Rabbi Shmuel Kaplan, chief Chabad-Lubavitch emissary to Maryland, has been airing a weekly program on Jewish.tv—titled “Discussions on Prayer” —since last December. His loyal and growing audience recently celebrated a significant milestone in such a relatively short time: The 100,000th class has now been attended online.

The rabbi, who is based in Baltimore, shares his personal reflections on prayer and what he aims to accomplish through the series.

Q: How did you first become interested in the art of prayer?

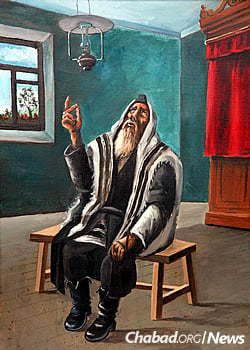

A: As a child learning at Lubavitch World Headquarters in Brooklyn—which we call 770—I remember observing Rabbi Uziel the Shochet [Chazanov]. He would pray with the yeshivah students. Standing in the center of the shul and speaking aloud, he would pronounce every word clearly and carefully. Every word was a word, deliberate and meaningful.

Another powerful memory was Rabbi Mordechai Groner, an elder Chassid who was raised in the Holy Land. One Rosh Hashanah, I sat next to him and observed him. He sat down to pray and began to cry. He didn’t stop crying until the very end. This touched me. It told me that there is more to prayer than just the mechanical repetition of words.

Throughout the years, I have merited to see many other Chassidim of the previous generation praying at length—baavodah in the Chabad parlance—and I realized that this is not something that just happens by itself. It’s clearly an art that is developed and perfected.

In the Torah, prayer is called avodah she’b’lev, (“service of the heart”); therefore, it should not be just lip service. It’s about putting your heart into it, but in order to feel, you need to know what you are feeling about.

When I was sent by the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] to Australia in 1969, I myself began to put more effort into my prayers, slowing down my pace, thinking about what I was saying, and praying with a bit more feeling and mindfulness.

The Rebbe would quote the Talmudic statement that during prayer, one stands as a servant before a king. Accordingly, the Rebbe said, it’s crucial to clear the mind of all other thoughts, even thoughts about helping others and spreading Jewish awareness and observance. It’s a time of intense inward focus.

The Rebbe also stressed that praying baavodah is not just something for an elite few, but something that is attainable and necessary for each and every Jewish person.

Q: What do you expect the video series to accomplish?

A: We live in a time when most people have lost the art of prayer. People know you come to shul and get out as quick as you can. Where I live in Maryland, we have a horse race—part of the Triple Crown—called the Preakness. I once mentioned that we need to learn from the Preakness how not to pray.

The horse is running through the race thinking how soon he can get to the finish line. When we pray, we need to focus on what we are saying and appreciate what it is saying to us.

Hebrew is not like English. English is rich with words, and there is a word to express every thought or nuance. Hebrew has far fewer words. Thus, each one is laden with much more meaning, and has multiple shades and layers of significance that can be unpacked and appreciated.

On the surface, it may be inscrutable. So when people read words and do not have the foggiest idea what they’re reading, they just think about getting to the end.

So the first step is actually to learn what we are saying at any given time of the services. Then, there is a need to understand the structure, how the service is built and how it progresses, and what each piece adds to the whole. Once you have some of that, it is possible to pray seriously since you are able to be engaged.

I have used the analogy of a walk through an elaborate botanical garden. You walk along and take in the delightful sights and aromas. However, every once in a while you also stop to inspect a particular flower or garden bed, and then just stand there and bask in its beauty. And so it should also be with davening.

Q: You’ve released the Siddur Illuminated by Chassidus. In what way is the class different from the siddur?

A: As the name suggests, the siddur specifically adds the Chassidic approach and interpretation of the prayers—and there is nary a Chassidic discourse that does not contain a commentary on prayer.

The video series, on the other hand, is one step more basic. It goes through each of the prayers, explaining the meaning and significance of every piece in a more classical sense. Of course, there is Chassidic teaching there as well, but it’s one facet among many. I like to say that the class is a potpourri culled from several dozen commentaries on prayer that I’ve collected.

Q: Is there a specific commentary that has influenced you more than others?

A: There are really so many. From the classic Abudraham from the 14th century to the Maharal in the 16th century to Rabbi Yaakov Emden from the 18th century—and really so many others—every commentary adds something and has left a unique mark on my approach.

Q: Do you have a message for readers?

A: Sure! Reading about prayer is nice, but you need to actually start praying, so buy the book, join the video classes and see how you can make your prayer into a meaningful experience.

Q: Who is all of this geared to—seasoned worshippers or those just starting out?

A: Beginners who have a familiarity with prayer can gain from them, though no prior knowledge is really necessary. On the other end of the spectrum, there is a fellow in my shul—he has his semichah and told me that has listened to every video.

It’s for anyone who wants to learn how to pray.