The third in a series of three articles on Jewish life in Hungary.

Zsófi Steiner remembers attending High Holiday services in the 1990s in the little rundown synagogue in Budapest, Hungary, where her family had frequented for generations.

“There were only old men and women; my sisters and I were the only children there,” she recalls. “My great-grandfather, Aaron Glazer, had been the gabbai (communal officer) for many years there. When he passed away, his younger brother Jakob took over. My father celebrated his bar mitzvah there and had many childhood memories of when the synagogue had been full of life. For us, it was a strange and scary place.”

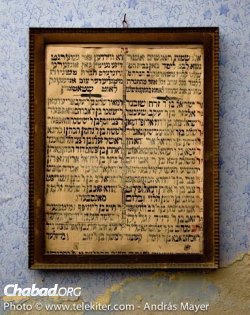

The synagogue had been founded in Jewish Budapest’s prewar heyday by poor but pious peddlers, who plied their wares in the Teleki Square marketplace. It was known as the Chorkover Kloyz (prayerhouse), as it was apparently frequented by adherents of the Chortkover Chassidic dynasty. Today, it is commonly referred to as the Teleki Square Synagogue.

During the Communist era, as many of the religious Jews who had survived the Holocaust fled the country or died, attendance slowly dwindled. Steiner says that because even talking about synagogue attendance was dangerous, family members would cryptically speak of visiting “22”—a code word for the synagogue at 22 Teleki Square.

Eventually, the synagogue was reduced to holding weekly services, often without a minyan, the quorum of 10 men needed to hold full communal prayer. Also, the “blue room”—named for its distinctive blue Star of David wall print, which had served as a women’s section—had become a default a storage room, full of decaying furniture and prayerbooks from defunct area synagogues.

‘Atmosphere Was Energizing’

As a young teen, following the lead of her older sister, Steiner began attending services and other events at the Sász Chevra Chabad Lubavitch synagogue, which had become a meeting place for young people and a center of Jewish life.

The synagogue was home to the Pesti Jesiva, an institution for advanced Torah studies with a core of students from the United States and Israel, who were joined by young Hungarian Jews.

But it was more than an academic institution. Friday nights at the synagogue became a magnet for young Jews, where spirited prayers were followed by a communal meal for between 50 and 100 people, crammed into the women’s gallery of the 120-year-old synagogue.

Many of the attendees were Israelis attracted to Hungary’s medical schools, but most were locals like the Steiner sisters, both of whom had begun observing Shabbat, keeping kosher and taking on full Jewish lifestyles as a result of their connection to Chabad.

“It was fun to be there,” says Steiner. “There was a great group of young Jewish people who, like ourselves, were exploring Judaism, and the atmosphere was so energizing.”

In 2002, Rabbi Sholom and Devorah Leah Hurwitz came to Hungary, where the South African-born rabbi became rosh yeshivah (dean of studies) at the Pesti Jesiva.

In the winter of 2006, Jakob Glaser passed away, and it became apparent that the Teleki synagogue was on its last legs. He was the last of the old men who had filled its pews for decades. There were barely half-a-dozen younger men coming every week. Determined to do something to perpetuate his legacy, the decision was made to make a final push to keep the synagogue going for as long as possible.

Meanwhile, Steiner married and moved into an apartment near Teleki Square. Her husband, Avi Kovacs, who was born in Budapest and had studied at the Chabad yeshivah in Migdal HaEmek, Israel, attended regularly in support of the endeavor. Sometimes, they gathered a minyan; more often, they could not.

‘A Cohesive Prayer Group’

Around that time, Hurwitz became rabbi of the synagogue.

“There was not much of a community when I came,” he says. “When we were praying, the room was silent. Many of the people came to support the synagogue, but did not yet know how to respond to the communal prayers. When my children became old enough to respond ‘Amen’ at the proper times, others joined them, and slowly, we grew into a cohesive prayer group.”

“We are a small synagogue with room to comfortably seat maybe 40 people, but we are a warm and welcoming congregation, so when someone comes once, we know we are probably going to see them again … and again.”

New members eventually trickled in, and waiting for a Shabbat morning minyan has become rarer. All in all, Hurwitz says hundreds of people now identify with the congregation, with 100 attending the synagogue’s Passover seder and even more at other events.

A sign of the synagogue’s vitality is that the “blue room” was recently renovated to become an all-purpose space where the congregants sit down to a full Shabbat meal every week after services. Much of the growth can be credited to the perseverance and dedication of Gábor and András Mayer, two brothers Steiner describes as the cornerstones of the community.

The mother of three small children, Steiner doesn’t often get out to the synagogue. But she finds it “quite emotional” that her husband takes her children to pray in the same place where her father and grandfather went when they were young.

“This past Rosh Hashanah,” Steiner recalls, “I came to synagogue after not having been there in several months, and the place was packed with people I had never seen before. I turned to my husband and asked, ‘What are all these strangers doing here?’ He replied, ‘What do you mean? They’re here every Shabbat.’ ”

Join the Discussion