Introduction: Seeds of Conflict

The tzimtzum narrative is one of the central teachings of Rabbi Yitzchak Luria (Arizal), for whom the Lurianic school of Kabbalah is named. Tzimtzum, we have already discovered, does not describe an event that unfolded in time and space, but is rather a statement about the very fabric of reality, about the nature of G‑d’s relationship with the created realm.

Put simply, the tzimtzum narrative asserts that the divine self utterly transcends the role of creator. The process through which G‑d chooses to be manifest as creator, projecting our universe into being, actually represents a concealment of G‑d’s infinitely transcendent nature. Arizal’s account seems to imply that creation is the assertion of an imminent manifestation of divinity which expresses absolutely nothing of G‑d’s essential self.

Such abstract theosophical doctrines are anything but simple, and it is hardly surprising that the precise import of this assertion soon became an issue of debate. What began as a scholarly disagreement amongst various Mediterranean Kabbalists in theWhat began as a scholarly disagreement . . . became the nucleus of contention between the chassidim and their mitnagdic opponents in the second half of the next century. late 1600s became the nucleus of contention in an often explosive confrontation between the chassidim and their mitnagdic opponents in the second half of the next century.

The more literal reading of the tzimtzum narrative implies that the divine essence does not only transcend, but is completely absent from the creative process and the created realm. This face-value reading is referred to as tzimtzum ki-peshuto. But the narrative could also be interpreted to mean that the divine essence, in all its transcendence, remains fully present, and is only concealed by the creative process. This non-literal approach is referred to as tzimtzum she-lo ki-peshuto. For the chassidim, tzimtzum she-lo ki-peshuto cast the very nature and purpose of earthly existence in an entirely new light. But for their detractors, this brave new vision was dangerously seditious and even heretical.

A Mediterranean Affair

The first to articulate the non-literal interpretation was Rabbi Avraham Cohen de Herrera (or Airira, spelled אירירה or הירירה in Hebrew). Born in 1570 to a family of Spanish anusim, de Herrera travelled widely throughout Europe and represented the business and diplomatic interests of the Moroccan sultan. When the Spanish port of Cadiz was captured in 1596 by a joint force of English and Dutch troops, de Herrera was detained along with the city’s mayor and other hostages against a ransom of 120,000 ducats. He spent five years in the Tower of London before the Moroccan sultan arranged his release, and according to some accounts it was from this point on that de Herrera began to live openly as a Jew.1

It was in another historic port city, Ragusa (today Dubrovnik, on the Adriatic seacoast of Croatia), that Rabbi Avraham de Herrera met Rabbi Yisrael Sarug (סרוג or סרוק in Hebrew). Although it is unclear whether or not the latter was a direct disciple of Arizal, he devoted his entire life to the study of Arizal’s writings, and was largely responsible for the dissemination of his teachings throughout Europe. The writings of Rabbi Yisrael Sarug and his many students are often considered as a distinct branch of Lurianic Kabbalah, referred to as the Sarugian school (קבלת סרוג), and distinguished by a philosophical bent.

Shaar ha-Shamayim—originally written in Spanish as Puerta del Cielo—is a classic work of Sarugian Kabbalah,Shaar ha-Shamayim, originally written in Spanish as Puerta del Cielo . . . synthesized Arizal’s teachings with neo-Platonic rationalism. in which Rabbi Avraham de Herrera synthesized Arizal’s teachings with neo-Platonic rationalism.

Accordingly, Rabbi Avraham considered G‑d the ultimate non-contingent being, whose potency sustains all the contingencies of created reality. Divine non-contingency does not only mean that G‑d’s being is not dependent on any other being, but also that it is not bound by any conditions at all. Rabbi Avraham further reasoned that it is this non-contingent quality that leads to the concept of tzimtzum—the “removedness” of the divine self from the narrow role of creator—as a non-contingent G‑d necessarily transcends every category.

By this very line of reasoning, however, Rabbi Avraham also concluded that this “removal” cannot be an actual absence, but must rather be a concealment. The very non-contingent quality which entails the transcendence of tzimtzum, he argued, also entails that G‑d’s being must be extended throughout all categories of being. Just as G‑d cannot be defined by any category, so G‑d is not restricted from any category.

Here’s the crux of the argument in his own words:

The more complete the cause, the more it will transcend its effects and the more it will extend itself to them. Therefore, the blessed Infinite One will on the one hand be transcendent without limit, transcending all its effects—i.e., the creations, each of which, and all of which together, are finite—and on the other hand will extend itself to all of them. For not only is it their cause . . . it also passes through all of them, and fills them all, and it is all that they are . . . Each one of them, and all of them, are nothing aside from what they receive from it.2

In short, the unmitigated completeness of the divine self entails that it simultaneously transcends and The unmitigated completeness of the divine self entails that it simultaneously transcends and embraces all conceivable realities.embraces all conceivable realities.

The idea that transcendence and immanence are two sides of the same coin has a long history in Kabbalistic literature. The Zohar asserts that “the infinite manifestation of divinity extends upwards without end, and downwards without measure”;3 “transcends all worlds and fills all worlds.”4 But it was Rabbi Avraham Cohen de Herrera who first married this duality to Arizal’s concept of tzimtzum.

Despite these precedents, and despite the logical coherence of Rabbi Avraham’s argument, not everyone was convinced that the tzimtzum narrative should be understood in such abstract terms. Foremost amongst the dissenters was Rabbi Immanuel Ricchi (רפאל עמנואל חי ריקי), better known by the title of his most important work, Mishnat Chassidim.

Born in Ferrara, Italy, in 1688, Rabbi Immanuel first became acquainted with Kabbalah in that country, but resolved to travel to Safed, in the Holy Land, to immerse himself in its study. Two years after his arrival in 1718, an epidemic forced him to return to Europe. After an entanglement with pirates, he briefly took up a rabbinical post in Florence before moving to Livorno. There he engaged in commerce and study, and began to work on several volumes dealing with both Talmudic and Kabbalistic topics.5

In his Yosher Levav Rabbi Immanuel turned his attention to tzimtzum, and asserted his preference for a literal reading of Arizal’s narrative. Accordingly, he is of the opinion that G‑d’s essential self is literally removed from the realm in which the created beings exist. “One who cares for the honor of G‑d,” he argues, “must think of this tzimtzum in a literal sense, rather than reduce G‑d’s honor by thinking that the divine self is present even in lowly physical things, which are dishonorable and even despicable.”6

This argument is acknowledged by Rabbi Immanuel to be more emotional, or intuitive, than rational. Initially he does attempt to defend some of the philosophical objections to his position, but ultimately concludes that “such hidden things are not understood by us with our natural philosophical capacities.” “I accept this view,” he admitted, “not based on philosophical inquiry into the nature of G‑d’s being, but because it is more reconcilable to my heart that it be taken literally.”7 Rabbi Immanuel is simply unwilling to accept the idea that the transcendent essentiality of G‑d’s self is immanently present even within the crudest of physical things.

Rabbi Yosef Irgas (אירגס) was the rabbi of Livorno at the time, and no doubt was familiar with Rabbi Immanuel Ricchi’s position firsthand.8 His work Shomer Emunim was composed as a dialogue in which a Kabbalist helps a Talmudist to discern the conceptual depth so often concealed by the metaphoric obscurities of Kabbalistic literature.One who cares for the honor of G‑d . . . must think of this tzimtzum in a literal sense, rather than reduce G‑d’s honor. In a discussion of tzimtzum,9 the Kabbalist (named Yehoyada) offers a plethora of philosophical and textual proofs, conclusively demonstrating that Arizal never intended the tzimtzum narrative to be taken at all literally. As in so many other instances, he was simply borrowing the vivid language of the here and now to describe realities that actually bear no similarities to anything the human mind can visualize. Not very surprisingly, Yehoyada’s Talmudic interlocutor, Shaltiel, is convinced, and holds this up as an example of the “fundamental” mistakes that can be made by “those who read the books of the Kabbalists at face value, without deep thought and philosophical enquiry.”10

Although Rabbi Immanuel Ricchi failed to address the philosophical objections to his literal reading of the tzimtzum narrative, he did address some of the textual problems with more conviction. One example, which would come to the fore in subsequent incarnations of the debate, was the Zoharic statement that “there is no place empty of G‑d.”11 Being that Rabbi Immanuel opined that the created realm actually is empty of the divine self, he was forced to interpret this to mean that no place is empty of G‑d’s providence (hashgachah, in Hebrew). Accordingly, the divine essence is literally absent from the created realm, but various degrees of divine knowledge and supervision are yet extended throughout all existence.12

Between Absence and Concealment

To help draw the conceptual magnitude of this debate closer to our perception, let’s imagine the following (entirely fictitious) scenario:

Leonardo da Vinci, the paradigmatic Renaissance polymath, is in the midst of painting his all-time masterpiece. In one great work he intends to express a vision of all the vast complexity of his inner mind. The mysterious intersections of science, music, mathematics, art and philosophy will all be laid bare on a single canvas. In this painting, Leonardo seeks to communicate the very essence of his being, and he is entirely engrossed in this all-consuming task.

He has been at it since four o’clock in the morning, and now it is nearly five in the afternoon. Not having eaten the entire day, Leonardo begins to wane. Feeling tired and dizzy, he suddenly realizes that he is ravenously hungry. Tearing himself away from his very lifework, Leonardo spreads two slices of bread with cream cheese, and deftly slices a tomato into perfect rounds to make himself a sandwich. With a last flourish of the knife he divides the sandwich into two perfect halves; he grabs one half in his left hand and immediately returns to his painting—which in truth he never left. Even as he smeared the bread thickly with cheese, there was nothing in Leonardo’s world other than the unfinished portrayal of his deepest self.

After several more hours of intense activity, the masterpiece is complete; Leonardo collapses exhausted into bed and falls asleep. After a while, a child wanders into the studio, and gazes uncomprehendingly at the exhausted old man on the bed, the finished painting on the easel, and—on a stool beside it—the remaining half of Leonardo’s cream cheese and tomato sandwich.

Both the painting and the sandwich are the work of Leonardo da Vinci, but neither of them convey anything of Leonardo’s genius to our child observer. Leonardo is entirely absent from the sandwich, but all the vast breadth and creative depth of his persona is vested in the painting.All the child can surmise is that the old man is either a sandwich maker who paints, or a painter who makes sandwiches.

As far as the child is concerned, the sandwich and the painting are equally inadequate expressions of Leonardo’s transcendent genius. Yet the difference between these two objects is momentous. Although they were both made by Leonardo da Vinci, the sandwich is just a sandwich, while the painting embodies something of Leonardo’s very self. Leonardo is entirely absent from the sandwich, but all the vast breadth and creative depth of his persona is vested in the painting. It is only that the child is not equipped to see it.

With this analogy in mind, let us return to the distinction between tzimtzum ki-peshuto and tzimtzum she-lo ki-peshuto.

If the tzimtzum narrative is taken at face value (tzimtzum ki-peshuto), then the created reality is analogous to Leonardo’s sandwich; G‑d created the world, and very much cares about worldly events and human actions, but G‑d’s essential self is in no way embodied or invested in such goings-on. In the analogy, Leonardo was very hungry, and he really liked cream cheese; peanut butter and jelly really would not have gone down well at all. But none of these facts are in any way relevant to—or expressions of—Leonardo’s essential genius.If the tzimtzum narrative is taken at face value . . . the divine self remains entirely absent from the created realm even as divine supervision is exercised therein. In the analogue, the utter transcendence of the divine self remains entirely absent from the created realm even as divine supervision is exercised therein.

If, on the other hand, we interpret the tzimtzum narrative to mean that the essential assertion of the divine self is actually concealed within—rather than absent from—the creative process (tzimtzum she-lo ki-peshuto), then created reality is better compared to Leonardo’s masterpiece. The painting isn’t just something that Leonardo happens to have made: it is an external embodiment of all his vast genius, even if the observer can’t see it. In the analogue, the utter transcendence of the divine self is immanently present within all of created reality in an even more intimate sense, even if that presence isn’t discernible to the human eye.

Chassidim and Mitnagdim

Transported across Europe, and inserted into a deeply complex context of social and religious upheaval, the potent depth of this distinction became the seminal bone of contention in a controversy that tore entire communities asunder.

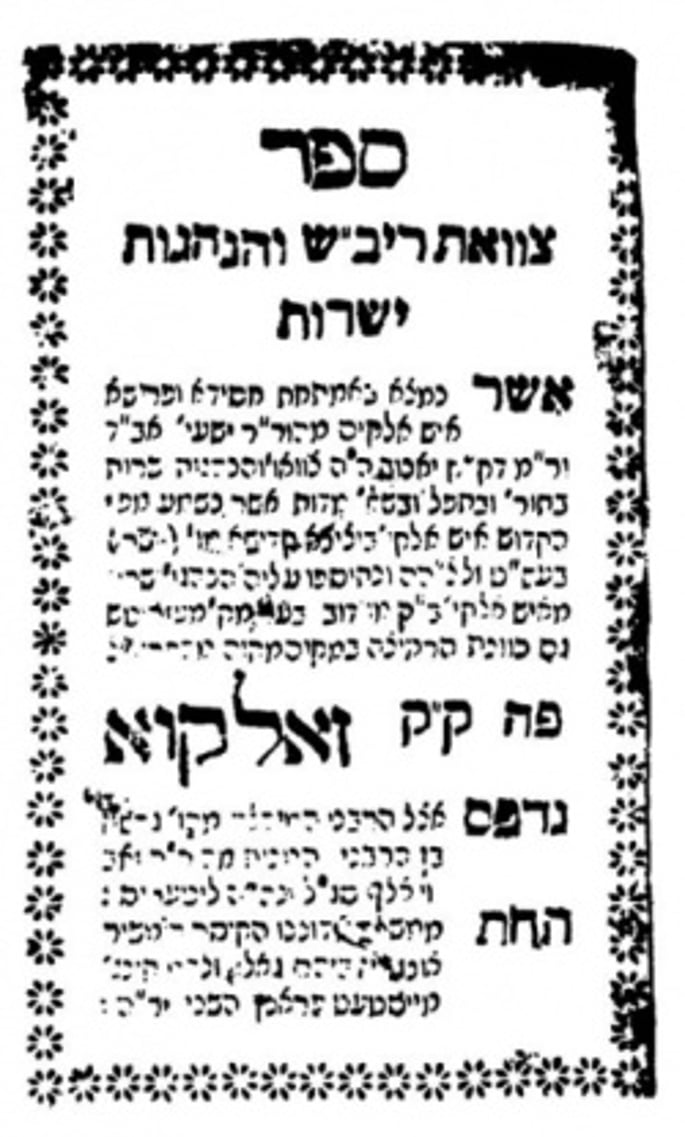

In the early 1790s a slim volume, compiled by an unknown author, was published in Zolkva (זאלקווא, today called Zhovkva), a small city in western Ukraine, bearing the title Tzavaat ha-Rivash.13 All of the teachings included in this text had already been published in earlier works, but this was the first such book whose title page bore so authoritative an appellation; Rivash is an acronym for Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem—the founder of the chassidic movement, who had passed away in 1760—and the appearance of Tzavaat ha-Rivash helped inspire a new assault against the spiritual heirs of its namesake. In the ensuing controversy, the debate regarding the tzimtzum narrative was placed front and center.

In a letter addressed to Paul I, emperor of Russia, a certain Avigdor ben Chaim later testified that it was he who convinced Rabbi Eliyahu, the famed Vilna Gaon, that the books of the chassidim contained “so many foolish and subversive views . . . and things that depart from the good way, that according to our law they must be burned in public.14 They brought this to fruition in Vilna, and commanded the public burning of the books of this cult in front of the synagogue.”15 Another letter, penned by representatives of the Vilna congregation, confirms that “the pietist [Rabbi Eliyahu] purged the [chassidic] cult from the holy congregation of Vilna so far as he was able, and also burned Tzavaat ha-Rivash in the presence of a large gathering . . .”16

The Vilna Gaon often figures in anti-chassidic literature as the movement’s most authoritative detractor; but there are few firsthand sources in which he himself chronicled his objections. Accusations that the chassidim are ignorant, subversive, unruly and immoral are also common, but rarely are more specific and substantive objections raised. An exception to both these rules is a public letter penned by the Gaon in 1797 in which he G‑d not only causes the existence of all created things but also passes through all of them, fills them all, and is all that they are.supplemented the usual diatribe with a theological critique that does indeed drive to the core of the Baal Shem Tov’s teachings.17

In the words of Rabbi Avraham Cohen de Herrera (cited above), G‑d not only causes the existence of all created things but “also passes through all of them, fills them all, and is all that they are.” Taking this notion to its logical conclusion, the Baal Shem Tov taught that even the most mundane things and actions carry the absolute significance of the divine self. This does not mean that all realities should be unconditionally embraced; on the contrary, such realities normally conceal the spark of divinity that lies at their core. But when we engage a given object or situation in the service of G‑d, the external concealment is stripped away and its true nature is drawn to the fore.

Accordingly, Tzavaat ha-Rivash interprets the verse “In all your ways know G‑d”18 as an instruction to utilize even the most mundane activities to make divine transcendence immanently manifest.19 A couple of pages later, this “major principle” is reiterated: “In everything that exists in the world there are holy sparks, there is nothing empty of the sparks, even wood and stones, and even all the actions that a person executes . . .”20

This last passage likely formed the basis of the Gaon’s accusation that the chassidim proclaim of every stick and every stone, “These are your gods, Israel!”, a phrase which is borrowed from the biblical episode of the golden calf,21 effectively equating chassidism with the worst example of public idolatry. “These evil evildoers,” the Gaon proclaimed, “have fabricated from their hearts a new law and a new Torah; their students who followed them have drunk it; and the name of heaven has been profaned by their hand.”22

A Seminal Schism

For the Gaon and his fellow mitnagdim, this wasn’t a mere theological quibble, but a frontal attack on the chassidic worldview.

The notion that G‑d is literally absent from the created realm (tzimtzum ki-peshuto) entails that the relationship between G‑d and man is marked by a hierarchical chasm that can be bridged only by quantitative degree. From this perspective, Holiness is not to be measured in terms of personal achievement, but by degrees of transparency to ubiquitous divinity.G‑d is qualitatively removed from the created realm; but by studying more Torah and accruing more mitzvot, a heightened degree of worthiness can be achieved. The chassidic concept of divine immanence (tzimtzum she-lo ki-peshuto) completely collapses that hierarchy. From this perspective, G‑d’s transcendent self is immanently concealed within all of created reality; via the path of Torah and mitzvot man can reveal the infinite quality of that intimacy even in the most mundane aspects of life. If used correctly, a single moment can be infused with eternal value.

From the chassidic point of view, neither the learned scholar nor the reclusive pietist can claim a monopoly on holiness. Man’s purpose, the Baal Shem Tov taught, is not to try and escape the clutches of earthly endeavor, achieving some more transcendent station. On the contrary, such mundane occupations as plying a trade, working the land or eating are to be transformed into vehicles for the revelation of divine immanence. Holiness is not to be measured in terms of personal achievement, but by degrees of transparency to ubiquitous divinity.

This brings us to another important axiom of the Baal Shem Tov’s teachings. The hallmarks of holiness are transparency, selflessness and humility; the measure of unholiness is egotism, self-obsession and arrogance. In the words of the Talmud, “Of the haughty one G‑d says, ‘He and I are unable to dwell together in the world.’”23 Selfishness most effectively obscures the immanent presence of the divine self.

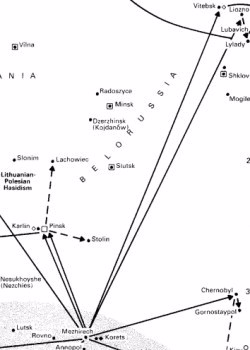

These ideas are powerful and empowering, and with the passing years they gained increasing momentum. The establishment of chassidic centers by such figures as Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk and Rabbi Aaron of Karlin in the mid-1760s marked the spread of chassidism from Poland to White Russia and the borders of Lithuania. Both were disciples of Rabbi DovBer, the Maggid of Mezeritch, who had become the most prominent exponent of chassidic teaching following the Baal Shem Tov’s passing, and it was through them and their contemporaries that chassidism became widespread as a popular movement. Other disciples of the Maggid who hailed from that general region included Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk, who had previously been a student of the Vilna Gaon,24 and Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi.25

Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk was a gifted scholar, a man of deep and powerful sentiment, and a charismatic leader. Upon returning from Mezeritch he established a following amongst young men of similar ability and temperament. These young men were captivated by the radical notion of divine immanence, and they strove to cultivate an ever deeper sense of humility and selflessness, combined with joy in the presence of G‑d. Their prayers were marked by deep fervor and rapturous joy, and in their most ecstatic moments they would turn somersaults in a head-over-heels gesture of utter self-effacement. To the followers of Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk, even the slightest hint of egotism was anathema, and they had little patience for scholars who took pride in their abilities and achievements.Their sole intention was to breathe new life into Jewish practice and learning by promoting an increased sense of divine omnipresence. Their sincere dedication, however, was soon overcome by an excess of zeal.26

To the followers of Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk, even the slightest hint of egotism was anathema, and they had little patience for scholars who took pride in their abilities and achievements. They reserved particular contempt for the rabbinic preachers who made their living by railing against the sins of the general Jewish populace, attempting to reduce their audiences to tears with threats of eternal punishment. In the eyes of these idealistic young scholars, the simple Jews—who observed what little they knew of the commandments conscientiously and selflessly—were to be praised, encouraged and empowered. Conversely, the rabbinic leaders who so condescendingly condoned their censure deserved to be toppled from their self-righteous pedestals.

These were subversive sentiments, and while the chassidim had no intention of undermining rabbinic authority, they did want to bring about a collective change of attitude. Such an effort could succeed unopposed only if it was conducted with due care and finesse. Unfortunately, however, such delicacy seems to have been the one thing that some of Rabbi Avraham’s followers lacked. Carried away by the emotive power of their convictions, they would sometimes exhibit their uninhibited rapture and self-effacement by dancing wildly in the streets. Organized opposition to the chassidic movement began as a Taking the notion of divine immanence to its furthest degree, the Baal Shem Tov taught that a spark of divinity even lies buried within a sinful act.direct response to their open display of contempt for certain rabbinic leaders.27

Taking the notion of divine immanence to its furthest degree, the Baal Shem Tov taught that a spark of divinity lies buried even within a sinful act. Never did he suggest that sin should be encouraged or even condoned, but he did affirm that sin created a unique opportunity to “return” (teshuvah) and develop a more intimate relationship with G‑d. The very passage in Tzavaat ha-Rivash which the Gaon attacked for proclaiming that a divine spark resides even in “wood and stones” continues to assert that “even in a sin that man commits there are sparks . . . and what are the sparks in a sin? Teshuvah!”28

Nothing warrants a sinful act; indeed, such an act drags a spark of the divine self into exile.29 But once committed, a sinful act must be harnessed to inspire a process of regret and return, culminating in an even deeper degree of subjugation to the divine will than could previously have been attained. Such a process of teshuvah reveals the divine spark that is buried even within sin, elevating it and redeeming them from exile.30 These ideas were drawn directly from the teachings of Arizal,31 but for the Vilna Gaon even his authority was not enough.32

The rise of chassidism in Eastern Europe coincided with the spread of antinomian cults under the leadership of Jacob Frank, who claimed to be the reincarnation of the false messiah Shabbetai Tzvi. Like Tzvi, Frank and his followers justified their open rejection of the Talmud and halachah—along with their engagement in adultery and other profane activities—by perverting the Lurianic doctrine that fallen sparks of divinity reside even in the lowest realms. In 1759, Frank and many of his followers had converted to Christianity.

The chassidim did not reject the Talmud, nor did they downplay the central importance of halachah. But their embrace of such a radical notion of divine immanence led the chassidic movement to be misrepresented and misunderstood as a new incarnation of the Sabbatean heresy. Nothing could have been further from the truth; the entire purpose of chassidism was to promote and perpetuate the service of G‑d through Torah study and mitzvah observance. But given the context of social and religious upheaval, the potent depth of this doctrine, combined with the indelicate exhibitionism of the Kalisk chassidim, was enough to raise the ire of the rabbinic leadership in Lithuania.33

In the spring of 1772 the foremost communities of Lithuania—including Brisk, Shklov and Brody—were led by Rabbi Eliyahu, the Vilna Gaon, in a spate of public denouncements and excommunications directed at the new chassidic “cult,” sometimes referred to as “the Karliners.” Much of the relevant documentation was collected and published that same year near the town of Brody.34 Copies were disseminated far and wide and were quickly snapped up, literally adding fuel to the fires of controversy. In an anti-chassidic letter dating from the spring of 1773 it is claimed that the pamphlet, titled Zemir Aritzim (which means “Slasher of Tyrants”), was publicly burned by chassidim in the town of Grodno.35

Providence and Its Ramifications

In the wake of these events Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk was taken to task by Rabbi DovBer, the Maggid of Mezeritch, who rebuked him for the undisciplined behavior of his disciples.36 But the utter refusal of the Vilna Gaon to enter into any kind of dialogue with the chassidic leadership cannot be put down to irreverent antics alone; ultimately, his deep suspicion had more to do with belief than behavior.

As we have already noted, in taking the tzimtzum narrative to mean that G‑d’s self was literally absent from the created realm, Rabbi Immanuel Ricchi was forced to interpret various statements implying divine omnipresence as referring to the omnipresence of divine providence (hashgachah. Accordingly, The notion of hashgachah is invoked in the context of tzimtzum to justify a literal understanding of divine transcendence that utterly removes the divine self from the created realm. the notion of hashgachah is invoked in the context of tzimtzum to justify a literal understanding of divine transcendence that utterly removes the divine self from the created realm. It is noteworthy that in several instances, quite isolated from his polemic against the chassidim, the Vilna Gaon too avoided interpreting such statements as references to the immanent presence of G‑d.37 In a more direct discussion of the nature of tzimtzum, he interprets it as a statement regarding the utter infinitude and inconceivability of the divine self. But here too the Gaon is careful to describe the “line” (kav) of divinity that is extended into the created realm as “an extremely limited superintendence.”38 While he did not read the tzimtzum narrative as an event that literally unfolded in time and space, he clearly did understand it to mean that G‑d’s transcendent self was literally removed from the limited domain of creation (tzimtzum ki-peshuto).39

The Gaon’s position as spelled out in the 1779 letter cited above seems unequivocal: the belief that divine transcendence is immanently present in the most mundane—and even profane—realities of the physical realm renders even the most inoffensive and scholarly chassid a complete heretic.

With the passing years, it increasingly fell upon Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (who lived first in Vitebsk and later in Liozna, and moved to Liadi only in the early 1800s) to lead the chassidim of White Russia and Lithuania and to bear the brunt of the mitnagdic attacks. Rabbi DovBer, the Maggid of Mezeritch, had passed away not long after the controversy started in earnest, and Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk and Rabbi Avraham of Kalisk had emigrated to the Holy Land in 1777.40

Rabbi Schneur Zalman was one of the youngest of the Maggid’s disciples, but stood out among them for his unique ability to channel profound aspects of faith and feeling through the rigid faculties of the rational mind. It was on this basis that he founded the Chabad school of chassidic thought and practice.41 True sentiment, he taught, must be informed by sense and sensibility. Rabbi Schneur Zalman was also an exceptional Talmudic scholar; the Maggid had charged him to compose a new code of Jewish law, seamlessly arbitrating between the different authorities, and combining clear rulings with concise explanations.42

From the very beginning, Rabbi Schneur Zalman sought to resolve the controversy through reasoned dialogue. In the winter of 1772 he had accompanied Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk to Vilna, but the Gaon had steadfastly refused to see them, going so far as to leave the city until they departed.43 In 1787 a second wave of intensified persecution was directed against Rabbi Schneur Zalman personally, and again he beseeched his detractors to allow him the opportunity to defend himself before recognized authorities who might arbitrate between them without bias. Let him explain his reservations against us regarding this belief . . . and I will follow after him . . . The two letters will be sent to all the wise men of Israel . . . and by the majority we shall rule. Not surprisingly, his request was ignored, and persecution of chassidim throughout the region continued unchecked.44

When the third wave of anti-chassidic agitation began in the early to mid-1790s, Rabbi Schneur Zalman repeated his earlier exhortation that his followers not respond in kind.45 In a letter dating from 1797, he explicitly referred to the burning of Tzavaat ha-Rivash and cited the question of divine immanence as the Gaon’s most fundamental critique of the Baal Shem Tov’s teachings.46 Rabbi Schneur Zalman then proposed a new resolution to the debate: “Let him clearly explain all his reservations against us regarding this belief . . . and he himself will append to it his signature, and I will follow after him . . . to respond to all his reservations, likewise written and signed in my own handwriting, and the two letters will be published together and sent to all the wise men of Israel who are near and far, so that they may offer their opinion in this matter . . . and by the majority we shall rule, and so there will be peace upon Israel, amen.”47

Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s proposal never came to fruition, but in the same year his magnum opus, Tanya, was published. Although this work had already been circulated widely in manuscript copies, one significant section was omitted from the first published edition, apparently to avoid further confrontation with the mitnagdim:

In the second part of Tanya, titled Shaar ha-Yichud veha-Emunah (lit., “The Gate of Unity and Faith”), Rabbi Schneur Zalman directly addressed the Gaon’s assertion that G‑d’s self is not present within the world, and that nothing more than divine superintendence (hashgachah) is exercised therein. This discussion exists in several manuscript editions, but first appeared in print in the authoritative Vilna edition of Tanya, published in 1900.48

If the two positions maintained by the Gaon are correctly understood, Rabbi Schneur Zalman argued, they are revealed to be mutually exclusive: it is logically incoherent to claim that the divine self is removed from the created realm, but yet has knowledge and jurisdiction over all created beings.49

In order to articulate his point, Rabbi Schneur Zalman invoked Maimonides, who explained that it would be wrong to conceive of divine knowledge in the same way we experience human knowledge. The human experience of knowledge is comprised of three utterly distinct components; 1) the subjective self that perceives (the knower); 2) the object that is perceived (the known); and 3) what the subject perceives of the object (the knowledge). But the essential unity of the divine self does not allow for multiple components of divine knowledge. It is logically incoherent to claim that the divine self is removed from the created realm, but yet has knowledge and jurisdiction over all created beings.We must conclude therefore, that all divine knowledge is actually self-knowledge: “He is the Knower, He is the Subject of Knowledge, and He is the Knowledge itself. All is one.”50

If divine knowledge is self-knowledge, reasons Rabbi Schneur Zalman, then divine superintendence of the created realm entails that the divine self is actually extended throughout that realm. This conclusion echoes the statement of Rabbi Avraham Cohen de Herrera (cited above) that G‑d is not only the external cause of all created things but “also passes through all of them, fills them all, and is all that they are.” In other words, the notion of divine providence is actually incompatible with the claim that the divine self is literally absent from creation.

The Maimonidean understanding of divine knowledge, explains Rabbi Schneur Zalman, reveals that those “who thought themselves clever” and interpreted the Arizal’s tzimtzum narrative literally “did not speak with understanding.” Since they themselves believe “that G‑d knows all the created beings in this lower world and exercises providence over them,” and “He knows all by knowing His self,” they too must admit that G‑d’s transcendent self is immanently present throughout all existence, for “His essence and His being and His knowledge are all one.” The literalist claim—that the divine self is removed from the created realm, and that divine superintendence is yet asserted therein All divine knowledge is actually self-knowledge: “He is the Knower, He is the Subject of Knowledge, and He is the Knowledge itself. All is one.”—is demonstrated to be logically untenable. The tzimtzum narrative must therefore be interpreted in terms of concealment rather than absence.

The very principle put forth by Rabbi Immanuel Ricchi, and later by the Vilna Gaon, to buttress their rejection of the non-literal interpretation of the tzimtzum narrative was used by Rabbi Schneur Zalman to reverse that rejection and uphold the non-literal interpretation.

The success of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s argument is best demonstrated by an examination of how Arizal’s narrative was understood by Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin, the Vilna Gaon’s foremost disciple. In his famous work of Jewish thought and ethics, Nefesh ha-Chaim, Rabbi Chaim wrote explicitly that “tzimtzum does not mean ‘departure’ and removal,’ but ‘hiddenness’ and ‘concealment.’” Rather than describing the “line” (kav) of divinity which is extended into the created realm as “an extremely limited stewardship,” as did the Gaon, Rabbi Chaim describes it as “a limited revelation . . . that arrives by way of ordered degree and many concealments [even] to the very lowest forces.” Arizal’s intention, he explained, was not that G‑d was literally removed from the created realm, but that “G‑d’s unified self, the divine essence that fills all worlds, is withdrawn (metzumtzam) and concealed from our grasp.”51

The interpretation advocated by Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin upholds the very position that his master and predecessor, the Vilna Gaon, Although the issue of divine immanence was laid to rest, a separate distinction regarding the import of tzimtzum yet remained outstanding. had censured the chassidim as heretics for asserting: that the divine self is imminently present even in the lowest of created realms, and that tzimtzum implies concealment rather than absence.52 Of course, Rabbi Chaim did not adopt the chassidic worldview and way of life in its entirety, and many differences yet remained between chassidim and mitnagdim. But, robbed of its ideological basis, the struggle against the chassidic movement lost much of its potency and power.

Although the issue of divine immanence was laid to rest, a separate distinction regarding the import of tzimtzum yet remained outstanding. Did the tzimtzum conceal the very essence of the divine self (atzmut ein sof), or only the manifestation of that essence (ohr ain sof)? If you pay close attention to the words of Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin cited above, it appears that he understood tzimtzum as a concealment of the divine essence itself. Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, however, taught that the essence itself is categorically beyond concealment.53 Due to its esoteric subtlety, this distinction was never cause for conflict, but it is by no means insignificant. This is an issue that penetrates to the very core of divine being, and uncovers the quintessential intimacy that lies at the epicenter of otherness.

With G‑d’s help, the question of how far the concealment of tzimtzum extended, along with its attendant consequences, will be addressed in a future article.

Join the Discussion