Had the Rambam written no other work but the Commentary on the Mishnah, it would have been sufficient to immortalize him among the Jewish people. But he had no sooner completed this work than he embarked on his next and even more ambitious project, the codification of Jewish law.

Some years earlier Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi (known as the "Rif") took the first major step in codifying the laws of the Talmud. It was beyond the ability of the average person, indeed of anyone except the greatest scholar, to determine directly from the Talmud with its numerous opinions and diverse views, the final ruling on Jewish law on any given matter. Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi gleaned the legal passages and authoritative opinions of the Talmud, deleting the intricate discussion of the Amoraim and all non legal material, and organized them in more or less the same order and form, quoting them in the very words as they were presented in the Talmud, and, where necessary, indicating the law. This was, indeed, a monumental achievement in determining the final, definitive Jewish law. His method of codification, however, followed the arrangement of the Talmud, not a topical system, where all laws of the same subject are grouped under the same heading. As the years passed, the pressing need for a more systematically arranged, clear-cut, practical code was increasingly felt. It was the crowning accomplishment of Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon to present the first comprehensive, all encompassing, topically arranged code of Jewish law, distinguished by matchless clarity and lucidity. In the words of the Rambam himself, in his introduction to Mishneh Torah:

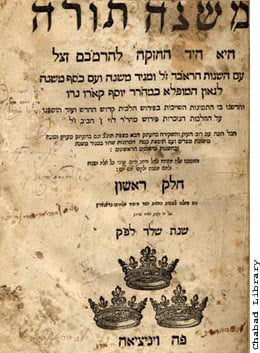

...At this time, the sufferings of our people have increased. The pressing need of the moment supersedes every other consideration. The wisdom of the wise has vanished, and the wisdom of our learned men is concealed. Hence, the commentaries, compilations of laws and Response of the Gaonim, which they thought were easy to understand, have in our times become difficult to understand, and there are only a few individuals who are able to comprehend them properly... For this reason, I, Moshe ben Maimon, the Sephardi, have girded my loins and relying on the help of the Almighty, blessed be He, have thoroughly studied all their works and decided to compile the results derived from them as to what is prohibited and what is permitted, what is clean and what is unclean, and all the other laws of the Torah, all in clear language and concise style, so that the entire oral Torah will be systematically arranged for all. [I shall not quote] the questions and answers or the differences of opinion discussed... but only the laws themselves in a clear and succinct manner, in accordance with the conclusions derived from all these treatises and compilations existing since the time of Rabbi Yehudah HaNassi until the present day – so that all the laws shall be accessible to young and old, whether they are Biblical precepts or enactments by the sages or Prophets. In short, [my purpose in composing this code is] that no man shall have any need to resort to any other book on any matter of Jewish law, but that this compendium contain the entire Oral Law, including the ordinances, customs and decrees instituted from the time of Moses to the redaction of the Talmud, and as expounded for us by the Gaonim in all their works composed by them since the completion of the Talmud. Therefore, I called this work Mishneh Torah (Second Law to the Torah), for a man should first read the Written Torah and then read this code and he will know from it the entire Oral Law without the need of reading any other book between them.

The Book of the Commandments

Before commencing the monumental task of codifying the whole range of Jewish law material contained in the Biblical, Talmudic and Gaonic literature, the Rambam composed another work on Jewish law, called Sefer HaMitzvot – The Book of the Commandments. It is a sort of introduction to the Mishneh Torah, but is also a valuable work in its own right and is the second of his three major works on Jewish law, the other two being his Mishnaic Commentary and the Mishneh Torah.

The main objective of Sefer HaMitzvot is to enumerate the six hundred thirteen precepts contained in the Torah. The Sages of the Talmud speak of 613 commandments, i.e., the six hundred thirteen Biblical commandments. These are subdivided into two hundred forty-eight positive precepts (mitzvot aseh) and three hundred sixty-five negative or prohibitory precepts (lo ta'aseh or. lav). A simple, superficial counting of the Biblical laws, however, yields a substantially larger number than six hundred thirteen. Nowhere in the Talmud is there a detailed enumeration given of these injunctions and prohibitions nor an explicit formulation of the principles and rules on the basis of which Biblical laws should be counted.

Each one of the six -hundred thirteen precepts serves either to inculcate proper attitudes or to remove some erroneous conceptions, to establish just legislation or to eliminate iniquity, to imbue one with exemplary virtues or to deter one from evil dispositions.

Moreh Nevuchim 3:31

Join the Discussion