We’ve all experienced the frustration of following an instruction manual to set up electronic equipment or assemble a dresser. At some point, well past when the manual insists we should be enjoying the stereo or armoire, we scream in frustration, “Why do they make it so complicated?!”

Imagine you had the author of that pamphlet with you. After you are done wringing his neck, he could easily explain to you how simple the directions are. And he would question why intelligent people are reduced to tears when faced with a simple task. The simple answer is that successfully describing something without the benefit of interaction with your audience, without nods of understanding or looks of bewilderment, is a near-impossible task.

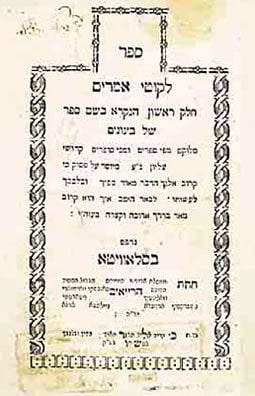

Now imagine that you are not trying to teach clumsy parents how to assemble a toy—you are instead trying to instruct all of the Jewish people, for all time, in every area of their lives. Over 200 years ago, in a small town in Eastern Europe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, founder of the Chabad stream of chassidic thought, set out to do just that.

He boldly declares that one who examines this book closely will find the answer to all his spiritual queriesIn the introduction to the Tanya, his great work, he boldly declares that one who examines this book closely will find the answer to all his spiritual queries. A bold claim and daunting task, to be sure.

By this time, chassidic teachings had achieved renown and popular acceptance and respect. Yet its teachings had always been coupled with personal guidance; the sheer force of presence of a Rebbe was an integral, indispensable component of the teachings. And now Rabbi Schneur Zalman, also known as the “Alter Rebbe,” was making these delicate, highly personal ideas available to anyone and everyone, his life’s work and the richness of his experiences all crammed into a book available to the unlettered and inexperienced.

And he succeeded. A fact that can be attested to by the tens of thousands who study the Tanya to this very day, and find the answers to all their twenty-first-century issues in its timeless pages.

But how did he do it? How could the Alter Rebbe be so confident that everyone would be able to find individual guidance in this “one-size-fits-all” writing?

The full message of Tanya is beyond the scope of this article. I wish to focus on one phrase in Tanya which, I think, captures the substantive difference between the Alter Rebbe’s approach and that of all those who preceded and followed him, each seeking to capture the Torah’s instruction for life—and which perhaps explains how he managed this incredible feat.

In Tanya, the Alter Rebbe gets down to the tough question, the answer to which the book’s title page describes as its mission to provide: the meaning of the verse (Deut. 30:14), “Behold, this thing [all of the Torah and its commandments] is very near to you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may do it.”

The Tanya begins its analysis in classic Jewish academic form; the veracity of this verse is challenged, and potential responses are offered.

And then, in Chapter 17, the Alter Rebbe—in three words—sums up the crux of the problem. The Hebrew words are נגד החוש שלנו—my best attempt at translation is “our experience suggests otherwise.”

The Rebbe, a person utterly devoid of attraction to anything but holiness, recognizes that “our experience suggests otherwise” . . .I find that statement remarkably compassionate and real. The Alter Rebbe, a holy person utterly devoid of attraction to anything but holiness, recognizes that “our experience suggests otherwise”—that the student struggling with his relationship with G‑d, whether in eighteenth-century Russia or at his computer in materialist America, might not feel connected with G‑d. He feels lost despite the insistence of his parents, teachers, and rabbis that he should feel spiritually connected. Traditional Jewish teaching has hammered away at that student, quoting from Scripture, “proving” G‑d’s existence and immediacy. The Alter Rebbe, taking a revolutionary and very human track, acknowledges the very human experience of emptiness, that some just don’t sense G‑d in their lives.

What happens to the high-schooler who sits in class day after endless day watching her classmates “get it,” while she stares at the ceiling, befuddled, and even worse, disgusted with herself because she doesn’t see/feel/understand what her classmates do? It’s more than poor grades—it’s the forfeiture of self. Her self-image is “I must be broken,” because I can’t do what everyone else does.

Into this frustrated life steps the Alter Rebbe and shows a side often absent in academics and preachy rabbis. He empathizes. He says, “I understand. All the lofty discussion of G‑dliness and Torah, all the evidence of Infinity and lectures of meaning is נגד החוש שלנו, contrary to our experience.” Our experience. Yes, even the Alter Rebbe himself senses the loneliness, feels the frustration. I am with you, he says. Together we will walk this path.

This is where the Alter Rebbe’s teachings stand out, and it may in fact be why he makes the bold claim that he is writing a book for everyone’s struggle: because he speaks from within—he is willing to replace the standard academic process, of validating a theory through quotes and platitudes, with genuine human experience. The Alter Rebbe gets “down and dirty” with real human fallibility, the profound human tragedy of feeling disconnected.

Into this sadness, the Alter Rebbe offers guidance—a light for those who thought that they were broken, that they were the problem. They had already exhausted all the “timeouts,” special tracks, and modified school programs. The experts concluded that they were just hopelessly lost.

The Alter Rebbe understands. He includes himself in the experience, and then he shows us the way he got out, and invites us to come along.

There are Tanya classes on this website and in many Chabad centers. Join in—you belong.

Join the Discussion