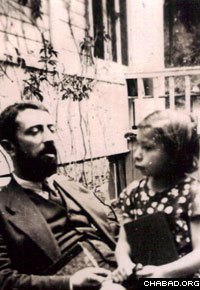

Life for Chana Sharfstein, a short, energetic woman who moved from Scandinavia to Boston only to experience the pain of her father being murdered at a young age, has not been easy. Shortly after her father’s passing, her mother passed away, leaving her an orphan in a foreign country. Her more than 70 years have been a near-constant struggle to understand why the Almighty would bestow such difficult circumstances on anyone.

Today, Sharfstein is far from bashful in discussing the twists and turns her life has taken. In the self-published Beyond the Dollar Line, a new volume available for purchase from the Kehot Publication Society, the publishing arm of Chabad-Lubavitch, she lays bare her philosophy of life, much of it gleaned from guidance given her by the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. Over the course of 244 pages, she shares a multitude of stories, excerpts of conversations and correspondence, describing almost poetically how they continue to guide her more than 16 years after the Jewish leader’s passing.

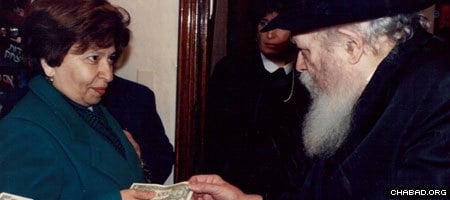

“Many people may know the Rebbe from the dollar line,” she says, referring to the hundreds of thousands of people who in the late 1980s and early 1990s would wait in line on Sunday mornings to share a word with the Rebbe and receive a blessing and a dollar bill whose value would then be given to charity. “This book goes beyond the dollar line. It examines personal experiences in my life and how I have applied them to my day-to-day activities.”

Known throughout her Crown Heights neighborhood in Brooklyn, N.Y., and throughout the Jewish world as an author, public speaker, educator and tour guide, Sharfstein has inspired countless women throughout the years. More often than not, the advice she offers has its roots in various teachings from and interaction with the Rebbe.

One incident she explores in the book centers around an offer she received to retire from teaching at a public school.

“Without much thought,” she writes, “I made a hasty decision [to retire]. I often thought that retirement would be wonderful.”

Shortly afterwards, she remembered with dread a conversation she had with the Rebbe many years earlier: In one of her audiences with him, the Rebbe asked how Sharfstein’s uncle, a rabbi in New Jersey, was doing. She responded that he had just retired.

The Rebbe shook his head. “Retired. What does that mean?”

“Situations may arise in life that necessitate changes,” the Rebbe, who would go on to suggest that the uncle move to New York and use his talents to further contribute to the Jewish world, told Sharfstein. “One must then make the appropriate adjustments. But retirement? Never!”

When Sharfstein remembered this exchange, she writes, she realized that she needed to find something constructive to occupy herself. She began giving classes at a local school and became a guide at the Jewish Heritage Museum in Manhattan.

Today, she’s also a guide at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and is working on several writing project.

Innocent to Bewildered

In another vignette, Sharfstein writes of some comments the Rebbe had to a draft of an article she wrote about encouraging other Jewish women to light Shabbat and holiday candles. In the article, she presented stories of women who had at first felt that it was “impossible” to commit to lighting candles each week.

The Rebbe, however, changed the word “impossible” to “very difficult.”

“Something that is viewed as impossible blocks change,” Sharfstein concludes in the book. But “very difficult means a challenge that can be overcome.”

A masterful storyteller, Sharfstein writes freely of her emotions and opinions. She retains a positive outlook throughout, discovering the good in every moment, in every human being she encounters during a difficult life.

“One day, I was an innocent, carefree student,” she writes, “the next, a devastated, bewildered young adult. There was an abrupt change from childhood into the ugly, gruesome world of adult reality. … Early one winter evening, just as the New Year began, my father lost his life at the hand of unknown assailants, and our lives were forever changed.”

A few months later her mother, Zlata, decided to go to a private audience with the Rebbe. Sharfstein accompanied her; it would be her first time meeting the Rebbe.

“My mother was visibly distressed,” she writes. “She was overwhelmed by the loss, the strange language and the newness of the country.”

She then goes on to describe the audience:

“My mother was crying softly while I glanced at the Rebbe. He looked at us with great compassion and concern: He had known my father well, and been involved with us in the aftermath of the tragedy. Then he smiled gently and invited us to sit down. He seemed so human, so warm, I immediately felt as ease. He spoke to my mother for a length of time, of her plans for the future, about her daily activities, about my father, and everything of concern to our life.”

The Rebbe turned to Sharfstein and asked about her future plans, her interests and concerns.

“He seemed so genuinely interested in everything I said,” writes Sharfstein. “From his responses and interjections, I knew he was listening carefully to everything. I seemed so comfortable and at ease, as if he were a family member, someone I had known all my life.”

Within a five year period, Sharfstein lost her father, mother and mother-in-law. Her father-in-law passed away before she was married. This had a great effect on the young women in her early 20s.

She once wrote an emotional letter to the Rebbe describing how she was alone.

“I was the youngest child in my family,” she writes in the book, “and never envisioned that in America my children would grow up without grandparents, just like me. But I had grown up in Scandinavia, in the Hitler era.”

“All religious people, even non-Jews,” the Rebbe wrote back to her, “believe that the Creator of the World is infinite and incomprehensible. … Obviously, it is impossible for a human being whose intellect, as all his other powers, is limited, to understand the ways of G‑d. … Indeed, it is not surprising that he does not understand G‑d’s ways, as mentioned above; it would be rather surprising if he did understand the infinite ways and reasons of G‑d.”

The Rebbe then described the journey of a soul.

“In no way can [the soul be] affected by the death and disintegration of the physical body,” he explained. “The truth is that when the physical body ceases to function, the soul continues its existence, not only as before, but even on a higher level, inasmuch as it is no longer handicapped by the restraints of its physical frame.”

From there, the Rebbe expounded on a family’s connection to the souls of loved ones.

“The general attachment between close relatives during life on this earth is surely not a physical attachment by the respective physical bodies of the relatives,” he wrote. “Every action on the part of a person in relation to a beloved person, and the desire to benefit that person, is not directed towards pleasing his physical body, his bones and tissue, for it is spiritual pleasure that one is concerned with.

“It is clear that even after the physical body has disintegrated and disappeared from view,” the Rebbe concluded, “it is still possible to bring joy and benefit to the soul. … All the things which had previously brought joy and pleasure to one’s parents will continue to do so even after they are physically no longer here.”

For many years, the extremely personal letter has motivated Sharfstein. She decided to publish it in the book in the hope that it would motivate others.

Other chapters describe encounters with the Rebbe, her parents, people she adopted as family, and her travels to Chabad-Lubavitch centers across the globe. She describes how her life is just one long journey of finding the hand of G‑d in every moment.

“Should life every present us with any real problems, G‑d forbid, we quickly grow up,” she surmises. “We learn to see the true, more important aspects of life; our feelings and judgments run deeper. If someone we love falls ill, G‑d forbid, our only thought of happiness is his recovery. Forgotten is any thought of buying things, going places, or seeking empty amusement. Our desires are elemental and basic, involving the ever-present, taken-for-granted blessings of daily life.

“Happiness is the ability to be thankful. It means being contented with one’s lot, and making the best of things. Permanent happiness, the genuine, lasting kind, can only exist when one learns to fully accept life as it is, with its blessings and problems.”

Join the Discussion