuel Heber, was active in Ezras Achim—he jumped on it.

“I gathered a group of seven yeshivah students to serve as counselors,” says Heber. “Before camp, we all passed by the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] for dollars and a blessing for success.”

In August, the group disembarked in Moscow, just a few weeks prior to the arrival of Chabad’s first permanent emissaries to the Soviet Union—Rabbi Berel Lazar to Moscow; Rabbi Shmuel Kaminezki to Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine; and Rabbi Moshe Moskovitz to Kharkov, Ukraine. The circumstances that met them were, to hear it from him, less than ideal.

“The first year was very primitive; there were no flush toilets, no showers. Camp was held in a school building on the outskirts of Moscow that was not designed for that,” he recalls.

Beyond the lack of adequate facilities, the American counselors had no common language with their 100 Russian-speaking campers.

“Here was a group of Americans without any language, in what was to us a Third World country with very limited resources, and our job was to give these kids a wonderful summer experience while instilling within them the values of Judaism they had never been exposed to before,” explains Heber, who was 19 at the time. “Yet by the end of the summer, we were all singing together, benching [Yiddish for grace after meals] together and forging an amazing bond with these boys. It was truly miraculous.”

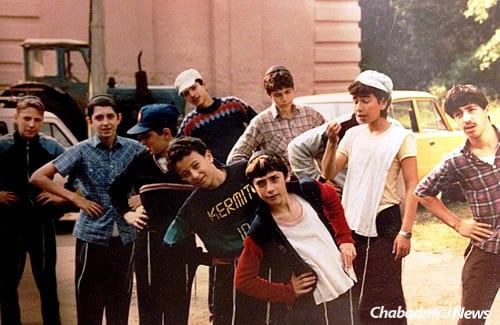

Midway through camp, Raices joined the crew. With the Communist economy in shambles, he saw empty stores and long lines to procure basic goods like bread and milk. The American dollar was so prized that the yeshivah students found themselves wealthy relative to the poverty surrounding them, even though there was almost nothing to buy.

What truly stayed in his mind, however, was the burgeoning Jewish pride he saw—boys with little Jewish knowledge now happily enveloped in an authentic Jewish experience.

“One kid had a trumpet,” says Raices. “When we took camp on trips, he used to blast ‘Haveinu Shalom Aleichem’ out the bus window. For them, expressing their Jewishness was totally new, and many were afraid. He didn’t care.”

The rag-tag team of spirited American yeshivah students left an indelible mark on their young campers, creating the Russian Camp Gan Israel model in use today.

‘Covenant of Abraham’

If the Soviet Union’s economic model was a failure, their efforts to obliterate millennia-old practices of the Jewish faith certainly were not. Members of the older generation remembered bits and pieces of their heritage, but some cornerstones of Jewish practice—like brit milah, circumcision—had almost disappeared.

While not explicitly banned, Russian Jews were intimidated into not circumcising their children, with Communist Party members—required by party rules to be atheist—facing expulsion, which inevitably led to social consequences and job loss. Grown Jewish men seeking to be circumcised found themselves at an even greater risk; adult circumcisions remained dangerous until the mid-1980s. An adult brit could lead to prison time for the mohel on charges similar to “operating without a surgical license” and for the adult for “self-mutilation.” It meant that a vast majority of Soviet-born Jewish men had never entered into the covenant of Abraham.

Scattered around the Soviet Union, however, were a handful of older Jews who continued to perform circumcisions under the cover of secrecy. Two of them were Chabad Chassidim Reb Mottel Lifshitz (warmly known as Reb Mottel der Shoichet for his work as a ritual slaughterer) and Reb Avraham Genin, both stalwarts of Moscow’s underground Jewish community. Reb Mottel was the city’s primary mohel for newborn babies, while Reb Avraham gathered funds and made the arrangements needed for an adult brit to take place, performing them himself with assistance from a surgeon.

Heber, who heads the International Bris Association and has thousands of circumcisions to his credit, cites his first summer at camp as the inspiration for his career. Towards the end of the first session, a group of seven boys expressed their wish to be circumcised. Dealing directly with Genin, the American counselors arranged for the circumcisions to take place at the anonymous Moscow apartment from which he operated.

Although by 1988 circumcisions were taking place openly in the Soviet Union, the sudden internal collapse of Soviet power meant that many of the older Chassidim, such as Genin, often continued to operate as they always had—underground.

“We snuck into the two-room apartment one by one,” recalls Heber. “We were met by Reb Avraham and the doctor he worked with. The bris was performed on the dining-room table, while the rest of the boys waited in the next room.”

The equipment was old, the anesthetic weak and the stitches coarse. From the moment the procedure began until its end, the campers screamed in pain. “We thought we’d gone too far,” remembers Heber. “The other boys were in the next room, and there was no way they didn’t hear the first boy’s cries.”

The brit wasn’t exceptional. It was simply how circumcisions had always been done in the Soviet Union: secretly and without proper medication.

To the staff’s surprise, when the first camper’s turn was over, the next boy opened the door and walked in.

“They were ready to endure it with true self-sacrifice because they knew how important it was,” says Heber. “Standing there, I felt there had to be a better way to do it, so the next year I came to camp prepared with more equipment. I became a mohel because of what I saw in that Moscow apartment.”

In the years since, thousands of Jewish boys have been circumcised at Gan Israel camps in the former Soviet Union, usually on a designated brit day when a mohel comes, and in a far safer and cleaner environment. (A new bris center opened just last month in Moscow in the Rambam Medical Center, part of the Shaare Zedek Jewish Center for Chesed, in the Marina Roscha neighborhood.) These days, Heber notes, he often circumcises the sons of his campers from Gan Israel Moscow, many of whom live in New York or elsewhere around the globe.

The War That Wasn’t

The next year, Gan Israel opened on proper camp grounds and was joined by sister camps in Kiev, Dnepropetrovsk and Kharkov. That summer, girls’ camps opened for the first time as well, staffed by young Chabad women flown in from the United States.

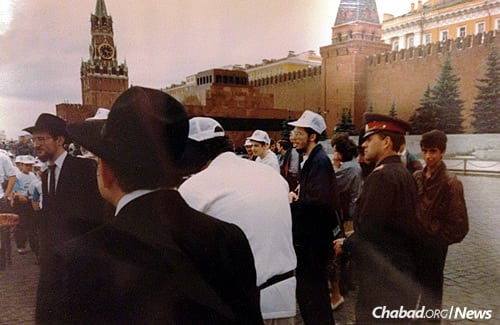

“In August of ’91, we took the whole camp to Red Square,” recalls Rabbi Dan Rodkin, a Moscow native who had recently become religious, and is now director of Shaloh House Jewish Day School in Boston. “We lined up right in front of the Kremlin, and said the 12 pesukim [Torah passages] proudly with everyone staring at us. A few days later, communism fell.”

On Aug. 19, hardline Communists made a last-ditch effort to save the dying Soviet empire by executing a coup. With tanks rolling through Red Square and memories of the Soviet Union’s past aggressive actions in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, no one knew what to expect. Foreigners streamed out of the country, and many Jewish organizations closed their doors.

“We thought it was going to go back to the way it was before,” says Rodkin. “It was a very scary time.”

Raices was head counselor at Gan Israel Dnepropetrovsk at the time and was awoken by the camp director. “All of you Americans have to leave now. There’s going to be a war!”

Glued to their shortwave radio, the group listened as BBC reported breaking developments from Moscow. Barricades had been set up, civilians killed. They tried phoning through to Chabad in Moscow, and when they finally got through, they had their answer: The Rebbe had given a blessing that everyone would be safe, and they should stay and continue their work. So that’s what they did.

In fact, all of Chabad’s activities in the crumbling Soviet Union continued unabated, and in Moscow, where Heber remembers successfully convincing parents that their children were safer in camp than in the city itself, Gan Israel’s session came to a happy conclusion the day the coup ended.

“A bus full of children had to wait on the highway back into Moscow for 90 minutes extra, and parents started to get worried,” recalls Rodkin, who was one of only two native Russian speakers working as a counselor that summer. “Later, we found out the delay was caused by the tanks leaving Moscow. The putsch [attempted coup] was over, and the Soviet Union dead.”

‘The Greatest Effect on Me’

It was the lively, daring spirit the American counselors brought with them in those heady early days that lives on in Gan Israel. The Russian campers were used to rigid regulations that were part and parcel of the educational methods in that area of the world. Their conception of Judaism and learning was flipped upside down when they encountered the authentic and warm Jewish “brothers” from across the ocean.

“I was older already, and a staff member, but the American counselors made a huge impression. It was mind-blowing,” says Rodkin, who also directs Camp Gan Israel in Brighton, Mass., and where some of his former campers from Moscow who live in the Boston area send their own children today.

Rabbi Moshe Baruch Beynish is a prominent educator and Chabad emissary living in Moscow. His path began at Gan Israel Kharkov, where he was sent at age 15 by his father in 1994. It was there that he first began to delve into his heritage, and where he began to keep the laws of kashrut and Shabbat, and received his Jewish name.

“I wasn’t settled in camp until Shabbat came,” he says. “That changed me. The singing, dancing, the farbrengen until the early hours of the morning … it had the greatest effect on me. I’ve kept Shabbat since then.”

Beynish also spent every subsequent summer until 2014 at a Gan Israel, either as a camper, counselor or, after his marriage, camp director of Gan Israel Moscow. He remains very active in camp there, creating its educational curriculum and much of its programming.

“Russian-speaking yeshivah students are the staff at camp now,” says Beynish. “But we couldn’t have done that without the example set for many years by the Americans. The Americans all cared for camp; they thought about it the whole year. They raised money to bring candies and prizes to camp; they didn’t expect anything to be handed to them. They came to Russia to give over whatever they could to the campers. Our staff were campers back then, so they know what that looks like and can give it over to their campers.”

Not all camps in the former Soviet Union are staffed by locals. Gan Israel Yeka in Ukraine (short for Yekatrinoslav, former name of Dnepropetrovsk, the Rebbe’s home city) is organized and funded by a small group of dedicated American yeshivah students working hand in hand with Chabad emissaries on the ground. The fundraising is done mostly through social media, and the dedication of the staff directly correlates to the phenomenal growth the camp has seen in recent years. This summer, they opened a girls’ division in conjunction with Chabad of Odessa.

“Ultimately,” says Heber, reflecting on the five summers he spent in Moscow, “we thought we were going to Russia to inspire the children there. But in seeing and interacting and building relationships with them—many of which have lasted until today—it was we who were inspired. You can’t witness pure Jewish souls yearning for more and not be.”

To find a Jewish camp near you, visit the Camp Gan Israel directory here.

The first article in the summer-camp series, “Deaf Boys and Girls to Experience Summer Camp Steeped in Judaism,” can be viewed here.

The second article in the summer-camp series, “Bigger and Better Than Ever: California’s Camp Gan Yisroel West,” can be viewed here.

Join the Discussion