One sunny afternoon in 1986 found quite a large group of chassidim gathered outside Lubavitch World Headquarters, the building known as 770. On that day, there were more than the usual few that would come to bring their kids to receive coins from the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, to place in a charity box; for word had spread that the Rebbe would for the first time be using a new stretch Cadillac that had been purchased for his use.

The Rebbe would soon be leaving to visit the gravesite – the Ohel – of his predecessor and father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, in Cambria Heights, Queens, a half hour's drive from his office in 770.

In the back of their minds, many of them knew that they should not be there; the Rebbe would certainly rather that they utilize their time productively, studying Torah or doing good deeds. Some, in fact, did leave. But there still remained a sizable crowd.

At the age of eighty-four, the Rebbe could have used a new car. The seats in the old car, a 1977 model, were rubbed out, and the increased legroom – as well as some other amenities – in the new car would certainly make for a more comfortable ride.

A group of the Rebbe's aides had worked on purchasing a suitable car. The Rebbe's wife, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, of righteous memory, was also involved in choosing the car, and had herself selected the seats' fabric. The Rebbe was presumably aware that a new car was needed and that one was being purchased.

The Rebbe's premier ride in the car was supposed to be a quiet event, no one had anticipated that it would cause any raucous whatsoever; the Rebbe would simply start using the new vehicle, and hopefully it would make the ride easier. In fact, the car was supposed to have been brought very discreetly to the Rebbe’s home that morning, from where the Rebbe would be driven to 770. This would have prevented a spectacle at the car’s “inaugural ride.” Due to mechanical reasons, however, the car was not ready for delivery till later that morning.

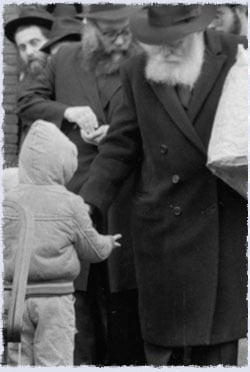

The Rebbe exited 770, distributing coins to the children to give to charity, as was his practice. It seems that the Rebbe noticed the larger than usual crowd. Reaching the curb, the Rebbe turned to his aide, Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, and asked, "Where is the car that we used yesterday?"

The new car was immediately driven away and the old car was brought. "Is this the car?" the Rebbe asked. When Rabbi Krinsky responded in the affirmative, the Rebbe entered the car and was driven to the Ohel. And the Rebbe continued to be driven in the old car.

The entire event lasted not more than five minutes.

(Rabbi Krinsky relates that after the Rebbetzin's passing the Rebbe requested that the new car that was purchased be given to one of the aides who assisted her in the home, so he should have a means for livelihood.)

Why Not a New Car?

To be constructive in life, sometimes it is necessary for us to break out of our nature. Chabad teachings contain many pages devoted to the subject of refraining from that which is extra, holding back from doing that which we really want to do—but don't really need.

You want to read that novel, you want to sleep in, you want to relish that delectable steak; when instead you take that time to do another a favor, crack open a Jewish book or call your mom to chat, you have done what is called iskafya.

Iskafya literally means "suppressing"; suppressing our personal desires in favor of focusing on a higher cause. It's an exercise in subjugating the body and its needs to the soul and matters of the spirit. It's about becoming more refined and spiritual.

After the Rebbe eschewed the comforts of a new car, Chabad thinkers, mentors and theorists found a new way to illustrate the concept of iskafya. It was the talk of the town. Was the new car an absolute necessity? Of course not!

Sometimes You Don't Need Iskafya...

The Rebbe, however, maintained otherwise.

During the course of a farbrengen (chassidic gathering) some two months later, the Rebbe touched on the topic of iskafya—in fact, he spoke of iskafya in reference to the purchase of a new car.

"At times," the Rebbe explained (freely translated and paraphrased here), "we desire a new car, with the rationale that the newer vehicle will help us arrive faster to our destinations—in our pursuit to do good deeds!"

The Rebbe said that we shouldn't use G‑d and holy endeavors to justify personal desires... Despite the supposedly lofty intentions, not purchasing a new car would constitute iskafya.

"There are those that purchased a new car," the Rebbe continued, alluding to the events of a few weeks beforehand. "They say that there is a need for the new car, for the seats [in the old one] are rubbed out, etc."

However, the Rebbe explained, to him a new car or an old one made no difference whatsoever. "I have no idea of the difference! I know that [the old] car was the agent for a lot of good missions in the past and it could continue doing so in the future..."

The concept of iskafya, therefore, does not apply here. By way of analogy the Rebbe explained that if someone likes red potatoes and when someone brings him white potatoes he does not eat it—no one will claim that he is doing iskafya.

"Iskafya is when you know that the amount of charity you are giving is a lot less than you could give, and you do not want to give any more, but you give anyway..."

Why?

So despite the punditry that abounded, it wasn't about iskafya. So why indeed did the Rebbe refuse the new car?

No one ever asked the Rebbe this question, so all answers are merely speculation. Maybe it was the spectacle and crowd that was present waiting for the Rebbe's reaction? Maybe the Rebbe felt that a big deal was being made out of something that didn't warrant such attention?

We will never know; we did, however, end up gaining a lesson about the meaning of iskafaya. Let's take it to heart.

Dedicated in memory of Rabbi Bentzion Shafran, of blessed memory. Rabbi Shafran was a true soldier in the Rebbe's army and dedicated his life to assisting Jewish soldiers and prisoners.

Special thanks to Rabbis Yehuda Krinsky, Chaim Shaul Brook and Michoel Seligson for their assistance in researching this article.