A much-needed increase in the number of rabbis in fatigues may soon become a reality in the United States.

On Jan. 22, the Department of Defense issued a directive easing rules on beards and other displays of religious beliefs for military personnel in all branches of the armed forces. While special allowances have been made in rare cases in the past, the new directive gives wider leeway, especially for the existence of facial hair.

The military can now only deny the expression of “sincerely held belief” if it is judged to “have an adverse impact on military readiness, unit cohesion, and good order and discipline.”

With a sorely felt shortage of Jewish chaplains throughout the military, the rule change is expected to pave the way for the enlistment of bearded rabbis as military chaplains, a near impossible goal under the previously strict grooming code. The rule change will also affect Sikhs, Muslims and members of other religion groups, encompassing beards, turbans and other forms of religious expression.

The change in policy was welcomed by both Jewish military chaplains and lay leaders.

Rabbi Mendy Katz, director of prison and military outreach at the Aleph Institute—a Florida-based, Chabad-affiliated organization that provides social services and Jewish resources to military personnel and their families—explains that the directive has been eagerly awaited.

“We at Aleph have been trying for years to get the military to approve rabbis with beards across the board,” he says. “This has been a long time in coming, and it will do a lot to help the Jews who are serving our country in the military.”

The new regulation serves to further push a military establishment that is traditionally averse to change. In 2010, Chabad-Lubavitch Rabbi Mendy Stern, who had been denied a commission in the U.S. Army Chaplaincy Corps because of his beard, filed a federal lawsuit against the Army with the help of the Aleph Institute, claiming his constitutional rights to religious freedom and equal protection under the law had been violated. After a year-long battle, the Army ultimately settled, allowing him a one-time exception.

Stern is now a captain on active duty, stationed at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri.

“We live in a great country where religious freedom is respected,” adds Katz. “It may be hard for an institution like the military to make changes, but these are changes that must be made.”

He believes that the new rules will usher in an era of more Orthodox—and specifically, Chabad—rabbis enlisting in the military as chaplains. “Rabbi Stern is a very successful chaplain, and there is a great opportunity for many more,” he says.

‘Major Breakthrough’

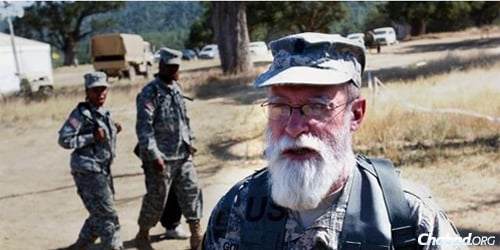

Stern is not the only rabbi to have received a special exemption for his nonconforming facial hair. Rabbi Jacob Goldstein is a colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve who has worn a beard since he joined in 1977.

“There was a lot of back-and-forth when I joined the Army; it eventually went all the way up to the chief of staff of the Army, Gen. Bernard Rogers,” recalls Goldstein. “He wrote a letter that said that as long as I remain a member of the Lubavitcher Chassidic group, I can keep my beard, and I’ve held on to that letter ever since. After he left, they got really tight about the regulation, and it stayed that way for 30 years.”

Goldstein, who throughout his career has been deployed numerous times to combat zones, including Grenada, Iraq and Afghanistan, describes the new allowance as a “major breakthrough,” and points to the case of Mendy Stern as having been a significant step towards the eventual reversal of protocol banning facial hair.

“Before Mendy Stern there was no avenue to bust through, but that’s changing now,” he says. “There’s a real need for Jewish chaplains, and this is really going to give the military a better shake at getting them.”

While some have argued in the past that beards may be dangerous by getting in the way of properly affixing a gas mask, for example, Katz dismisses the claim by pointing to the Israeli military, where a beard is far from an unusual sight and where having one has not proved a conflict as part of active duty.

Goldstein agrees: “I’ve experienced the gas chamber [a military training exercise that simulates a gas attack using modified pepper spray], Mendy Stern has experienced it; we’ve never had any problems masking.”

Ultimately, explains Goldstein, the directive crystalizes the exception that Stern received into a military-wide regulation. “The Army lives in a world of Army regulation, as do the Navy, Air Force and Marines. So this is really big.”

‘Guarded Optimism’

Rabbi (Col.) Sanford Dresin is a retired Army chaplain who is the director of military programs at the Aleph Institute, as well as a chaplain endorser for the U.S. Department of Defense. It was Dresin who fought alongside Stern in his battle to join the Army—a fight he feels contributed greatly to last week’s development. While he welcomes the news and describes himself as “very happy” to hear it, Dresin also sounds a note of “guarded optimism.”

He explains that “while this Department of Defense directive provides instruction to the various branches, it is still up to them how they will implement this. So the question remains how they will go about this. If they want, they can still drag their feet and make it very difficult to prove that you’re sincere.

“My biggest concern remains the Marine Corps. They’ve said that they want to backtrack on allowing yarmulkas, so we have to see what happens.”

Still, Dresin says that if it’s true, “then I’m ecstatic about this. I want to see more young rabbis with beards, and I certainly want to see more Chabadniks join the military. Mendy Stern is doing a great job, and I hope to see good candidates step forward.

“It’s a wonderful opportunity for someone who wants to go on shlichus and who is also physically fit. This is not a desk job; you have to get out there with the soldiers. You spend a lot of time with your constituents in the field.”

The new directive was released as the Aleph Institute gears up to host its seventh annual Aleph Military Jewish Chaplain and Lay Leader Training Program at the Shul of Bal Harbour in Surfside, Fla., which begins on Feb. 6. The conference, which draws chaplains and lay leaders from across the spectrum of the U.S. military, will focus on its theme of “Training in Tactics and Strategy for Ministry in a Changing Military.” With the major shift in policy, the topic could not have been timelier.

“I want to see ultimately where this goes,” says Dresin. “We have to see how the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force go about this. It’s definitely raised the level of sensitivity within the military. They have been speaking about diversity; now we’ll see if they deliver.”

Join the Discussion