The cantonists were Jewish boys in the Russian Empire who were forcibly taken to camps (“cantons”) where they were trained to become soldiers in the Tsar’s army between 1827 and the end of the 1850s. Often snatched as young as six years old, they became soldiers when they turned 18 and were then made to serve as long as 25 additional years. Cut off from their families and communities, the boys were under tremendous pressure to abandon their Judaism, and many displayed heroic devotion to the faith of their ancestors.

The Missing Branch of the Family Tree

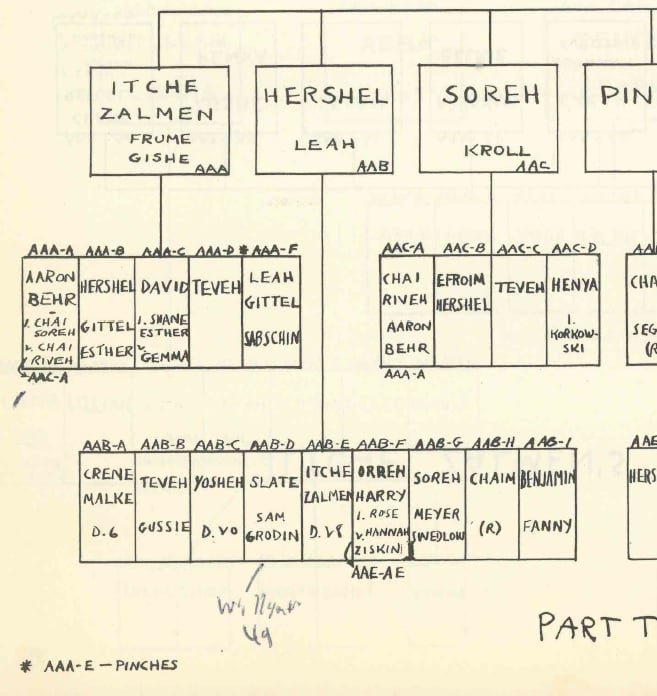

Leafing through an old family tree released around 70 years ago, I noticed a short note next to someone I had never heard of: My great-great-great-great-great uncle, Pinchas Posner (Pevzner).

On the branch of the tree where his nuclear family appears, Pichas’s name was originally not included alongside his five siblings (one of whom is my direct ancestor, Aharon Ber). There is just a small asterisk that points the reader to the bottom of the page where Pinchas’s name was added in small letters.

In the introduction to the family tree, we are told that Pinchas was taken to the Russian army at the age of six and that some of the elder members of the family did not deem him worthy of being included in the book, as he had “left the family.”

Unfortunately, Pinchas was far from unique.

Pinchas was a “cantonist,” a Jewish boy who was forcibly taken to a military school (“canton”), where he was not given kosher food or otherwise allowed to live as a Jew. After the boys turned 18, they were drafted into the military.

Originally a 25-year term, the military service was subsequently diminished to 18 and then 14 years. Meaning that boys like Uncle Pinchas could have been robbed of more than 30 years of life.

The era of the Jewish cantonists began in 1827 when Jewish children, as well as Jewish adults, were forcibly taken to cantons, military schools, which had previously served primarily the children of Russian soldiers. While some were stationed close to the existing Jewish communities in White Russia, where our family lived, others were stationed in far-off Siberia, virtually cut off from home and hearth. Yet even there, many of the boys clung to the faith of their childhood, determined to observe Judaism to the best of their meager knowledge and abilities.

From Home to Hell

The boys were selected by Jewish community (kahal) officials, who were required to furnish a specific quota of conscripts. Since the well-connected could often do whatever it took to protect their children, it was typically the sons of poor families, widows, and others on the margins who were taken.

This placed tremendous pressure on the leaders, who were often faced with the terrible choice of determining whom to send. Pinchas’s great-grandfather Berel, the earliest known ancestor of our family, was one such leader, who sent both Jewish and non-Jewish boys to the draft in equal proportions. This so angered the non-Jewish peasants, who wanted only Jewish boys to be drafted, that they doused his clothing in alcohol and set him aflame.

In many places, roving kidnappers (khappers in Yiddish) would take children off the streets and furnish them to the recruiting authorities at the behest of kahals desperate to fill their quotas while protecting their own children. As could be expected, these men were reviled by their fellow Jews.

Their efforts were countered by brave communal activists. Loosely coordinated by Rabbi Menachem Mendel—the third Rebbe of Chabad—one such group of activists worked in utter secrecy and used any means possible to wrest the children from the hands of the khappers, including bribery and falsification of death certificates.

The trip from home to the canton was often fraught with danger, with boys suffering from hunger, exposure, illness, and exhaustion even before they arrived at their battalions.

Pressure to Convert

Life in the cantons was brutal and the children were habitually starved. Treatment for illness included beatings, and the mortality rate was high (and appeared to be even higher among the non-Jewish children).

Under these conditions, the boys were subjected to extreme pressure to abandon Judaism, from military brass and clergy who offered financial incentives (25 rubles by order of Tsar Nicolas I himself), promotions, and breaks from incessant beatings in exchange for converting. The campaign to convert as many of the boys to Russian Orthodoxy as possible was the work of the Tsar, who micromanaged the project, demanding frequent reports on how many boys had been converted, rewarding priests responsible for large numbers of converts and berating those who fell behind.

Yet despite the immense pressure and suffering that was their lot, the majority of the cantonists maintained their Jewish identity, even though they often lacked basic knowledge of Judaism since they had been taken from home before they had a chance to learn to read Hebrew, celebrate the holidays, etc.

To Nicolas, the purpose of enlisting and converting the boys was pragmatic. He believed that an army would run better—as would his empire as a whole—if everyone worshiped, spoke, and believed in the same manner. And the best way to do that was to force them into the Russian military training machine, where they would become obedient, homogenous Russian subjects.

The repeated failure to convert the majority of recruits infuriated the Tsar, who tried firings, cash incentives, shaming and more to cajole the church and military establishments to ramp up the production of new Christians.

Strength to Resist

At times, the cantonists were assisted and encouraged by Jewish military men, who taught, guided and encouraged the boys. Jewish civilians working on base, such as cobblers and tailors, also provided support.

They were also allowed to attend synagogues and Jewish celebrations in nearby communities, which strengthened their resolve.

When Rabbi Menachem Mendel was in St. Petersburg to attend the rabbinical convention of 1843, he was granted a special permit to address the Jewish soldiers serving at the military fortress on the nearby island of Kronshtadt.

He was greeted by the waiting soldiers, who said to him: “Rebbe! We’ve been toiling all morning to prepare for your coming, polishing our buttons in your honor. Now it’s your turn to work hard: polish our souls, which have been dulled and coarsened by our many years of disconnection from Jewish life.”1

Upon graduation and their transition into the military proper, the Jewish soldiers proved to be as adept as their non-Jewish peers, if not more so, having well retained the various skills and tactics taught to them.

The Long-Term Effects

The sad era of the cantonists came to a gradual close following the 1855 death of Nicolas and the ascent of Alexander II, who canceled the draft of minors, although it continued through the end of the 1850s.

Scandalizing reports of forced conversions were surfacing, and converted cantonists (some of whom still wore tzitzit and prayed with hidden prayer books) were clamoring to openly return to the faith of their ancestors.

In 1858 an order was issued, forbidding the use of force in convincing Jewish cantonists to convert to Christianity.

But many issues persisted, with cantonists and former cantonists fighting for their right to use their proper Jewish names and otherwise live full Jewish lives. Some did so quietly, maintaining their official identity as Christians but living as Jews in private.

It took a full 15 years for Alexander to dismantle the cantonist institution, and it was not until 1905 that many aging cantonist converts finally gained official approval to reclaim their Jewish identity.

Forming New Communities

Following discharge, the cantonists who survived were granted certain rights, such as living in parts of the Russian empire normally off-limits to Jews. Thus, they formed the nucleus of the Jewish communities in places such as Finland (which is no longer part of Russia) and Siberia (where a Cantonists’ Synagogue still stands).

There is record of Rabbi Shmuel—the fourth Chabad Rebbe—encouraging Jews, who for whatever reason had rights to live in these areas—to use the opportunity to guide these sincere men, who so wanted to live Jewishly but had never had the chance to learn even the rudimentary elements of Jewish belief and practice.2

Even when allowed to return home, many cantonists did not want to, sensing that they would be shunned by communities who did not understand their experience and for whom their very existence was a mark of shame.

And whatever happened to Uncle Pinchas?

Family lore reports that he returned home but once to reproach his family for not having inculcated him with the Jewish knowledge and inspiration he would need to withstand the pressures placed upon him to convert.

And with that, he departed and was never seen again.

This essay is dedicated to the soul of Pinchas son of Yitzchak Zalman and Frumma Gisha. 3

Join the Discussion